Yahya Khan

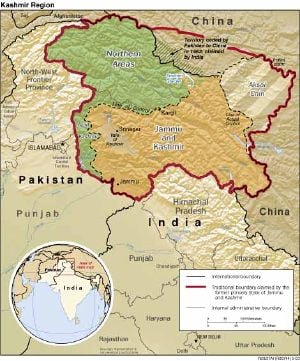

Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan (February 4, 1917 – August 10, 1980) was the President of Pakistan from 1969 to 1971, following the resignation of Ayub Khan who has promoted him rapidly through the ranks of the army and hand-picked him as his successor. During World War II, he served as a junior officer in Africa, Italy, and Iraq. He was interned in and escaped from a prisoner-of-war camp. By 34 he was the army's youngest brigadier commanding troops along the Line-of-Control in Kashmir. By 40, he was Pakistan's youngest general. He was already Ayub Khan's most loyal lieutenant, and was promoted over seven more senior generals, in 1966, to the army's top post, again the youngest officer to occupy this position. His presidency was faced with the challenge of trying to unite a divided country, with the East rebelling against exploitation by the West. Unable to resolve the dispute politically, largely due to the intransigence of the political leaders on both sides, he waged war on his own people, however reluctantly. Ziring has said that he did not "want his troops slaughtering unarmed Pakistani civilians" in the East, but "did nothing to stop it."[1] When Bangladesh became independent in 1971, he became the last President of a united Pakistan.

He shared Ayub Khan's view that Pakistan's politicians had failed to maintain national unity or to resolve the ongoing dispute with India over Kashmir, believing that the military had a mission to save the nation. To his credit, he delivered elections in 1970 but when Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's East Pakistani Awami League won the largest number of seats, the result was quashed. Ironically, that was considered to have been the first free and fair election in Pakistan's history.[2] However, his viciousness in trying to suppress the East's aspirations for autonomy, which resulted in the birth of Bangladesh, cancels any credit he may have deserved for holding elections. In the end, he did nothing to nurture democracy. As he told foreign journalists in 1971, "The people did not bring me to power. I came myself," suggesting a certain indifference about political legitimacy at least in terms of a democratic mandate.[3] Although democracy was restored following his rule, it only lasted five years before, emboldened by the Ayub-Yahya legacy of military governance in Pakistan, another military dictator seized power.

Early life

Yahya Khan was born in Chakwal in 1917, to an ethnic Shi'a Muslim Qizilbash family of Persian descent who could trace their military links to the time of Nader Shah. He was, however, culturally Pashtun.

Nader Shah was killed in a revolution and some members of his family escaped from Iran to what later became the Northern Pakistan area. The story is that after the Qizilbash family escaped bare handed, the family jewels and the small amount of treasure they carried were enough to buy them villages and maintain a royal life style. The Qizilbash family entered the military profession, producing many high level government officials and generals over the years.

He attended Punjab University and the Indian Military Academy, Dehra Dun, where he finished first in his class. He was commissioned on July 15, 1939, joining the British Army. In World War II he was a junior officer in the 4th Infantry Division (India). He served in Iraq, Italy, and North Africa. He saw action in North Africa, where he was captured by the Axis Forces in June 1942, and interned in a prisoner of war camp in Italy, from where he escaped on the third attempt.

Career before becoming Chief of Army Staff (COAS)

In 1947, he was instrumental in not letting the Indian officers shift books from the famous library of the British Indian Staff College at Quetta, where Yahya was posted as the only Muslim instructor at the time of partition of India. He then transferred to the Pakistani army.

Yahya became a brigadier at the age of 34 and commanded the 106 Infantry Brigade, which was deployed on the ceasefire line in Kashmir (the Line of Control) in 1951-52. Later Yahya, as Deputy Chief of General Staff, was selected to head the army’s planning board set up by Ayub to modernize the Pakistan Army in 1954-57. Yahya also performed the duties of Chief of General Staff from 1958 to 1962, from where he went on to command an infantry division from 1962 to 1965.

During the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, he commanded an infantry division. Immediately after the 1965 war, Major General Yahya Khan who had commanded the 7th Division in Operation Grand Slam was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant General, appointed Deputy Army Commander in Chief and Commander in Chief designate in March 1966. At every point as he rose through the ranks, he was the youngest officer to achieve each rank.

As Chief of Army Staff (COAS)

Yahya energetically started reorganizing the Pakistan Army in 1965. The post 1965 situation saw major organizational as well as technical changes in the Pakistan Army. Till 1965 it was thought that divisions could function effectively while getting orders directly from the army’s GHQ. This idea failed miserably in the 1965 war and the need to have intermediate corps headquarters in between the GHQ and the fighting combat divisions was recognized as a foremost operational necessity after the 1965 war. In 1965 war the Pakistan Army had only one corps headquarter (such as the 1st Corps Headquarters).

Soon after the war had started, the U.S. had imposed an embargo on military aid on both India and Pakistan. This embargo did not affect the Indian Army but produced major changes in the Pakistan Army’s technical composition. U.S. Secretary of State Dean Rusk well summed it up when he said, "Well if you are going to fight, go ahead and fight, but we’re not going to pay for it."[4]

Pakistan now turned to China for military aid and the Chinese tank T-59 started replacing the U.S. M-47/48 tanks as the Pakistan Army’s MBT (Main Battle Tank) from 1966. Eighty tanks, the first batch of T-59s, a low-grade version of the Russian T-54/55 series were delivered to Pakistan in 1965-66. The first batch was displayed in the Joint Services Day Parade on March 23, 1966. The 1965 War had proved that Pakistan Army’s tank infantry ratio was lopsided and more infantry was required. Three more infantry divisions (9, 16, and 17 Divisions) largely equipped with Chinese equipment and popularly referred to by the rank and file as "The China Divisions" were raised by the beginning of 1968. Two more corps headquarters, such as 2nd Corps Headquarters (Jhelum-Ravi Corridor) and 4th Corps Headquarters (Ravi-Sutlej Corridor) were raised.

In the 1965 War, India had not attacked East Pakistan which was defended by a weak two-infantry brigade division (14 Division) without any tank support. Yahya correctly appreciated that the geographical as well as operational situation demanded an entirely independent command set up in East Pakistan. 14 Division’s infantry strength was increased and a new tank regiment was raised and stationed in East Pakistan. A new Corps Headquarters was raised in East Pakistan and was designated as Headquarters Eastern Command. It was realized by the Pakistani GHQ that the next war would be different and East Pakistan badly required a new command set up.

President of Pakistan

Ayub Khan was President of Pakistan for most of the 1960s, but by the end of the decade, popular resentment had boiled over against him. Pakistan had fallen into a state of disarray, and he handed over power to Yahya Khan, who immediately imposed martial law. Once Ayub handed over power to Yahya Khan on March 25, 1969, Yahya inherited a two-decade constitutional problem of inter-provincial ethnic rivalry between the Punjabi-Pashtun-Mohajir dominated West Pakistan province and the ethnically Bengali Muslim East Pakistan province. In addition, Yahya also inherited an 11 year old problem of transforming an essentially one man ruled country to a democratic country, which was the ideological basis of the anti-Ayub movement of 1968-69. Herein lies the key to Yahya’s dilemma. As an Army Chief, Yahya had all the capabilities, qualifications, and potential. But Yahya inherited an extremely complex problem and was forced to perform the multiple roles of caretaker head of the country, drafter of a provisional constitution, resolving the One Unit question, satisfying the frustrations and the sense of exploitation and discrimination successively created in the East Wing by a series of government policies since 1948. All these were complex problems and the seeds of Pakistan Army’s defeat and humiliation in December 1971, lay in the fact that Yahya Khan blundered unwittingly into the thankless task of fixing the problems of Pakistan’s political and administrative system which had been accumulating for 20 years.

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, later President and Prime Minister of Pakistan. His daughter, Benazir Bhutto would also serve as Prime Minister, perpetuating his political legacy.

Plan to preserve unity

Yahya Khan attempted to solve Pakistan’s constitutional and inter-provincial/regional rivalry problems once he took over power from Ayub Khan in March 1969. The tragedy of the whole affair was the fact that all actions that Yahya took, although correct in principle, were too late in timing, and served only to further intensify the political polarization between the East and West wings.

- He restored the pre-1955 provinces of West Pakistan

- Promised free direct, one man one vote, fair elections on adult franchise, a basic human right which had been denied to the Pakistani people since the pre-independence of 1946 elections

Yahya also made an attempt to accommodate the East Pakistanis by abolishing the principle of parity, thereby hoping that greater share in the assembly would redress their wounded ethnic regional pride and ensure the integrity of Pakistan. Instead of satisfying the Bengalis it intensified their separatism, since they felt that the west wing had politically suppressed them since 1958. Thus, the rise of anti-West Wing sentiment in the East Wing.

The last days of united Pakistan

Yahya announced in his broadcast to the nation on July 28, 1969, his firm intention to redress Bengali grievances, the first major step in this direction being, the doubling of Bengali quota in the defense services. It may be noted that at this time there were just Seven infantry battalions of the East Pakistanis. Yahya’s announcement, although made with the noblest and most generous intentions in mind, was late by about twenty years. Yahya’s intention to raise more pure Bengali battalions was opposed by Major General Khadim Hussain Raja, the General Officer Commanding 14 Division in East Pakistan suggesting that the Bengalis were "too meek to ever challenge the martial Punjabi or Pathan Muslim."[5]

Within a year, he had set up a framework for elections that were held in December of 1970. The results of the elections saw Pakistan split into its Eastern and Western halves. In East Pakistan, the Awami League (led by Mujibur Rahman) held almost all of the seats, but none in West Pakistan. In West Pakistan, the Pakistan Peoples Party (led by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto) won the lion's share of the seats, but none in East Pakistan. Though AL had 162 seats in the National Assembly against 88 of PPP, this led to a situation where one of the leaders of the two parties would have to give up power and allow the other to be Prime Minister of Pakistan. The situation also increased agitation, especially in East Pakistan as it became apparent that Sheikh Mujib was being denied his legitimate claim to be the Prime Minister of Pakistan. Bhutto would not agree to Mujib forming a government because he feared that Mujib's demand that the East become autonomous would result in the dismemberment of Pakistan, while Mujib would not accept Bhutto's offer of a joint Prime Ministership. To his credit, Yahya Khan wanted Mujib to form a government and was frustrated by the political impasse that made this possible, possibly confirming his jaundiced opinion of political leaders.

Yahya Khan could not reach a compromise, and instead cracked down on the political agitation in East Pakistan with a massive campaign of repression named by "Operation Searchlight" which began on March 25, 1971, targeting, among others, Muslims, Hindus, Bengali intellectuals, students, and political activists. The President ordered the army to restore order “by whatever means were necessary."[6] Three million people in the east Pakistan were killed in the next few months along with an another 0.4 million women were raped by the Pakistan army officials within the cantonment area. Khan also arrested Sheikh Mujibur Rahman upon Bhutto's insistence and appointed Brigadier Rahimuddin Khan (later General) to preside over a special tribunal dealing with Mujib's case. Rahimuddin sentenced Mujib to death but Yahya put the verdict into abeyance, imprisoning him instead. Yahya's crackdown, however, led to a civil war within Pakistan, and eventually drew India into what would extend into the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971. The end result was the establishment of Bangladesh as an independent republic, and this was to lead Khan to step down. After Pakistan was defeated in 1971, most of the blame was heaped on Yahya. Yahya would actually have "preferred a political solution" but faced with intransigence all around him played the military card instead; "and bears major responsibility for what happened," that is, the war in the East. He had charged Mujib with treason and blamed the Awami League for causing disorder."[7]

China and the U.S.

Before he was forced to resign, President Khan helped to establish the communication channel between the United States and the People's Republic of China, which would be used to set up the Nixon trip in 1972.[8] In 1969, Richard Nixon visited him in Pakistan. Nixon, it is said, regarded him highly and personally asked him to pass on a message to the Chinese leader, Zhou En-lai, with whom Yahya had developed a "good rapport" concerning "a possible U.S. opening to China." Secret negotiations over the next two years led to the announcement, by Kissinger "from Beijing in 1971 that the United States and the People's Republic were beginning a process of normalizing relations."[9] The U.S. was perceived as shifting away from India towards Pakistan at this period, although Pakistan was already receiving considerable aid from the U.S. because of its anti-Soviet stance, which would subsequently increase after the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan in 1978.

Fall from power

Later overwhelming public anger over Pakistan's humiliating defeat by India, a genocide in east Pakistan which killed over 3 million people and the division of Pakistan into two parts boiled into street demonstrations throughout Pakistan, rumors of an impending coup d'état by younger army officers against the government of President Mohammed Agha Yahya Khan swept the country. Yahya became the highest-ranking casualty of the war: to forestall further unrest, on December 20, 1971, he hastily surrendered his powers to Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, age 43, the ambitious leader of West Pakistan's powerful People's Party.

On the same day that Zulfikar Ali Bhutto released Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and saw him off to London, Pakistan President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, in a supreme irony, ordered the house arrest of his predecessor, Agha Mohammed Yahya Khan, the man who imprisoned Mujib in the first place. Both actions produced headlines round the world. But in Pakistan they were almost overshadowed by what Bhutto grandly called "the first steps toward an economic and social revolution." Shortly after his release, Yahya suffered a stroke from which he never fully recovered.

Death

Yahya Khan died in August 1980, in Rawalpindi. He was survived by one son, Ali Yahya and by one daughter, Yasmeen Khan.

Legacy

While Yahya Khan's military rule, itself an extension of Ayub Khan's, was replaced by civilian rule under Bhutto, this did not last long. By 1977, General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq had intervened once again. Like Ayub, he ruled for a decade promising but never delivering elections. Bhutto was executed. Yahya Khan may actually have had more sympathy towards democracy than his predecessor, given that he did order the elections of 1970. Former Major Amin comments that Yayha was professionally competent, naturally authoritarian, a man of few words, adding that he also had a fondness for alcohol.[5]

A journalist writing in 1971 described him as; ruling "with impatience, ill-disguised contempt for bungling civilians, and a cultivated air of resentment about having let himself get involved in the whole messy business in the first place."[3] However, the way in which he crushed unrest in what became Bangladesh over the stalemate caused by the election result did nothing to further democracy, and detracts from the any credit he may be due for holding the election. Instead, he gave those who succeeded him in leading the military a precedent to intervene in government in the name of fighting corruption or maintaining national unity and stability. This precedent would influence future events in Bangladesh as well as in Pakistan. In Bangladesh, the very man who supervised the 1970 election as Yahya Khan's Chief Election Commissioner, Justice Abdus Sattar would be overthrown in 1982 by a General arguing that the politicians were failing to rule efficiently, while the army was better equipped to build the new nation, then just a decade old.

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: ?? |

Chief of General Staff 1957 - 1962 |

Succeeded by: Major General Sher Bahadur |

| Preceded by: General Musa Khan |

Commander in Chief of the Pakistan Army 1966–1971 |

Succeeded by: Lt General Gul Hassan Khan |

Notes

- ↑ Ziring (1997), 354.

- ↑ Isambard Wilkinson, Pakistan elections "rigged for Musharraf's allies," The Telegraph.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Time,Good Soldier Yahya Khan. Retrieved August 11, 2008.

- ↑ Dennis Kux, India and the United States: Estranged Democracies (Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, 1992, ISBN 9789992335482), 239.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Humayun Agha Amin, The Pakistan Army: From 1965 to 1971, Defence Journal. Retrieved August 11, 2008.

- ↑ Sathasivam (2005), 82.

- ↑ Ziring (1997), 304.

- ↑ William Burr, September 1970-July 1971 National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 66, National Security Archive. Retrieved August 11, 2008.

- ↑ Sathasivam (2005), 81.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bhutto, Benazir. 2008. Reconciliation: Islam, Democracy, and the West. New York: Harper. ISBN 9780061567582.

- Burki, H. K. 2004. Tales of a Sorry Dominion: Pakistan 1947-2003. Islamabad, PK: Alhamra. ISBN 9789695161425.

- Einfeld, Jann. 2004. Pakistan. San Diego, CA: Greenhaven Press. ISBN 9780737720433.

- Khan, Hamid. 2001. Constitutional and Political History of Pakistan. Karachi, PK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195793413.

- Sathasivam, Kanishkan. 2005. Uneasy Neighbors: India, Pakistan and US Foreign Relations. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate. ISBN 9780754637622.

- Ziring, Lawrence. 1997 Pakistan in the Twentieth Century: A Political History. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195778152.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.