Cognitive behavioral therapy

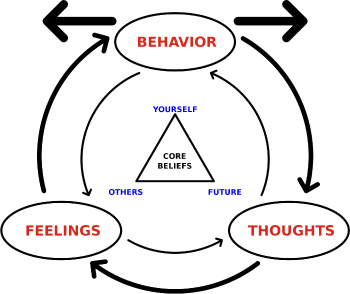

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a form of talk therapy, or psychotherapy, that aims to reduce symptoms of various mental health conditions, primarily depression and anxiety disorders. It focuses on the construction and reconstruction of people's cognitions, emotions, and behaviors by challenging cognitive distortions (such as thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes) and their associated behaviors. Generally in CBT, the therapist, through a wide array of modalities, helps clients assess, recognize, and deal with problematic and dysfunctional ways of thinking, emoting, and behaving.

CBT developed as a combination of cognitive therapy, which focuses directly on changing the person's thoughts, and behavior therapy which focuses on manipulating the external environment and physiological internal environment to cause behavior change, with the intention of improving emotional responses, cognitions, and interactions with others.

Mainstream cognitive behavioral therapy assumes that changing maladaptive thinking leads to change in behavior and affect. Alternatively, some CBT therapists focus on changing the patient's relationship to maladaptive thinking rather than changing their thinking itself.

Overview

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a psychotheraputic intervention that aims to reduce symptoms of various mental health conditions, primarily depression and anxiety disorders. CBT focuses on challenging and changing cognitive distortions (such as thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes) and their associated behaviors to improve emotional regulation[1] and develop personal coping strategies that target solving current problems. Though it was originally designed to treat depression, its uses have been expanded to include many issues and the treatment of many mental health conditions, including anxiety, substance use disorders, marital problems, ADHD, and eating disorders.

Therapists use CBT techniques to help people challenge their patterns and beliefs and replacing errors in thinking, known as cognitive distortions, involving exaggerated or irrational thought patterns.[2] The therapist works to replace these erroneous types of thinking with "more realistic and effective thoughts, thus decreasing emotional distress and self-defeating behavior."[3]

CBT is a common form of talk therapy based on the combination of the basic principles from behavioral and cognitive psychology.[1] It is different from historical approaches to psychotherapy, such as the psychoanalytic approach where the therapist looks for the unconscious meaning behind the behaviors and then formulates a diagnosis. Instead, CBT is a "problem-focused" and "action-oriented" form of therapy, meaning it is used to treat specific problems related to a diagnosed mental disorder. The therapist's role is to assist the client in finding and practicing effective strategies to address the identified goals and to alleviate symptoms of the disorder. CBT is based on the belief that thought distortions and maladaptive behaviors play a role in the development and maintenance of many psychological disorders and that symptoms and associated distress can be reduced by teaching new information-processing skills and coping mechanisms.[4]

History

Maintaining a faith or belief system has often been regarded as entangled with neurotic and psychotic disorders. However, religious and spiritual factors are increasingly being studied as positive contributions to mental well-being, offering powerful sources of comfort, hope, and meaning.[5] Religious institutions have proactively established charities, such as the Samaritans, to address not only physical disease but als mental health issues.[6]

Islam

Islamic psychology, rooted in the Sufi tradition, traces its origins to the eleventh century, notably shaped by Al Ghazali. Al Ghazali conceptualized the self with four integral elements: heart, spirit, soul, and intellect. These components align correspondingly with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) domains, specifically emotions, behaviors, thoughts, and the capacity for reflection.[7]

Philosophy

Precursors of certain fundamental aspects of CBT have been identified in various ancient philosophical traditions, particularly Stoicism.[8] For example, Stoic philosopher Epictetus believed that logic could be used to identify and discard false beliefs that lead to destructive emotions. Aaron T. Beck's original treatment manual for depression states, "The philosophical origins of cognitive therapy can be traced back to the Stoic philosophers."[9]

A more recent philosophical figure who influenced the development of CBT was John Stuart Mill through his creation of Associationism, a predecessor of classical conditioning and behavioral theory.[10]

Behavioral therapy

Groundbreaking work in Behaviorism began with John B. Watson and Rosalie Rayner's studies of conditioning in 1920. Behaviorally-centered therapeutic approaches appeared as early as 1924.[11] These were the antecedents of the development of Joseph Wolpe's behavioral therapy in the 1950s. It was the work of Wolpe and Watson, which was based on Ivan Pavlov's work on learning and conditioning, that influenced Hans Eysenck and Arnold Lazarus to develop new behavioral therapy techniques based on classical conditioning.[12]

In Britain, Wolpe, who applied the findings of animal experiments to his method of systematic desensitization, applied behavioral research to the treatment of neurotic disorders. Wolpe's therapeutic efforts were precursors to today's fear reduction techniques.[11] Hans Eysenck presented behavior therapy as a constructive alternative to psychotherapy (Freudian or otherwise), which he concluded failed to facilitate the recovery of neurotic patients.[11]

At the same time as Eysenck's work, B.F. Skinner and his associates were beginning to have an impact with their work on operant conditioning. Skinner's work was referred to as radical behaviorism and avoided anything related to cognition. However, Julian Rotter in 1954 and Albert Bandura in 1969 contributed to behavior therapy with their works on social learning theory by demonstrating the effects of cognition on learning and behavior modification.[12]

Cognitive therapy

One of the first therapists to address cognition in psychotherapy was Alfred Adler, notably with his idea of basic mistakes and how they contributed to creation of unhealthy behavioral and life goals.[12] Abraham Low believed that someone's thoughts were best changed by changing their actions: the patient must learn to “move his muscles to reeducate the brain.”[13] Adler and Low influenced the work of Albert Ellis, who worked on cognitive treatment methods in the 1950s. He called his approach Rational Therapy (RT) at first, then Rational Emotive Therapy (RET) and later Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT). The first version of REBT was announced to the public in 1956.[12]

In the late 1950s, Aaron T. Beck was conducting free association sessions in his psychoanalytic practice.[1] During these sessions, Beck noticed that thoughts were not as unconscious as Freud had previously theorized, and that certain types of thinking may be the culprits of emotional distress. It was from this hypothesis that Beck developed cognitive therapy, and called these thoughts "automatic thoughts," which when repeated many times became the patient's reality and led them to behave in self-defeating ways.[14]

Aaron T. Beck's cognitive theory of depression suggests that depressed people think the way they do because their thinking is biased towards negative interpretations. Thus, depressed people acquire a negative schema of the world in childhood and adolescence as an effect of stressful life events, and the negative schema is activated later in life when the person encounters similar situations.[15]

Beck also described a negative cognitive triad. The cognitive triad is made up of the depressed individual's negative evaluations of themselves, the world, and the future. Beck suggested that these negative evaluations derive from the negative schemata and cognitive biases of the person. According to this theory, depressed people have views such as "I never do a good job," "It is impossible to have a good day," and "things will never get better." A negative schema helps give rise to the cognitive bias, and the cognitive bias helps fuel the negative schema. Beck further proposed that depressed people often have the following cognitive biases: arbitrary inference, selective abstraction, over-generalization, magnification, and minimization. These cognitive biases are quick to make negative, generalized, and personal inferences of the self, thus fueling the negative schema.[15]

Referred to as "the father of cognitive therapy,"[16] Beck first published his new methodology in 1967, and his first treatment manual in 1979.[1]

Merging the therapies

Although the early behavioral approaches were successful in many so-called neurotic disorders, they had little success in treating depression.[11] Behaviorism was also losing popularity due to the cognitive revolution. The therapeutic approaches of Albert Ellis and Aaron T. Beck gained popularity among behavior therapists, despite the earlier behaviorist rejection of mentalistic concepts like thoughts and cognitions. The approaches of both Ellis and Beck included behavioral elements and interventions, with the primary focus being on problems in the present.

During the 1980s and 1990s, cognitive and behavioral techniques were merged into cognitive behavioral therapy. Pivotal to this merging was the successful development of treatments for panic disorder by David M. Clark in the UK and David H. Barlow in the US.[11]

Types

Over time, cognitive behavior therapy came to be known not only as a therapy, but as an umbrella term for all cognitive-based psychotherapies. These therapies include, but are not limited to, REBT, cognitive therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, dialectical behavior therapy, metacognitive therapy, metacognitive training, reality therapy/choice theory, cognitive processing therapy, EMDR, and multimodal therapy.

Mainstream cognitive behavioral therapy assumes that changing maladaptive thinking leads to change in behavior and affect. Alternatively, some CBT therapists focus on changing the patient's relationship to maladaptive thinking rather than changing their thinking itself. Following are some of the variants of CBT.

Brief cognitive behavioral therapy

Brief cognitive behavioral therapy (BCBT) is a form of CBT which has been developed for situations in which there are time constraints on the therapy sessions and specifically for those struggling with suicidal ideation and/or making suicide attempts. This technique was first implemented and developed with soldiers on active duty by M. David Rudd to prevent suicide.[17] BCBT takes place over a couple of sessions that can last up to 12 accumulated hours by design.

Cognitive emotional behavioral therapy

Cognitive emotional behavioral therapy (CEBT) is a form of CBT developed initially for individuals with eating disorders but now used with a range of problems including anxiety, depression, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and anger problems. It combines aspects of CBT and dialectical behavioral therapy and aims to improve understanding and tolerance of emotions in order to facilitate the therapeutic process. It is frequently used as a "pretreatment" to prepare and better equip individuals for longer-term therapy.[18]

CBT for Suicide Prevention (CBT-SP)

CBT-SP, an adaptation of CBT for suicide prevention (SP), was specifically designed for treating youths who are severely depressed and who have recently attempted suicide within the past 90 days, and was found to be effective, feasible, and acceptable.[19]

Unified Protocol

The Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (UP) is a form of CBT, developed by David H. Barlow and researchers at Boston University, that can be applied to a range of anxiety disorders. Patients often have more than one issue and so therapy that focuses on only one disorder is not satisfactory. Given that many disorders have common underlying causes, they can be treated together.[20]

Barlow suggests that psychological disorders share an underlying structure, made up of three vulnerabilities:

- a generalized biological vulnerability, which consists of a genetically-informed temperamental inclination toward neuroticism and behavioral inhibition;

- generalized psychological vulnerability, which—as early life experiences interact with biological vulnerabilities—create a volatile psychological landscape manifested often in a feeling of lack of control;

- specific psychological vulnerability, which relates to the specific focus, or expression, of stress and anxiety and hence to a particular diagnosis (e.g.: fear of rejection = Social Phobia; fear of physiological arousal = Panic Disorder; fear of bad thoughts = Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)).[21]

It follows that disorders emerging from this common underlying structure can be treated with a common set of therapy procedures. Barlow's proposal includes four therapy components:

- Psycho-education/boosting motivation (increasing self knowledge and becoming a partner in therapy)

- Cognitive reappraisal (learning to think accurately about your thinking)

- Preventing emotional avoidance (accepting emotional experience and increasing emotional literacy)

- Changing behavioral habits in the context of exposure treatment (facing fears and learning new habits)[21]

Applications

CBT has been found to be an effect part of treatment plans for a wide variety of mental disorders, both in adults and younger patients.

Depression and anxiety disorders

According to a 2004 review by the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research, Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale INSERM, of three methods, cognitive behavioral therapy was either proven or presumed to be an effective therapy on several mental disorders, including depression, panic disorder, post-traumatic stress, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, anxiety disorders, eating disorders including bulimia and anorexia, personality disorders. and alcohol dependency.[22]

The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines indicated that, among psychotherapeutic approaches, cognitive behavioral therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy had the best-documented efficacy for treatment of major depressive disorder.[23]

Cognitive behavioral interventions have been found to reduce symptoms of depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder in autistic adults and children without intellectual disability.

Adults with dementia and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) who experience symptoms of depression may also benefit from CBT.

Psychosis

In long-term psychoses, CBT is used to complement medication and is adapted to meet individual needs. Interventions particularly related to these conditions include exploring reality testing, changing delusions and hallucinations, examining factors which precipitate relapse, and managing relapses.[24]

Addictions and substance use disorders

CBT has been found to be effective in helping those with addictions, including problem gambling, addictions to tobacco smoking and internet, as well as substance use disorders.

CBT looks at the habit of smoking cigarettes as a learned behavior, which later evolves into a coping strategy to handle daily stressors. Since smoking is often easily accessible and quickly allows the user to feel good, it can take precedence over other coping strategies, and eventually work its way into everyday life during non-stressful events as well. CBT aims to target the function of the behavior, as it can vary between individuals, and works to inject other coping mechanisms in place of smoking. CBT also aims to support individuals with strong cravings, which are a major reported reason for relapse during treatment.[25]

For individuals with substance use disorders, CBT aims to reframe maladaptive thoughts, such as denial, minimizing, and catastrophizing thought patterns, with healthier narratives.[26] Specific techniques include identifying potential triggers and developing coping mechanisms to manage high-risk situations.

Methods of access

There are different protocols for delivering cognitive behavioral therapy. Treatment is sometimes manualized, with brief, direct, and time-limited treatments for individual psychological disorders that are specific technique-driven. CBT is used in both individual and group settings, and the techniques are often adapted for self-help applications. Some clinicians and researchers are cognitively oriented (for example, cognitive restructuring), while others are more behaviorally oriented (for example, in vivo exposure therapy). Interventions such as imaginal exposure therapy combine both approaches.[27]

Therapist

A typical CBT program would consist of face-to-face sessions between patient and therapist, made up of 6–18 sessions of around an hour each with a gap of 1–3 weeks between sessions. This initial program might be followed by some booster sessions, for instance after one month and three months. Effective cognitive behavioral therapy is dependent on a therapeutic alliance between the healthcare practitioner and the person seeking assistance.[1]

While generally individual CBT sessions with a therapist are more efficacious, patient participation in group courses can also be shown to be effective.

CBT has also been found to be effective if patient and therapist connect virtually, typing in real time to each other via the internet.

Computerized cognitive behavioral therapy (CCBT), also known as internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy or ICBT, has been developed in place of a human therapist.

Self-guided CBT

Self-help CBT guides have been developed which deliver guided self-help to patients. Another new method of access is the use of mobile app or smartphone applications to deliver self-help or guided CBT. Technology companies are developing mobile-based artificial intelligence (AI) chatbot applications in delivering CBT as an early intervention to support mental health, to build psychological resilience, and to promote emotional well-being.

Criticisms

The positive effects of CBT on depression appear to have been declining since 1977. Possible reasons include inadequate therapist training, failure to adhere to a manual, lack of therapist experience, and patients' hope and faith in its efficacy waning as potential reasons.

Furthermore, CBT studies have high drop-out rates compared to other treatments. This high drop-out rate is also evident in the treatment of several disorders, particularly the eating disorder anorexia nervosa, which is commonly treated with CBT. Those treated with CBT have a high chance of dropping out of therapy before completion and reverting to their anorexia behaviors.[28]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Judith S. Beck, Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond (The Guilford Press, 2020, ISBN 978-1462544196).

- ↑ John Grohol, 15 Common Cognitive Distortions PsychCentral, July 2, 2009. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

- ↑ Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT). Pure Psych. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

- ↑ Michael Barhkam, Wolfgang Lutz, and Louis G. Castonguay (eds.), Bergin and Garfield's Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change (John Wiley & Sons Inc, 2021, ISBN 978-1119536581)

- ↑ Harold G. Koenig, "Research on religion, spirituality, and mental health: a review" Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 54(5) (May 2009): 283–291. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

- ↑ Amanda Porterfield, Healing in the History of Christianity (Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0195157185).

- ↑ Amber Haque, "Psychology from Islamic Perspective: Contributions of Early Muslim Scholars and Challenges to Contemporary Muslim Psychologists" Journal of Religion and Health 43(4) (Winter, 2004): 357-377. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

- ↑ Donald Robertson, The Philosophy of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (CBT): Stoic Philosophy as Rational and Cognitive Psychotherapy (Routledge, 2019, ISBN 978-0367219147).

- ↑ Aaron T. Beck, A. John Rush, Brian F. Shaw, and Gary Emery, Cognitive Therapy of Depression (The Guilford Press, 1987, ISBN 978-0898629194).

- ↑ Daniel N. Robinson, An Intellectual History of Psychology (The University of Wisconsin Press, 1995, ISBN 0299148440).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 David M. Clark and Christopher G. Fairburn (eds.), Science and Practice of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (Oxford University Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0192627254).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Danny Wedding and Raymond J. Corsini (eds.), Current Psychotherapies (Cengage Learning, 2018, ISBN 978-1305865754).

- ↑ Michael G. Brock, The truth is indeed sobering Detroit Legal News (March 18, 2015). Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ↑ Erica Goode, A Pragmatic Man and His No-Nonsense Therapy The New York Times (January 11, 2000). Retrieved March 19, 2024.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Ann M. Kring, Sheri L. Johnson, Gerald C. Davison, and John M. Neale, Abnormal psychology (John Wiley and Sons, 2012, ISBN 978-1118018491).

- ↑ Aaron Beck The Heinz Awards. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

- ↑ M. David Rudd, "Brief cognitive behavioral therapy (BCBT) for suicidality in military populations" Military Psychology 24(6) (2012):592–603.

- ↑ Koushiki Choudhury, Managing Workplace Stress: The Cognitive Behavioural Way (Springer, 2014, ISBN 978-8132217381).

- ↑ Barbara Stanley, et al., Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Suicide Prevention (CBT-SP): Treatment Model, Feasibility and Acceptability Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 48(10) (October 2009): 1005–1013. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ↑ Advantages of the Unified Protocol Unified Protocol Institute. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Noam Shpancer, "The Future of Therapy: A Unified Treatment Approach" Psychology Today (January 9, 2011). Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- ↑ INSERM Collective Expertise Centre, Psychotherapy: Three approaches evaluated Paris, France: Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale, 2004. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association, American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders: Compendium 2006 (Amer Psychiatric Pub Inc, 2006, ISBN 978-0890423851).

- ↑ M.I. Gutiérrez López, M. Sánchez Muñoz, A. Trujillo Borrego, and L. Sánchez Bonome, Cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic psychosis Actas Españolas de Psiquiatría 37(2) (2009): 106–114. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ↑ Tobacco Dependence Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- ↑ What Is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy? Expert Dr. Mendonsa Explains Sprout Health Group. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- ↑ Jessamy Hibberd and Jo Usmar, This Book Will Make You Happy (Quercus Publishing, 2023, ISBN 978-1848662810).

- ↑ Heather Jennings, Nolen-Hoeksema's Abnormal Psychology McGraw Hill, 2022, ISBN 978-1265237769).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- American Psychiatric Association. American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines for the Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders: Compendium 2006. Amer Psychiatric Pub Inc, 2006. ISBN 978-0890423851

- Barhkam, Michael, Wolfgang Lutz, and Louis G. Castonguay (eds.), Bergin and Garfield's Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change. John Wiley & Sons Inc, 2021. ISBN 978-1119536581

- Beck, Aaron T., A. John Rush, Brian F. Shaw, and Gary Emery. Cognitive Therapy of Depression. The Guilford Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0898629194

- Beck, Judith S. Cognitive Behavior Therapy: Basics and Beyond. The Guilford Press, 2020. ISBN 978-1462544196

- Clark, David M., and Christopher G. Fairburn (eds.). Science and Practice of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0192627254

- Hibberd, Jessamy, and Jo Usmar. This Book Will Make You Happy. Quercus Publishing, 2023. ISBN 978-1848662810

- Jennings, Heather. Nolen-Hoeksema's Abnormal Psychology. McGraw Hill, 2022. ISBN 978-1265237769

- Porterfield, Amanda. Healing in the History of Christianity. Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0195157185

- Robertson, Donald. The Philosophy of Cognitive-Behavioural Therapy (CBT): Stoic Philosophy as Rational and Cognitive Psychotherapy. Routledge, 2019. ISBN 978-0367219147

- Robinson, Daniel N. An Intellectual History of Psychology. The University of Wisconsin Press, 1995. ISBN 0299148440

- Wedding, Danny, and Raymond J. Corsini (eds.). Current Psychotherapies. Cengage Learning, 2018. ISBN 978-1305865754

External links

All links retrieved April 1, 2024.

- Does Cognitive Therapy = Cognitive Behavior Therapy? The Beck Institute for Cognitive Behavior Therapy

- Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies (ABCT)

- British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies

- National Association of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapists

- Cognitive Behaviour Therapy Sydney

- What is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy? American Psychological Association

- Cognitive behavioral therapy Mayo Clinic

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) Cleveland Clinic

- What Is Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)? VeryWell Mind

- Cognitive behavioral therapy National Library of Medicine

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: What Is It and How Does It Work? Healthline

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Psychology Today

- CBT Techniques: 25 Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Worksheets by Courtney E. Ackerman, Positive Psychology, March 20, 2017.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.