Self-concept or self identity is the mental and conceptual understanding and persistent regard that sentient beings hold for their own existence. It is the sum total of a being's knowledge and understanding of his or her self. The self-concept is different from self-awareness, which is an awareness or evaluation of one's self.

Components of the self-concept include physical, psychological, and social attributes. One's self-concept develops over time as these attributes develop and as one becomes better able to assess them. Such self-evaluation is influenced both by the individual's attitudes, habits, beliefs, and ideas and by how they are perceived by others in their social environment, perceptions that may be positive or negative. In other words, human beings understand themselves both as individuals seeking to fulfill their personal potential and as social beings who seek to be accepted and successful within their community.

Definition

Self-concept or self identity refers to the understanding a sentient being has of itself, as can be expressed in terms of self-assessments that involve persistent attributes. It presupposes but can be distinguished from mere self-consciousness, which is an awareness of one's self. Generally, self-concept embodies the answer to the question, "Who am I?"[1]

The self-concept is different from self-consciousness, which is an awareness or preoccupation with one's self. Self-consciousness is often associated with shyness and embarrassment, in which case a lack of pride and low self-esteem can result.

The self-concept is also distinguishable from self-awareness, which is the extent to which self-knowledge is defined, consistent, and currently applicable to one's attitudes and dispositions. To have a fully developed self-concept (and one that is based in reality), a person must have at least some level of self-awareness.[2] The self-assessment "I am tired" would normally not be considered part of someone's self-concept, since the attribute of being tired is normally transient. "I am lazy," however, might well be a self-assessment that contributes to someone's self-concept. This requirement of persistence is relative, however, and refers to the being's subjective judgement: it does not imply immutability, and a person's self-concept will generally evolve with time.

Self-concept is made up of one's self-schemas, and interacts with self-esteem, self-knowledge, and the social self to form the self as a whole. It includes the past, present, and future selves, where future selves (or possible selves) represent individuals' ideas of what they might become, what they would like to become, or what they are afraid of becoming. Possible selves may function as incentives for certain behavior.[1]

Self-concept differs from self-esteem: self-concept is a cognitive or descriptive component of one's self (such as "I am a fast runner"), while self-esteem is evaluative and opinionated (such as "I feel good about being a fast runner").

Components of the self-concept include physical, psychological, and social attributes, which can be influenced by the individual's attitudes, habits, beliefs and ideas.

History

Early Greek philosophers theorized about the non-physical aspect of a person, the soul, which they viewed as the essential aspect of the self. A milestone in human reflection about the non-physical inner self came in 1644, when René Descartes wrote Principles of Philosophy. Descartes proposed that doubt was a principal tool of disciplined inquiry, yet he could not doubt that he doubted. He reasoned that if he doubted, he was thinking, and therefore he must exist. Thus existence depended upon perception.[3]

A second milestone in the development of self-concept theory was the writing of Sigmund Freud who introduced a new understanding of the importance of internal mental processes.[4] While Freud and many of his followers hesitated to make self-concept a primary psychological unit in their theories, Freud's daughter Anna gave central importance to ego development and self-interpretation.[5]

Psychologists Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow had major influence in popularizing the idea of self-concept in the twentieth century. By far the most influential and eloquent voice in self-concept theory was that of Carl Rogers who introduced an entire system of helping built around the importance of the self.[6] In Rogers' view, the self is the central ingredient in human personality and personal adjustment. Rogers described the self as a social product, developing out of interpersonal relationships and striving for consistency. He maintained that there is a basic human need for positive regard both from others and from oneself. He also believed that in every person there is a tendency towards self-actualization and development so long as this is permitted and encouraged by an inviting environment.[7]

Abraham Maslow developed the concept of self-actualization from his hierarchy of needs theory. In this theory, he explained the process it takes for a person to achieve self-actualization. He argued that for an individual to reach the "higher level growth needs," they must first accomplish "lower deficit needs." Once the "deficiency needs" have been achieved, the highest one being the need for self-esteem, the person's goal is to accomplish the next step, which is the "being needs." Maslow noticed that once individuals reach this level, they tend to "grow as a person" and reach self-actualization; the intrinsic growth of what is already in the person, in other words it is the realization of the person's full potential, their ultimate conception of their self. [8]

Self-concept is ultimately understood as the sum total of a person's knowledge and understanding of his or her self. What then, constitutes this "self"?

Self in philosophy

In philosophy, self is broadly defined as the essential qualities that make a person distinct from all others. There have been a number of different approaches to defining what these qualities are. This self is the agent responsible for the thoughts and actions of an individual to which they are ascribed. It is a substance, which therefore endures through time; thus, the thoughts and actions at different moments of time may pertain to the same self.

Ancient Greek philosophers

The ancient Greek philosophers viewed the soul as the essential self.

Plato, drawing on the words of his teacher Socrates, considered the soul as the essence of a person, which is an incorporeal, eternal occupant of our being. For Plato, the soul comprises three parts, each having a function in a balanced and peaceful life:

- the logos (superego, mind, nous, or reason). The logos corresponds to the charioteer, directing the balanced horses of appetite and spirit. It allows for logic to prevail, and for the optimization of balance

- the thymos (emotion, ego, or spiritedness). The thymos comprises our emotional motive (ego), that which drives us to acts of bravery and glory. If left unchecked, it leads to hubris—the most fatal of all flaws in the Greek view.

- the pathos (appetitive, id, or carnal). The pathos equates to the appetite (id) that drives humankind to seek out its basic bodily needs. When the passion controls us, it drives us to hedonism in all forms. In the Ancient Greek view, this is the basal and most feral state.

Aristotle, following Plato, defined the soul as the core essence of a being, but argued against its having a separate existence. For instance, if a knife had a soul, the act of cutting would be that soul, because 'cutting' is the essence of what it is to be a knife. Unlike Plato and the religious traditions, Aristotle did not consider the soul as some kind of separate, ghostly occupant of the body (just as we cannot separate the activity of cutting from the knife). As the soul, in Aristotle's view, is an activity of the body, it cannot be immortal (when a knife is destroyed, the cutting stops).[9] More precisely, the soul is the "first activity" of a living body. This is a state, or a potential for actual, or 'second,' activity. "The axe has an edge for cutting" was, for Aristotle, analogous to "humans have bodies for rational activity," and the potential for rational activity thus constituted the essence of a human soul.

Avicenna and Descartes

While he was imprisoned in a castle, Avicenna wrote his famous "Floating Man" thought experiment to demonstrate human self-awareness and the substantiality of the soul. His "Floating Man" tells its readers to imagine themselves suspended in the air, isolated from all sensations, which includes no sensory contact with even their own bodies. He argues that, in this scenario, one would still have self-consciousness. He thus concludes that the idea of the self is not logically dependent on any physical thing, and that the soul should not be seen in relative terms, but as a primary given, a substance.

This argument was later refined and simplified by René Descartes in epistemic terms when he stated: "I can abstract from the supposition of all external things, but not from the supposition of my own consciousness."[10]

Hume

David Hume pointed out that we tend to think that we are the same person we were five years ago. Though we have changed in many respects, the same person appears present as was present then. We might start thinking about which features can be changed without changing the underlying self. Hume, however, denies that there is a distinction between the various features of a person and the mysterious self that supposedly bears those features. After all, Hume pointed out, when you start introspecting, you notice a bunch of thoughts and feelings and perceptions and such, but you never perceive any substance you could call "the self." So as far as we can tell, Hume concludes, there is nothing to the self over and above a big, fleeting bundle of perceptions.

Note in particular that, on Hume's view, these perceptions do not belong to anything. Rather, Hume compares the soul to a commonwealth, which retains its identity not by virtue of some enduring core substance, but by being composed of many different, related, and yet constantly changing elements. The question of personal identity then becomes a matter of characterizing the loose cohesion of one's personal experience.

Others

Lao Zi (also Lao Tzu) in his Dao De Jing (also Tao Te Ching) says:

Knowing others is wisdom. Knowing the self is enlightenment. Mastering others requires force. Mastering the self requires strength.

In spirituality, and especially nondual, mystical and eastern meditative traditions, the human being is often conceived as being in the illusion of individual existence, and separateness from other aspects of creation. This "sense of doership" or sense of individual existence is that part which believes it is the human being, and believes it must fight for itself in the world, is ultimately unaware and unconscious of its own true nature. The ego is often associated with mind and the sense of time, which compulsively thinks in order to be assured of its future existence, rather than simply knowing its own self and the present.

The goal of many spiritual traditions involves the dissolving of the ego, allowing self-knowledge of one's own true nature to become experienced and enacted in the world. This is variously known as Enlightenment, Nirvana, Presence, and the "Here and Now."

The Indian Hindu sage, Ramana Maharshi, espoused certain concepts about the self in the book Nan Yar (Who am I):

- Since all trace of the 'I' does not exist, alone is Self.

- Self itself is the world; Self itself is 'I'; Self itself is God; all is the Supreme Self (siva swarupam)

On the other hand, the very concept of the self has been disputed by some prominent philosophers. The Buddha in particular disagreed with the concept of an enduring self.

Self in psychology

The self is a key construct in several schools of psychology, broadly referring to the cognitive representation of one's identity. The earliest formulation of the self in modern psychology stems from the distinction between the self as I, the subjective knower, and the self as Me, the object that is known.[11] More recent views of the self in psychology diverge greatly from this early conception, positioning the self as playing an integral part in human motivation, cognition, affect, and social identity.[12] The development of views of the self greatly impact the importance of self-concept.

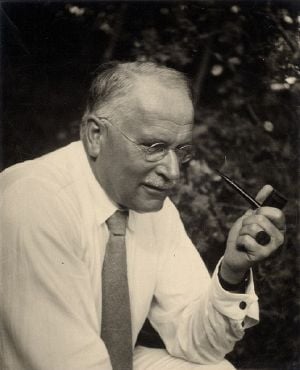

Jung's Self

In Jungian theory, the Self is one of the archetypes. According to Jung, the self is the most important archetype. It is called the "midpoint of the personality," a center between consciousness and the unconscious, the ultimate unity of the personality. It signifies the harmony and balance between the various opposing qualities that make up the psyche.

Symbols of the self are often manifested in geometrical forms such as circles, a cross, (mandalas), or by the quaternity (a figure with four parts). Prominent human figures which represent the self are the Buddha or Christ. The symbols of the self can be anything that the ego takes to be a greater totality than itself. Thus many symbols fall short of expressing the self in its fullest development.

What distinguishes Jungian psychology is the idea that there are two centers of the personality. The ego is the center of consciousness, whereas the Self is the center of the total personality, which includes consciousness, the unconscious, and the ego. The Self is both the whole and the center. While the ego is a self-contained little circle off the center contained within the whole, the Self can be understood as the greater circle.[13]

Winnicott's selves

English pediatrician and psychoanalyst, Donald Winnicott, distinguished what he called the "true self" from the "false self" in the human personality. He used "true self" to denote a sense of self based on spontaneous authentic experience and a feeling of being alive. He considered the true self to be based on the individual's sense of being, not doing, something which was rooted in the experiencing body.[14] As he memorably put it to Harry Guntrip, "You know about 'being active,' but not about 'just growing, just breathing'."[15] it was the latter qualities that went to form the true self.

Nevertheless, Winnicott valued the role of the false self in the human personality, regarding it in fact as a necessary form of defensive organization – a kind of caretaker, a survival suit behind the protection of which the true self was able to continue to exist.[14] Five levels of false self organization were identified by Winnicott, running along a kind of continuum.[16]

- In the most severe instance, the false self completely replaces and ousts the true self, leaving the latter a mere possibility.[16]

- Less severely, the false self protects the true self, which remains unactualized - for Winnicott a clear example of a clinical condition organized for the positive goal of preserving the individual in spite of abnormal environmental conditions of the environment.

- Closer to health, the false self supports the individual's search for conditions that will allow the true self to recover its well-being - its own identity.

- Even closer to health, we find the false self "... established on the basis of identifications."[17]

- Finally, in a healthy person, the false self is composed of that which facilitates social behavior, the manners and courtesy that allows for a smooth social life, with emotions expressed in socially acceptable forms.[16]

For Winnicott, one of the most important and precarious stages of development was in the first three years of life, when an infant grows into a child with an increasingly separate sense of self in relation to a larger world of other people. In health, the child learns to bring his or her spontaneous, real self into play with others; in a false self disorder, the child has found it unsafe or impossible to do so, and instead feels compelled to hide the true self from other people, and pretend to be whatever they want instead, presenting only their false self.[14]

Rogers on self and self-concept

According to Carl Rogers, who, along with Abraham Maslow, founded the humanistic approach to psychology, believed that people develop their self-concept through relationships with others and also in relation to themselves.

Rogers described the development of the self-concept in terms of progress from an undifferentiated self to being fully differentiated:

Self Concept ... the organized consistent conceptual gestalt composed of perceptions of the characteristics of 'I' or 'me' and the perceptions of the relationships of the 'I' or 'me' to others and to various aspects of life, together with the values attached to these perceptions. It is a gestalt which is available to awareness though not necessarily in awareness. It is a fluid and changing gestalt, a process, but at any given moment it is a specific entity.[18]

In the development of the self-concept, Rogers saw conditional and unconditional positive regard as key. In other words, an encouraging environment helps people towards this development. Those raised in an environment of unconditional positive regard have the opportunity to fully actualize themselves. Those raised in an environment of conditional positive regard feel worthy only if they match conditions that others have laid down for them.

Rogers agreed with Kierkegaard's statement that "the most common despair is to be in despair at not choosing, or willing, to be oneself; but that the deepest form of despair is to choose 'to be another than himself.' On the other hand, 'to will to be that self which one truly is, is indeed the opposite of despair'."[6]

Turner's Self-categorization

British social psychologist John Turner and colleagues developed self-categorization theory in which the self is an outcome of cognitive processes and an interaction between the person and the social context. He argued that the self-concept consists of at least two "levels": a personal identity and a social one. In other words, one's self-evaluation relies on both self-perceptions and on how others perceive them.[19]

Self-evaluation develops as the child integrates their social identity, based on assessment of their position among peers, into their own self-concept. By around age five, particularly when the child has experienced a school situation outside of their immediate family, acceptance from peers begins to affect children's self-concept, influencing their behavior and impacting their academic success.

Self in sociology

In sociology, the self refers to an individual person from the perspective of that person. It is the individual's conception of himself or herself, and the underlying capacity of the person's mind or intellect which formed that conception (one's "true self").

This understanding of one's self is influenced by the social environment. Charles Horton Cooley used the metaphor of a mirror to describe this process, as one's self, the "looking glass self," is reflected back in they way others respond to them, their appearance, their actions, and what they say. We then use their reactions to make self-judgments, either positive or negative depending on the type of response from others.[20]

According to Cooley, development of this "looking glass self"[21] involves three steps:

- To begin, people picture their appearance of themselves, traits and personalities.

- They then use the reactions of others to interpret how others visualize them.

- Finally, they develop their own self-concept, based on their interpretations. Their self-concept can be enhanced or diminished by their conclusions.

George Herbert Mead also focused on social interaction as important for developing a sense of self. Following William James, Mead found it convenient to express the dual and reflexive nature of the self through the concepts of the "I" and the "me," where the "I" is the subjective and active phase of the self, and the "me" is the objective and passive phase. Understood as a combination of the "I" and the "me," Mead’s self proved to be noticeably entwined within a sociological existence: "The self is essentially a social process going on with these two distinguishable phases."[22] Thus, Mead's view of the self is of that self emerging through social acts involving interaction with other individuals.

The key to living well is to find ways to give expression to the “I” with the approval of the “me”. In other words, find out how to be creative and do what you care about within the guidelines of society. A child, who has been told not to do something, may be found saying “no” to himself. Gradually, the child comes to understand how society at large comes to view actions, both good and bad. In this way, cultural expectations become part of the judgment of self.[20]

Developing one's self-concept

When self-concept development begins is a matter of debate. Self-concept involves beliefs about general personal identity or personal attributes, such as age, physical characteristics, behavior, and skills. Accurate understanding of these attributes develops from early childhood to late childhood, and continues to change in adulthood. A more realistic sense of self is present in middle and late childhood than in early childhood, which can be attributed to greater experience in comparing their own performance with that of others, and to greater cognitive flexibility. Children in middle and late childhood are also able to include other peoples’ appraisals of them into their self-concept.[20]

It has been reported that gender stereotypes and expectations set by parents for their children affect children's understanding of themselves as early as three years of age. However, at this developmental stage, children have a very broad sense of self; typically, they use words such as "big" or "nice" to describe themselves to others.[23]

Others suggest that self-concept develops later, in middle childhood, alongside the development of self-control.[24] At this point, children are developmentally prepared to interpret their own feelings and abilities, as well as receive and consider feedback from peers, teachers, and family. In adolescence, the self-concept undergoes a time of significant change, showing a "U"-shaped curve, in which general self-concept decreases in early adolescence, followed by an increase in later adolescence.[25] Additionally, teens begin to evaluate their abilities on a continuum, as opposed to the "yes/no" evaluation of children. For example, while children might evaluate themselves as "smart," teens might evaluate themselves as "not the smartest, but smarter than average."

Relationships affect people's self-concept, and older children and young adults develop not only different types of relationships but also with a broader range of people. Thus their self-concept develops as these relationships develop.[26]

Despite differing opinions about the onset of self-concept development, there is agreement on the importance of one's self-concept, which influences people's behaviors and cognitive and emotional outcomes including (but not limited to) academic achievement, levels of happiness, anxiety, social integration, self-esteem, and life-satisfaction.

Academic

Academic self-concept refers to the personal beliefs about their academic abilities or skills. Some research suggests that it begins developing from ages three to five due to influence from parents and early educators. By age ten or eleven, children assess their academic abilities by comparing themselves to their peers.[27]

Some researchers suggest that to raise academic self-concept, parents and teachers need to provide children with specific feedback that focuses on their particular skills or abilities.[28] Others suggest that learning opportunities should be conducted in groups (both mixed-ability and like-ability) that downplay social comparison, as too much of either type of grouping can have adverse effects on children's academic self-concept and the way they view themselves in relation to their peers.[29]

Physical

Physical self-concept is the individual's perception of themselves in areas of physical ability and appearance. Physical ability includes concepts such as physical strength and endurance, while appearance refers to attractiveness and body image.[30] An important factor of physical self-concept development is participation in physical activities.

Adolescents experience significant changes in general physical self-concept at the onset of puberty, about eleven years old for girls and about 15 years old for boys. The bodily changes during puberty, in conjunction with the various psychological changes, makes adolescence especially significant for the development of physical self-concept.[31]

Gender identity

A person's gender identity is a sense of one's own gender. These ideas typically form in young children, when they are able to communicate.[32] After this stage, some postulate that gender identity has already been formed, although others consider non-gendered identities more salient during that young of an age.

According Kohlberg, achieving gender constancy is a critical milestone in gender development. He outlined three developmental stages that children achieve in order to have gender constancy: The first stage, gender identity, is the child’s basic awareness that they are either a boy or girl. The second stage, gender stability, is the recognition that gender identity does not change over time; boys become men and girls become women. The third stage, gender consistency, represents the achievement of gender constancy and is the understanding that gender is not changed by transformations in gender-typed appearances, activities, roles, and traits. In other words, once children achieve gender constancy, at about age 6–7 years, they understand that they are either a girl or a boy (gender identity), that they will grow up to be an adult of the same gender (a woman or a man) (gender stability), and that their gender will not be changed if they do things such as put on opposite sex-typed clothes or participate in sports or other activities generally favored by those of the opposite sex (gender consistency). [33]

Both biological and social factors may influence gender identities, such as a sense of individuality, identities of place, as well as experiences of gender stereotyping.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 David G. Myers, Social Psychology (10th ed.) (New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2009, ISBN 978-0073370668).

- ↑ Courtney E. Ackerman, What is Self-Concept Theory? A Psychologist Explains Positive Psychology. Retrieved May 18, 2023.

- ↑ René Descartes, The Principles of Philosophy (Latin: Principia Philosophiae, 1644; French Les Principes de la Philosophie, 1647) John Veitch (trans.) (Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2004, ISBN 1419178830).

- ↑ Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams (Die Traumdeutung, 1900) James Strachey (trans.) (Basic Books, 2010 (original 1955), ISBN 978-0465019779).

- ↑ Anna Freud, The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defence (Routledge, 1992 (original 1936), ISBN 978-1855750388).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Carl R. Rogers, On Becoming a Person (Houghton Mifflin, 1961, ISBN 0395081343).

- ↑ William Watson Purkey and John J. Schmidt, The Inviting Relationship: An Expanded Perspective for Professional Counseling (Pearson, 1987, ISBN 978-0135055380).

- ↑ Abraham H. Maslow, Toward a Psychology of Being (New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, 1998, ISBN 978-0471293095).

- ↑ There has been debate about Aristotle's views regarding the immortality of the human soul; however, Aristotle makes it clear towards the end of his De Anima that he does believe that the intellect, which he considers to be a part of the soul, is eternal and separable from the body.

- ↑ Seyyed Hossein Nasr and Oliver Leaman (eds.), History of Islamic Philosophy (Routledge, 1996, ISBN 978-0415131599).

- ↑ William James, The Principles of Psychology, Vol.1. (Dover Publications, 1950 (original 1890), ISBN 978-0486203812).

- ↑ Constantine Sedikides and Steven J. Spencer (eds.), The Self (New York: Psychology Press, 2007, ISBN 978-1841694399).

- ↑ Connie Zweig and Jeremiah Abrams (eds.), Meeting the Shadow: The Hidden Power of the Dark Side of Human Nature (Los Angeles, CA: J.P. Tarcher, 1991, ISBN 978-0874776188).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Josephine Klein, Our Need for Others and its Roots in Infancy (Routledge, 2017, ISBN 978-1138410367).

- ↑ Michael Parsons, The Dove that Return, the Dove that Vanishes: Paradox and Creativity in Psychoanalysis (Routledge, 2000, ISBN 978-0415211826), 82.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Derek Hook, Jacki Watts, and Kate Cockcroft, Developmental Psychology (University of Cape Town Press, 2004, ISBN 978-1919713687).

- ↑ Donald W. Winnicott, The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment (Routledge, 1990 (original 1965), ISBN 978-0946439843).

- ↑ Carl Rogers, "A theory of therapy, personality relationships as developed in the client-centered framework" in Sigmund Koch (ed.), Psychology: A study of a science. Vol. 3: Formulations of the person and the social context (New York: McGraw Hill, 1959).

- ↑ William G. Austin and Stephen Worchel, The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations (Brooks Cole Publishing, 1979, ISBN 978-0818502781).

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Marie Parnes and Maria Pagano, Development of the Self and Moral Development Infant and Child Development: From Conception Through Late Childhood (Press Books, 2022). Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- ↑ Charles Horton Cooley, Human Nature and the Social Order (Andesite Press, 2017 (original 1902), ISBN 1375906550).

- ↑ George Herbert Mead, On Social Psychology (University of Chicago Press, 1964, ISBN 0226516652).

- ↑ Patricia C. Broderick and Pamela Blewitt, The Life Span: Human development for helping professionals (Pearson, 2014, ISBN 978-0132942881).

- ↑ W. Andrew Collins, Development During Middle Childhood: The Years From Six to Twelve (National Academies Press, 1984, ISBN 978-0309078290).

- ↑ Jennifer Shapka and Daniel Keating, "Structure and Change in Self-Concept during Adolescence" Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science 37(2) (April 2005): 83–96.

- ↑ Brent A. Mattingly, Kevin P. McIntyre, and Gary W. Lewandowski Jr. (eds.), Interpersonal Relationships and the Self-Concept (Springer, 2020, ISBN 978-3030437466).

- ↑ Christine M. Rubie-Davies, "Teacher Expectations and Student Self-Perceptions: Exploring Relationships" Psychology in the Schools 43(5) (May 2006): 537–552.

- ↑ Rhonda G. Craven and Herbert W. Marsh "Effects of internally focused feedback and attributional feedback on enhancement of academic self-concept" Journal of Educational Psychology 83 (1)(1991): 17–27.

- ↑ Ulrich Trautwein, Oliver Lüdtke, Herbert W. Marsh, and Gabriel Nagy "Within-school social comparison: How students perceive the standing of their class predicts academic self-concept" Journal of Educational Psychology 101(4) (2009): 853–866.

- ↑ Emine Çaglar, "Similarities and Differences in Physical Self-Concept of Males and Females during Late Adolescence and Early Adulthood" Adolescence 44(174) (Summer 2009):407–419.

- ↑ Anne Klomsten, Einar Skaalvik, and Geir Espnes, "Physical Self-Concept and Sports: Do Gender Differences Still Exist?" Sex Roles 50 (January 2004): 119–127.

- ↑ Danuta Bukatko and Marvin W. Daehler, Child Development: A Thematic Approach (Wadsworth Publishing, 2003, ISBN 978-0618333387).

- ↑ Janette B. Benson (ed.), Encyclopedia of Infant and Early Childhood Development (Elsevier, 2020, ISBN 978-0128165126).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Austin, William G., and Stephen Worchel. The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Brooks Cole Publishing, 1979. ISBN 978-0818502781

- Benson Janette B. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Infant and Early Childhood Development. Elsevier, 2020,. ISBN 978-0128165126

- Broderick, Patricia C., and Pamela Blewitt. The Life Span: Human development for helping professionals. Pearson, 2014. ISBN 978-0132942881

- Bukatko, Danuta, and Marvin W. Daehler. Child Development: A Thematic Approach. Wadsworth Publishing, 2003. ISBN 978-0618333387

- Collins, W. Andrew. Development During Middle Childhood: The Years From Six to Twelve. National Academies Press, 1984. ISBN 978-0309078290

- Cooley, Charles Horton. Human Nature and the Social Order. Andesite Press, 2017 (original 1902). ISBN 1375906550

- Descartes, René. The Principles of Philosophy (Latin: Principia Philosophiae, 1644; French Les Principes de la Philosophie, 1647) John Veitch (trans.). Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2004. ISBN 1419178830

- Freud, Anna. The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defence. Routledge, 1992 (original 1936). ISBN 978-1855750388

- Freud, Sigmund. The Interpretation of Dreams (Die Traumdeutung, 1900) James Strachey (trans.). Basic Books, 2010 (original 1955). ISBN 978-0465019779

- Hook, Derek, Jacki Watts, and Kate Cockcroft. Developmental Psychology. University of Cape Town Press, 2004. ISBN 978-1919713687

- James, William. The Principles of Psychology, Vol.1. Dover Publications, 1950 (original 1890). ISBN 978-0486203812

- Klein, Josephine. Our Need for Others and its Roots in Infancy. Routledge, 2017. ISBN 978-1138410367

- Koch, Sigmund (ed.). Psychology: A study of a science. Vol. 3: Formulations of the person and the social context. New York: McGraw Hill, 1959. ASIN B000H40D60

- Maslow, Abraham H. Toward a Psychology of Being. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, 1998. ISBN 978-0471293095

- Mattingly, Brent A., Kevin P. McIntyre, and Gary W. Lewandowski Jr. (eds.). Interpersonal Relationships and the Self-Concept. Springer, 2020. ISBN 978-3030437466

- Mead, George Herbert. On Social Psychology. University of Chicago Press, 1964. ISBN 0226516652

- Myers, David G. Social Psychology (10th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Higher Education, 2009. ISBN 978-0073370668

- Nasr, Seyyed Hossein, and Oliver Leaman (eds.). History of Islamic Philosophy. Routledge, 1996. ISBN 978-0415131599

- Parnes, Marie, and Maria Pagano. [Infant and Child Development: From Conception Through Late Childhood] Press Books, 2022. Retrieved May 21, 2023.

- Parsons, Michael. The Dove that Return, the Dove that Vanishes: Paradox and Creativity in Psychoanalysis. Routledge, 2000. ISBN 978-0415211826

- Purkey, William Watson, and John J. Schmidt. The Inviting Relationship: An Expanded Perspective for Professional Counseling. Pearson, 1987. ISBN 978-0135055380

- Rogers, Carl R. On Becoming a Person. Houghton Mifflin, 1961. ISBN 0395081343

- Sedikides, Constantine, and Steven J. Spencer (eds.). The Self. New York: Psychology Press, 2007., ISBN 978-1841694399

- Winnicott, Donald W. The Maturational Processes and the Facilitating Environment. Routledge, 1990 (original 1965). ISBN 978-0946439843

- Zweig, Connie, and Jeremiah Abrams (eds.). Meeting the Shadow: The Hidden Power of the Dark Side of Human Nature. Los Angeles, CA: J.P. Tarcher, 1991. ISBN 978-0874776188

External links

All links retrieved May 22, 2023.

- What Is Self-Concept? Very Well Mind

- What is Self-Concept Theory? A Psychologist Explains Positive Psychology

- Self-Concept In Psychology: Definition, Development, Examples Simply Psychology

- The Makeup and Theories of Self Concept Psych Central

- What Is Self-Concept in Psychology? ThoughtCo

- What Is Self-Concept? (A Definition) Berkeley Well-Being Institute

- Self-Knowledge Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Self_concept history

- Self_(psychology) history

- Self_(sociology) history

- Self_(philosophy) history

- Self_(Jung) history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.