Yongzheng Emperor

The Yongzheng Emperor ( 雍正 born Yinzhen 胤禛) (December 13, 1678 - October 8, 1735) was the fourth emperor of the Manchu Qing Dynasty, and the third Qing emperor to rule over China, from 1722 to 1735. Historical information about the Yonzheng Emperor includes extensive debates about his ascension to the throne. His father, the Kangxi Emperor left fourteen sons and no designated heir; many accounts suggest Yongzheng usurped the throne from his younger brother Yinti, and portray him as a despot.

Though he is less well-known than the Kangxi Emperor and his son, the Qianlong Emperor( 乾隆), the Yongzheng Emperor’s thirteen-year rule was efficient and vigorous. During his reign, the Qing administration was centralized and reforms were instituted which ensured the Kangqian Period of Harmony, a period of continued development in China. He disliked corruption and punished officials severely when they were found guilty of the offense. Yongzheng reformed the fiscal administration and strengthened the authority of the throne by uniting the leadership of the Eight Banners (elite Manchu military divisions) under the emperor. The Qing government encouraged settlement in the southwest, appointed Han Chinese officials to important posts, and used military force to secure China’s borders.

Background

The early Qing (Ch'ing) dynasty

The Manchu Qing ( Ch'ing) came to power after defeating the Chinese Ming dynasty and taking Beijing in 1644. During the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the Qing enacted policies to win the adherence of the Chinese officials and scholars. The civil service examination system and the Confucian curriculum were reinstated. Qing (Ch'ing) emperors learned Chinese, and addressed their subjects using Confucian rhetoric, as their predecessors had. They also continued the Ming practice of adopting era names for the rule of each emperor. Initially, important government positions were filled by Manchu and members of the Eight Banners, but gradually large numbers of Han Chinese officials were given power and authority within the Manchu administration.

The first Qing emperor, Shunzhi Emperor (Fu-lin ,reign name, Shun-chih), was put on the throne at the age of five and controlled by his uncle and regent, Dorgon, until Dorgon died in 1650. During the reign of his successor, the Kangxi Emperor (K'ang-hsi emperor; reigned 1661–1722), the last phase of the military conquest of China was completed, and the Inner Asian borders were strengthened against the Mongols.

The Prince Yong

The Yongzhen Emperor was the fourth son of the Kangxi Emperor to survive into adulthood, and the eldest son by Empress Xiaogong (孝恭皇后), a lady of the Manchu Uya clan who was then known as "De-fei." Kangxi knew it would be a mistake to raise his children in isolation in the palace, and therefore exposed his sons, including Yinzhen, to the outside world, and arranged a strict system of education for them. Yongzheng went with Kangxi on several inspection trips around the Beijing area, as well as one trip further south. He was the honorary leader of the Plain Red Banner during Kangxi's second battle against Mongol Khan Gordhun. Yinzhen was made a beile (貝勒, "lord") in 1698, and then successively raised to the position of second-class prince in 1689.

In 1704, there was unprecedented flooding of the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers, severely damaging the economy and robbing the people in these areas of their livelihood. Yongzheng was sent out as an envoy of the Emperor with the 13th Imperial Prince Yinxiang ( the Prince Yi 怡親王胤祥) to organize relief efforts in southern China. The Imperial Treasury, having been drained by unpaid loans to many officials and nobles, did not have sufficient funds to deal with the flooding; Yongzheng had the added responsibility of securing relief funds from the wealthy southern tycoons. These efforts ensured that funds were distributed properly and people would not starve. He was given the peerage title of a first-class Prince, the Prince Yong (雍親王) in 1709.

Disputed Succession to the Throne

In 1712 the Kangxi Emperor removed the second of his twenty surviving sons, Yinreng ( 胤礽), the heir apparent to the imperial throne of China, as his successor, and did not designate another one. This led to further fragmentation in the court, which had long been divided among supporters of Yinzhi ( Aisin-Gioro 胤祉) , Yinzhen, Yinsi ( the Prince Lian 廉亲王胤禩), and Yinti (the Prince Xun 恂郡王胤禵), the 3rd, 4th, 8th, and 14th Imperial Princes, respectively. Of the princes, Yinsi had the most support from the mandarins, though often for reasons of personal gain. Prior to this, Yinzhen had been a supporter of the Crown prince. By the time the old Emperor died in December 1722, the field of contenders had narrowed to three Princes, Yinzhi, Yinti, and Yinzhen; Yinsi had pledged his support to the 14th prince Yinti, his brother by the same mother.

At the time of the Kangxi Emperor's death, Yinti, as Border Pacification General-in-Chief (撫遠大將軍), was away at the war front in the northwest. Some historians say this had been arranged in order to train the next Emperor in military affairs; others maintain that it was to ensure a peaceful succession for Yinzhen. It was Yongzheng who had nominated Yinti for the post, and not Yinti's supporter Yinsi. The posting of Yinti at the frontier was regarded as an indication of Kangxi's choice of successor, since the position of Crown Prince had been vacant for seven years.

The official record states that on December 20, 1722, the ailing Kangxi Emperor called to his bedside seven of his sons and the General Commandant of the Peking Gendarmerie, Longkodo (隆科多), an eminent Chinese official at court, who read out the will declaring that Yinzhen should succeed him on the imperial throne. Some evidence suggests that Yinzhen had already made contact with Longkodo months before the will was read, in order to make preparations for succession by military means, though in their official capacities the two would have encountered each other frequently. According to folklore, Yongzheng changed Kangxi's will by adding strokes and modifying characters. The most famous story was that Yongzheng changed “fourteen” (十四) to “four” (于四), others say it was “fourteen” to “fourth” (第四). Yinti was the fourteenth son and Yinxzhen the fourth son of the Kangxi emperor. Though this folklore has been widely circulated, there is little evidence to support the theory. The character "于" was not widely used during the Qing Dynasty; on official documents, "於" was used. According to Qing tradition, the will would have been written in both Manchu and Chinese, and Manchu writing would have been impossible to modify. Furthermore, princes in the Qing Dynasty were referred to as the Emperor's son, in the order in which they were born (such as "The Emperor's Fourth Son" Chinese: 皇四子). Therefore, the theory that Yinzhen changed the will in order to ascend to the throne has little substance.

Another theory suggests that Yinzhen forged a new will. The Manchu version has been lost, and the existing will in Chinese that is preserved in the Chinese Historical Museum was only issued two days after Kangxi's death.

According to Confucian ideals, the manner in which a ruler ascended the throne was important to the legitimacy of his rule, and it is possible that Yongzheng’s political enemies deliberately tried to discredit him by spreading rumors that he usurped the throne.

Yongzheng’s first official act as Emperor was to release his long-time ally, the 13th prince, Yinxiang (Prince Yi; 怡親王胤祥), who had been imprisoned by the Kangxi Emperor at the same time as the Crown Prince. Some sources indicate that Yinxiang, the most military of the princes, then assembled a special task force of Beijing soldiers from the Fengtai command to seize immediate control of the Forbidden City and surrounding areas, and prevent any usurpation by Yinsi's allies. Yongzheng's personal account stated that Yinsi was emotionally unstable and deeply saddened over his father's death, and knew it would be a burden "much too heavy" for himself if he were to succeed the throne. In addition, after the will was read, Yinzhen wrote that the officials (Premier Zhang Tingyu and Longkedo, Yinzhi (胤禔, the eldest son), and Prince Cheng led the other Princes in the ceremonial “Three-Kneels and Nine-Salutes” to the Emperor. On the next day, Yongzheng issued an edict summoning Yinti, who was his brother from the same mother, back from Qinghai, and bestowing upon their mother the title of Holy Mother Empress Dowager on the day Yinti arrived at the funeral.

Reign over China

In December 1722, after succeeding to the throne, Yinzhen took the era name of Yongzheng (雍正, era of Harmonious Justice), effective 1723, from his peerage title Yong, meaning "harmonious;" and zheng, a term for "just" or "correct." Immediately after succeeding the throne, Yongzheng chose his new governing council. It consisted of the 8th prince Yinsi (廉亲王胤禩); the 13th prince Yinxiang (怡親王胤祥); Zhang Tingyu (张廷玉), was a Han Chinese politician; Ma Qi; and Longkodo (隆科多). Yinsi was given the title of Prince Lian, and Yinxiang was given the title of Prince Yi, both holding the highest positions in the government.

Continued battle against the princes

Since the nature of his succession to the throne was unclear and clouded by suspicion, Yongzheng regarded all his surviving brothers as a threat. Two had been imprisoned by Kangxi himself; Yinzhi, the eldest, continued under house arrest, and Yinreng, the former Crown Prince, died two years into Yongzheng’s reign. Yongzheng’s greatest challenge was to separate Yinsi's party (consisting of Yinsi and the 9th and 10th princes, and their minions), and isolate Yinti to undermine their power. Yinsi, who nominally held the position of President of the Feudatory Affairs Office, the title Prince Lian, and later the office of Prime Minister, was kept under close watch by Yongzheng. Under the pretext of a military command, Yintang was sent to Qinghai, the territory of Yongzheng's trusted protégé Nian Gengyao. Yin'e, the 10th Prince, was stripped of all his titles in May 1724, and sent north to the Shunyi area. The 14th Prince Yinti, his brother born from the same mother, was placed under house arrest at the Imperial Tombs, under the pretext of watching over their parents' tombs.

Partisan politics increased during the first few years of Yongzheng's reign. Yinsi attempted to use his position to manipulate Yongzheng into making wrong decisions, while appearing to support him. Yinsi and Yintang, both of whom supported Yinti’s claim to the throne, were also stripped of their titles, languished in prison and died in 1727.

After he became Emperor, Yongzheng censored the historical records documenting his accession and also suppressed other writings he deemed inimical to his regime, particularly those with an anti-Manchu bias. Foremost among these writers was Zeng Jing, a failed degree candidate heavily influenced by the seventeenth-century scholar Lü Liuliang. In October 1728, he attempted to incite Yue Zhongqi, Governor General of Shaanxi-Sichuan, to rebellion by composing a long denunciation against Yongzheng, accusing him of the murder of the Kangxi Emperor and the killing of his brothers. Highly concerned about the implications of the case, Yongzheng had Zeng Jing brought to Beijing for trial.

Nian and Long

Nian Gengyao (年羹尧, a Chinese military commander) was a supporter of Yongzheng long before he succeeded the throne. In 1722, when Yongzheng summoned his brother Yinti back from the northeast, he appointed Nian to fill the position. The situation in Xinjiang at the time was still precarious, and a strong general was needed in the area. After he succeeded in several military conquests, however, Nian Gengyao's desire for power increased, until he sought to make himself equal to Yongzheng himself. Yongzheng issued an Imperial Edict demoting Nian to general of the Hangzhou Commandery. When Nian’s ambitions did not change, he given an ultimatum, after which he committed suicide by poison in 1726. Longkodo, who was commander of Beijing's armies at the time of Yongzheng's succession, fell into disgrace in 1728, and died under house arrest.

Precedents and reforms

Yongzheng is recognized for establishing strict autocratic rule and carrying out administrative reforms during his reign. He disliked corruption and punished officials severely when they were found guilty of the offense. In 1729, he issued an edict prohibiting the smoking of madak, a blend of tobacco and opium. He also reformed the fiscal administration, greatly improving the state of the Qing treasury. During Yongzheng's reign, the Manchu Empire became a great power and a peaceful country, and ensuring the Kangqian Period of Harmony (康乾盛世), a period of continued development for China. In response to the tragedy surrounding his father’s death, he created a sophisticated procedure for selecting his successor.

During the Yongzheng Emperor’s reign, the government promoted Chinese settlement of the southwest and tried to integrate non-Han aboriginal groups into Chinese culture. Yongzheng placed his trust in Mandarin Chinese officials, giving Li Wei (李卫), a famous mandarin, and Tian Wenjing responsibility for governing China's southern areas. Ertai also served Yongzheng as a governor of the southern regions.

Yongzheng also strengthened the authority of the throne by removing the Princes as commanders of the Eight Banners, the elite Manchu military divisions, and uniting all the Banners under himself, through the "Act of the Union of the Eight Princes" or "八王依正."

Military expansion in the northwest

Like his father, Yongzheng used military force to preserve the Qing dynasty's position in Outer Mongolia. When Tibet was torn by civil war during 1717-28, he intervened militarily, leaving behind a Qing resident backed up by a military garrison to pursue the dynasty's interests. For the Tibetan campaign, Yongzheng sent an army of 230,000 led by Nian GenYiao against the Dzungars, who had an army of 80,000. Though vastly superior in numbers, the Qing army was hampered by the geography of the terrain and had difficulty engaging the mobile enemy. Eventually, the Qing engaged and defeated the enemy. This campaign cost the treasury at least 8,000,000 taels. Later in Yongzheng's reign, he sent another small army of 10,000 to fight the Dzungars. The whole army was annihilated, and the Qing Dynasty nearly lost control of the Mongolian area. However, a Qing ally, the Khalkha tribe, defeated the Dzungars.

After the reforms of 1729, the treasury had over 60,000,000 taels, surpassing the record set during the reign of Yongzhen's father, the Kangxi emperor. However, the pacification of the Qinghai area and the defense of the borders was a heavy burden. For the border defense alone, more than 100,000 taels were needed each year. The total cost of military operations added up to 10,000,000 taels annually. By the end of 1735, military spending had used up half of the treasury, and because of this heavy burden, the Yongzheng emperor considered making peace with the Dzungars.

Death

The Yongzheng Emperor had fourteen children, of which only five survived to adulthood. He died suddenly at the age of fifty-eight, in 1735, after only thirteen years on the throne. According to legends, he was actually assassinated by Lu Siniang, daughter of Lü Liuliang, whose entire family was believed to have been executed for literacy crimes against the Manchu Regime. Some historians believe that he might have died due to an overdose of a medication which he was consuming, believing that it would prolong his life. To prevent the problems of succession which he himself had faced thirteen years ago, he ordered his third son, Hongshi, who had been an ally of Yinsi, to commit suicide. Yongzhen was succeeded by his son, Hongli, the Prince Bao, who became the fifth emperor of the Qing dynasty under the era name of Qianlong.

He was interred in the Western Qing Tombs (清西陵), 120 kilometers (75 miles) southwest of Beijing, in the Tailing (泰陵) mausoleum complex (known in Manchu as the Elhe Munggan).

The Yongzheng Emperor and art

The Yongzheng Emperor was a lover of art who did not follow traditional imperial practices. Unlike the Kangxi Emperor, who had carefully guarded the treasures of the past and taken an interest in preserving and improving on traditional standards of craftsmanship, Yongzheng valued the artistic beauty and uniqueness of the items produced in the Palace Workshops. Traditionally, Chinese artifacts were produced anonymously, but documents from the reign of Yongzheng record the names of over one hundred individual craftsmen. Yongzheng knew his artisans by name and personally commented on their work, rewarding creations that he considered particularly outstanding.

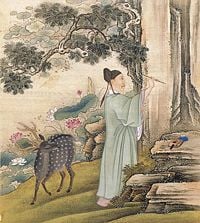

In many of the paintings commissioned by Yongzheng, works of art were depicted in addition to the conventional books and scrolls. He requested that the Jesuit court painter Giuseppe Castiglione (1688—1766) paint “portraits” of his favorite porcelain vases, both ancient and modern. It was customary for an emperor to present himself in a particular light in the paintings called xingle tu (“pictures of pleasurable activities”) by choosing to have himself depicted engaged in specific activities and in particular settings. Yongzheng commissioned a series of fourteen "costume portraits" portraying him as a Confucian scholar with books, writing brush, or qin (a long zither); a Buddhist itinerant monk; a Tibetan lama meditating in a cave; a Daoist immortal with a gourd hanging from his staff; a recluse listening to the waves; a fisherman dreaming; two figures in possession of magic charms: a pearl for summoning a dragon (that is, rain), and a peach of immortality; and three foreigners: a Mongol nobleman, an archer perhaps of a nomadic tribe, and a European hunter wearing a wig.[1]

Yongzheng and Catholicism

The Kangxi emperor had been unsuccessful in stopping the spread of Catholicismin China. After the Yongzhen emperor ascended the throne in 1722, an incident occurred in Fujian when the Catholic missionary there asked his followers to repair the church building. Members of the public protested and a judge, Fu Zhi, who personally visited the church to ban the reconstruction, was confronted by angry Catholics. As a result, in June of 1723, the Governor of Fujian ordered the Catholic missionary to be deported to Macao. The Governor reported the incident to Yongzheng, and requested that he instate a law deporting all missionaries from China. The law was passed in November of the same year, and most of the Catholic missionaries were forced to go to Macao. Their churches were torn down or converted to schools, warehouses, or town halls. In 1729, Yongzheng ordered the expulsion of any missionaries who had remained in hiding. Only twenty were allowed to remain in China, on the condition that they did not preach or proselytize.

Family

- Father: The Kangxi Emperor (of whom he was the 4th son)

- Mother: Concubine from the Manchu Uya clan (1660-1723), who was made the Ren Shou Dowager Empress (仁壽皇太后) when her son became Emperor, and is known posthumously as Empress Xiao Gong Ren (Chinese: 孝恭仁皇后; Manchu: Hiyoošungga Gungnecuke Gosin Hūwanghu)

Consorts

- Empress Xiao Jing Xian (c. 1731) of the Ula Nara Clan (Chinese: 孝敬憲皇后; Manchu: Hiyoošungga Ginggun Temgetulehe Hūwanghu)

- Empress Xiao Sheng Xian (1692-1777) of the Niohuru Clan (Chinese: 孝聖憲皇后; Manchu: Hiyoošungga Enduringge Temgetulehe Hūwanghu), mother of Hongli (Emperor Qianlong)

- Imperial Noble Consort Dun Shu (年贵妃), sister of Nian Gengyao, bore three sons and a daughter, none of which survived

- Imperial Noble Consort Chun Yi (懿贵妃) of Geng, mother of Hongzhou

- Consort Ji (齐妃) of Li, mother of Hongshi

- Consort Qian (谦妃) of the Liu clan, bore Yongzheng's youngest son

- Imperial Concubine Mau of the Song clan, bore two daughters

- Worthy Lady Wu

Sons

- Honghui (弘暉),端親王

- Hongpan

- Hongyun (弘昀), died young

- Hongshi(弘時)

- Hongli(弘曆) (Qianlong Emperor)

- Hongzhou (弘晝), Prince He 和恭親王

- Fuhe (福宜), died young

- Fuhui (福惠),懷親王

- Fupei (福沛), died young

- Hongzhan (弘瞻),果恭郡王

- (弘昐), died young

Daughters

- 4 daughters (1 survived)

Modern media

Although his name is seldom included in reference, Yongzheng was an inseparable part of the era known as the Kangqian Period of Harmony, where China saw continued development. China's CCTV-1 broadcast one of the best-rated television Series in Chinese history on Yongzheng in 1997, portraying him in a positive light and highlighting his tough stance on corruption, an important issue in contemporary China.

Notes

- ↑ Regina Krahl, Yongzheng period. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Feng, Erkang. 1985. 雍正传. Yongzheng zhuan. Zhongguo li dai di wang zhuan ji. Beijing: Ren min chu ban she. ISBN 701000482X.

- Kessler, Lawrence D. 1976. Kʻang-Hsi and the Consolidation of Chʻing Rule, 1661-1684. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226432038.

- Morton, W. Scott, and Charlton M. Lewis. 2005. China: Its History and Culture. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0071412794.

- Peterson, William J. 2002. The Cambridge History of China. Cambridge University Press.

- Tao, Jinsheng. 1977. The Jurchen in Twelfth-Century China: A Study of Sinicization. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295955147.

- Tillman, Hoyt Cleveland, and Stephen H. West. 1995. China under Jurchen Rule: Essays on Chin Intellectual and Cultural History. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0585045399.

- Wu, Silas H.L. 1979. Passage to Power: Kʻang-Hsi and His Heir Apparent, 1661-1722. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674656253.

| House of Aisin-Gioro Born: December 13 1678; Died: October 8 1735 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: The Kangxi Emperor |

Emperor of China 1722-1735 |

Succeeded by: The Qianlong Emperor |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.