Jane Addams

Jane Addams (September 6, 1860 – May 21, 1935) was an American social worker, sociologist, and reformer, known in United States as the "mother of social work." Co-founder of the Hull House in Chicago, she initiated major reforms in child labor, juvenile justice, working conditions, and civil rights. Through her advocacy and example, Addams provided care, respect, and opportunities for the underprivileged, and her efforts established new legal precedents for the protection of society's less fortunate.

A committed pacifist and early feminist, Addams actively supported the campaign for woman suffrage and was an outspoken advocate of internationalism. She participated in the International Congress of Women at the Hague in 1915 and maintained her pacifist stance even after the United States entered World War I in 1917.

Addams' commitment to the needs of others and her international efforts for peace were recognized in 1931 when she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, the first American woman to win the prestigious award.

Life

Born in Cedarville, Illinois, Jane Addams was the eighth child born to her family, the fifth living child at the time of her birth. When she was two, her mother died shortly after a stillbirth. Her father remarried when she was seven, and she acquired two new brothers. Jane, raised initially by an older sister, almost idolized her father.

Her father, a personal friend of Abraham Lincoln and a Quaker, was a state senator and a community leader. Jane learned from him honesty, humility, and a concern for those less fortunate. In her book Twenty Years at Hull-House (Addams 1912) there is a passage discussing the strength of her conscience concerning lying, and that if she had lied, she would not want her father to die without her having confessed her sin to him.

Although only four at the time, she remembers her father weeping at the death of Abraham Lincoln. There were many families in the community who had lost members during the “great war to end slavery,” and they were well respected (one elderly couple had five sons in the war. Four were killed in battle and the youngest was killed in an accident shortly after returning home, leaving the parents childless.). Later, Jane Addams worked to prevent war from breaking out in Europe and spearheaded pacifist movements both in the United States and other countries.

When she was young, Jane had a severe curvature of the back (later corrected by surgery) and viewed herself as being quite ugly. When guests visited the church they attended, she would pretend to be part of her uncle's family as she did not wish others to know that such a great man as her father could have such a horrid child. On one occasion when she had a beautiful new dress, her father suggested she not wear it to church because others would feel badly not to have something so fine.

When she was six, her father took her to visit a mill town. Jane was deeply moved by the squalor of the homes there. At that time she determined that when she grew up, she would live in a nice house but it would not be with other nice houses, rather it would be among houses like these. Later when she and Ellen Gates Starr visited Toynbee Hall in the East End of London, she saw a settlement house in action and decided that she would fulfill her dream from long ago. Returning to America, the two women co-founded Hull House in Chicago, Illinois in 1889. It was one of the first settlement houses in the United States, and it provided welfare for the neighborhood's poor and a center for social reform.

Jane Addams worked tirelessly at Hull House, and with labor unions and other organizations to address problems of poverty and crime, as well as working for women's suffrage and pacifist movements. Her health began to fail her after a heart attack in 1926, although she continued working, serving as president of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom until 1929, and as honorary president for the remainder of her life. Finally, in 1931, she was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace together with Nicholas Murray Butler, but was too ill to accept it in person. She died on May 21, 1935, in Chicago.

Work

Jane Addams was educated in the United States and Europe, graduating from the Rockford Female Seminary (now Rockford College) in Rockford, Illinois. While studying there she was encouraged to be a missionary. Ironically, although she didn't become a missionary in the traditional sense, she established her own mission at Hull House which served society in more ways than most missionaries could expect to do.

She began by starting art, literature, and cooking clubs, and progressed to providing a location for labor unions to meet. She attempted to address injustices as she saw them, dealing with everything from child labor to garbage collection and keeping the streets clean. She fought against women being sold into prostitution and worked to regulate the number of hours women should be allowed to work in factories. However, she did not limit herself to an eight-hour workday: she arose early, and kept such a pace until late in the day that others could not keep up with her. She also encouraged those around her to excel: “If you want to be surrounded by second-rate ability, you will dominate your settlement. If you want the best ability, you must allow great liberty of action among your residents."

At its height, around two thousand people visited Hull House each week. Its facilities included a night school for adults; kindergarten classes; clubs for older children; a public kitchen; an art gallery; a coffeehouse; a gymnasium; a girls club; a swimming pool; a book bindery; a music school; a drama group; a library; and labor-related divisions.

Hull House also served as a women's sociological institution. Addams was a friend and colleague to the early members of the Chicago School of Sociology, influencing their thought through her work in applied sociology as well as, in 1893, co-authoring the Hull-House Maps and Papers that came to define the interests and methodologies of the school. She worked with George Herbert Mead on social reform issues including women's rights and the 1910 Garment Workers' strike. Although academic sociologists of the time defined her work as "social work," Addams did not consider herself a social worker. She combined the central concepts of symbolic interactionism with the theories of cultural feminism and pragmatism to form her sociological ideas. (Deegan 1988)

Jane Addams also worked internationally to support women’s suffrage and to establish world peace. As a leader of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, she emphasized that war was in direct contrast to the nurturing of life. In Patriotism and Pacifists in War Time, she wrote:

This world crisis should be utilized for the creation of an international government to secure without war, those high ends which they now gallantly seek to obtain upon the battlefield. With such a creed can the pacifists of today be accused of selfishness when they urge upon the United States no isolation, nor indifference to moral issues and to the fate of liberty and democracy, but a strenuous endeavor to lead all nations of the earth into an organized international life worthy of civilized men. (Addams 1917)

In addition to her involvement in the American Anti-Imperialist League and the American Sociology Association, she was also a formative member of both the American Civil Liberties Union and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In 1911, she helped establish the National Foundation of Settlements and Neighborhood Centers and became its first president. She was also a leader in women's suffrage and pacifist movements, and took part in the creation of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom in 1915.

Addams was a woman of great integrity, and was highly insulted when she was offered a bribe not to continue to support the unions. She carried out her efforts for world peace despite accusation of being a communist (which she emphatically denied, claiming that she did not even believe in socialism, although her friend Ellen Gates Starr, was a socialist). She held fast to her efforts despite expulsion from the DAR (Daughters of the American Revolution). The Nobel Prize committee twice turned her down because she was too radical. In 1931, she was finally awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, together with American educator Nicholas Murray Butler.

Legacy

Jane Addams was the first American woman to receive the Nobel Prize for Peace, but that hardly touches on the extent of change that came as a result of this one woman's effort. She brought about a change in attitude toward those less fortunate and opened a world to those previously without hope. Hull House brought the first public playground and swimming pool, but also brought art, music and theater to the underprivileged. Even Addams' efforts to make the garbage men accountable (by walking behind their trucks as they went on their rounds) created a change in attitude toward the environment.

Through her work at Hull House and extensive notes about the people of the area, Addams made a major contribution to the field of sociology as well as providing historical documentation about life in Chicago at that time. More profoundly, her legacy lies in the legal changes related to child labor, mandatory education, and the establishment of juvenile courts. She had significant effects on the working conditions for both women and men. Her work with women suffrage, the NAACP and the ACLU also created lasting change. Although she was not able to establish peace during the First World War, her ideas still seem timely.

The work of Jane Addams is inspirational in its magnitude and her words bring awareness of the depth of heart this woman had for humanity. In her essay, Democracy and Social Ethics, she discussed the importance of being concerned about society and even the world, instead of just attending to one's own family:

to pride one’s self on the results of personal effort when the time demands social adjustment, is utterly to fail to apprehend the situation. … a standard of social ethics is not attained by traveling a sequestered byway, but by mixing on the thronged and common road where all must turn out for one another, and at least see the size of one another’s burdens. (Addams 1902)

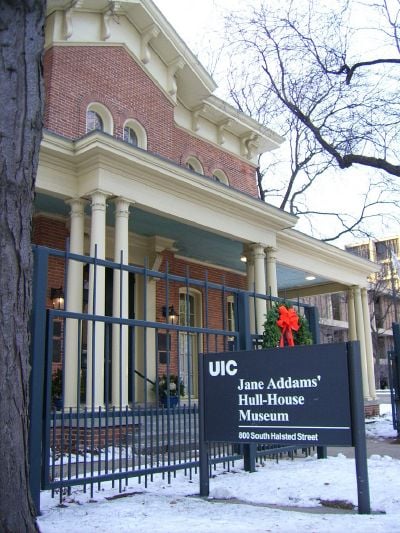

As a force for righteousness and high moral standards, Jane Addams set an example worthy of emulation. A U.S. postage stamp was issued in her honor. Although Hull House itself had to relocate when the University of Illinois established its Chicago campus, the original residence has been preserved as a museum and monument to Jane Addams.

Publications

Addams wrote eleven books and many pamphlets. Among them:

- Addams, Jane. 1902. Democracy and Social Ethics. New York, NY: Macmillan Publishers.

- Addams, Jane. 1905. Children in American Street Trades. New York, NY: National Child Labor Committee.

- Addams, Jane. 1907. New Ideals of Peace. Chautauqua, NY: Chautauqua Press.

- Addams, Jane. 1910. The Wage-Earning Woman and the State. Boston, MA: Boston Equal Suffrage Association for Good Government.

- Addams, Jane. 1911. Symposium: Child Labor on the Stage. New York, NY: National Child Labor Committee.

- Addams, Jane. 1912. Twenty Years at Hull-House, with autobiographical notes. New York, NY: McMillan Publishers. ISBN 1406504920

- Addams, Jane. 1917. Patriotism and Pacifists in War Time.

- Addams, Jane. 1922. Peace and Bread in Time of War. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0252070933

- Addams, Jane. 1923. A New Conscience and an Ancient Evil. New York, NY: Macmillan Publishers.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Deegan, Mary. 1988. Jane Addams and the Men of the Chicago School, 1892-1918. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction, Inc. ISBN 0887388302

External links

All links retrieved March 21, 2018.

- Jane Addams (1860-1935). Harvard University Library Open Collections Program. Women Working, 1870-1930 - a full-text searchable online database with complete access to publications written by Jane Addams.

- Biography The Nobel Peace Prize 1931.

- Jane Addams Hull-House Museum

- Jane Addams Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

| ||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.