Aaron Beck

| Aaron Beck | |

Beck in 1942

| |

| Born | Aaron Temkin Beck July 18 1921 Providence, Rhode Island, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Died | November 1 2021 (aged 100) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Fields | Psychiatry |

| Institutions | University of Pennsylvania Beck Institute for Cognitive Behavior Therapy |

| Alma mater | Brown University (AB) Yale University (MD) |

| Doctoral students | Steven D. Hollon Jeffrey Young Gregg R. Henriques |

| Known for | Beck Depression Inventory |

| Spouse | Phyllis W. Beck (m. 1950) |

Aaron Temkin Beck (July 18, 1921¬†‚Äď November 1, 2021) was an American psychiatrist, regarded as the father of cognitive therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). His pioneering methods are widely used in the treatment of clinical depression and various anxiety disorders. An effective treatment for a wide range of mental disorders, CBT has become increasingly popular with therapists and the public alike. With its commonsense and clear principles, self-help books based on CBT approaches have also come to dominate the market. Beck also developed self-report measures for depression and anxiety, notably the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), which became one of the most widely used instruments for measuring the severity of depression.

Noted for his writings on psychotherapy, psychopathology, suicide, and psychometrics, Beck was named one of the "Americans in history who shaped the face of American psychiatry" and one of the "five most influential psychotherapists of all time." Beck's focus in his later years was not only to promote recovery but also to build up resilience to mental distress by developing meaningful aspirations, strengthening positive beliefs of purpose, hope, efficacy, empowerment, and belonging, thus allowing people to fulfill their potential, and live happy and successful lives as valuable members of society.

Life

Aaron Temkin Beck was born in Providence, Rhode Island, on July 18, 1921. He was the youngest of four children born to Elizabeth Temkin and Harry Beck, Jewish immigrants from Ukraine.[1][2] Harry worked as a printer and Elizabeth's family found financial success in tobacco wholesaling; the family belonged to the upwardly-mobile vanguard of Providence's Eastern European-Jewish immigrant community. At the time of Aaron's birth, the Temkin-Becks lived a comfortable, lower-middle class lifestyle and were in the process of putting down roots on Providence's East Side. In 1923, when Aaron was two years old, the family purchased a house at 43/41 Sessions Street in the city's Blackstone neighborhood.[3]

Beck attended John Howland Grammar School, Nathan Bishop Junior High, and Hope Street High School, where he graduated as valedictorian in 1938. As an adolescent, Beck dreamed of becoming a journalist.[3] He matriculated at Brown University, where he graduated magna cum laude in 1942. At Brown, he was elected a member of the Phi Beta Kappa Society and was an associate editor of The Brown Daily Herald.[4] Beck attended Yale Medical School, planning to become an internist and work in private practice in Providence. He graduated from Yale with a Doctor of Medicine in 1946.[5]

Beck was married in 1950 to Phyllis Whitman, and they had four children together: Roy, Judy, Dan, and Alice.[6] Phyllis was the first woman judge on the appellate court of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Their youngest daughter, Alice Beck Dubow, became a judge on the same court,[7] while the older daughter Judith became a prominent CBT educator and clinician, writing the basic text in the field,[8] and co-founding the non-profit Beck Institute.[9]

Beck turned 100 on July 18, 2021, and died on November 1 that year peacefully at his home in Philadelphia.[10]

Career

After receiving his M.D., Beck completed a six-month junior residency in pathology at Rhode Island Hospital and a three-year residency in neurology at Cushing Veterans Administration Hospital in Framingham, Massachusetts. During this time, Beck began to specialize in neurology, reportedly liking the precision of its procedures. However, due to a shortage of psychiatry residents, he was instructed to do a six-month rotation in that field, and he became absorbed in psychoanalysis, despite initial wariness.[5]

After completing his medical internships and residencies from 1946 to 1950, Beck became a fellow in psychiatry at the Austen Riggs Center, a private mental hospital in the mountains of Stockbridge, Massachusetts, where he stayed until 1952.[11] At that time, it was a center of ego psychology with an unusual degree of collaboration between psychiatrists and psychologists, including David Rapaport.[12]

Beck then completed military service as assistant chief of neuropsychiatry at Valley Forge Army Hospital in the United States Military.[13]

Penn psychiatry

Beck joined the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania in 1954.[4] The department chair was Kenneth Ellmaker Appel, a psychoanalyst who was president of the American Psychiatric Association,[14] and whose efforts to expand the presence and relatedness of psychiatry had a big influence on Beck's career. At the same time, Beck began formal training in psychoanalysis at the Philadelphia Institute of the American Psychoanalytic Association.[6]

Beck's closest colleague was Marvin Stein, a friend since their army hospital days to whom Beck looked up to for his scientific rigor in psychoneuroimmunology.[12] Beck's first research project was with Leon J. Saul, a psychoanalyst known for unusual methods such as therapy by telephone or setting homework, who had developed inventory questionnaires to quantify ego processes in the manifest content of dreams (dreams that which can be directly reported by the dreamer). This first major undertaking was aimed at validating the various propositions of psychoanalysis. Beck and Marvin Hurvich, a psychology graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania, developed a new inventory they used to assess "masochistic" hostility in manifest dreams, which they published in 1959.[15] This study found themes of loss and rejection related to depression, rather than inverted hostility as predicted by psychoanalysis.[11] In another experiment, he found that depressed patients sought encouragement or improvement following disapproval, rather than seeking out suffering and failure as predicted by the Freudian anger-turned-inwards theory.[5]

Developing his work with funding from the National Institute of Mental Health, Beck came up with what he would call the Beck Depression Inventory,[16] which he published in 1961 and soon started to market, unsupported by Appel.[12]

Through the 1950s, Beck had adhered to the department's psychoanalytic theories while pursuing experimentation and harboring private doubts. In 1961, however, controversy over whom to appoint as the new chair of psychiatry‚ÄĒspecifically, fierce psychoanalytic opposition to the favored choice of biomedical researcher Eli Robins‚ÄĒbrought matters to a head, an early skirmish in a power shift away from psychoanalysis nationally. Beck tried to remain neutral, putting him at bitter odds with his friend Stein.[12]

Meanwhile, despite having graduated from his Philadelphia training, the American Psychoanalytic Institute had rejected Beck's membership application in 1960, skeptical of his claims of success from relatively brief therapy and advising he conduct further supervised therapy on the more advanced or termination phases of a case, and again in 1961 when he had not done so but outlined his clinical and research work. Such deferments were a tactic used by the institute to maintain the orthodoxy in teaching, but Beck was frustrated.[5]

Private practice

In 1962, Beck requested a sabbatical in order to enter into private practice, which he did for five years.[12] In that same year, he was already making notes about patterns of thoughts in depression. Beck explained his increasing interest in the cognitive model by citing a patient he had been listening to for a year at the Penn clinic. He suggested that she was anxious due to her ego being confronted by her sexual impulses, the psychoanalytic explanation. When she did not seem convinced, he asked her whether she believed this; her response was that she was actually worried that she was being boring, and that she thought this often and with everyone.[5]

He became interested in George Kelly's personal construct theory and Jean Piaget's schemas.[17] Beck's first articles on the cognitive theory of depression, in 1963 and 1964 in the Archives of General Psychiatry, maintained the psychiatric context of ego psychology but then turned to concepts of realistic and scientific thinking in the terms of the new cognitive psychology, extended to the therapeutic arena.[12]

Beck's notebooks were filled with self-analysis, where at least twice a day for several years he wrote out his own "negative" (later "automatic") thoughts, rated with a percentile belief score.[12]

The psychologist who would become most important for Beck was Albert Ellis, whose own faith in psychoanalysis had crumbled,[17] and who had begun presenting his "rational therapy" by the mid-1950s.[18] Psychoanalyst Gerald E. Kochansky remarked in 1975 in a review of one of Beck's books that he could no longer tell if Beck was a psychoanalyst or a devotee of Ellis.[12] Both Beck and Ellis cited aspects of the ancient philosophical system of Stoicism as a forerunner of their ideas.[19] Beck's original treatment manual for depression states, "The philosophical origins of cognitive therapy can be traced back to the Stoic philosophers."[20]

In 1967, becoming active again at University of Pennsylvania, Beck still described himself and his new therapy as neo-Freudian in the ego psychology school, albeit focused on interactions with the environment rather than internal drives. He offered cognitive therapy work as a relatively "neutral" space and a bridge to psychology. With a monograph on depression that Beck published in 1967, "Cognitive Therapy entered the marketplace as a corrective experimentalist psychological framework both for himself and his patients and for his fellow psychiatrists."[12]

Beck's work was presented as a far more scientific and experimentally-based development than psychoanalysis (while being less reductive than Behaviorism). His key principles were not simply based on the general findings and models of cognitive psychology or neuroscience developing at that time, but were derived from personal clinical observations and interpretations in his therapy office.[21]

Cognitive therapy

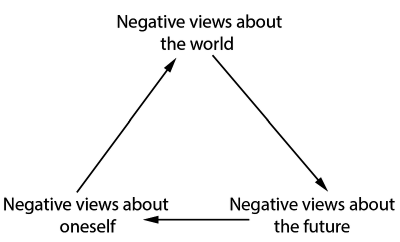

Working with depressed patients, Beck found that they experienced streams of negative thoughts that seemed to arise spontaneously. He discovered that frequent negative thoughts reveal a person's core beliefs, formed over lifelong experiences of these thoughts. Time spent reflecting on these thoughts would lead patients to treat them as valid, to "feel" these beliefs to be true.[22] He termed them "automatic thoughts," and proposed that such cognitions were interrelated as a cognitive triad.[20]

The cognitive triad consists of three major cognitive patterns that induce a person to regard themself in an idiosyncratic way.[20] The three components are negative views of:

- The self

- The world or environment

- The future

Examples of this negative thinking include:

- The self ‚Äď "I'm worthless and undesirable" or "I will never be happy"

- The world ‚Äď "No one values me" or "people ignore me all the time"

- The future ‚Äď "I'm hopeless because things will never change" or "I am going to fail."

Beck began helping patients to identify and evaluate these thoughts, and found that by doing so patients were able to think more realistically, which led them to feel better emotionally and behave more functionally. He proposed that different disorders were associated with different types of distorted thinking. Such thoughts had a negative effect on a person's behavior no matter what type of disorder they had. Beck explained that successful interventions educate a person to understand and become aware of their distorted thinking, and how to challenge its effects.[22]

Beck and his colleagues worldwide researched the efficacy of this form of psychotherapy, known as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), in treating a variety of disorders, including depression, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, drug abuse, anxiety disorders, personality disorders, and many other medical conditions with psychological components.[22]

Although Beck's approach has sometimes been criticized as too mechanistic, CBT stresses the importance of a warm and encouraging therapeutic relationship and tailoring treatment to the specific challenges of each individual.[8] There have been hundreds of outcome studies on the effectiveness of CBT, which show large improvements for emotional disorders in adults and adolescents:

Furthermore, results indicated that CBT was somewhat superior to antidepressants, and equal in efficacy to behaviour therapy in treating adult depression. In recent years, CBT has even been shown to be of benefit when added to medications for patients with schizophrenia.[23]

Questionnaires

Beck's first questionnaire was the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) which became one of the most widely used instruments for measuring the severity of depression. The BDI was first published in 1961[16] and revised as the BDI-2 in 1996.[24] He also developed the Beck Hopelessness Scale (1988, 1993), a 20-item self-report inventory designed to measure three major aspects of hopelessness: feelings about the future, loss of motivation, and expectations. Respondents can either endorse a pessimistic statement or deny an optimistic statement.[25]

Other questionnaires include:

- Clark-Beck Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory (CBOCI)[26]

- Personality Belief Questionnaire (PBQ)

- Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS)

- Suicide Intent Scale (SIS)

- Sociotropy-Autonomy Scale (SAS)

- Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale (CTRS)

- Beck Cognitive Insight Scale (BCIS)

- Satisfaction with Therapy Questionnaire (STQ)

- BDI‚ÄďFast Screen for Medical Patients.[27]

Beck collaborated with psychologist Maria Kovacs on the development of the Children's Depression Inventory (CDI), which used the BDI as a template. The CDI was first published in 1992 and revised in 2010.[28] He also worked with his daughter Judith Beck on the Beck Youth Inventories (BYI).[29]

Legacy

Beck is regarded as the father of cognitive therapy[30] and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).[31] Noted for his writings on psychotherapy, psychopathology, suicide, and psychometrics, he published more than 600 professional journal articles, and authored or co-authored 25 books. He continued his work on psychological therapy right up until his passing at the age of 100, remaining an Emeritus Professor at the University of Pennsylvania and President Emeritus of the Beck Institute until his death.

Beck was named one of the "Americans in history who shaped the face of American psychiatry," and one of the "five most influential psychotherapists of all time."[21] While continuing his work at the University of Pennsylvania as Professor Emeritus of Psychology, Beck inspired Martin Seligman to refine his own cognitive techniques and move away from learned helplessness and toward psychological immunization:

Beck, soon joined by Seligman, postulated that it was not the events themselves but the thoughts we used to explain these events to ourselves that were the major determinants of whether or not, for example, we might develop depression. If so, Beck and Seligman maintained, then people at risk for depression should be able to fend it off by intellectually ‚Äúdisputing‚ÄĚ the severely negative thoughts they think to explain various events in their lives.[32]

In 1994 Beck and his daughter, psychologist Judith S. Beck, founded the nonprofit Beck Institute for Cognitive Behavior Therapy, which provides CBT treatment and training, as well as research.[33] Beck served as President Emeritus of the organization up until his death.

He pioneered the development of Recovery-Oriented Cognitive Therapy (CT-R).[34] This new psychotherapeutic modality is based on the cognitive model and provides concrete, actionable steps to promote recovery and resilience:

Instead of focusing on the troubling symptoms individuals experience, the therapist works with them to develop meaningful aspirations, identify their values, and take steps in pursuit of their goals. ... Dr. Beck often stated that he was more passionate about his work in CT-R than anything else he had done in his career. He viewed CT-R as not only pivotal to the treatment of severe mental health conditions, but to the field of mental health in general.[35]

Beck was the director of the Aaron T. Beck Psychopathology Research Center, which was the parent organization of the Center for the Treatment and Prevention of Suicide. His initial studies of suicide provided a framework for the classification and assessment of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. The researchers at the Center, now known as the Penn Center for the Prevention of Suicide, extended Beck's work to develop a targeted intervention, Cognitive Therapy for Suicide Prevention.[36]

Beck received honorary degrees from Yale University, University of Pennsylvania, Brown University, Assumption College, and Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine. He was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2007.[37]

He also received numerous awards for his work, including:

- The 7th Annual Heinz Award in the Human Condition[30]

- The 1992 James McKeen Cattell Fellow Award

- The 1999 Joseph Zubin Award

- The 2004 University of Louisville Grawemeyer Award for Psychology[38]

- The 2006 Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award[39]

- The 2010 Bell of Hope Award[30]

- The 2010 Sigmund Freud Award

- The 2010 Scholarship and Research Award

- The 2011 Edward J. Sachar Award

- The 2011 Prince Mahidol Award in Medicine

- The 2013 Kennedy Community Mental Health Award

Major works

- Beck, A.T. The Diagnosis and Management of Depression. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1967. ISBN 978-0812276749

- Beck, A.T. Depression: Causes and treatment. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1972. ISBN 978-0812276527

- Beck, A.T. Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. Madison, CT: International Universities Press, Inc., 1975. ISBN 978-0823609901

- Beck, A.T., A.J. Rush, B.F. Shaw, and G. Emery. Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 1979. ISBN 978-0898620009

- Beck, A.T., F.D. Wright, F.F. Newman, and B.D. Liese. Cognitive Therapy of Substance Abuse. New York: Guilford Press, 1979. ISBN 978-1572306592

- Beck, A.T. Love is Never Enough: How Couples Can Overcome Misunderstandings, Resolve Conflicts, and Solve Relationship Problems Through Cognitive Therapy. Harper Perennial, 1989. ISBN 978-0060916046

- Beck, A.T. Prisoners of Hate: The cognitive basis of anger, hostility, and violence. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers, 1999. ISBN 978-0060193775

- Beck, A.T., A. Freeman, and D.D. Davis. Cognitive Therapy of Personality Disorders. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2003. ISBN 978-1572308565

- Beck, A.T., G. Emery, and R.L. Greenberg. Anxiety Disorders and Phobias: A cognitive perspective. New York, NY: Basic Books, 2005. ISBN 978-0465005871

- Beck, A.T., N.A. Rector, N. Stolar, and P. Grant. Schizophrenia: Cognitive theory, research, and therapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1606230183

- Beck, A.T., and B.A. Alford. Depression: Causes and Treatments (2nd ed). Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0812219647

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Jon Marks, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Expert Aaron Beck Going Strong at 96 Jewish Exponent (October 18, 2017). Retrieved February 6, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Kevin A. Fall, Janice Miner Holden, and Andre Marquis, Theoretical Models of Counseling and Psychotherapy (Routledge, 2023, ISBN 978-1032038483).

- ‚ÜĎ 3.0 3.1 Rachel T. Rosner, Aaron T. Beck, the "Golden Ghetto" of Providence, and Cognitive Therapy Rhode Island Jewish Historical Association 17(2) (November 2016): 244-255. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ 4.0 4.1 Catherine Newman, Unseating Freud: Aaron Beck ‚Äô42 created cognitive behavioral therapy, transforming the field of mental health Brown Alumni Magazine (April 11, 2022). Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Daniel B. Smith, The Doctor Is IN The American Scholar (September 1, 2009). Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ 6.0 6.1 Andrew Green, Aaron T Beck The Lancet 399 (June 25, 2022):2344. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Judge Alice Beck Dubow Unified Judicial System of Pennsylvania. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ 8.0 8.1 Judith S. Beck, Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond (The Guilford Press, 2020, ISBN 978-1462544196).

- ‚ÜĎ About Beck Institute Beck Institute for Cognitive Behavior Therapy. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ In Memory of Aaron Temkin Beck, MD Beck Institute for Cognitive Behavior Therapy. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ 11.0 11.1 Aaron T. Beck, A 60-Year Evolution of Cognitive Theory and Therapy Perspectives on Psychological Science 14(1) (2019):16‚Äď20. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 12.5 12.6 12.7 12.8 Rachael I. Rosner, The "Splendid Isolation" of Aaron T. Beck Isis 105(4) (December 2014):734-758. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Aaron T. Beck, born 1921, Papers, 1953 - 2000: Biographical Note University of Pennsylvania University Archives and Records Center. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ The Kenneth E. Appel Professorship of Psychiatry Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Aaron T. Beck and Marvin S. Hurvich, Psychological Correlates of Depression 1. Frequency of ‚ÄúMasochistic‚ÄĚ Dream Content in a Private Practice Sample Psychosomatic Medicine 21(1) (January 1959):50-55. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ 16.0 16.1 Aaron T. Beck et al., An Inventory for Measuring Depression Archives of General Psychiatry 4(6) (June 1961): 561‚Äď571. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ 17.0 17.1 Mark Kelland, Personality Theory February 7, 2024. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Giovanni M. Ruggiero, Marcantonio M. Spada, Gabriele Caselli, and Sandra Sassaroli, A Historical and Theoretical Review of Cognitive Behavioral Therapies: From Structural Self-Knowledge to Functional Processes J Ration Emot Cogn Behav Ther 36(4) (2018):378‚Äď403. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Daniel Robertson, The Philosophy of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy: Stoicism as Rational and Cognitive Psychotherapy (Routledge, 2019, ISBN 978-0367219147).

- ‚ÜĎ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Aaron T. Beck, A. John Rush, Brian F. Shaw, and Gary Emery, Cognitive Therapy of Depression (The Guilford Press, 1987, ISBN 978-0898629194).

- ‚ÜĎ 21.0 21.1 Aaron T. Beck, MD Pearson. Retrieved February 13, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Aaron T. Beck, The past and future of cognitive therapy Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research 6(4) (1997): 276‚Äď284. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Brandon A. Gaudiano, Cognitive-behavioural therapies: achievements and challenges Evid Based Ment Health 11(1) )2008): 5‚Äď7. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Aaron T. Beck, Robert A. Steer, and Gregory K. Brown, Beck Depression Inventory BDI-2 Pearson. Retrieved February 14, 2024

- ‚ÜĎ Aaron T. Beck, Beck Hopelessness Scale Pearson. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ David Clark and Aaron T. Beck, Clark-Beck Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory Pearson. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Aaron T. Beck, Robert A. Steer, and Gregory K. Brown, BDI - FastScreen for Medical Patients Pearson. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Maria Kovacs, Children's Depression Inventory 2 CDI 2 Pearson. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Judith S. Beck and Aaron T. Beck, Beck Youth Inventories BYI-2 Pearson. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Aaron Beck The Heinz Awards. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ S. Hossein Fatemi and Paula J. Clayton, The Medical Basis of Psychiatry (Springer, 2018, ISBN 978-1493979714).

- ‚ÜĎ Rob Hirtz, Martin Seligman‚Äôs Journey From Learned Helplessness to Learned HappinessÔĽŅ The Pennsylvania Gazette (January 1, 1999).

- ‚ÜĎ History of Beck Institute Beck Institute for Cognitive Behavior Therapy. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Jenna Feldman, Mike Best, Aaron T. Beck, Ellen Inverso, and Paul Grant, What is Recovery-Oriented Cognitive Therapy (CT-R)? Beck Institute for Cognitive Behavior Therapy, March 7, 2019. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Dr. Aaron T. Beck Beck Institute for Cognitive Behavior Therapy. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Penn Center for the Prevention of Suicide Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Dr. Aaron T. Beck (1921 ‚Äď 2021) American Academy of Arts & Sciences. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ 2004 ‚Äď Aaron Beck Grawemeyer Awards. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ 2006 Albert Lasker Clinical Medical Research Award: Aaron T. Beck Lasker Foundation. Retrieved February 14, 2024.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beck, Aaron T., A. John Rush, Brian F. Shaw, and Gary Emery. Cognitive Therapy of Depression. The Guilford Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0898629194

- Beck, Judith S. Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond. The Guilford Press, 2020. ISBN 978-1462544196

- Fall, Kevin A., Janice Miner Holden, and Andre Marquis. Theoretical Models of Counseling and Psychotherapy. Routledge, 2023. ISBN 978-1032038483

- Robertson, Daniel. The Philosophy of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy: Stoicism as Rational and Cognitive Psychotherapy. Routledge, 2019. ISBN 978-0367219147

External links

All links retrieved February 14, 2024.

- Beck Institute for Cognitive Behavior Therapy

- CBT Insights Beck Institute

- Dr. Aaron T. Beck Beck Institute

- Academy of Cognitive and Behavioral Therapies (A-CBT)

- Centro de Psicolog√≠a Aaron Beck Espa√Īa

- A Conversation with Aaron T. Beck

- A Brief History of Aaron T. Beck, MD, and Cognitive Behavior Therapy by Judith S. Beck and Sarah Fleming, Clin Psychol Eur. 2021.

- Aaron T. Beck, MD Pearson.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.