Abraham Maslow

Abraham Maslow (April 1, 1908 – June 8, 1970) was an American psychologist who helped found the school of transpersonal psychology. He broke away from the prevailing mechanistic materialist paradigm of behaviorism and developed the view that the human needs for security, love, belonging, self-esteem, and self-actualization were more important than physiological needs for food, sleep, and sex. He developed a theory of a hierarchy of human needs, of which the highest were the need for "self-actualization" through creative and productive living.

His humanistic model allowed psychologists and students of psychology to appreciate the spiritual dimension of human nature.

Biography

Born in Brooklyn, New York, Abraham Maslow was the first of seven children of Jewish immigrants from Russia. His parents were uneducated, but they insisted that he study law. At first, Abraham acceded to their wishes and enrolled in the City College of New York (CCNY). However, after three semesters, he transferred to Cornell University then back to CCNY.

At twenty years of age he married his childhood sweetheart, Bertha Goodman, an artist, on December 31, 1928. In The Last Interview of Abraham Maslow, he said "Life didn't really start for me until I got married." They later parented two daughters, Ann and Ellen. With his wife, he moved to Wisconsin to attend the University of Wisconsin from which he received his B.A. (1930), his M.A. (1931), and his Ph.D. degrees (1934) in psychology. While in Wisconsin, Maslow studied with Harry Harlow, who was known for his studies of rhesus monkeys and attachment behavior.

A year after graduation, Maslow returned to New York to work with Edward L. Thorndike at Columbia University. Maslow began teaching full time at Brooklyn College. During this time he met many leading European psychologists, including Alfred Adler and Erich Fromm. In 1951, Maslow became the chairman of the psychology department at Brandeis University, where he began his theoretical work. There, he met Kurt Goldstein, who introduced him to the idea of self-actualization.

Later he retired to California, where he died of a heart attack in 1970 after years of ill health.

Hierarchy of human needs

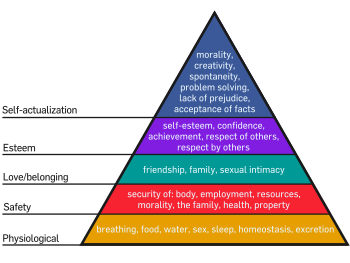

Maslow first proposed his theory of a "hierarchy of needs" in his 1943 paper A Theory of Human Motivation. His theory contends that as humans meet "basic needs," they seek to satisfy successively "higher needs" that occupy a set hierarchy. Maslow studied exemplary people such as Albert Einstein, Jane Addams, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Frederick Douglass, rather than mentally ill or neurotic people, writing that "the study of crippled, stunted, immature, and unhealthy specimens can yield only a crippled psychology and a crippled philosophy." (Motivation and Personality, 1987)

Maslow's hierarchy of needs is often depicted as a pyramid consisting of five levels: the four lower levels are grouped together as "deficiency" needs and are associated with physiological needs, while the top level is termed "being" or "growth" needs and are associated with psychological needs. The deficiency needs are the necessities of life which must be met, while the "growth" needs are desires that continually shape our behavior.

Maslow suggested that human needs are arranged in hierarchies of pre-potency, which means that the appearance of one need usually rests on the prior satisfaction of another, more pre-potent need. The basic concept is that the higher needs in this hierarchy only come into focus once all the needs that are lower down in the pyramid are satisfied. A person experiencing extreme lack of food, safety, love, and esteem would most probably hunger for food more strongly than for anything else.

Deficiency needs

The deficiency needs (also termed 'D-needs' by Maslow) are physiological, safety, love/belonging, and esteem needs:

Physiological needs

The physiological needs of the organism, those enabling homeostasis, take first precedence. These consist mainly of:

- the need to breathe

- the need to drink and eat

- the need to dispose of bodily waste material

- the need for sleep

- the need to regulate bodily temperature

- the need for protection from microbial aggressions (hygiene)

Maslow also placed sexual activity in this category, as well as bodily comfort, activity, exercise, etc.

When physiological needs are not met, they take the highest priority. As a result of the dominance of physiological needs, an individual will deprioritize all other desires and capacities. Physiological needs can control thoughts and behaviors, and can cause people to feel sickness, pain, and discomfort.

Safety needs

When the physiological needs are met, the need for safety will emerge. The need for safety and security ranks above all other desires. Sometimes the desire for safety outweighs the requirement to satisfy physiological needs.

Safety needs include:

- Security of employment

- Security of revenues and resources

- Physical security

- Moral and physiological security

- Familial security

- Security of health

Maslow noted that a properly-functioning society tends to provide a degree of security to its members.

Love/Belonging needs

After physiological and safety needs are fulfilled, the third layer consists of social needs. These involve emotionally-based relationships in general, such as friendship, a spouse and family, affectionate relationships, and a sense of community. People want to be accepted and to belong to groups, whether it be clubs, work groups, religious groups, family, gangs, etc. They need to feel loved by others and to be accepted by them. People also have a constant desire to feel needed. According to Maslow, in the absence of these elements, people become increasingly susceptible to loneliness, social anxiety and depression.

Esteem needs

The fourth layer consists of needs related to self-esteem. These include the need to be respected, to have self-respect, and to respect others. Also included are the needs to engage oneself in order to gain recognition, and to take part in an activity which gives value to oneself, be it in a profession or hobby. Imbalances at this level can result in a low self-esteem and an inferiority complex, or, on the other hand, in an inflated sense of self and snobbishness.

Being needs

Though the deficiency needs may be seen as "basic," and can be met and neutralized (stop being motivators in one's life), "being" or "growth" needs (also termed "B-needs") are enduring motivations or drivers of behavior. These needs are self-actualization and self-transcendence.

Self-actualization

Self-actualization (a term originated by Kurt Goldstein) is the instinctual need of a human to make the most of their unique abilities. Maslow described it as follows:

- Self actualization is the intrinsic growth of what is already in the organism, or more accurately, of what the organism is (Psychological Review, 1949).

- A musician must make music, an artist must paint, and a poet must write, if he is to be ultimately at peace with himself. What a man can be, he must be. This is what we may call the need for self-actualization (Motivation and Personality, 1954).

Maslow wrote the following of self-actualizing people:

- They embrace the facts and realities of the world (including themselves) rather than denying or avoiding them.

- They are spontaneous in their ideas and actions.

- They are creative.

- They are interested in solving problems; this often includes the problems of others. Solving these problems is often a key focus in their lives.

- They feel a closeness to other people and generally appreciate life.

- They have a system of morality that is fully internalized and independent of external authority.

- They judge others without prejudice, in a way that can be termed "objective."

Maslow pointed out that these people had virtues, which he called B-Values:

Self-transcendence

Maslow also proposed that people who have reached self-actualization will sometimes experience a state he referred to as "transcendence," or "peak experience," in which they become aware of not only their own fullest potential, but the fullest potential of human beings at large. Peak experiences are sudden feelings of intense happiness and well-being, the feeling that one is aware of "ultimate truth" and the unity of all things. Accompanying these experiences is a heightened sense of control over the body and emotions, and a wider sense of awareness, as though one was standing upon a mountaintop. The experience fills the individual with wonder and awe. He feels one with the world and is pleased with it; he or she has seen the ultimate truth or the essence of all things.

Maslow described this transcendence and its characteristics in an essay in the posthumously published The Farther Reaches in Human Nature. He noted that this experience is not always transitory and/or momentary, but that certain individuals might have ready access to it and spend more time in this state. Not long before his death in 1970, Maslow defined the term "plateau experience" as a sort of continuing peak experience that is more voluntary, noetic, and cognitive. He made the point that such individuals experience not only ecstatic joy, but also profound "cosmic-sadness" at the ability of humans to foil chances of transcendence in their own lives and in the world at large.

Maslow believed that we should study and cultivate peak experiences as a way of providing a route to achieving personal growth, integration, and fulfillment. Individuals most likely to have peak experiences are self-actualized, mature, healthy, and self-fulfilled. However, all individuals are capable of peak experiences. Those who do not have them somehow repress or deny them. Peak experiences render therapeutic value as they foster a sense of being graced, release creative energies, reaffirm the worthiness of life, and change an individual's view of him or herself. Maslow cautioned against seeking such experiences for their own sake, echoing the advice of the mystics who have pointed out that the sacred exists in the ordinary. Maslow further believed that domestic and public violence, alcoholism, and drug abuse stem from spiritual emptiness, and that even one peak experience might be able to prevent, or at least abate, such problems. Maslow's ultimate conclusion, that the highest levels of self-actualization are transcendent in their nature, may be one of his most important contributions to the study of human behavior and motivation.

Viktor Frankl expressed the relationship between self-actualization and self-transcendence clearly in Man's Search for Meaning. He wrote:

- The true meaning of life is to be found in the world rather than within man or his own psyche, as though it were a closed system....Human experience is essentially self-transcendence rather than self-actualization. Self-actualization is not a possible aim at all, for the simple reason that the more a man would strive for it, the more he would miss it.... In other words, self-actualization cannot be attained if it is made an end in itself, but only as a side effect of self-transcendence (p.175).

Ken Wilber, author of Integral Psychology, later clarified a peak experience as being a state that could occur at any stage of development and that "the way in which those states or realms are experienced and interpreted depends to some degree on the stage of development of the person having the peak experience." Wilber was in agreement with Maslow about the positive values of peak experiences saying, "In order for higher development to occur, those temporary states must become permanent traits."

Criticisms of Maslow's work

While Maslow's theory was regarded by many as an improvement over previous theories of personality and motivation, it had its detractors. For example, in their extensive review of research that is dependent on Maslow's theory, Wabha and Bridwell (1976) found little evidence for the ranking of needs that Maslow described, or even for the existence of a definite hierarchy at all. Some have argued that Maslow was unconsciously naive about elitist elements in his theories. As one critic poses, "What real individuals, living in what real societies, working at what real jobs, and earning what real income have any chance at all of becoming self-actualizers?"

Some behaviorists believe that self actualization is a difficult concept for researchers to operationalize, and this in turn makes it difficult to test Maslow's theory. Even if self-actualization is a useful concept, some contend that there is no proof that every individual has this capacity or even the goal to achieve it. On the other hand, the following examples are cited as ways people do self-actualize:

- Viktor Frankl's book Man's Search for Meaning describes his psychotherapeutic method (logotherapy) of finding purpose in life.

- Albert Einstein was drawn toward the sense of mystery in life (Pais 1983).

- Many individuals, such as Mother Teresa, M. K Gandhi, Martin Luther King, Jr. and many others, seek to perform good works on a path to self-actualization.

Transcendence has been discounted by secular psychologists because they feel it belongs to the domain of religious belief. Maslow himself believed that science and religion were both too narrowly conceived, too dichotomized, and too separated from each other. Non-peakers, as he would call them, characteristically think in logical, rational terms and look down on extreme spirituality as "insanity" (Maslow, 1964/1994, p.22) because it entails a loss of control and deviation from what is socially acceptable. They may even try to avoid such experiences because they are not materially productive – they "earn no money, bake no bread, and chop no wood" (Maslow, 1964/1994, p.23). Other non-peakers have the problem of immaturity in spiritual matters, and, hence, tend to view holy rituals and events in their most crude, external form, not appreciating them for any underlying spiritual implications. In Religions, Values, and Peak-Experiences (1964) and The Farther Reaches of Human Nature (1971), Maslow argued that the study of peak experiences, which occur in both religious and nonreligious forms, provides a way of closing the unproductive gap between religion and science.

Legacy

In 1967, Abraham Maslow was named humanist of the year by the American Humanist Association. That same year he was elected president of the American Psychological Association. Maslow played a major role in organizing both the Journal of Humanistic Psychology and the Journal of Transpersonal Psychology. In 1969, Abraham Maslow, Stanislav Grof and Anthony Sutich were the initiators behind the publication of the first issue of the Journal of Transpersonal Psychology.

This outgrowth of Maslow's work, Transpersonal psychology, is one in which the focus is on the spiritual well-being of individuals. Transpersonal psychologists seek to blend Eastern religion (Buddhism, Hinduism, and others) and Western (Christian, Jewish or Moslem) mysticism to create a form of modern psychology. Frequently, the transpersonal psychologist rejects psychology's adoption of various scientific methods used in the natural sciences.

At the time of his death, Maslow was a resident fellow at the Laughlin Foundation in California. Like the early humanists, he emphasized the inherent goodness in people. Maslow viewed humans as exercising a high degree of conscious control over their lives and as having a high resistance to pressures from the environment. In this sense, he was one of the early pioneers of the "resiliency research" now used to develop prevention strategies in the field of Positive Youth Development and the strengths-based approach of many schools of social work today. Maslow was probably the first to study "healthy self-actualizers" rather than to focus on "abnormal" psychology as was the norm for his times.

The Esalen Institute, one of the best-known centers for practicing group-encounter psychotherapy, mind-body modalities, and spiritual healing, continues to make use of Maslow's ideas.

Maslow's last interview in Psychology Today was a major opportunity to outline his "comprehensive human psychology" and the best way to actualize it. At 60, he knew that time permitted him only to plant seeds (in his own metaphor) of research and theory and hope that later generations would live to see the flowering of human betterment. Perhaps most prophetic at a time of global unrest (soon after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941) is Maslow's stirring vision of "building a psychology for the peace table." It was his hope that through psychological research, we might learn how to unify peoples of differing racial and ethnic origins, and thereby create a world of peace. In the interview he said:

I had a vision of a peace table, with people sitting around it, talking about human nature and hatred, war and peace, and brotherhood. I was too old to go into the army. It was at that moment I realized that the rest of my life must be devoted to discovering a psychology for the peace table. That moment changed my whole life. Since then, I've devoted myself to developing a theory of human nature that could be tested by experiment and research. I wanted to prove that humans are capable of something grander than war, prejudice, and hatred. I wanted to make science consider all the people: the best specimen of mankind I could find. I found that many of them reported having something like mystical experiences.

Publications

- Maslow, A. H. 1943. "A Theory of Human Motivation," Retrieved December 9, 2011. Originally published in Psychological Review 50: 370-396.

- Maslow, A. H. [1954] 1987. Motivation and Personality. New York, NY: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0060419875

- Maslow, A. H. [1964] 1994. Religions, Values, and Peak-Experiences, Penguin Arkana Books. ISBN 978-0140194876

- Maslow, A. H. 1965. Eupsychian Management. Richard D Irwin. ISBN 978-0870940569

- Maslow, A. H. [1968] 1998. Toward a Psychology of Being. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0471293095

- Maslow, A. H. [1971] 1994. The Farther Reaches of Human Nature. Penguin. ISBN 978-0140194708

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- DeCarvalho, Roy Jose. 1991. The Founders of Humanistic Psychology. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 027594008X

- Frankl, Viktor. 1985. Man's Search for Meaning. Washington Square Press. ISBN 0671646702

- Hoffman, Edward. 1988. The Right to be Human: A Biography of Abraham Maslow. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0874774616

- Hoffman, Edward. 1992. Overcoming Evil: An interview with Abraham Maslow, founder of humanistic psychology" Psychology Today 25(1). Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- Mook, D.G. 1987. Motivation: The Organization of Action. London: W.W. Norton & Company Ltd. ISBN 0393954749

- Pais, Abraham. 1983. Subtle Is the Lord: The Science and the Life of Albert Einstein. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195204384

- Wahba, Mahmoud A., and Lawrence G. Bridwell. 1976. "Maslow Reconsidered: A Review of Research on the Need Hierarchy Theory," Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 15(2): 212-240.

- Wilber, Ken. 2000. Integral Psychology: Consciousness, Spirit, Psychology, Therapy. Shambhala. ISBN 1570625549

External links

All links retrieved June 14, 2023.

- A Theory of Human Motivation Abraham Maslow's paper originally published in Psychological Review, 50 (1943): 370-396.

- Dr. C. George Boeree. Abraham Maslow 1908-1970

- Huitt, W. 2007. Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University.

- Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs and Need Levels

- Abraham Maslow (1904 - 1970)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.