Library

A library is a collection of information, sources, resources and services, organized for use, and maintained by a public body, an institution, or a private individual. In the more traditional sense, it means a collection of books. This collection and services are used by people who choose not to — or cannot afford to — purchase an extensive collection themselves, who need material no individual can reasonably be expected to have, or who require professional assistance with their research.

In addition, with the collection of media other than books for storing information, many libraries are now also repositories and access points for maps, prints or other documents and artworks on various storage media such as microfilm, microfiche, audio tapes, CDs, LPs, cassettes, video tapes and DVDs, and provide public facilities to access CD-ROM and subscription databases and the Internet. Thus, modern libraries are increasingly being redefined as places to get unrestricted access to information in many formats and from many sources. In addition to providing materials, they also provide the services of specialists who are experts in matters related to finding and organizing information and interpreting information needs, called librarians. Libraries are valuable institutions for preserving elements of culture and tradition from generation to generation, and expanding them worldwide by enabling a smooth and accurate flow of information.

More recently, libraries are understood as extending beyond the physical walls of a building, by including material accessible by electronic means, and by providing the assistance of librarians in navigating and analyzing tremendous amounts of knowledge with a variety of digital tools.

The term 'library' has itself acquired a secondary meaning: "a collection of useful material for common use," and in this sense is used in fields such as computer science, mathematics and statistics, electronics and biology.

History

Early archives

The first libraries were only partly libraries, being composed for the most part of unpublished records, which are usually viewed as archives. Archaeological findings from the ancient city-states of Sumer have revealed temple rooms full of clay tablets in cuneiform script. These archives were made up almost completely of the records of commercial transactions or inventories, with only a few documents touching theological matters, historical records or legends. Things were much the same in the government and temple records on papyrus of Ancient Egypt.

The earliest discovered private archives were kept at Ugarit; besides correspondence and inventories, texts of myths may have been standardized practice-texts for teaching new scribes. Tablets were written in the previously unknown Ugaritic script, with 30 cuneiform signs comprising the earliest alphabetic script, from about 2000 B.C.E.

Private or personal libraries made up of non-fiction and fiction books (as opposed to the state or institutional records kept in archives) first appeared in classical Greece. The first ones appeared some time near the fifth century B.C.E. The celebrated book collectors of Hellenistic Antiquity were listed in the late second century in Deipnosophistae:

Polycrates of Samos and Pisistratus who was tyrant of Athens, and Euclides (Not the familiar Euclid) who was himself also an Athenian and Nicorrates of Samos and even the kings of Pergamos, and Euripides the poet and Aristotle the philosopher, and Nelius his librarian; from whom they say our countryman[1] Ptolemæus, surnamed Philadelphus, bought them all, and transported them, with all those which he had collected at Athens and at Rhodes to his own beautiful Alexandria.[2]

All these libraries were Greek; the cultivated Hellenized diners in Deipnosophistae pass over the libraries of Rome in silence. At the Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum, apparently the villa of Caesar's father-in-law, the Greek library has been partly preserved in volcanic ash; archaeologists speculate that a Latin library, kept separate from the Greek one, may await discovery at the site. Libraries were filled with parchment scrolls as at Pergamum and on papyrus scrolls as at Alexandria: export of prepared writing materials was a staple of commerce. There were a few institutional or royal libraries like the Library of Alexandria which were open to an educated public, but on the whole collections were private. In those rare cases where it was possible for a scholar to consult library books there seems to have been no direct access to the stacks. In all recorded cases the books were kept in a relatively small room where the staff went to get them for the readers, who had to consult them in an adjoining hall or covered walkway.

Chinese libraries

Little is known about early Chinese libraries, save what is written about the imperial library which began with the Qin Dynasty (221 - 206 B.C.E.) The early documents are geneology records and the history of the dynasty. One of the curators of the imperial library in the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.E. - 220 C.E.) [3]is believed to have been the first to establish a library classification system and the first book notation system. At this time the library catalog was written on scrolls of fine silk and stored in silk bags.

In Persia many libraries were established by the Zoroastrian elite and the Persian Kings. Among the first ones was a royal library in Isfahan. One of the most important public libraries established around 667 C.E. in south-western Iran was the Library of Gundishapur. It was a part of a bigger scientific complex located at the Academy of Gundishapur.

Western libraries

In the West, the first public libraries were established under the Roman Empire as each succeeding emperor strove to open one or many which outshone that of his predecessor. Unlike the Greek libraries, readers had direct access to the scrolls, which were kept on shelves built into the walls of a large room. Reading or copying was normally done in the room itself. The surviving records give only a few instances of lending features. As a rule Roman public libraries were bilingual: they had a Latin room and a Greek room. Most of the large Roman baths were also cultural centers, built from the start with a library, with the usual two room arrangement for Greek and Latin texts.

In the sixth century, at the very close of the Classical period, the great libraries of the Mediterranean world remained those of Constantinople and Alexandria. Cassiodorus, minister to Theodoric, established a monastery at Vivarium in the heel of Italy with a library where he attempted to bring Greek learning to Latin readers and preserve texts both sacred and secular for future generations. As its unofficial librarian, Cassiodorus not only collected as many manuscripts as he could, he also wrote treatises aimed at instructing his monks in the proper uses of reading and methods for copying texts accurately. In the end, however, the library at Vivarium was dispersed and lost within a century.

Christian and Muslim

Elsewhere in the Early Middle Ages, after the fall of the Western Roman Empire and before the rise of the large Western Christian monastery libraries beginning at Montecassino, libraries were found in scattered places in the Christian Middle East. Upon the rise of Islam, libraries in newly Islamic lands knew a brief period of expansion in the Middle East, North Africa, Sicily and Spain. Like the Christian libraries, they mostly contained books which were made of paper, and took a codex or modern form instead of scrolls; they could be found in mosques, private homes, and universities. Some mosques sponsored public libraries. Ibn al-Nadim's bibliography Fihrist (Index) demonstrates the devotion of medieval Muslim scholars to books and reliable sources; it contains a description of thousands of books circulating in the Islamic world circa 1000, including an entire section for books about the doctrines of other religions. Unfortunately, modern Islamic libraries for the most part do not hold these antique books; many were lost, destroyed by Mongols, or removed to European libraries and museums during the colonial period.[4]

By the eighth century first Persians and then Arabs had imported the craft of paper making from China, with a mill already at work in Baghdad in 794. By the ninth century completely public libraries started to appear in many Islamic cities. They were called "halls of Science" or dar al-'ilm. They were each endowed by Islamic sects with the purpose of representing their tenets as well as promoting the dissemination of secular knowledge. The libraries often employed translators and copyists in large numbers, in order to render into Arabic the bulk of the available Persian, Greek and Roman non-fiction and the classics of literature. This flowering of Islamic learning ceased after a few centuries as the Islamic world began to turn against experimentation and learning. After a few centuries many of these libraries were destroyed by Mongolian invasion. Others were victim of wars and religious strife in the Islamic world. However, a few examples of these medieval libraries, such as the libraries of Chinguetti in northern Mauritania, West Africa, remain intact and relatively unchanged even today. Another ancient library from this period which is still operational and expanding is the Central Library of Astan Quds Razavi in the Iranian city of Mashhad, which has been operating for more than six centuries.

The contents of these Islamic libraries were copied by Christian monks in Muslim/Christian border areas, particularly Spain and Sicily. From there they eventually made their way into other parts of Christian Europe. These copies joined works that had been preserved directly by Christian monks from Greek and Roman originals, as well as copies Western Christian monks made of Byzantine works. The resulting conglomerate libraries are the basis of every modern library today.

Medieval library design reflected the fact that these manuscripts—created via the labor-intensive process of hand copying—were valuable possessions. Library architecture developed in response to the need for security. Librarians often chained books to lecterns, armaria(wooden chests), or shelves, in well-lit rooms. Despite this protectiveness, many libraries were willing to lend their books if provided with security deposits (usually money or a book of equal value). Monastic libraries lent and borrowed books from each other frequently and lending policy was often theologically grounded. For example, the Franciscan monasteries loaned books to each other without a security deposit since according to their vow of poverty only the entire order could own property. In 1212 the council of Paris condemned those monasteries that still forbade loaning books, reminding them that lending is "one of the chief works of mercy." [5]

The earliest example in England of a library to be endowed for the benefit of users who were not members of an institution such as a cathedral or college was the Francis Trigge Chained Library in Grantham, Lincolnshire, established in 1598. The library still exists and can justifiably claim to be the forerunner of later public library systems.

The early libraries located in monastic cloisters and associated with scriptoria were collections of lecterns with books chained to them. Shelves built above and between back-to-back lecterns were the beginning of bookpresses. The chain was attached at the fore-edge of a book rather than to its spine. Book presses came to be arranged in carrels (perpendicular to the walls and therefore to the windows) in order to maximize lighting, with low bookcases in front of the windows. This stall system (fixed bookcases perpendicular to exterior walls pierced by closely spaced windows) was characteristic of English institutional libraries. In Continental libraries, bookcases were arranged parallel to and against the walls. This wall system was first introduced on a large scale in Spain's El Escorial.

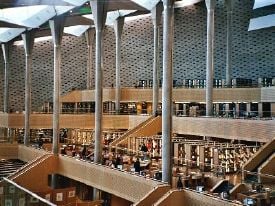

As books became more common, the need for chaining them lessened. But as the number of books in libraries increased, so did the need for compact storage and access with adequate lighting, giving birth to the stack system, which involved keeping a library's collection of books in a space separate from the reading room, an arrangement which arose in the nineteenth century. Book stacks quickly evolved into a fairly standard form in which the cast iron and steel frameworks supporting the bookshelves also supported the floors, which often were built of translucent blocks to permit the passage of light (but were not transparent, for reasons of modesty). With the introduction of electrical lighting, it had a huge impact on how the library operated. Also, the use of glass floors was largely discontinued, though floors were still often composed of metal grating to allow air to circulate in multi-story stacks. Ultimately, even more space was needed, and a method of moving shelves on tracks (compact shelving) was introduced to cut down on otherwise wasted aisle space.

Types of libraries

Libraries can be divided into categories by several methods:

- by the entity (institution, municipality, or corporate body) that supports or perpetuates them

- school libraries

- private libraries

- corporate libraries

- government libraries

- academic libraries

- historical society libraries

- by the type of documents or materials they hold

- digital libraries

- data libraries

- picture (photograph) libraries

- photographic transparencies (slide) libraries

- tool libraries

- by the subject matter of documents they hold

- architecture libraries

- fine arts libraries

- law libraries

- medical libraries

- military libraries

- theological libraries

- by the users they serve

- military communities

- by traditional professional divisions:

- Academic libraries — These libraries are located on the campuses of colleges and universities and serve primarily the students and faculty of that and other academic institutions. Some academic libraries, especially those at public institutions, are accessible to of the general public in whole or in part.

- School libraries — Most public and private primary and secondary schools have libraries designed to support the school's curriculum.

- Research libraries — These libraries are intended for supporting scholarly research, and therefore maintain permanent collections and attempt to provide access to all necessary material. Research libraries are most often academic libraries or national libraries, but many large special libraries have research libraries within their special field and a very few of the largest public libraries also serve as research libraries.

- Public libraries or public lending libraries — These libraries provide service to the general public and make at least some of their books available for borrowing, so that readers may use them at home over a period of days or weeks. Typically, libraries issue library cards to community members wishing to borrow books. Many public libraries also serve as community organizations that provide free services and events to the public, such as babysitting classes and story time.

- Special libraries — All other libraries fall into this category. Many private businesses and public organizations, including hospitals, museums, research laboratories, law firms, and many government departments and agencies, maintain their own libraries for the use of their employees in doing specialized research related to their work. Special libraries may or may not be accessible to some identified part of the general public. Branches of a large academic or research libraries dealing with particular subjects are also usually called "special libraries": they are generally associated with one or more academic departments. Special libraries are distinguished from special collections, which are branches or parts of a library intended for rare books, manuscripts, and similar material.

- The final method of dividing library types is also the simplest. Many institutions make a distinction between circulating libraries (where materials are expected and intended to be loaned to patrons, institutions, or other libraries) and collecting libraries (where the materials are selected on a basis of their natures or subject matter). Many modern libraries are a mixture of both, as they contain a general collection for circulation, and a reference collection which is often more specialized, as well as restricted to the library premises.

Also, the governments of most major countries support national libraries. Three noteworthy examples are the U.S. Library of Congress, Canada's Library and Archives Canada, and the British Library.

Description

Libraries have materials arranged in a specified order according to a library classification system, so that items may be located quickly and collections may be browsed efficiently. Some libraries have additional galleries beyond the public ones, where reference materials are stored. These reference stacks may be open to selected members of the public. Others require patrons to submit a "stack request," which is a request for an assistant to retrieve the material from the closed stacks.

Larger libraries are often broken down into departments staffed by both paraprofessionals and professional librarians.

- Circulation handles user accounts and the loaning/returning and shelving of materials.

- Technical Services works behind the scenes cataloging and processing new materials and deaccessioning weeded materials.

- Reference staffs a reference desk answering user questions (using structured reference interviews), instructing users, and developing library programming. Reference may be further broken down by user groups or materials; common collections are children's literature, young adult literature, and genealogy materials.

- Collection Development orders materials and maintains materials budgets.

Library use

Library instruction, which advocates education for library users, has been practiced in the U.S. since the nineteenth century. One of the early leaders was John Cotton Dana. The basic form of library instruction is generally known as information literacy.

Libraries inform the public of what materials are available in their collections and how to access that information. Before the computer age, this was accomplished by the card catalog — a cabinet containing many drawers filled with index cards that identified books and other materials. In a large library, the card catalog often filled a large room. The emergence of the Internet, however, has led to the adoption of electronic catalog databases (often referred to as "webcats" or as OPACs, for "online public access catalog"), which allow users to search the library's holdings from any location with Internet access. This style of catalog maintenance is compatible with new types of libraries, such as digital libraries and distributed libraries, as well as older libraries that have been retrofitted. Electronic catalog databases are disfavored by some who believe that the old card catalog system was both easier to navigate and allowed retention of information, by writing directly on the cards, that is lost in the electronic systems. Nevertheless, most modern libraries now utilize electronic catalog databases.

Library management

Basic tasks in library management include the planning of acquisitions (which materials the library should acquire, by purchase or otherwise), library classification of acquired materials, preservation of materials (especially rare and fragile archival materials such as manuscripts), the deaccessioning of materials, patron borrowing of materials, and developing and administering library computer systems. More long-term issues include the planning of the construction of new libraries or extensions to existing ones, and the development and implementation of outreach services and reading-enhancement services (such as adult literacy and children's programming).

Funding problems

In the United States, among other countries, libraries in financially limited communities compete with other public institutions such as police, firefighters, schools, and health care.

Many communities are closing down or reducing the capability of their library systems, at the same time balancing their budgets. Survey data suggests the public values free public libraries. A Public Agenda survey in 2006 reported 84 percent of the public said maintaining free library services should be a top priority for their local library. But the survey also found the public was mostly unaware of financial difficulties facing their libraries. The survey did not ask those surveyed whether they valued free library services more than other specific services, such as firefighting.[6]

In various cost-benefit studies libraries continue to provide an exceptional return on the dollar.[7]

Famous libraries

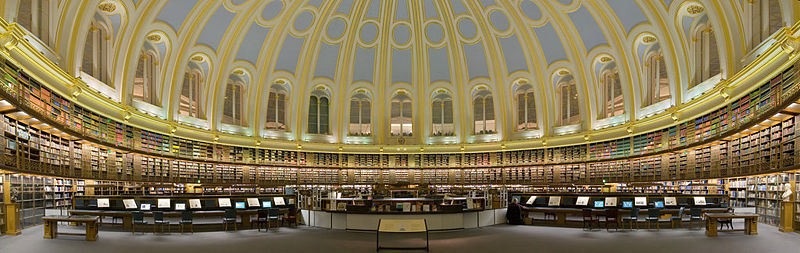

Some of the greatest libraries in the world are research libraries. The most famous ones include The Humanities and Social Sciences Library of the New York Public Library in New York City, the Russian National Library in Saint Petersburg, the British Library in London, Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, and the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C..

- Assurbanipal's library at Nineveh was created between years 669 B.C.E. - 631 B.C.E.

- Egypt's ancient third century B.C.E. Library of Alexandria, and modern Bibliotheca Alexandrina

- Ambrosian Library in Milan opened to the public, December 8, 1609.

- Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF) in Paris, 1720.

- Boston Public Library in Boston, 1826.

- Bodleian Library at University of Oxford 1602, books collection begin around 1252.

- British Library in London created in 1973 by the British Library Act of 1972.

- British Library of Political and Economic Science in London, 1896.

- Butler Library at Columbia University, 1934

- Cambridge University Library at University of Cambridge, 1931.

- Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh in Pittsburgh, 1895.

- Carolina Rediviva at Uppsala University, 1841

- Dutch Royal Library in The Hague, 1798

- The European Library, 2004

- Firestone Library at Princeton University, 1948

- Fisher Library at the University of Sydney (largest in the Southern Hemisphere), 1908

- Franklin Public Library in Franklin, Massachusetts (the first public library in the U.S.; original books donated by Benjamin Franklin in 1731)

- Free Library of Philadelphia in Philadelphia established February 18, 1891.

- Garrison Library in Gibraltar, 1793.

- Harold B. Lee Library at Brigham Young University, 1924.

- House of Commons Library, Westminster, London. Established 1818.

- Jenkins Law Library in Philadelphia founded 1802.

- Jewish National and University Library in Jerusalem, Israel, 1892.

- John Rylands Library in Manchester 1972.

- Leiden University Library at Leiden University in Leiden began at 1575 with cofiscated monastery books. Officially open in October 31, 1587.

- Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. 1800, began with donation of Thomas Jefferson's personal library.

- Library of Sir Thomas Browne, 1711

- Mitchell Library in Glasgow (Europe's largest public reference library)

- National Library of Australia in Canberra, Australia

- National Library of Ireland, Dublin

- New York Public Library in New York

- Osler Library of the History of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Canada

- Sassanid's ancient Library of Gondishapur around 489.

- National Library of Iran, 1937.

- Powell Library at UCLA, part of the UCLA Library.

- Russian State Library in Moscow, 1862.

- Royal Library in Copenhagen, 1793.

- Seattle Central Library

- Staatsbibliothek in Berlin

- State Library of Victoria in Melbourne

- Sterling Memorial Library at Yale University, 1931.

- Vatican Library in Vatican City, 1448 (but existed before).

- Widener Library at Harvard University (Harvard University Library including all branches has probably the largest academic collection overall.)

- The St. Phillips Church Parsonage Provincial Library, established in 1698 in Charleston, South Carolina, was the first public lending library in the American Colonies. See also Benjamin Franklin's free public library in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

- Boston Public Library, an early public lending library in America, was established in 1848.

- Haskell Free Library and Opera House, "The only library in America with no books."

- St. Marys Church, Reigate, Surrey houses the first public lending library in England. Opened March 14, 1701.

- Kitchener Public Library, in the erstwhile "library capital of Canada."

Some libraries devoted to a single subject:

- Chess libraries

- Esperanto libraries

- Family History Library in Salt Lake City, Utah, the world's largest genealogy library.

See also

- Printmaking

- Digital library

- Carnegie library

- Chinese Library Classification (CLC)

- Dewey Decimal Classification

- Digital reference services

- Interlibrary loan

- International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions

- Librarian

- Library and information science

- Library catalog

- Library of Congress Classification

- Public Library of Science

Notes

- ↑ The writer was Alexandrian; the sophisticates in Deipnosophistae were at a banquet in Rome.

- ↑ See Library of Alexandria.

- ↑ Ssu-Ma Ch'ien, edited by William H. Nienhauser, The Grand Scribe's Records Volume 1. The Basic Annals of Pre-Han China (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995, ISBN 0253340217).

- ↑ John L. Esposito (ed.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Modern Islamic World (Oxford University Press, 1995, ISBN 0195066138).

- ↑ George Haven Putnam, Books and Their Makers in the Middle Ages (Hillary, 1962).

- ↑ Public Agenda, Long Overdue: A Fresh Look at Public Attitudes About Libraries in the 21st Century (Public Agenda, 2006, ISBN 978-1889483870).

- ↑ Glen Holt, Measuring Outcomes:Applying Cost-Benefit Analysis to Middle-Sized and Smaller Public Libraries Library Trends 51(3)(Winter 2003): 424-440. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ch'ien, Ssu-Ma, William H. Nienhauser (ed.). The Grand Scribe's Records Volume 1. The Basic Annals of Pre-Han China. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995. ISBN 0253340217

- Esposito, John L. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Modern Islamic World. Oxford University Press, 1995. ISBN 0195066138

- Nienhauser, William H..Jr. The Grand Scribe's Records Volume 1. The Basic Annals of Pre-Han China. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995. ISBN 0253340217

- Public Agenda. Long Overdue: A Fresh Look at Public Attitudes About Libraries in the 21st Century. Public Agenda, 2006. ISBN 978-1889483870

- Putnam, George Haven. Books and Their Makers in the Middle Ages. Hillary House Publishers, 1962. ASIN B00CD77OAC

External links

All links retrieved October 25, 2022.

- Libraries of the World and their Catalogues compiled by a retired librarian.

- Libraries : Frequently Asked Questions.

- International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions.

- A Library Primer, by John Cotton Dana, 1903, setting out the basics of organizing and running a library.

- Libraries, Catholic Encyclopedia.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.