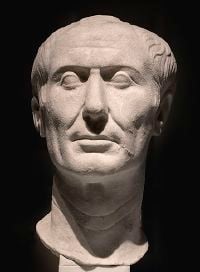

Julius Caesar

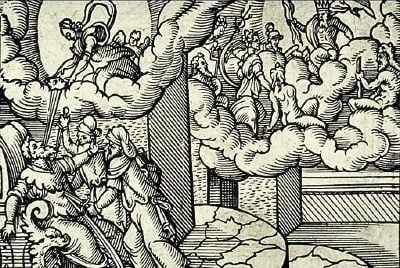

Gaius Julius Caesar (July 13, 100 B.C.E. – March 15, 44 B.C.E.) was a Roman military and political leader whose role in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire changed the course of Western civilization. His conquest of Gaul extended the Roman world all the way to the Atlantic Ocean, and he was also responsible for the first Roman invasion of Britannia (Great Britain), in 55 B.C.E. Caesar is widely considered to be one of the foremost military geniuses of all time, as well as a brilliant politician and orator. Caesar fought in a civil war that left him undisputed master of the Roman world, and after assuming control of the government began extensive reforms of Roman society and government. He extended Roman citizenship to all within the Empire, introduced measures that protected marriage and the institution of the family, reduced the national debt, and showed genuine concern for the welfare of ordinary Romans. Caesar was proclaimed dictator for life, and he heavily centralized the bureaucracy of the Republic. Ironically, this forced the hand of a friend of Caesar, Marcus Junius Brutus, who then conspired with others to murder the great dictator and restore the Republic. This dramatic assassination on the Ides of March (March 15) in 44 B.C.E. sparked a new civil war in Rome, leading to the ascension of Caesar Augustus, further consolidation of political power based on recent precedent, and the formal founding of the Roman Empire. Caesar's military campaigns are known in detail from his own written Commentaries (Commentarii), and many details of his life are recorded by later historians, such as Appian, Suetonius, Plutarch, Cassius Dio, and Strabo. Other information can be gleaned from other contemporary sources, such as the letters and speeches of Caesar's political rival Cicero, the poetry of Catullus, and the writings of the historian Sallust. LifeEarly lifeJulius Caesar was born in Rome, into a patrician family (gens Julia), which supposedly traced its ancestry to Iulus, the son of the Trojan prince Aeneas (who according to myth was the son of Venus). According to legend, Caesar was born by Caesarean section and is the procedure's namesake, though this seems unlikely because at the time the procedure was only performed on dead women, while Caesar's mother lived long after he was born. This legend is more likely a modern invention, as the origin of the Caesarian section is in the Latin word for "cut," caedo, -ere, caesus sum. Caesar was raised in a modest apartment building (insula) in the Subura, a lower-class neighborhood of Rome. Although of impeccable aristocratic patrician stock, the Julii Caesares were not rich by the standards of the Roman nobility. No member of his family had achieved any outstanding prominence in recent times, though in Caesar's father's generation there was a period of great prosperity. He was the namesake of his father (a praetor who died in 85 B.C.E., and his mother was Aurelia Cotta. His elder sister, Julia, was grandmother to Caesar Augustus. His paternal aunt, also known as Julia, married Gaius Marius, a talented general and reformer of the Roman army. Marius became one of the richest men in Rome at the time. As he gained political influence, Caesar's family gained wealth. Towards the end of Marius' life in 86 B.C.E., internal politics reached a breaking point. During this period, Roman politicians were generally divided into two factions: The Populares, which included Marius and were in favor of radical reforms; and the Optimates, which included Lucius Cornelius Sulla and worked to maintain the status quo. A string of disputes between these two factions led to civil war and eventually opened the way to Sulla's dictatorship. Caesar was tied to the Populares through family connections. Not only was he Marius's nephew, he was also married to Cornelia, the youngest daughter of Lucius Cornelius Cinna, Marius's greatest supporter and Sulla's enemy. To make matters worse, in the year 85 B.C.E., just after Caesar turned 15, his father became ill and died. Both Marius and his father had left Caesar much of their property and wealth in their wills. When Sulla emerged as the winner of this civil war and began his program of proscriptions, Caesar, not yet 20 years old, was in a bad position. Now dictator, Sulla ordered Caesar to divorce Cornelia in 82 B.C.E., but Caesar refused and prudently fled Rome to hide. Sulla later pardoned Caesar and his family and allowed him to return to Rome. In a prophetic moment, Sulla was said to comment on the dangers of letting Caesar live. According to Suetonius, the dictator in relenting on Caesar's proscription said, "He whose life you so much desire will one day be the overthrow of the part of nobles, whose cause you have sustained with me; for in this one Caesar, you will find many a Marius." Despite Sulla's pardon, Caesar did not remain in Rome and left for military service in Asia and Cilicia. When the Romans laid siege to Mytilene, on the island of Lesbos, he was dispatched to Bithynia, on the southern coast of the Black Sea, to persuade King Nicomedes IV Philopator to make his fleet available to Marcus Minucius Thermus in the Aegean Sea. The King agreed to dispatch the fleet, though the ease with which Caesar secured the fleet led some to believe that it was in return for sexual favors. The idea of a patrician playing the role of a male prostitute stirred up a scandal back in Rome. His enemies later accused him of this affair on numerous occasions, and it haunted him for his entire political career. In 80 B.C.E., while still serving under Marcus Minucius Thermus, Caesar played a pivotal role in the siege of Miletus. During the course of the battle, Caesar showed such personal bravery in saving the lives of legionaries that he was later awarded the corona civica (oak crown). The award, the second highest (after the corona graminea—Grass Crown) Roman military honor, was bestowed for saving the life of another soldier, and when worn in public, even in the presence of the Roman Senate, all were forced to stand and applaud his presence. It was to be worn one day, and thereafter on festive occasions, and Caesar took full advantage of it, as he started balding. The oak crown was accompanied by a small badge, which could be worn permanently as a symbol of the recipient's courage. After two years of unchallenged power, Sulla acted as no other dictator has since. He disbanded his legions, re-established consular government (in accordance to his own rules, he stood for and was elected consul in 80 B.C.E.), and resigned the dictatorship. He dismissed his lictors and walked unguarded in the forum, offering to give account of his actions to any citizen. This lesson in supreme confidence, Caesar later ridiculed—"Sulla did not know his political ABC's." In retrospect, of the two, Sulla was to have the last laugh, as it was he, "lucky" to the end, who died in his own bed. After his second Consulship, he retreated to his coastal villa to write his memoirs and indulge in the pleasures of private life. He died two years later of liver failure brought on, evidently, by the pleasures of private life. His funeral was stupendous, unmatched until that of Augustus in 14 C.E. In 78 B.C.E., on hearing of Sulla's death, Caesar felt it would be safe for him to return to Rome and he began his political career as an advocate for the populares. He became known for his exceptional oratory, accompanied by impassioned gestures and a high-pitched voice, and ruthless prosecution of former governors notorious for extortion and corruption. The great orator Cicero even commented, "Does anyone have the ability to speak better than Caesar?" Although he was an excellent politician, Caesar was unimpressed with the leaders of the populares, and aiming at greater rhetorical mastery, traveled to Rhodes in 75 B.C.E. for philosophical and oratorical studies with the famous teacher, Apollonius Molon, who was earlier the instructor of Cicero himself. Kidnapping by piratesOn the way across the Aegean Sea, Caesar was kidnapped by Cicilian pirates, above whom he managed to maintain superiority even during his captivity. According to Plutarch's retelling of this incident, when the pirates told Caesar they would ransom him for 20 talents of gold, Caesar laughed and told them he was worth at least 50 (12,000 gold pieces). Plutarch suggests this to be an act to decrease the danger of being killed; still, many historians have interpreted it as a humorous incident that anticipates his self-confidence, shown in his future acts as a consul. Caesar also increased his protection by joining with the crews and acting like one of them, even scolding a few when they showed a small sign of ignoring him. After the ransom was paid, Caesar gathered a fleet, and captured the pirates. When the governor of Asia Minor province did not mete out justice to his satisfaction, Plutarch reports, "Caesar left him to his own devices, went to Pergamum, took the robbers out of prison, and crucified them all, just as he had often warned them on the island that he would do, when they thought he was joking." Elections and growing prominenceIn 63 B.C.E., Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius, who had been appointed to the post of Pontifex Maximus by Sulla, died. In a bold move, Caesar put his name up for election to the post. He ran against two of the most powerful members of the boni, the consulars Quintus Lutatius Catulus and Publius Servilius Vatia Isauricus. There were accusations of bribery by all sides in the contest, but Caesar emerged as the victor. The election to the post of Pontifex Maximus was very important to Caesar’s career. The post held vast political and religious authority and firmly placed Caesar in the public eye for the remainder of his career. Caesar was elected to the post of praetor in 62 B.C.E. After his praetorship, Caesar was allotted Hispania Ulterior (Outer Iberian peninsula) as his province. Caesar’s governorship was a military and civil success and he was able to expand Roman rule. As a result, he was hailed as Imperator by his soldiers, and gained support in the Senate to grant him a triumph. However, upon his return to Rome, Marcus Porcius Cato (known as Cato the Younger) blocked Caesar’s request to stand for the consulship of 60 B.C.E. (or 59 B.C.E.) in absentia. Faced with the choice between a Triumph and consulship, Caesar chose the consulship. First consulship and first triumvirateIn 60 B.C.E. (or 59 B.C.E.), the Centuriate Assembly elected Caesar senior Consul of the Roman Republic. His junior partner was his political enemy Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus, an Optimate and son-in-law of Cato the Younger. Bibulus' first act as Consul was to retire from all political activity in order to search the skies for omens. This apparently pious decision was designed to make Caesar's life difficult during his Consulship. Roman satirists ever after referred to the year as "the consulship of Julius and Caesar," as Romans expressed the time period by the consuls that were elected. Caesar needed allies and he found them where none of his enemies expected. The leading general of the day, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great), was unsuccessfully fighting the Senate for farmlands for his veterans. A former Consul, Marcus Licinius Crassus, allegedly the richest man in Rome, was also having problems in obtaining relief for his publicani clients, the tax-farmers who were in charge of collecting Roman tributes. Caesar desperately needed Crassus's money and Pompey's influence, and an informal alliance soon followed: The First Triumvirate (rule by three men). To confirm the alliance, Pompey married Julia, Caesar's only daughter. Despite their differences in age and upbringing, this political marriage proved to be a love match. Gallic warsCaesar was then appointed to a five year term as Proconsular Governor of Transalpine Gaul (current southern France) and Illyria (the coast of Dalmatia). Not content with an idle governorship, Caesar launched the Gallic Wars (58 B.C.E.–49 B.C.E.) in which he conquered all of Gaul (the rest of current France, with most of Switzerland and Belgium, effectively western mainland Europe from the Atlantic to the Rhine) and parts of Germania and annexed them to Rome. Among his legates were his cousins, Lucius Julius Caesar and Mark Antony, Titus Labienus and Quintus Tullius Cicero, the younger brother of Caesar's political opponent, Cicero. Caesar defeated the Helvetii (in Switzerland) in 58 B.C.E., the Belgic confederacy and the Nervii in 57 B.C.E. and the Veneti in 56 B.C.E. On August 26, 55 B.C.E., he attempted an invasion of Britain and, in 52 B.C.E. he defeated a union of Gauls led by Vercingetorix at the battle of Alesia. He recorded his own accounts of these campaigns in Commentarii de Bello Gallico ("Commentaries on the Gallic War"). According to Plutarch and the writings of scholar Brendan Woods, the whole campaign resulted in 800 conquered cities, 300 subdued tribes, one million men sold into slavery, and another three million dead in battle. Ancient historians notoriously exaggerated numbers of this kind, but Caesar's conquest of Gaul was certainly the greatest military invasion since the campaigns of Alexander the Great. The victory was also far more lasting than those of Alexander's: Gaul never regained its Celtic identity, never attempted another nationalist rebellion, and remained loyal to Rome until the fall of the Western Empire in 476 C.E. Fall of the first triumvirateDespite his successes and the benefits to Rome, Caesar remained unpopular among his peers, especially the conservative faction, who suspected him of wanting to be king. In 55 B.C.E., his partners, Pompey and Crassus, were elected consuls and honored their agreement with Caesar by prolonging his proconsul-ship for another five years. This was the last act of the First Triumvirate. In 54 B.C.E., Caesar's daughter Julia died in childbirth, leaving both Pompey and Caesar heartbroken. Crassus was killed in 53 B.C.E. during his campaign in Parthia. Without Crassus or Julia, Pompey drifted towards the Optimates. Still in Gaul, Caesar tried to secure Pompey's support by offering him one of his nieces in marriage, but Pompey refused. Instead, Pompey married Cornelia Metella, the daughter of Caecilius Metellus, one of Caesar's greatest enemies. The civil warIn 50 B.C.E., the Senate, led by Pompey, ordered Caesar to return to Rome and disband his army because his term as Proconsul had finished. Moreover, the Senate forbade Caesar to stand for a second consulship in absentia. Caesar thought he would be prosecuted and politically marginalized if he entered Rome without the immunity enjoyed by a Consul or without the power of his army. Pompey accused Caesar of insubordination and treason. On January 10, 49 B.C.E., Caesar crossed the Rubicon (the frontier boundary of Italy) with one legion and ignited civil war. Historians differ as to what Caesar said upon crossing the Rubicon; the two competing lines are "Alea iacta est" ("The die is cast") and "Let the dice fly high!" (a line from the New Comedy poet, Menander). (This minor controversy is occasionally seen in modern literature when an author attributes the less popular Menander line to Caesar.) The Optimates, including Metellus Scipio and Cato the Younger, fled to the south, not knowing that Caesar had only his Thirteenth Legion with him. Caesar pursued Pompey to Brindisium, hoping to restore their alliance of ten years prior. Pompey managed to elude him, however. So instead of giving chase Caesar decided to head for Hispania saying, "I set forth to fight an army without a leader, so as later to fight a leader without an army." Leaving Marcus Aemilius Lepidus as prefect of Rome, and the rest of Italy under Mark Antony, Caesar made an astonishing 27-day route-march to Hispania, where he defeated Pompey's lieutenants. He then returned east, to challenge Pompey in Greece, where on July 10, 48 B.C.E., at Dyrrhachium, Caesar barely avoided a catastrophic defeat. He decisively defeated Pompey, despite Pompey's numerical advantage (nearly twice the number of infantry and considerably more cavalry), at Pharsalus in an exceedingly short engagement in 48 B.C.E. In Rome, Caesar was appointed dictator, with Marcus Antonius as his Master of the Horse; Caesar resigned this dictatorship after eleven days and was elected to a second term as consul with Publius Servilius Vatia Isauricus as his colleague. He then pursued Pompey to Alexandria, where Pompey was murdered by an officer of Ptolemy XIII of Egypt. Caesar then became involved with the Alexandrine civil war between Ptolemy and his sister, wife, and co-regnant queen, the Pharaoh Cleopatra VII of Egypt. Perhaps as a result of Ptolemy's role in Pompey's murder, Caesar sided with Cleopatra; he is reported to have wept at the sight of Pompey's head, which was offered to him by Ptolemy's chamberlain, Pothinus, as a gift. In any event, Caesar defeated the Ptolemaic forces and installed Cleopatra as ruler, with whom he fathered his only known biological son, Ptolemy XV Caesar, better known as "Caesarion." Cleopatra then moved into an elaborate estate in Rome. Caesar and Cleopatra never married. In fact they could not marry. As Roman law stood, the institution of marriage was only recognized between two Roman citizens and as Cleopatra was Queen of Egypt, she was not a Roman citizen. In Roman eyes, this did not even constitute adultery, which could only occur between two Roman citizens. Caesar is believed to have committed adultery numerous times during his last marriage, which lasted 14 years but produced no children. After spending the first months of 47 B.C.E. in Egypt, Caesar went to the Middle East, where he annihilated King Pharnaces II of Pontus in the battle of Zela; his victory was so swift and complete that he commemorated it with the famous words Veni, vidi, vici ("I came, I saw, I conquered"). Thence, he proceeded to Africa to deal with the remnants of Pompey's senatorial supporters. He quickly gained a significant victory at Thapsus in 46 B.C.E. over the forces of Metellus Scipio (who died in the battle) and Cato the Younger (who committed suicide). Nevertheless, Pompey's sons Gnaeus Pompeius and Sextus Pompeius, together with Titus Labienus, Caesar's former propraetorian legate (legatus propraetore) and second in command in the Gallic War, escaped to Hispania. Caesar gave chase and defeated the last remnants of opposition in the Munda in March 45 B.C.E. During this time, Caesar was elected to his third and fourth terms as consul in 46 B.C.E. (with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus) and 45 B.C.E. (without any colleague). Aftermath of the civil warCaesar returned to Italy in September 45 B.C.E. Among his first tasks he filed his will, naming Octavian Augustus as the heir to everything he had including his title. Caesar also wrote that if Octavian died before Caesar did, Marcus Junius Brutus would inherit everything. That also applied to a situation where, if Octavian died after inheriting everything, Brutus would inherit it from Octavian. The Senate had already begun bestowing honors on Caesar in absentia. Caesar had not proscribed his enemies, instead pardoning nearly every one of them, and there seemed to be little open resistance to him. Great games and celebrations were held on April 21, to honor Caesar’s great victory. Along with the games, Caesar was honored with the right to wear triumphal clothing, including a purple robe (reminiscent of the kings of Rome) and laurel crown, on all public occasions. A large estate was being built at Rome’s expense, and on state property, for Caesar’s exclusive use. The title of Dictator became a legal title that he could use in his name for the rest of his life. An ivory statue in his likeness was to be carried at all public religious processions. Images of Caesar show his hair combed forward in an attempt to conceal his baldness. Another statue of Caesar was placed in the temple of Quirinus with the inscription "To the Invincible God." Since Quirinus was the deified likeness of the city and its founder and first king, Romulus, this act identified Caesar not only on equal terms with the gods, but with the ancient kings as well. A third statue was erected on the capitol alongside those of the seven Roman Kings and with that of Lucius Junius Brutus, the man who led the revolt to expel the Kings originally. In yet more ostentatious behavior, Caesar had coins minted bearing his likeness. This was the first time in Roman history that a living Roman was featured on a coin. When Caesar returned to Rome in October of 45 B.C.E., he gave up his fourth Consulship (which he held without colleague) and placed Quintus Fabius Maximus and Gaius Trebonius as suffect consuls in his stead. This irritated the Senate because he completely disregarded the Republican system of election and performed these actions at his own whim. He then celebrated a fifth triumph, this time to honor his victory in Hispania. The Senate continued to encourage more honors. A temple to Libertas was to be built in his honor, and he was granted the title Liberator. The Senate elected him Consul for life, and allowed to hold any office he wanted, including those generally reserved for plebeians. Rome also seemed willing to grant Caesar the unprecedented right to be the only Roman to own imperium. In this, Caesar alone would be immune from legal prosecution and would technically have the supreme command of the legions. More honors continued, including the right to appoint half of all magistrates, which were supposed to be elected positions. He also appointed magistrates to all provincial duties, a process previously done by draw of lots or through the approval of the Senate. The month of his birth, Quintilis, was renamed Julius (hence, the English "July") in his honor and his birthday, July 13, was recognized as a national holiday. Even a tribe of the people’s assembly was to be named for him. A temple and priesthood, the Flamen maior, was established and dedicated in honor of his family. Social reformsCaesar, however, did have a reform agenda and took on various social ills. He passed a law that prohibited citizens between the ages of 20 and 40 from leaving Italy for more than three years unless on military assignment. This theoretically would help preserve the continued operation of local farms and businesses and prevent corruption abroad. If a member of the social elite did harm or killed a member of the lower class, then all the wealth of the perpetrator was to be confiscated. Caesar demonstrated that he still had the best interest of the state at heart, even if he believed that he was the only person capable of running it. A general cancellation of one-fourth of all debt also greatly relieved the public and helped to endear him even further to the common population. Caesar is said to have enjoyed the support of the general people, for whose welfare he was genuinely concerned. He also enlarged the Senate and extended citizenship. One of the most significant reforms that he introduced was legislation to support marriage and family as the glue of social stability. His successor continued this trend, outlawing adultery. He appears to have believed that an Empire that was seen to be interested in the health of its citizens would be easier to govern than one that exploited and neglected its people. There was a concern that families were disintegrating, that the traditional role of the father as paterfamilias or head of the household was compromised by women and children acting independently. Previously, men could do what they wanted with their children; in law, they owned them. Now, the idea started to emerge that while the father was head of the family, the best way to discipline children is through encouragement and use of reason. Roman men seemed to have preferred subordinate women, and complained loudly about women who were too powerful or wealthy, especially if they were richer than their husbands. However, Caesar knew that as the basic unit of society, the family was the microcosm of the wider empire. Harmony within the family could translate into a more peaceful empire. Moral families meant a moral empire. There was awareness here that moral laxity in one area, such as sexual relations, spills over into other areas and that leaders who were unfaithful in marriage might also be untrustworthy in public office. Caesar tightly regulated the purchase of state-subsidized grain, and forbade those who could afford privately supplied grain from purchasing from the grain dole. He made plans for the distribution of land to his veterans and for the establishment of veteran colonies throughout the Roman world. One of his most long lasting and influential reforms was the complete overhaul of the Roman calendar. Caesar had been elected Pontifex Maximus in 63 B.C.E. This title has since been appropriated by the popes who carry it on into modern times, being referred to as Supreme Pontiff. One of the roles of Pontifex Maximus was the setting of the calendar. In 46 B.C.E., Caesar established a 365-day year with a leap year every fourth year (this Julian Calendar was subsequently modified by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582 C.E., into the modern calendar). As a result of this reform, the year 46 B.C.E. was 445 days long to bring the calendar into line. Additionally, great public works were undertaken. Rome was a city of great urban sprawl and unimpressive brick architecture and the city desperately needed a renewal. A new Rostra of marble, along with court houses and marketplaces were built. A public library under the great scholar Marcus Terentius Varro was also under construction. The Senate house, the Curia Hostilia, which had been recently repaired, was abandoned for a new marble project to be called the Curia Julia. The forum of Caesar, with its Temple of Venus Genetrix, was built. The city Pomerium (sacred boundary) was extended allowing for additional growth. Unfortunately, all of the pomp, circumstance, and public taxpayers' money being spent incensed certain members of the Roman Senate. One of these was Caesar's closest friend, Marcus Junius Brutus. The assassination plot Caesar was the first living man to appear on a Roman Republican coin. Coin from CNG coins http://www.cngcoins.com, through Wildwinds. Used with permission. Plutarch records that at one point, Caesar informed the Senate that his honors were more in need of reduction than augmentation, but withdrew this position so as not to appear ungrateful. He was given the title Pater Patriae ("Father of the Fatherland"). He was appointed dictator a third time, and then nominated for nine consecutive one-year terms as dictator, effectually making him dictator for ten years. He was also given censorial authority as prefect of morals (praefectus morum) for three years. At the onset of 44 B.C.E., the honors heaped upon Caesar continued and the rift between him and the aristocrats deepened. He had been named Dictator Perpetuus, making him dictator for the remainder of his life. This title even began to show up on coinage bearing Caesar’s likeness, placing him above all others in Rome. Some among the population even began to refer to him as "Rex" (king), but Caesar refused to accept the title, claiming, "Rem Publicam sum!" ("I am the Republic!") At Caesar’s new temple of Venus, a senatorial delegation went to consult with him and Caesar refused to stand to honor them upon their arrival. Though the event is clouded by several different versions of the story, it’s quite clear that the Senators present were deeply insulted. He attempted to rectify the situation later by exposing his neck to his friends and saying he was ready to offer it to anyone who would deliver a stroke of the sword. This seemed to at least cool the situation, but the damage was done. The seeds of conspiracy were beginning to grow. Marcus Junius Brutus began to conspire against Caesar with his friend and brother-in-law, Gaius Cassius Longinus, and other men, calling themselves the Liberatores ("Liberators"). Shortly before the assassination of Caesar, Cassius met with the conspirators and told them that, if anyone found out about the plan, they were going to turn their knives on themselves. On the Ides of March (March 15) of 44 B.C.E., a group of senators called Caesar to the forum for the purpose of reading a petition, written by the senators, asking him to hand power back to the Senate. However, the petition was a fake. Mark Antony, learning of the plot from a terrified senator named Casca, went to head Caesar off at the steps of the forum. However, the group of senators intercepted Caesar just as he was passing the Theatre of Pompey, and directed him to a room adjourning the east portico. As Caesar began to read the false petition, the aforementioned Servilius Casca, pulled down Caesar's tunic and made a glancing thrust at the dictator's neck. Caesar turned around quickly and caught Casca by the arm, crying in Latin "Villain Casca, what do you do?" Casca, frightened, called to his fellow senators in Greek: "Help, brothers!" ("αδελφέ βοήθει!" in Greek, "adelphe boethei!"). Within moments, the entire group, including Brutus, was striking out at the great dictator. In a panic, Caesar attempted to get away, but, blinded by blood, he tripped and fell; the men eventually murdering him as he lay, defenseless, on the lower steps of the portico. According to Eutropius, around sixty or more men participated in the assassination. The dictator's last words are, unfortunately, not known with certainty, and are a contested subject among scholars and historians alike. In Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, Caesar's last words are given as "Et tu, Brute" ("And [even] you, Brutus?"). His actual last words are most widely believed to be "Tu quoque, Brute, fili mi" ("You also, Brutus, my son?"), or "Tu quoque, mi fili?" ("you also, my son?") It is possible, however, that these phrases are translations or adaptations of his last words, which he spoke in Greek, into Latin; Suetonius stated that Caesar said, in Greek, "καί σύ τέκνον;" (transliterated as "kai su, teknon," or "you too my child"). Regardless of what Caesar said, shortly after the assassination the senators left the building talking excitedly amongst themselves, and Brutus cried out to his beloved city: "People of Rome, we are once again free!" However, this was not the end. The assassination of Caesar sparked a civil war in which Mark Antony, Octavian (later Augustus Caesar), and others fought the Roman Senate for both revenge and power. Aftermath of assassinationCaesar's death also marked, ironically, the end of the Roman Republic, for which the assassins had struck him down. The Roman middle and lower classes, with whom Caesar was immensely popular, and had been since Gaul and before, were enraged that a small group of high-browed aristocrats had killed their champion. Antony did not give the speech Shakespeare penned for him ("Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears…"), but he did give a dramatic eulogy which appealed to the common people, a perfect example of what public thinking was following Caesar's murder. Antony, who had been as of late drifting from Caesar, capitalized on the grief of the Roman mob and threatened to unleash them on the Optimates, perhaps with the intent of taking control of Rome himself. But Caesar named his grandnephew, Gaius Octavian, sole heir of his vast fortune, giving Octavius both the immensely powerful Caesar name and control of one of the largest amounts of money in the Republic. In addition, Gaius Octavius was also, for all intents and purposes, the son of the great Caesar, and consequently the loyalty of the Roman populace shifted from dead Caesar to living Octavius. Octavius, only aged 19 at the time of Caesar's death, proved to be ruthless and lethal, and while Antony dealt with Decimus Brutus in the first round of the new civil wars, Octavius consolidated his position. In order to combat Brutus and Cassius, who were massing an army in Greece, Antony needed both the cash from Caesar's war chests and the legitimacy that Caesar's name would provide in any action he took against the two. A new Triumvirate was found—the Second and final one—with Octavian, Antony, and Caesar's loyal cavalry commander Lepidus as the third member. This Second Triumvirate deified Caesar as Divus Iulius and—seeing that Caesar's clemency had resulted in his murder—brought back the horror of proscription, abandoned since Sulla, and proscribed its enemies in large numbers in order to seize even more funds for the second civil war against Brutus and Cassius, whom Antony and Octavian defeated at Philippi. A third civil war then broke out between Octavian on one hand and Antony and Cleopatra on the other. This final civil war, culminating in Antony and Cleopatra's defeat at Actium, resulted in the ascendancy of Octavian, who became the first Roman emperor, under the name Caesar Augustus. In 42 B.C.E., Caesar was formally deified as "the Divine Julius" (Divus Iulius), and Caesar Augustus henceforth became Divi filius ("Son of a God"). Caesar's literary worksCaesar was considered during his lifetime to be one of the finest orators and authors of prose in Rome—even Cicero spoke highly of Caesar's rhetoric and style. Among his most famous works were his funeral oration for his paternal aunt Julia and his Anticato, a document written to blacken Cato the Younger's reputation and respond to Cicero's Cato memorial. Unfortunately, the majority of his works and speeches have been lost to history. Very little of Caesar's poetry survives. One of the poems he is known to have written is The Journey. Memoirs

Other works historically attributed to Caesar, but whose authorship is doubted, are:

These narratives, apparently simple and direct in style—to the point that Caesar's Commentarii are commonly studied by first and second year Latin students—are in fact highly sophisticated advertisements for his political agenda, most particularly for the middle-brow readership of minor aristocrats in Rome, Italy, and the provinces. AssessmentMilitary careerHistorians place the generalship of Caesar on the level of such geniuses as Alexander the Great, Hannibal, Genghis Khan, and Napoleon Bonaparte. Although he suffered occasional tactical defeats, such as Battle of Gergovia during the Gallic War and The Battle of Dyrrhachium during the Civil War, Caesar's tactical brilliance was highlighted by such feats as his circumvallation of Battle of Alesia during the Gallic War, the rout of Pompey's numerically superior forces at Pharsalus during the Civil War, and the complete destruction of Pharnaces's army at Battle of Zela. Caesar's successful campaigning in any terrain and under all weather conditions owes much to the strict but fair discipline of his legionaries, whose admiration and devotion to him was proverbial due to his promotion of those of skill over those of nobility. Caesar's infantry and cavalry was first rate, and he made heavy use of formidable Roman artillery; additional factors which made him so effective in the field were his army's superlative engineering abilities and the legendary speed with which he maneuvered (Caesar's army sometimes marched as many as 40 miles a day). His army was made of 40,000 infantry and many cavaliers, with some specialized units such as engineers. He records in his Commentaries on the Gallic Wars that during the siege of one Gallic city built on a very steep and high plateau, his engineers were able to tunnel through solid rock and find the source of the spring that the town was drawing its water supply from, and divert it to the use of the army. The town, cut off from their water supply, capitulated at once. Political legacyDomestically, Caesar proved to be a committed reformer. The poor were offered opportunities with the founding of new towns in Gaul and Spain and the reconstruction of cities like Carthage and Corinth. Caesar also reformed systems of taxation to protect Roman subjects from extortion, and made good on payments to veteran soldiers. Debts and inordinately high interest rates were a serious problems in the aftermath of the civil war. In a delicate political compromise, Caesar decreed that debtors should satisfy creditors based on a valuation of their possessions prior to the civil war, deducting whatever interest had been paid. To elevate Rome as a center of learning, Caesar conferred privileges to all teachers of the liberal arts, and many public works were carried out in Italy, including the rebuilding of the ancient Forum in the center of Rome. Caesar also took steps to protect the Jews, who had assisted him during the Egyptian campaign. Notably, Caesar also ordered the reorganization of the calendar to better track the solar year. The annual calendar previously numbered 355 days, with extra days made up by randomly adding an extra month. Following the advice of Cleopatra's astronomer, Caesar added four extra months to the year 46 B.C.E., and established the Julian calendar with 365.25 days. Caesar more than any figure brought about the transition of the Roman republic into a Mediterranean empire, bringing relative peace to nearly one third of the world's population. Caesar's liberal extension of citizenship to non Romans, a policy continued in imperial times, cemented loyalty to Rome through the civil rights and other benefits accorded to citizens. To the dismay of the old aristocracy, Caesar even started to recruit new senators from outside Italy. According to the nineteenth century German historian Theodor Mommsen, Caesar's aim

Other historians, such as Oxford historian Ronald Syme and German historian Matthias Gelzert, argued that larger forces work at work in the movement away from an old Roman aristocracy toward a governing body that drew leaders from throughout Italy and even the Roman provinces. Whether by the force of character of one man or because of historic changes that expanded and centralized Roman authority throughout the Mediterranean world, the rise of Empire following the assassination of Julius Caesar would prove to be a watershed even in world history, with consequences tracing through centuries to the present day. References

|

||||||||||||||||||||||