Cyprus

| Κυπριακή Δημοκρατία Kıbrıs Cumhuriyeti Republic of Cyprus |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem: Ýmnos is tin Eleftherían Ὕμνος εἰς τὴν Ἐλευθερίαν Hymn to Liberty1 |

||||||

| |

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) | Nicosia (Λευκωσία, Lefkoşa) 35°08′N 33°28′E | |||||

| Official languages | Greek Turkish[1] |

|||||

| Ethnic groups (2001) | 77% Greek 18%Turkish 5% others[2] |

|||||

| Demonym | Cypriot | |||||

| Government | Presidential republic | |||||

| - | President | Dimitris Christofias | ||||

| Independence | ||||||

| - | Zürich and London Agreement | 19 February 1959 | ||||

| - | from the United Kingdom | 16 August 1960 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 9,251 km² (167th) 3,572 (Includes North) sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | Negligible | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2010 estimate | 803,147 [3] (Does not include North) 1,088,503 (whole island) |

||||

| - | Density | 117/km² (115th) 221/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2010 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $23.190 billion[4] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $28,256[4] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2010 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $23.174 billion[4] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $28,237[4] | ||||

| Gini (2005) | 29 (low) (19th) | |||||

| Currency | Euro2 (EUR) |

|||||

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .cy3 | |||||

| Calling code | [[+357]] | |||||

| 1 | Also the national anthem of Greece. | |||||

| 2 | Before 2008, the Cypriot pound. | |||||

| 3 | The .eu domain is also used, shared with other European Union member states. | |||||

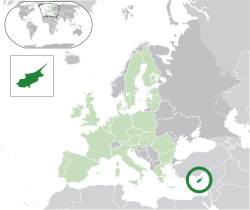

Cyprus (Greek: Κύπρος, Kýpros; Turkish: Kıbrıs), officially the Republic of Cyprus (Greek: Κυπριακή Δημοκρατία, Kypriakí Dhimokratía; Turkish: Kıbrıs Cumhuriyeti) is an Eurasian island nation in the eastern part of the Mediterranean Sea south of the Anatolian peninsula (Asia Minor) or modern-day Turkey. It is the third largest island in the Mediterranean Sea.

The island has a rich history with human habitation dating back at least 10,000 years and played a role in the ancient history of both southern Europe and the Middle East. Today it remains a symbol of the division between the two civilizations which often vied for control over its strategic location and natural resources.

After World War II, Cyprus gained independence from British colonial rule and a democratic constitution was enacted. However, underlying tensions between Greek and Turkish residents soon escalated. Following 11 years of alternating violence and peaceful attempts at reconciliation, including the establishment of the United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus in 1964, Turkey launched a two-stage invasion of the island in 1974 in response to an Athens-engineered coup which had overthrown the legitimate Cypriot government.

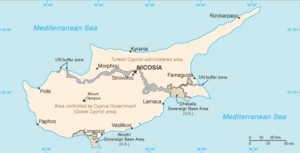

The invasion led to the internal displacement of thousands of Greek and Turkish Cypriots and the subsequent establishment of a disputed territorial regime to govern the invaded area, calling itself the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, separated from the south by the UN-controlled Green Line and recognized only by Turkey. Today the Republic of Cyprus is a developed country and a member of the European Union since May 1, 2004.

Etymology

The name Cyprus has a somewhat uncertain etymology. A likely explanation is that it comes from the Greek word for the Mediterranean cypress tree, κυπάρισσος (kypárissos). Another suggestion is that the name derives from the Greek name of the henna plant, κύπρος (kýpros). Another school of thought suggests that it stems from the Eteocypriot word for copper, and is related to the Sumerian word for copper, (zubar), or even the word for bronze (kubar), due to the large deposits of copper ore found on the island.

Geography

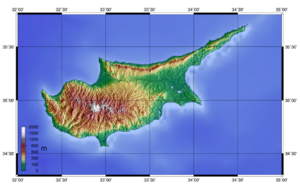

The third largest island in the Mediterranean Sea (after Sicily and Sardinia), Cyprus is geographically situated in the eastern Mediterranean and just south of the Anatolian peninsula (or Asia Minor). Thus, it is commonly included in the Middle East. Turkey is 75 kilometers (47 miles) north; other neighboring countries include Syria and Lebanon to the east, Israel to the southeast, Egypt to the south, and Greece to the west-north-west.

Historically, Cyprus has been at the crossroads between Europe, Western Asia, and Northern Africa, with lengthy periods of mainly Greek and intermittent Anatolian, Levantine, and British influences. Thus, it is generally considered a transcontinental island.

The climate is temperate and Mediterranean with dry summers and variably rainy winters. Summer temperatures range from warm at higher elevations in the Troodos mountains to hot in the lowlands. Winter temperatures are mild at lower elevations, where snow rarely occurs, but are significantly colder in the mountains, where there is sufficient snow for a seasonal ski facility.

History

Prehistoric and ancient Cyprus

The earliest confirmed site of human activity on the island is Aeotokremnos situated on the Akrotiri Peninsula on the south coast. Evidence from this site indicates that hunter-gatherers were active on the island from around 10,000 B.C.E.. There is also evidence that suggests that there may be short lived occupation sites contemporary with Aeotokremnos on the west coast of the island in the area of the Akamas.

The appearance of more settled village pastorialists is evident at around 8200 B.C.E.. These people probably practiced a limited form of agriculture and animal husbandry, supplemented by hunting. Important remains from this early-Neolithic period can be found at Mylouthkia, Shillourokambos, Tenta and later towards the end of this period the famous village of Khirokitia.

Following this, during the Painted-Pottery Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods, small scale settlements and activity areas were in use all over the island. A rich craft industry produced decorated pottery and figurines of stone quite distinct from the cultures of the surrounding mainland.

During the Bronze Age, the people of Cyprus learned to work the rich copper mines of the island. The Mycenæan culture seems to have reached Cyprus at around 1600 B.C.E., and several Greek and Phœnician settlements that belong to the Iron Age can also be found on the island. Cyprus became a significant trading partner with Egypt about 1500 B.C.E..

Around 1200 B.C.E., the Sea Peoples, groups of seafarers who invaded eastern Anatolia, Syria, Palestine, Cyprus, and Egypt, may have arrived in Cyprus, although the nature of their influence is disputed. The Phœnicians arrived at the island in the early first millennium B.C.E.. In those times, Cyprus supplied the Greeks with timber for their fleets.

In the sixth century B.C.E., Amasis of Egypt conquered Cyprus, which soon fell under the rule of the Persians when Cambyses conquered Egypt. In the Persian Empire, Cyprus formed part of the fifth satrapy (area ruled by ancient Persian governor), and in addition to other tributes had to supply the Persians with ships and crews. In this work, the Greeks of Cyprus had as companions the Greeks of Ionia (west coast of Anatolia) with whom they forged closer ties. When the Ionian Greeks revolted against Persia in 499 B.C.E., the Cypriots (except for the city of Amathus) joined in, led by Onesilos, who dethroned his brother, the king of Salamis, for refusing to fight for independence. The Persians reacted quickly, sending a considerable force against Onesilos. The Persians finally won, despite Ionian support for the Cypriots.

After their defeat, the Greeks mounted various expeditions in order to liberate Cyprus from Persian rule, but these efforts gained only temporary victories. Eventually, under Alexander the Great (356-323 B.C.E.) the island went over to the Macedonians. Later, the Ptolemies of Egypt controlled it; finally Rome annexed it in 58-57 B.C.E.

Cyprus was visited by the Apostles Paul, Barnabas, and Mark the Evangelist who came to the island at the outset of their first missionary journey in 45 C.E. After their arrival at Salamis they proceeded to Paphos, where they converted the Roman Governor Sergius Paulus to Christianity. This biblical report (Acts 13) is cited by some Cypriots as evidence that theirs was the first country in the world governed by a Christian ruler.

Post-classical Cyprus

Cyprus became part of the Byzantine Empire after the partitioning of the Roman Empire in 395, and remained so for almost 800 years, interrupted by a brief period of Arab domination and influence.

After the rule of the rebellious Byzantine Emperor Isaac Komnenos, King Richard I of England captured the island in 1191 during the Third Crusade. On May 6, 1191, Richard's fleet arrived in the port of Lemesos and took the city. When Isaac arrived to stop the Crusaders he discovered he was too late and retired to Kolossi Castle. Richard called Isaac to negotiations, and Isaac demanded Richard's departure. Richard then led his cavalry into battle against Isaac's army in Tremetusia. The few Roman Catholics of the island joined Richard's army, and so did the island's nobles, who were dissatisfied with Isaac's seven years of rule. Though Isaac and his men fought bravely, Richard's army was larger and better equipped, assuring his victory. Isaac continued to resist from the castle of Pentadactylos but after the siege of his fortress of Kantara, he finally surrendered. In a fit of sardonic irony, Richard had Isaac confined with silver chains, scrupulously abiding by a previous promise that he would not place Isaac in irons should he be taken prisoner.

Richard became the new ruler of Cyprus, gaining for the Crusade a major supply base that was not under immediate threat from the Turks, as was Tyre. Richard looted the island and massacred those who tried to resist him. He and most of his army left Cyprus for the Holy Land early in June of 1191. In his absence, Cyprus was governed by Richard Camville.

In 1192, Guy of Lusignan purchased the island, in compensation for the loss of his kingdom from the Templars. The Republic of Venice took control in 1489 after the death of the last Lusignan queen.

Throughout the period of Venetian rule, Ottoman Cyprus was vulnerable to Turkish raids.

Modern Cyprus

Ottoman rule

In 1489, the first year of Venetian control, Turks attacked the Karpasia Peninsula, pillaging and taking captives to be sold into slavery. In 1539 the Turkish fleet attacked and destroyed Limassol. Fearing the ever-expanding Ottoman Empire, the Venetians had fortified Famagusta, Nicosia, and Kyrenia, but most other cities were easy prey. In the summer of 1570, the Turks launched a full-scale invasion, seizing Nicosia. After a long siege, Famagusta fell the following year.

Three centuries of Ottoman rule followed, in which the Latin church was suppressed and the Orthodox hierarchy was restored. The Orthodox archbishop was made responsible for tax collection, and feudal tenure was abolished, giving the Greeks the right to acquire land by purchase, and thus become owners. Taxes were greatly reduced, but later grew increasingly onerous.

Thousands of Turks were already settled on the island and during the seventeenth century the Turkish population grew rapidly. However, dissatisfaction grew with the Ottoman administration, which was widely viewed by both Turk and Greeks as inefficient, arbitrary, and corrupt. There were Turkish uprisings in 1764 and 1833. In 1821 the Orthodox archbishop was hanged on suspicion of links and sympathies with Greek rebels on the mainland. Between 1572 and 1668, numerous uprisings took place on the island, in which both Greeks and Turk peasants took part. All ended in failure.

By 1872, the population of the island had risen to 144,000, comprised of 44,000 Muslims (mostly Turks) and 100,000 Christians (mostly Greeks).

British rule

Cyprus was placed under British control on June 4, 1878 as a result of the Cyprus Convention, which granted control of the island to Britain in return for British support of the Ottoman Empire in the Russian-Turkish War.

Famagusta harbor was completed in June 1906. By this time the island was a strategic naval outpost for the British Empire, shoring up influence over the Eastern Mediterranean and the Suez Canal, the crucial main route to India. Cyprus was formally annexed by the United Kingdom in 1913 in the run-up to the First World War, since their former British ally, Turkey, had joined the Central Powers. Many Cypriots, now British subjects, signed up to fight in the British Army, promised by the British that when the war finished, Cyprus would be united with Greece.

After World War I, Cyprus remained under British rule. A different outcome would occur, however, after World War II. In the 1950s, Greek Cypriots began to demand union with Greece. In 1950, a huge majority of Cypriots voted in a referendum in support of such a union. In 1955, the struggle against British rule erupted, lasting until 1959.

Independence was attained in 1960 after negotiations between the United Kingdom, Greece, and Turkey. The UK ceded the island under a constitution allocating government posts and public offices by ethnic quota, but retained two small base areas under British sovereignty.

Post-independence

Cyprus was declared an independent state on August 16, 1960. The constitution of the new state divided the people of Cyprus into a majority and minority, based on national origin. Shortly after, the two communities became entangled in a constitutional crisis. In November 1963, Archbishop Makarios, the first President of the Republic of Cyprus, proposed 13 Amendments to the constitution designed, from the Greek point of view, to remove some of the causes of friction. The Turkish population of Cyprus, however, rejected the proposal, arguing that the amendments would have restricted the rights of the Turkish Cypriot community.

Unable to reach a solution, the government of the Republic of Cyprus brought the matter before the United Nations. UN Security Council Resolution 186/1964, the first of a series of UN resolutions on the Cyprus issue, provided for the stationing of the UN peacekeeping force (UNFICYP) on the island, and the start of UN efforts at mediation.

By 1974, dissatisfaction among Greek nationalist elements in favor of the long-term goal of unification with Greece precipitated a coup d'etat against President Makarios, sponsored by the military government of Greece and led by officers in the Cypriot National Guard. The new regime replaced Makarios with Nikos Giorgiades Sampson as president, and Bishop Gennadios as head of the Cypriot Orthodox Church.

Seven days after these events, Turkey invaded Cyprus by sea and air, on July 20, 1974. Turkey claimed this action was conducted to uphold its obligation under a 1960 treaty commitment, "to reinstate the constitution of the Republic of Cyprus." After it became clear that neither the Greeks nor the Turks on Cyprus supported the coup, the new regime was resolved. However, some areas remained under the Turkish occupation army. Talks in Geneva involving Greece, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the two Cypriot factions failed in mid-August. By the end of September, Turkish forces controlled 37 percent of the island's territory.

The events of the summer of 1974 have dominated Cypriot politics ever since and have been a major point of contention between Greek and Turkish Cypriots, as well as between Greece and Turkey.

Independent Turkish state

Turkish Cypriots proclaimed a separate state, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) under Rauf Denktaş on November 15, 1983. The UN Security Council, in its Resolution 541 of November 18, 1983, declared the action legally invalid and called for a withdrawal of Turkish troops. Turkey is the only country to date that recognizes the administration on the northern third of Cyprus. Turkey does not recognize the Republic of Cyprus's authority over the whole island and refers to it as the Greek Cypriot administration.

Renewed UN peace-proposal efforts in 1984 and 1985 were unsuccessful, and in May 1985 a constitution for the TRNC was approved by referendum.

Government and Politics

After its independence, the Republic of Cyprus became a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement despite all three guarantor powers (Greece, Turkey, and the UK) being North Atlantic Treaty Organization members. Cyprus left the Non-Aligned Movement in 2004 to join the European Union, although it retains special observer status.

The 1960 Cypriot Constitution provided for a presidential system of government with independent executive, legislative, and judicial branches, as well as a complex system of checks and balances, including a weighted power-sharing ratio designed to protect the interests of the Turkish Cypriots. The executive branch, for example, was headed by a Greek Cypriot president, and a Turkish Cypriot vice-president, elected by their respective communities for five-year terms and each possessing a right of veto over certain types of legislation and executive decisions. The House of Representatives was elected on the basis of separate voters' rolls. However, since 1964, following clashes between the Greek and Turkish communities, the Turkish Cypriot seats in the House remained vacant and the Greek Cypriot Communal Chamber was abolished.

In the north, Turkish Cypriots established separate institutions with a popularly elected de facto President and a Prime Minister responsible to a National Assembly, exercising joint executive powers. Since 1983, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) has existed as a separate state. In 1985, the TRNC adopted a formal constitution and held its first elections.

Political division

Continued difficulties in finding a settlement presented a potential obstacle to Cypriot entry to the European Union, for which the government had applied in 1997. UN-sponsored talks between the Greek and Turkish leaders, continued intensively in 2002, but without resolution. In December 2002, the EU formally invited Cyprus to join in 2004, insisting that EU membership would apply to the whole island and hoping that it would provide a significant enticement for reunification resulting from the outcome of ongoing talks. However, after the election of Tassos Papadopoulos as the new president of Cyprus, negotiations stalled, and the UN declared that the talks had failed.

A United Nations plan sponsored by Secretary-General Kofi Annan was announced in March, 2004. Cypriot civilians on both sides voted on the plan in separate referendums on April 24. The Greek side overwhelmingly rejected the Annan Plan, while the Turkish side voted in favor.

In May 2004, Cyprus entered the EU, although in practice membership only applies to the southern part of the island which is in the control of the Republic of Cyprus.

In July, 2006, the Greek Cypriot leader, Tassos Papadopoulos, and Turkish Cypriot leader, Mehmet Ali Talat, signed a set of principles and decisions recognizing that the status quo was unacceptable and that a comprehensive settlement was both desirable and possible. They agreed to begin a two-track process involving discussions by technical committees regarding issues affecting the day-to-day life of the people and, concurrently, consideration by working groups on substantive issues, leading to a comprehensive settlement. They also committed to ending mutual recriminations.

Exclaves and enclaves

Cyprus has four exclaves—territories geographically separated from the main part. These are all located in territory that belongs to the British Sovereign Base Area of Dhekelia. The first two are the villages of Ormidhia and Xylotymvou. Additionally there is the Dhekelia Power Station, which is divided by a British road into two parts. The northern part is an enclave (territory geographically separated from the main part by surrounding alien territory), like the two villages, whereas the southern part is located by the sea and therefore not an enclave—although it has no territorial waters of its own.

The UN buffer zone, separating the territory controlled by the Turkish Cypriot administration from the rest of Cyprus, runs up against Dhekelia and picks up again from its east side, off Ayios Nikolaos (connected to the rest of Dhekelia by a thin land corridor). In that sense, the buffer zone turns the south-east corner of the island, the Paralimni area, into a de facto, though not de jure, exclave.

Economy

Economic affairs in Cyprus are dominated by the division of the country. Nevertheless, the economy of the island has grown greatly. The north maintains a lower standard of living than the south due to international embargoes, and is still reliant on Turkey for aid. However, increased revenues through tourism and a recent construction boom have led to rapid economic development in recent years.

Recently, oil has been discovered in the sea south of Cyprus between Cyprus and Egypt and talks are under way with Egypt to reach an agreement as to the exploitation of these resources.

The Cypriot economy is prosperous and has diversified in recent years. Cyprus has been sought as a basis for several offshore businesses, due to its highly developed infrastructure. The economic policy of the Cyprus government has focused on meeting the criteria for admission to the European Union. Eventual adoption of the euro currency is required of all new countries joining the European Union, and the Cyprus government is scheduled to adopt the currency on January 1, 2008. The largest bank on the island is the Bank of Cyprus.

The economy of the north is dominated by the services sector including the public sector, trade, tourism, and education, with smaller agriculture and light manufacturing sectors. The Turkish Cypriot economy has benefited from the conditional opening of the border with the south.

Demographics

Greek and Turkish Cypriots share many customs but maintain separate ethnic identities based on religion, language, and close ties with their respective motherlands. Greeks comprise 77 percent of the island's population, Turks 18 percent, while the remaining 5 percent are of other ethnicities. The population is estimated at 855,000.

After the Turkish invasion of 1974, about 150,000 Turks from Anatolia settled in the north. Northern Cyprus now claims 265,100 inhabitants. In the years since the census data was gathered in 2000, Cyprus has also seen a large influx of guest workers from countries such as Thailand, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka, as well as major increases in the numbers of permanent British residents. The island is also home to a significant Armenian minority, as well as a large refugee population consisting of people mainly from Serbia, Palestine, and Lebanon. Since the country joined the European Union, a significant Polish population has also grown up, joining sizable communities from Russia and Ukraine (mostly Pontic Greeks), immigrating after the fall of the Soviet Union.

Most Greek Cypriots, and thus the majority of the population of Cyprus, belong to the Autocephalous Orthodox Church of Cyprus (Cypriot Orthodox Church), whereas most Turkish Cypriots are Sunni Muslims. Church attendance is relatively high, and Cyprus is known as one of the most religious countries in the European Union. In addition, there are also small Roman Catholic, Maronite, and Armenian Apostolic communities in Cyprus.

Greek is the predominant language in the south, while Turkish is spoken in the north and by some Greek Cypriots, too. This delineation is only reflective of the post-1974 division of the island, which involved an expulsion of Greek Cypriots from the north and the analogous move of Turkish Cypriots from the south. Historically, the Greek language was largely spoken by all Greek Cypriots and by many Turkish Cypriots too, given the fact that the Greek Cypriots formed the majority of the population. Cypriot Turkish is a rather distinctive dialect of Turkish, and uses a number of sound alternations not found in standard Turkish.

English is widely understood and is taught in schools from the primary age. Many official documents are published in English as well as the official languages of Greek and Turkish.

Human rights

Both Turkish Cypriots living in the Republic of Cyprus and Greek Cypriots in Turkish areas report discrimination directed towards them. However, the focus on the division of the island has sometimes masked other human rights issues.

Prostitution is rife in both the Republic of Cyprus and the TRNC, and the island has been criticized as forming one of the main routes of human trafficking of girls from Eastern Europe for the sex trade. [5] The regime in the north has been the focus of occasional freedom of speech criticisms regarding the heavy-handed treatment of newspaper editors. Reports on mistreatment of domestic servants, often immigrant workers from Third World countries, are frequent in the Greek Cypriot press.

Amnesty International has criticized the Cypriot government over the treatment of foreign nationals, particularly asylum seekers, in Cypriot police stations and prisons. The 2005 report also restated Amnesty International's long standing concern over discrimination towards the Roma peoples in Cyprus.[6]

Education

Cyprus has a well-developed system of primary and secondary education offering both public and private education. State schools are generally seen as equivalent in their quality of education to private sector institutions. Graduates of public schools are required to take an entrance examination in order to enroll at the University of Cyprus or other universities in Greece. Private school students usually study in Britain and the United States, although some of them go to the University of Cyprus or Greek universities.

According to the 1960 constitution, education was under the control of the two communities (the communal chambers). After 1974, the Cypriot system followed the Greek system and the Turkish system exists in the area not under the Republic's effective control. In the north there are several universities, which are mostly attended by Turkish Cypriot and Turkish students, the most notable of which is Eastern Mediterranean University. The qualifications issued by the universities are not formally recognized by the Republic, the EU, or American institutions: however, most universities outside Cyprus accept that the degrees they offer are broadly equivalent to Turkish university standards, enabling students to go on to postgraduate study outside the TRNC.

Notes

- ↑ Constitution of the Republic of Cyprus: "The official languages of the Republic are Greek and Turkish" (Appendix D, Part 01, Article 3)

- ↑ Error on call to template:cite web: Parameters url and title must be specified. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- ↑ Total population as of 1 January. Eurostat. Retrieved January 3, 2012.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Error on call to template:cite web: Parameters url and title must be specified. International Monetary Fund.

- ↑ Jacqueline Theodoulou, A shame on our society, www.cyprus-mail.com. Retrieved September 22, 2007.

- ↑ Amnesty International 2005 Report on Cyprus web.amnesty.org. Retireved September 22, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Anastasiou, Harry. The Broken Olive Branch: Nationalism Ethnic Conflict and the Quest for Peace in Cyprus. Author House, 2006. ISBN 1425943608

- Brewin, Christopher. European Union and Cyprus. Eothen Press, 2000. ISBN 0906719240

- Dodd, Clement (ed.). Cyprus: The Need for New Perspectives. The Eothen Press, 1999. ISBN 0906719232

- Gibbons, Harry Scott. The Genocide Files. Charles Bravos Publishers, 1997. ISBN 0951446428

- Hannay, David. Cyprus: The Search for a Solution. I.B. Tauris, 2005. ISBN 1850436657

- Hitchens, Christopher. Hostage to History: Cyprus from the Ottomans to Kissinger. Verso; 3rd edition, 1997. ISBN 1859841899

- Ker-Lindsay, James. EU Accession and UN Peacemaking in Cyprus. Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. ISBN 1403996903

- Mirbagheri, Fari. Cyprus and International Peacemaking. Routledge; 1st edition, 1998. ISBN 978-0415919753

- Oberling, Pierre. The Road to Bellapais. East European Monographs, 1982. ISBN 0880330007

- O'Malley, Brendan and Ian Craig. The Cyprus Conspiracy. I. B. Tauris; New Ed edition, 2001. ISBN 1860647375

- Palley, Claire. An International Relations Debacle: The UN Secretary-General's Mission of Good Offices in Cyprus, 1999-2004. Hart Publishing, 2005. ISBN 184113578X

- Papadakis, Yiannis. Echoes from the Dead Zone: Across the Cyprus Divide. I.B. Tauris, 2005. ISBN 185043428X

- Plumer, Aytug. Cyprus, 1963-64: The Fateful Years. Cyrep (Lefkosa), 2003. ISBN 9756912189

- Richmond, Oliver. Mediating in Cyprus. Routledge; 1 edition, 1998. ISBN 0714644315

- Richmond, Oliver and James Ker-Lindsay (eds.). The Work of the UN in Cyprus: Promoting Peace and Development. Palgrave Macmillan, 2001. ISBN 0333912713

- Tocci, Nathalie. EU Accession Dynamics and Conflict Resolution: Catalyzing Peace or Consolidating Partition in Cyprus?. Ashgate Publishing, 2004. ISBN 0754643107

External links

All links retrieved January 12, 2024.

- Constitution of the Republic of Cyprus www.kypros.org.

- Cyprus US State Department - Cyprus. www.state.gov.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.