Ugarit

Ugarit (modern Ras Shamra near Latakia, Syria) was an ancient cosmopolitan port city, sited on the Mediterranean coast, reaching the height of its civilization from about 1450 B.C.E. until 1200 B.C.E.

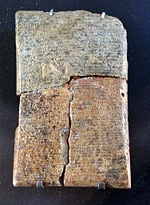

Rediscovered in 1928, the site dates back to 6000 B.C.E., making it one of the earliest known urban centers. It has yielded a treasure trove of archaeological information, including several late Bronze Age libraries of clay tablets in various ancient languages. The most significant of these finds was the religious text known as the Baal Cycle, which details the mythology of several Canaanite gods and provides previously unknown insights into how the religious culture of Canaan influenced the writers of the Bible.

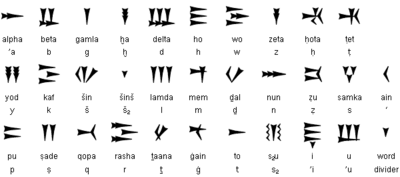

Ugarit had a rich artistic tradition, influenced by both Egyptian and Mycenaean cultures. The discoveries there also revealed Ugarit's previously known cuneiform alphabetic script, an important precursor to the true alphabet.

Ugarit's golden age came to an end around 1200 B.C.E., possibly as the result of the invasion of the Sea Peoples as well as earthquakes and famines which are known to have plagued the area. People continued to inhabit the area in smaller settlements until at least the fourth century B.C.E.

The archaeological site of Ras Shamra, a name given by local residents meaning “fennel hill,” is still active and continues to yield important results.

Archaeological site

Ugarit's location was forgotten until 1928, when an Alawite peasant accidentally opened an old tomb while plowing a field. The discovered area was the Necropolis of Ugarit, located in the nearby seaport of Minet el-Beida. Excavations have since revealed an important city that took its place alongside the ancient cities of Ur and Eridu as a cradle of urban culture. Its prehistory reaches back to ca. 6000 B.C.E., perhaps because it was both a port and entrance to the trade route to the inland centers which lay on the Euphrates and Tigris rivers.

Most early excavations of Ugarit were undertaken by archaeologist Claude Schaeffer from the Prehistoric and Gallo-Roman Museum in Strasbourg. The digs uncovered a major royal palace of 90 rooms, laid out around eight enclosed courtyards, many ambitious private dwellings, and libraries. Crowning the hill where the city was built were two main temples: one to Baal the "king of the gods," and one to Dagon, the god of fertility and wheat. The most important piece of literature recovered from Ugarit is arguably the Baal Cycle text, describing the basis for the religion and cult of the Canaanite Baal and the dramatic myth of his ascendancy to the head of the pantheon of Canaanite deities.

The site yielded several deposits of cuneiform clay tablets, discovered at a palace library, a temple library, and—apparently unique in the world at the time—two private libraries, all dating from the last phase of Ugarit, around 1200 B.C.E. One of the private libraries belonged to a diplomat named Rapanu and contained legal, economic, diplomatic, administrative, literary, and religious texts.

Sometimes known as the Ras Shamra Tablets, the texts found at Ugarit were written in four languages: Sumerian, Hurrian, Akkadian, and Ugaritic (of which nothing had been known before). No less than seven different scripts were in use at Ugarit: Egyptian and Luwian hieroglyphics, and Cypro-Minoan, Sumerian, Akkadian, Hurrian, and Ugaritic cuneiform. During excavations in 1958, yet another library of tablets was uncovered. These were, however, sold on the black market and not immediately recovered.

The Ras Shamra Tablets are now housed at the Institute for Antiquity and Christianity at the Claremont School of Theology in Claremont, California. They were edited by Loren R. Fisher in 1971. In 1973, an additional archive containing around 120 tablets was discovered. In 1994, more than 300 further tablets were discovered in a large stone building on the site, covering the final years of the Bronze Age city's existence.

History

Though the site is thought to have been inhabited earlier, Neolithic Ugarit was already important enough to be fortified with a wall early on, perhaps by 6000 B.C.E., making it one of the world's earliest known walled cities. The first written evidence mentioning the city by name comes from the nearby city of Ebla, ca. 1800 B.C.E. By this time Ugarit had passed into the sphere of influence of Egypt, which deeply influenced its art and culture. The earliest Ugaritic contact with Egypt—and the first exact dating of Ugaritic civilization—comes from a carnelian bead found at the site which had been identified with the Middle Kingdom pharaoh Senusret I, 1971–1926 B.C.E. A stela and a statuette from the Egyptian pharaohs Senusret III and Amenemhet III have also been found. However, it is unclear at what time these monuments arrived at Ugarit.

Letters discovered at Amarna dating from ca. 1350 B.C.E. include royal correspondence from Ugarit: one letter from King Ammittamru I and his queen, and another from King Niqmaddu II. During its high culture, from the sixteenth to the thirteenth centuries B.C.E., Ugarit remained in constant touch with Egypt and Cyprus (then called Alashiya).

Destruction

The last Bronze Age king of Ugarit, Ammurapi, was a contemporary of the Hittite king Suppiluliuma II. A letter by the king is preserved, in which Ammurapi stresses the seriousness of the crisis faced by many Near Eastern states from invasion by the advancing Sea Peoples. Ammurapi highlights the desperate situation Ugarit faced in letter RS 18.147, written in response to a plea for assistance from the king of Alasiya (Cyprus):

My father, behold, the enemy's ships came (here); my cities were burned, and they did evil things in my country. Does not my father know that all my troops and chariots are in the Land of Hatti, and all my ships are in the Land of Lukka? … Thus, the country is abandoned to itself. May my father know it: the seven ships of the enemy that came here inflicted much damage upon us.

Evidence suggests that Ugarit was burned to the ground at the end of the Bronze Age. An Egyptian sword bearing the name of pharaoh Merneptah was found in the destruction levels. However, a cuneiform tablet found in 1986 shows that Ugarit was destroyed after the death of Merneptah. It is now generally agreed that Ugarit had already been destroyed by the eighth year of Ramesses III in 1178 B.C.E.

The destruction was followed by a hiatus in settlement at Ugarit. Many other Mediterranean cultures were deeply disordered at the same time, by invasions of the mysterious "Sea Peoples," and also by famines and earthquakes.

Alphabet and language

Scribes in Ugarit appear to have originated the cuneiform-based Ugaritic alphabet around 1400 B.C.E. It consisted of 30 letters, corresponding to sounds, adapted from cuneiform characters and inscribed on clay tablets. A debate exists as to whether the Phoenician or Ugaritic alphabet was invented first. Evidence suggests that the two systems were not wholly independent inventions. Later, it would be the Phoenician alphabet that spread through the Aegean and on Phoenician trade routes throughout the Mediterranean. The Phoenician system thus became the basis for the first true alphabet, when it was adopted by Greek speakers who modified some of its signs to represent vowel sounds as well. This system was in turn adopted and modified by populations in Italy, including ancestors of the Romans).

Compared with the difficulty of writing the widely used diplomatic language of Akkadian in cuneiform—as exemplified in the Amarna Letters—the flexibility of an alphabet opened a horizon of literacy to many more kinds of people. In contrast, the syllabary used in Mycenaean Greek palace sites at about the same time (called Linear B) was so cumbersome that literacy was limited largely to administrative specialists.

The Ugaritic language is attested in texts from the fourteenth through the twelfth century B.C.E. Ugaritic is a Northwest Semitic language, related to Hebrew and Aramaic. However, its grammatical features are similar to those found in classical Arabic and Akkadian.

Religion and mythology

Literature from tablets found in the libraries of Ugarit includes mythological texts written in a narrative poetry. Fragments of several poetic works have been identified: the "Legend of Kirtu," the "Legend of Danel," the religious texts that describe Baal-Hadad's conflicts with Yam and Mot, and other fragments.

Ugaritic religion centered on the chief god, Ilu or El, whose titles included "Father of mankind" and "Creator of the creation." The Court of El was referred to as the (plural) 'lhm or Elohim, a word later used by the biblical writers to describe the Hebrew deity and translated into English as "God," in the singular.

Beside El, the most important of the other gods were the Lord and king of the god Baal-Hadad; the mother goddess Athirat or Asherah; the sea god Yam; Baal's sister Anat; and the desert god of death, Mot. Other deities worshiped at Ugarit included Dagon (grain), Resheph (healing), Kothar-and-Khasis (the divine craftsman), Shahar (dawn or the sun), Shalim (dusk), and Tirosh (grapes).

El, which was also the name of the God of Abraham, was described as an aged deity with white hair, seated on a throne. Although El was the highest deity and the father of many of the other gods, he had bequeathed the kingship of the gods to Baal when Baal had defeated the previous incumbent, Yam, who had turned tyrant and attempted to claim El's wife Asherah as his consort. At Ugarit, Baal was known by several titles: “king of the gods,” “the Most High (Elyon),” “Beelzebub|Prince Baal," and “the Rider on the Clouds.”

The discovery of the Ugaritic archives has been of great significance to biblical scholarship, as these archives for the first time provided a detailed description of Canaanite religious beliefs during the period directly preceding the Israelite settlement. These texts show significant parallels to biblical literature. Ugaritic poetry has many elements later found in Hebrew poetry in its use of parallelism, meter, and rhythms. In some cases biblical texts seems to have borrowed directly from Ugaritic tradition. For example, when Proverbs 9 personifies wisdom and folly as a two women, it repeats a theme found in the earlier Ugaritic tradition, with some lines of the two texts being almost identical. The Legend of Danel, meanwhile, is thought by some scholars to have influenced the Hebrew tradition of the wise and just Daniel of later Jewish legend. Titles and descriptions of Ugaritic deities also bear a marked similarity to the imagery and epithets used by the biblical writers.

Kings of Ugarit

| Ruler | Reigned | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Niqmaddu I | ||

| Yaqurum I | ||

| Ibiranu I | ||

| Ammittamru I | ca. 1350 B.C.E. | |

| Niqmaddu II | 1349 - 1315 B.C.E. | Contemporary of Suppiluliuma I of the Hittites |

| Arhalba | 1315 - 1313 B.C.E. | |

| Niqmepa | 1312 - 1260 B.C.E. | Treaty with Mursili II of the Hittites, Son of Niqmadu II, |

| Ammittamru II | 1260 - 1235 B.C.E. | Contemporary of Bentisina of Amurru, Son of Niqmepa |

| Ibiranu | 1235 - 1220 B.C.E. | |

| Niqmaddu III | 1220 - 1215 B.C.E. | |

| Ammurapi | ca. 1200 B.C.E. | Contemporary of Chancellor Bay of Egypt, Ugarit is destroyed |

See also

- Amarna letters

- Ebla

- Baal cycle

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Craigie, Peter C. Ugarit and the Old Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1983. ISBN 9780802819284

- Drews, Robert. 1995. The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe ca. 1200 B.C.E. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691025916

- Driver, Godfrey Rolles, and John C. L. Gibson. Canaanite Myths and Legends. Edinburgh: Clark, 1978. ISBN 9780567023513

- Smith, Mark S. Untold Stories: The Bible and Ugaritic Studies in the Twentieth Century. Peabody: Hendrickson, 2001. ISBN 1565635752

- Yon, Marguerite. The City of Ugarit at Tell Ras Shamra. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2006. ISBN 1575060299

External links

All links retrieved May 2, 2023.

- Ugarit and the Bible Quartz Hill School of Theology, theology.edu

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.