Serbia

| –†–Ķ–Ņ—É–Ī–Ľ–ł–ļ–į –°—Ä–Ī–ł—ė–į Republika Srbija Republic of Serbia |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem:¬†–Ď–ĺ–∂–Ķ –Ņ—Ä–į–≤–ī–Ķ / God of justice |

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) | Belgrade 44¬į48‚Ä≤N 20¬į28‚Ä≤E | |||||

| Official languages | Serbian1 | |||||

| Ethnic groups (2002) | 82.9% Serbs, 3.9% Hungarians, 1.8% Bosniaks, 1.4% Roma, 10.0% others[1] (excluding Kosovo) |

|||||

| Demonym | Serbian | |||||

| Government | Parliamentary republic | |||||

| ¬†-¬† | President | Boris Tadińá | ||||

| ¬†-¬† | Prime Minister | Mirko Cvetkovińá | ||||

| Formation | ||||||

|  -  | First state | 768  | ||||

|  -  | Kingdom | 1217  | ||||

|  -  | Empire | 1346  | ||||

|  -  | Recognized as suzerain principality | 1817  | ||||

|  -  | De-jure independence | 1878  | ||||

|  -  | Independent republic | 2006  | ||||

| Area | ||||||

|  -  | Total | 88 361 km² (112th) 34 116 sq mi  |

||||

|  -  | Water (%) | 0.13 (including Kosovo) |

||||

| Population | ||||||

|  -  |  estimate | 7,387,367[2] (excluding Kosovo)  |

||||

|  -  | Density | 107,46/km² (94th) 297/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2011 estimate | |||||

|  -  | Total | $79.013 billion[3] (75th) | ||||

|  -  | Per capita | $10,661 (excluding Kosovo) (74th) | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2011 estimate | |||||

|  -  | Total | 46.444 billion[3] (80th) | ||||

|  -  | Per capita | $6,267[3] (excluding Kosovo) (79th) | ||||

| Gini (2008) | 26 (low)  | |||||

| Currency | Serbian dinar (RSD) |

|||||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |||||

|  -  | Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .rs, .—Ā—Ä–Ī | |||||

| Calling code | [[+381]] | |||||

| 1 See also regional minority languages recognized by the ECRML | ||||||

Serbia, officially the Republic of Serbia is a landlocked country in central and south-eastern Europe, covering the southern part of the Pannonian Plain and the central part of the Balkan Peninsula. It is bordered by Hungary on the north, Romania and Bulgaria on the east, Albania and Republic of Macedonia on the south, and Montenegro, Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina on the west.

The Republic of Serbia comprises Serbia proper and two autonomous provinces‚ÄĒKosovo and Metohija in the south that was under the administration of the United Nations Mission in Kosovo in 2007, and Vojvodina in the north.

Serbia, in particular the valley of the Morava, which is the easiest way of traveling overland from continental Europe to Greece and Asia Minor, is often described as "the crossroads between East and West," and is one of the reasons for its turbulent history.

The capital Belgrade has been captured 60 times (by the Romans, Huns, Turks, and Germans, among others), and destroyed 38 times. In World War I, Serbia had 1,264,000 casualties‚ÄĒ28 percent of its total population, and 58 percent of its male population. In World War II, Yugoslavia had 1,700,000 (10.8 percent of the population) people killed, and damages were estimated at $9.1-billion.

Geography

Serbia is bordered by Hungary on the north, Romania and Bulgaria on the east, Albania and Republic of Macedonia on the south, and Montenegro, Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina on the west. These borders were established after the end of World War II, when Serbia became a federal unit within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

Serbia covers a total area of 34,116 square miles (88,361km²), which places it at 113th largest place in the world, or slightly larger than South Carolina in the United States.

Serbia's terrain ranges from rich, fertile plains of the northern Vojvodina region, limestone ranges and basins in the east, and ancient mountains and hills in the southeast. The Danube River dominates the north. A tributary, the Morava River, flows through the more mountainous southern regions.

Four mountain systems meet in Serbia. The Dinaric Alps in the west cover the greatest territory, and stretch from northwest to southeast. The Carpathian Mountains and the Balkan Mountains stretch in north-south direction in the eastern Serbia, west of the Morava valley. Ancient mountains along the South Morava belong to Rilo-Rhodope Mountain system. The Sar Mountains of Kosovo form the border with Albania, with one of the highest peaks in the region, Djeravica, at 8714 feet (2656 meters).

Serbia has a continental climate in the north, with cold winters, and hot, humid summers, and well distributed rainfall patterns, and a more Adriatic climate in the south, with hot, dry summers and autumns, and relatively cold winters with heavy inland snowfall. The continental climate of Vojvodina has July temperatures of about 71¬įF (22¬įC), and January temperatures of around 30¬įF (-1 ¬įC). Precipitation ranges from 22 inches to 75 inches (560mm to 1900mm) a year, depending on elevation and exposure.

The Danube river flows through the northern third of the country, forming the border with Croatia and part of Romania. The Sava river forms the southern border of the Vojvodina province, flows into the Danube in central Belgrade, and bypasses the hills of the FruŇ°ka Gora in the west. Sixty kilometers to the northeast of Belgrade, the Tisza river flows into the Danube and ends its 1350¬†km long journey from Ukraine, and the partially navigable TimiŇü River (60¬†km/350¬†km) flows into the Danube near Pancevo. The Begej river flows into Tisa near Titel. All five rivers are navigable, connecting the country with Northern and Western Europe' (through the Rhine-Main-Danube Canal‚ÄďNorth Sea route), to Eastern Europe (via the Tisa‚Äď, TimiŇü River‚Äď, Begej‚Äď and Danube‚ÄďBlack sea routes) and to Southern Europe (via the Sava river).

Serbia has no lakes other than Lake Palic in the Vojvodina, with a surface area of less than two square miles (five square kilometers). Other water bodies are reservoirs behind hydroelectric dams.

The dry Vojvodina plains were a grassland steppe, before Austrian agriculture started in the area in the eighteenth century, although forests at one time dominated the area. Up to one-third of Serbia proper is in broad-leaved forest, mostly oak and beech. Serbia has a rich diversity of wild animals, including deer, and bears. Wild pigs are a distinctive feature of beech forests in the mountains. Serbia has five national parks: FruŇ°ka Gora, Kopaonik, Tara, ńźerdap (Iron Gate), and ҆ar mountain.

Natural resources include oil, gas, coal, iron ore, copper, lead, zinc, antimony, chromite, nickel, gold, silver, magnesium, pyrite, limestone, marble, salt, arable land. Natural hazards include destructive earthquakes.

Environmental issues include air pollution around Belgrade and other industrial cities, and water pollution from industrial wastes dumped into the Sava.

The capital is Belgrade, a cosmopolitan city at the confluence of the Danube and Sava rivers. First settled around 4800 B.C.E., Belgrade had a population in 2002 of 1,576,124. Other cities in Serbia proper with populations surpassing the 100,000 mark include Novi Sad, NiŇ°, Kragujevac, Leskovac, Subotica, Zrenjanin, KruŇ°evac, Panńćevo, Kraljevo, ńĆańćak, and Smederevo. Cities in Kosovo with populations surpassing the 100,000 mark include PriŇ°tina, Prizren, Djakovica, Peńá and Kosovska Mitrovica.

History

Pre-human occupation in the Serbia region dates back 35,000 years, although dense Neolithic settlement dates from about 7000 B.C.E. to 3500 B.C.E. in the Pannonian Basin, along the Sava and Danube rivers, and spreading north into Hungary along the Tisa River, and south down the Morava-Vardar corridor.

Illyrians

Semi-nomadic pastoral people from the Russian steppes infiltrated the region from 3500 B.C.E. They rode horses, had horse-drawn vehicles, built hill forts such as Vucedol, near Vukovar, traded amber, gold, and bronze, and had a superior military technology. These people included the Illyrians, who settled through the western Balkans. By the seventh century B.C.E., the Illyrians could work with iron, which they traded with the emerging Greek city-states. In the mid-fourth century B.C.E., Philip II of Macedon and his son Alexander the Great extended their empire into the region. From 300 B.C.E., iron-skilled Celts began to settle the area. Belgrade is partly of Celtic origin.

Roman conquest

Romans seeking iron, copper, precious metals, slaves, and crops began to move into the Balkan Peninsula in the late third century B.C.E., and struggled for domination against fierce resistance for 300 years. The Illyrians were finally subdued in 9 C.E., and their land became the province of Illyricum, while eastern Serbia was conquered in 29 B.C.E. and made part of the province of Moesia. Roads, arenas, aqueducts, bridges, fortifications, and towns were built. Invasions by Goths, Huns, Bulgars, Avars, and others gradually weakened Roman influence.

The basic name, Serboi, describing a people living north of the Caucasus, appeared in the works of Tacitus, Plinius and Ptolemy in the first and second century C.E. Emperor Diocletian in 285 C.E. began dividing the empire along a line that ran north from the modern Albanian-Montenegrin border. This division enabled Greek culture to penetrate the Balkans, especially after the defeat of an Avar-Persian army in 626 by the Byzantines. Christianity had been introduced during the Roman period, but the region had reverted to paganism by the time the Slavs had arrived.

Serbs arrive

Byzantine Emperor Heraclius (575‚Äď641) commissioned Slavic tribal groups to drive Avars and Bulgars toward the east. Slavs settled the Balkans, and tribes known as the Serbs settled inland of the Dalmatian coast in an area extending from eastern Herzegovina, across northern Montenegro, and into southeastern Serbia. Vlastimir created the Serb state around 850, centered on an area in southern Serbia known as RaŇ°ka. That kingdom accepted the supremacy of Constantinople, the start of an on-going link between the Serbian people and Orthodox Christianity. Byzantine emperor Michael III (840-867) sent brothers Cyril and Methodius to evangelize the Slavs. They invented a script based on the Slavic tongue, which was initially known as ‚ÄúGlagolitic,‚ÄĚ but later revised using Greek-type characters and became known as ‚ÄúCyrillic.‚ÄĚ

Serbian golden age

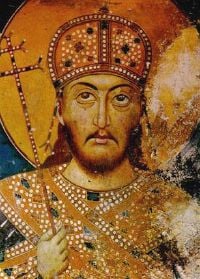

A stable Slavic state appeared when Stefan Nemanja assumed the throne of RaŇ°ka in 1168. In 1196, he abdicated, handing the crown to his son Stefan, who in 1217 was named by Pope Honorius III the ‚ÄúKing of Serbia, Dalmatia, and Bosnia.‚ÄĚ The Nemanjic dynasty ruled for 200 years, helped by the collapse of the Byzantine Empire under the impact of the Fourth Crusade (1204). During the reign of Emperor Dusan (1331-1355), the state incorporated Thessaly, Epirus, Macedonia, all of modern Albania and Montenegro, a substantial part of eastern Bosnia, and modern Serbia as far north as the Danube, and was referred to as the Golden Age. Dusan promulgated the famous Zakonik (code of laws) in 1349, which fused the law of Constantinople with Serb folk custom. The economy, law, military, and religion prospered during the rule of the House of Nemanjic. But by nature a soldier and a conqueror, DuŇ°an did not make any systematic effort to stabilize or administer his gains.

Turkish conquest

The Serbian Empire disintegrated into rival clans, and were defeated by the Turks in 1371 at the Battle of Chernomen, and in 1389 at the historic Battle of Kosovo. That defeat was hallowed in heroic ballads. Stories, such as of Maid of Kosovo, who helped the wounded and dying on the battlefield, have become symbols of Serbian nationhood. The northern Serbian territories were conquered in 1459 following the siege of the "temporary" capital Smederevo. Bosnia fell a few years after Smederevo, and Herzegovina in 1482. Belgrade was the last major Balkan city to endure Ottoman onslaughts, as it joined Catholic Kingdom of Hungary, following a Turkish defeat in 1456. It held out for another 70 years, succumbing to the Ottomans in 1521, alongside the greater part of the Kingdom of Hungary. Another short-lasting incarnation of the Serbian state was under Emperor Jovan Nenad in sixteenth-century Vojvodina, which also was conquered by the Ottoman Empire, before passing to the Habsburg Empire, where it remained for about two centuries.

Ottoman rule

Most of Serbia was under Ottoman occupation between 1459 and 1804, despite three Austrian invasions and numerous rebellions (such as the Banat Uprising). The Ottoman period was a defining one in the history of the country‚ÄĒSlavic, Byzantine, Arabic and Turkish cultures combined. The Ottoman feudal system centered on the sultan and his court in Constantinople, and revolved around extracting revenue. Under the timar system, the sultan leased areas (timarli) to a leaseholder (a spahi) who had the right to extract taxes. The spahi was expected to support and arm himself to serve the sultan. The Ottomans ruled through local knezes, or Christian ‚Äúheadmen,‚ÄĚ who might act as a tax negotiator, a justice of the peace, as a labor organizer, or as a spokesman for the Christian population,

Generally, there was no attempt to spread Islam by the sword. All Muslims were regarded as the ummah. Any person could join the ruling group by converting to Islam. Each non-Muslim religious community was called a millet, five of which were recognized: Orthodox, Gregorian Armenian, Roman Catholic, Jewish, and Protestant. Christians were exempted from military service, and the tax burden was lighter than previously, although heavier than for the Muslim population. Serbs were forbidden to own property, and to learn to read and write. Some Christian boys between the ages of 10 and 20 were conscripted, taken to Constantinople, converted to Islam, and employed in a variety of roles ‚Äď some as administrators, and others as Janissaries, an elite, celibate order of infantrymen. Most Serbs kept their culture and religion through the long period of Ottoman rule.

Austrian-Turkish wars

European powers, and Austria in particular, fought many wars against the Ottoman Empire, relying on the help of the Serbs. During the Austrian‚ÄďTurkish War (1593‚Äď1606), in 1594, the Serbs staged an uprising in Banat‚ÄĒthe Pannonian plain part of Turkey, and sultan Murad III retaliated by burning the relics of Saint Sava‚ÄĒthe most sacred thing for all Serbs, honored even by Muslims of Serbian origin. Serbs created another center of resistance in Herzegovina but when peace was signed by Turkey and Austria they were abandoned to Turkish vengeance. This sequence of events became usual in the centuries that followed.

During the Great War (1683‚Äď1690) between Turkey and the Holy League‚ÄĒcreated with the sponsorship of the Pope and including Austria, Poland and Venice‚ÄĒthese three powers incited the Serbs to rebel, and soon uprisings and guerrilla warfare spread throughout the western Balkans. When the Austrians retreated, numerous Serbs abandoned their homesteads and headed north, led by patriarch Arsenije ńĆarnojevińá.

A further Austria-Ottoman war, launched by Prince Eugene of Savoy, took place in 1716‚Äď1718, and resulted in the Ottomans losing all possessions in the Danube basin, as well as northern Serbia and northern Bosnia, parts of Dalmatia and the Peloponnesus. The last Austrian-Ottoman war was the Dubica War (1788‚Äď1791), when the Austrians urged the Christians in Bosnia to rebel. No wars were fought afterwards until the twentieth century that marked the fall of both mighty empires.

Principality of Serbia

The First Serbian Uprising of 1804‚Äď1813, led by ńźorńĎe Petrovińá (also known as KarańĎorńĎe or "Black George"), and the Second Serbian Uprising of 1815, resulted in the Principality of Serbia. As it was semi-independent from the Ottoman Empire, it is considered to be the precursor of modern Serbia. In 1876, Montenegro, Serbia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina declared war against the Ottoman Empire and proclaimed their unification. Serbia and Montenegro secured sovereignty, which was formally recognized at the Congress of Berlin in 1878, leaving Bosnia and the Sanjak of Novi Pazar to Austria-Hungary, which blocked their unification until the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913 and World War I.

From 1815 to 1903, the Serbian state was ruled by the House of Obrenovińá, except from 1842 to 1858, when Serbia was ruled by Prince Aleksandar KarańĎorńĎevińá. In 1903, the House of Obrenovińá was replaced by the House of KarańĎorńĎevińá, who were descendants of ńźorńĎe Petrovińá.

In 1848, Serbs in the northern part of present-day Serbia, which was ruled by the Austrian Empire, established an autonomous region known as the Serbian Vojvodina. As of 1849, the region was transformed into a new Austrian crownland known as the Vojvodina of Serbia and TamiŇ° Banat. The crownland was abolished in 1860, demands for Vojvodina region autonomy re-emerged in 1918.

World War I

On June 28, 1914, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria at Sarajevo in Austria-Hungary by Gavrilo Princip, a South Slav unionist, Austrian citizen and member of Young Bosnia, led to Austria-Hungary declaring war on Serbia, culminating in World War I. The Serbian Army won several major victories against Austria-Hungary at the beginning of World War I, but it was overpowered by the joint forces of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria in 1915. Most of its army and some people went to exile to Greece and Corfu where it healed, regrouped and returned to the Macedonian front to lead a final breakthrough through enemy lines on September 15, 1918, freeing Serbia again and ending the World War I on November 11. In World War I, Serbia had 1,264,000 casualties‚ÄĒ28 percent of its total population, and 58 percent of its male population.

The Kingdom of Yugoslavia

The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes was formed in 1918. A Serb representative opened fire on the opposition benches in the Parliament, killing two outright and mortally wounding the leader of the Croatian Peasants Party, Stjepan Radińá in 1928. Taking advantage of the resulting crisis, King Alexander I of Yugoslavia banned national political parties in 1929, assumed executive power, and renamed the country Yugoslavia. However, neither the Fascists in Italy, the Nazis in Germany, nor Stalin in the Soviet Union favored the policies pursued by Alexander I. During an official visit to France in 1934, the king was assassinated in Marseille by a member of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization‚ÄĒan extreme nationalist organization in Bulgaria‚ÄĒwith the cooperation of the UstaŇ°e‚ÄĒa Croatian Fascist separatist organization. Croatian leader Vlatko Mańćek and his party managed to extort the creation of the Croatian banovina (administrative province) in 1939.

World War II

The reigning Serbian monarch signed a treaty with Hitler (as did Bulgaria, Romania, and Hungary). However a popular uprising rejected this agreement, and the king fled. In April 1941, the Luftwaffe bombed Belgrade and other cities, and troops from Germany, Italy, Hungary, and Bulgaria invaded Yugoslavia. After a brief war, Yugoslavia surrendered. The western parts of the country together with Bosnia and Herzegovina were turned into a Nazi puppet state called the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) and ruled by the Ustashe. Serbia was set up as another puppet state under Serbian army general Milan Nedińá. Hungary annexed the northern territories, Bulgaria annexed eastern and southern territories, while Albania, which was under the sponsorship of fascist Italy, annexed Kosovo and Metohia. Montenegro lost territories to Albania and was then occupied by Italian troops. Slovenia was divided between Germany and Italy, which also seized the islands in the Adriatic.

In Serbia, the German authorities organized several concentration camps for Jews and members of the Partisan resistance movement. The biggest camps were Banjica and SajmiŇ°te near Belgrade, where around 40,000 Jews were killed. In all those camps, some 90 percent of the Serbian Jewish population perished. In the Bańćka region annexed by Hungary, numerous Serbs and Jews were killed in 1942 raid by Hungarian authorities. The persecutions against ethnic Serb population occurred in the region of Syrmia, which was controlled by the Independent State of Croatia, and in the region of Banat, which was under direct German control.

Various paramilitary bands resisted Nazi Germany's occupation and division of Yugoslavia from 1941 to 1945, but fought each other and ethnic opponents as much as the invaders. The communist military and political movement headed by Josip Broz Tito (Partisans) took control of Yugoslavia when German and Croatian separatist forces were defeated in 1945. Yugoslavia was among the countries that had the greatest losses in the war: 1,700,000 (10.8 percent of the population) people were killed and national damages were estimated at $9.1-billion.

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

Josip Broz Tito became the president of the new Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Creating one of the most dogmatic of the eastern European communist regimes, Tito and his lieutenants abolished organized opposition, nationalized the means of production, distribution, and exchange, and set up a central planning apparatus. Socialist Yugoslavia was established as a federal state comprising six republics: Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia and Montenegro and two autonomous regions within Serbia‚ÄĒVojvodina and Kosovo and Metohija. The Serbs were both the most numerous and the most widely distributed of the Yugoslav peoples.

Tito forced the collectivization of peasant agriculture (which failed by 1953) while initiating a self-management system which involved a looser system of planning control, with more initiative devolved to enterprises, local authorities, and a decentralized banking structure. A new constitution, in 1963, extended self-management to social services and political administration, and moved the country toward ‚Äúmarket socialism‚ÄĚ by abolishing price controls and requiring enterprises to compete. Once a backward peasant economy, Yugoslavia was transformed into a mid-range industrial country. Yugoslavia became a tourist destination.

Despite this Soviet-style dictatorship, relations with the Soviet Union turned bitter, and in June 1948, Yugoslavia was expelled from the Communist Information Bureau and boycotted by the socialist countries. Tito acquired an international political reputation by supporting the decolonization process and by assuming a leading role in the non-aligned movement.

A movement toward liberalization in the early 1970s was crushed when the ‚ÄúCroatian Spring‚ÄĚ raised a perceived threat that Croatia would secede. The Croatian reformers were purged by 1972, and by 1974 reformers had been ousted in Belgrade. The 1974 constitution, which made Tito president for life, produced a significantly less centralized federation, increasing the autonomy of Yugoslavia's republics as well as the autonomous provinces of Serbia.

After Tito’s death in 1980, authority was vested in a collective presidency made up of representatives of the republics. A rotating presidency led to a further weakening of ties between the republics. During the 1980s the republics pursued significantly different economic policies, with Slovenia and Croatia allowing significant market-based reforms, while Serbia kept to its existing program of state ownership.

But Slovenia, Croatia and the Vojvodina became more prosperous than Serbia, which remained at or about the average in Yugoslav economic indices, while Kosovo, was always at the bottom of the scale. To resolve the disparity, a Federal Fund for the Development of the Underdeveloped Areas of Yugoslavia was set up to redistribute wealth, and enormous amounts of money were redistributed between 1965 and 1988, without noticeable effect. Wealthier regions resented Serbia taking wealth they generated, and resented the use of federal power against republican autonomy. Kosovo’s continued underdevelopment brought the perception that funds were being disbursed more for political reasons.

The break-up of Yugoslavia

By 1983, the unsupervised taking of foreign loans had made Yugoslavia one of the most heavily indebted states of Europe. Yugoslavia's creditors called in the International Monetary Fund, which demanded economic and political liberalization. The Serbian government feared multiparty democracy would split Yugoslavia. Slobodan MiloŇ°evic, a former business official, who from 1986 rose to power through the League of Communists of Serbia, became president of the Serbian Republic in 1989. When Serbia was compelled to hold multiparty elections in December 1990, the League of Communists was renamed the Socialist Party of Serbia, and leader MiloŇ°evic ensured that no opposition could emerge. His party won a large majority in the Skupstina.

But MiloŇ°evic's reluctance to institute a multiparty political system meant that both Serbia and the federation were left behind when other republican governments were re-establishing their roles through popular election. Deepening divisions led to the collapse of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia in January 1990. Serbia backed local Serbs in civil wars hoping to retain some parts of the republics within Yugoslavia. When the Slovene and Croatian governments withdrew from the federation on June 25, 1991, a 10-day war was fought between the Yugoslav Peoples Army (JNA) and Slovene militia and civilian reserves. The clash ended when the Yugoslav army withdrew into Croatia, where the JNA troops fought Croatian paramilitary groups. Germany quickly recognized the new independent states of Slovenia and Croatia.

A Republic of the Serbian Krajina was formed along Croatia‚Äôs border with Bosnia and adjoining the Vojvodina. The Croatian city of Vukovar surrendered to Serb forces in November 1991. In January 1992 a UN-sponsored cease-fire was negotiated. Serb militias carved out several autonomous regions in Bosnia, which were consolidated in March 1992 into the Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina. A war broke out between forces loyal to the government of Bosnia, Croatian units attempting to create a union between Croatia and Croat-majority areas, and a secessionist Serb army. ‚ÄúEthnic cleansing,‚ÄĚ or the practice of depopulating areas of a particular ethnic group, by irregular Serb troops, created a flood of refugees. Serb forces besieged Sarajevo, the Bosnian capital, from May 1992 to December 1995.

Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

A new Federal Republic of Yugoslavia was inaugurated on April 27, 1992, comprising Serbia and Montenegro. It was not recognized by many nations, and tight economic sanctions caused a rapid economic decline. Under MiloŇ°evic's leadership, Serbia led various military campaigns to unite ethnic Serbs in neighboring republics into a "Greater Serbia." These actions led to Yugoslavia being ousted from the UN in 1992, but Serbia continued its ultimately unsuccessful campaign until signing the Dayton Peace Accords in 1995.

MiloŇ°evic and the SPS retained power despite huge opposition in November 1996 elections, although the government conceded that there had been large-scale electoral fraud, provoking months of demonstrations. In July 1997 MiloŇ°evic, barred by the constitution from service as Serbia's president, engineered his election to the federal presidency, and went on to clash with the leadership of Montenegro. On October 5, 2000 after demonstrations and fighting with police, elections were held and he lost to the candidate of the Democratic Opposition of Serbia Vojislav KoŇ°tunica. Following parliamentary elections in January 2001, Zoran ńźinńĎińá became Prime Minister. ńźinńĎińá was assassinated in Belgrade on March 12, 2003. A state of emergency was declared under acting president NataŇ°a Mińáińá. International sanctions were lifted, and MiloŇ°evic was arrested and extradited to The Hague to be prosecuted for war crimes.

Kosovo conflict

Kosovo-Metohija and Vojvodina were given distinctive constitutional status as autonomous regions when the republic was created in 1945. The Muslim Albanians of Kosovo always resisted the ambition of a Yugoslav identity. A revolt had broken out in 1945 in UroŇ°evac in support of the unification of Kosovo with Albania. Thousands of Albanian Muslims were deported to Turkey. From then, the Kosovo problem was contained rather than solved, and containment repeatedly broke down in disorder in 1968, 1981, 1989, and 1998‚Äď99.

In 1989, Ibrahim Rugova, the leader of the Kosovo Albanians, had launched a nonviolent protest against the loss of provincial autonomy. When the autonomy question was not addressed in the Dayton Accords, the Kosovo Liberation Army emerged during 1996. Sporadic attacks on police escalated by 1998 to a substantial armed uprising, which provoked a Serbian attack that resulted in massacres and massive expulsions of ethnic Albanians living in Kosovo. The MiloŇ°evic government's rejection of a proposed settlement led to NATO's bombing of Serbia in the spring of 1999, and to the eventual withdrawal of Serbian military and police forces from Kosovo in June 1999. A United Nations Security Council resolution (1244) in June 1999 authorized the stationing of a NATO-led force (KFOR) in Kosovo to provide a safe environment for the region's ethnic communities, created a UN Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) to foster self-governing institutions, and reserved the issue of Kosovo's final status for an unspecified date in the future.

Serbia and Montenegro

From 2003 to 2006, Serbia was part of the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro, into which the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia had been transformed. A referendum to determine whether or not to end the union with Serbia on May 21, 2006, resulted in independence. On June 5, 2006, the National Assembly of Serbia declared Serbia the legal successor to the state union.

Government and politics

The politics of Serbia take place in a framework of a parliamentary representative democratic republic, whereby the prime minister is the head of government, and of a pluriform multi-party system. The chief of state is the president, who is elected by direct vote for a five-year term and is eligible for a second term. An election was last held in June 2004. Boris Tadic has been the president of Serbia since July 2004, while Fatmir Sejdiu has been the Kosovo president since February 2006.

The prime minister, who is elected by the national assembly, has been Vojislav Kostunica since March 2004). The Kosovo prime minister was Agim Ceku since March 2006. Cabinet ministers are chosen by the national assembly. The unicameral Serbian national assembly has 250 members elected by direct vote for a four-year term. Kosovo has a unicameral assembly of 120 seats, with 100 deputies elected by direct vote, and 20 deputies elected from minority community members, to serve three-year terms. Serbia has a multi-party system, with numerous political parties in which no one party often has a chance of gaining power alone. Political parties must work with each other to form coalition governments. Suffrage is universal to those 18 years of age and over.

The judiciary, which is independent of the executive and the legislature, comprises a constitutional court, a supreme court (to become court of cassation under the new constitution), appellate courts, district courts, municipal courts. Kosovo has a supreme court, district courts, municipal courts, and minor offense courts. The United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) appoints all judges and prosecutors. The legal system is based on a civil law system. Corruption in government and in business is widespread. Political dissidents have been punished harshly.

Administrative subdivisions

The part of Serbia that is neither in Kosovo nor in Vojvodina is often called "Serbia proper." It is not an administrative division, unlike the two autonomous provinces, has no regional government of its own, and is divided into 29 districts plus the City of Belgrade. The districts and the city of Belgrade are further divided into municipalities. The autonomous province of Kosovo and Metohija in the south has five districts and 30 municipalities, which was under United Nations administration in 2007. The autonomous province of Vojvodina in the north has seven districts and 46 municipalities. Negotiations were under way to determine the final status of Kosovo. The Contact Group has postponed the completing of the status process until after Serbian parliamentary elections in January 2007.

Military

The Serbian Armed Forces comprise Land Forces Command (which includes the Serbian naval force, consisting of a river flotilla on the Danube), Joint Operations Command, and Air and Air Defense Forces Command. Peace time service obligation begins at age 17 and lasts until age 60 for men and 50 for women. Under a state of war or impending war, the obligation can begin at age 16 and be extended beyond 60. Conscription was to be abolished in 2010.

Economy

Industry accounts for about 50 percent of Serbia's gross domestic product (GDP) and involves the fabrication of machines, electronics, and consumer goods. Agriculture accounts for 20 percent of GDP. Before World War II, more than 75 percent of the population were farmers. Advances in agricultural technology, reduced this figure to less than 30 percent, including one million subsistence farmers. Crops include wheat, corn, oil, seeds, sugar beets, and fruit. Serbia grows about one-third of the world's raspberries and is the leading frozen fruit exporter. Livestock is raised for dairy products and meat. A quarter of the labor force works in education, government, or services. For more than 150 years, tourists have been coming to Serbian spas - especially Palic and Vrnjacka Banja.

MiloŇ°evic-era mismanagement of the economy, an extended period of economic sanctions, and the damage to Yugoslavia's infrastructure and industry during NATO air strikes in 1999, left the economy only half the size it was in 1990. After MiloŇ°evic was ousted in October 2000, the Democratic Opposition of Serbia coalition government embarked on a market reform program. After renewing its membership in the International Monetary Fund in December 2000, a down-sized Yugoslavia rejoined World Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. A World Bank-European Commission sponsored donors' conference in 2001 raised $1.3-billion for economic restructuring. In November 2001, the Paris Club agreed to reschedule the country's $4.5-billion public debt and wrote off 66 percent of the debt. In July 2004, the London Club of private creditors forgave $1.7-billion of debt just over half the total owed. But aid worth $2-billion pledged in 2001 by the European Union and the United States was delayed because of lack of cooperation by Serbia in handing over General Ratko Mladic to the criminal court in The Hague.

Belgrade has made some progress in privatizing government holdings in energy and telecommunications, and has made some progress towards EU membership. Serbia also sought membership in the World Trade Organization. Unemployment was 31.6 percent (approximately 50 percent in Kosovo), and 30 percent of the population was below the poverty line, and remains an ongoing problem. Kosovo's economy continues to make the transition to a market-based system and is largely dependent on the international community and the diaspora for financial and technical assistance. The complexity of Serbia and Kosovo's political and legal relationships has created uncertainty over property rights and hindered the privatization of state-owned assets in Kosovo. Most of Kosovo's population lives in rural towns, and inefficient, near-subsistence farming is common.

Serbia’s exports totalled $6.428-billion (excluding Kosovo and Montenegro) in 2006. Export commodities included manufactured goods, food and live animals, machinery and transport equipment. Export partners included Italy 14.1 percent, Bosnia and Herzegovina 11.7 percent, Montenegro 10.4 percent, Germany 10.2 percent, and Republic of Macedonia 4.7 percent. Imports totalled $10.58-billion (excluding Kosovo and Montenegro) (2005 est.) Import commodities included oil, natural gas, transport vehicles, cars, machinery, and food. Import partners included Russia 14.5 percent, Germany 8.4 percent, Italy 7.3 percent, People's Republic of China 5 percent, Romania 3 percent.

Per capita gross domestic product (GDP) (purchasing power parity) was $7234, with a rank of 89 on an International Monetary Fund list of 179 nations in 2007.

Demographics

Serbia has several national cultures‚ÄĒSerb culture in the central region, Hungarian language and culture in the northern province of Vojvodina, which borders Hungary, and in Kosovo, an Islamic Albanian culture that bears many remnants of the earlier Turkish conquest. Population statistics, from 2005, showed: Serbia (total) 9,396,411, Vojvodina 2,116,725, Central Serbia 5,479,686, and Kosovo 1,800,000. Life expectancy at birth for the total population was 74 years in 2000.

Ethnicity

| Serbia (excluding Kosovo) in 2002 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serbs | 82.86% | |||

| Hungarians | 3.91% | |||

| Bosniaks | 1.82% | |||

| Roma | 1.44% | |||

| Yugoslavs | 1.08% | |||

| other | 9.79% | |||

Data collected in 2002 showed the ethnic composition of Serbia thus: Serbs 82.86 percent, Hungarians 3.91 percent, Bosniaks 1.82 percent, Roma 1.44 percent, Yugoslavs 1.08 percent, and others (each less than 1 percent) 8.89 percent. Significant minorities include Albanians (who are a majority in the province of Kosovo), Croats, Slovaks, Montenegrins, Macedonians, Bulgarians, and Romanians.

The census was not conducted in Serbia's southern province of Kosovo, which was under administration by the United Nations. Its population comprises 92 percent Albanians, 5.3 percent Serbs, and others form 2.7 percent.

Refugees and internally displaced persons in Serbia form between 7 percent and 7.5 percent of its population. With over half a million refugees (from Croatia mainly, to an extent Bosnia and Herzegovina too and internally displaced personal from Kosovo), Serbia takes the first place in Europe with the largest refugee crisis, as a result of the Yugoslav wars.

Religion

| Serbia (excluding Kosovo) in 2002 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| religion | percent | |||

| Eastern Orthodoxy | 84.1% | |||

| Roman Catholicism | 6.24% | |||

| Islam | 4.82% | |||

| Protestantism | 1.44% | |||

According to the 2002 Census, 82 percent of the population of Serbia (excluding Kosovo) or were overwhelmingly adherents of the Serbian Orthodox Church. Other Orthodox Christian communities in Serbia include Montenegrins, Romanians, Macedonians, Bulgarians, and Vlachs. Together they comprise about 84 percent of the entire population.

Catholicism is mostly present in Vojvodina (mainly in its northern part), where almost 20 percent of the regional population (belonging to different ethnic groups such as the Hungarians, Slovaks, Croats, Bunjevci, and Czechs) belong to this denomination. There are an estimated 433,000 baptized Catholics in Serbia, roughly 6.2 percent of the population, mostly bounded to the northern province and Belgrade area. Protestantism accounts for about 1.5 percent of the country's population.

Islam has a strong following in south Serbia - the Raska region, several municipalities in the south-east, and especially in Kosovo. Bosniaks are the largest Muslim community in Serbia (excluding Kosovo) at about (2 percent), followed by Albanians (1 percent), Turks, and Arabs.

The Eastern Orthodox Church split from the Roman Catholic Church in 1054, in what became known as the Great Schism, involving the authority of the pope, which the Eastern Orthodox religion does not recognize. The Serbian Orthodox Church was founded in 1219, and its rise was tied to the rise of the Serbian state. A central figure in the church is Saint Sava, the brother of Stefan Nemanja, Serbia's first king. The church has promoted Serbian nationalism, and has struggled against the dominance of the central authority of the Greek Orthodox Church in Constantinople.

The exile of Jews from Spain after the Alhambra Decree in 1492, which ordered all Jews to leave, meant that thousands of individuals and families made their way through Europe to the Balkans. Many settled in Serbia, and most assimilated. The Jewish population shrunk from 64,405 in 1931 to 6835 in 1948. Many of those who were not killed in the Holocaust emigrated to Israel. By the year 2007, the Jewish population was about 5000, organized into 29 communes under the Federation of Jewish Communities in Yugoslavia.

Language

The Serbian language, which is the official language of Serbia, is one of the standard versions of the Shtokavian dialect, used primarily in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Croatia, and by Serbs in the Serbian diaspora. The former standard is known as Serbo-Croatian, now split into Serbian, Croatian and Bosnian standards. Two alphabets are used to write the Serbian language: a Serbian Cyrillic variation on the Cyrillic alphabet, and a variation on the Latin alphabet.

The Ekavian variant of the Shtokavian dialect is spoken mostly in Serbia and Ijekavian in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, south-western Serbia, and Croatia. The base for the Ijekavian dialect is East-Herzegovinian, and of the Ekavian, the ҆umadija-Vojvodina dialect.

Other languages spoken in Serbia include Romanian, Hungarian, Slovak, Ukrainian, and Croatian, all of which are official languages in Vojvodina. Albanian is the official language of Kosovo.

Men and women

While traditionally women performed only domestic work, under communism the number of women wage earners increased from 400,000 in 1948 to 2.4 million in 1985. Women work in social welfare, public service and administration, and trade and catering, as well as teachers in elementary schools. Serbian culture is male-dominated‚ÄĒmen head the household, while women are expected to cook, clean, and take care of other domestic tasks.

Marriage and the family

Serbians generally choose their own partners. Wedding celebrations can last for days. Traditionally, before a couple enters their new house, the bride stands in the doorway and lifts a baby boy three times, to ensure their marriage will produce children. The domestic unit is commonly the extended family. In Serbian families, cousins, aunts, uncles, and other family members live in close proximity. Ethnic Albanians tend to have large families, and extended families often live together in a group of houses enclosed by a stone wall. During the communist era, women gained equal rights in marriage, and divorce became easier and more common. The first-born son inherits the family's property.

A traditional kin group was the zadruga, a group of a hundred or more people made up of extended families which, in rural areas, organized farm work. Each zadruga had its own patron saint, and provided for orphans, the elderly, and the sick or disabled. The mother takes care of the children, although godparents play a significant role, and there is a ceremony upon birth that involves the godparent cutting the child's umbilical cord. The godparent is in charge of naming the baby, has a role of honor in the baptism, and later in the child's wedding, and is responsible for the child if anything happens to the parents. Day nurseries to care for babies, allowing women to return to their jobs soon after childbirth, appeared during the communist era. Both boys and girls help with household chores.

Education

Education starts in either pre-schools or elementary schools. Children enroll in elementary schools at the age of seven and attend for eight years. Secondary schools are divided in three types, and children attend one depending on their choice, their elementary school grades and their entrance exams results:

- Grammar schools (gimnazija) last for four years and offer general and broad education. Student usually choose their education orientation between languages and social sciences (druŇ°tveni smer) and mathematics and natural sciences(prirodni smer).

- Professional schools (struńćna Ň°kola) last for four years and specialize students in certain fields, while still offering relatively broad education.

- Vocational schools (zanatska Ň°kola) last for three years, without an option of continuing education and specialize in narrow vocations.

Tertiary level institutions accept students based on their grades in high school and entrance exams results:

- Higher schools (viŇ°a Ň°kola), corresponding to American colleges, which lasts between two and four years.

- Universities and art academies, which last between four and six years (one year is two semesters long), and which grant diplomas equivalent to a Bachelor of Arts or a Diploma in Engineering (for study in the field of technical sciences) degree.

Graduate education is offered after tertiary level, and Master's degrees and Ph.Ds are awarded. The largest university, in Belgrade, was founded in 1863. The University of Belgrade is one of the largest universities in the Balkan region counting over 78,000 students, 1700 postgraduate students, 2500 teaching staff, 31 faculties, and eight scientific research institutes. There are other universities in the cities of Novi Sad, Nis, Podgorica, and Pristina.

In 2002, 96.4 percent of the total population aged 15 and over could read and write.

Class

Before World War II, Serbia had a large peasant class, a tiny middle class, and a small upper class comprising government workers, professionals, merchants, and artisans. Education, party membership, and rapid industrialization under the communist regime hastened upward mobility, and increased numbers in the middle and ruling classes. The free-market economy since the end of the Tito communist era has enabled people to improve their status through entrepreneurship, although economic sanctions decreased the overall standard of living, and exacerbated the differences between the rich and poor.

Culture

The Byzantine Empire, the Serb Orthodox Church, and Serbian peasant culture have influenced Serbian arts, crafts and music. Serbian culture fell into decline during five centuries of rule under the Ottoman Empire. Following autonomy and eventual independence in the nineteenth century, there was a resurgence of Serbian culture. Socialist Realism was dominated official art during the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia although influence from the West as well as traditional culture has increased. While the north is culturally Central European, the south is rather more Oriental.

Architecture

Serbia is famous for its huge, beautiful churches and monasteries located in the big cities, and scattered throughout the nation. They are awe-inspiring structures adorned with elaborate mosaics, frescoes, and marble carvings. The most distinctive piece of medieval Serbian architecture was the Studenica monastery founded by Stefan Nemanja, the founder of medieval Serbia. Studenica monastery was the model for other monasteries at MileŇ°eva, Sopońáani, and the Visoki Deńćani.

Belgrade has the old royal palace of Yugoslavia, and has centuries-old churches, mosques, and several national museums. An area called New Belgrade was built on the outskirts of the city. Belgrade has been captured 60 times (by the Romans, Huns, Turks, and Germans, among others) and destroyed 38 times, and many of the city's older structures were damaged by the Nazis during World War II. Some were later restored, but the recent civil war has again devastated the city.

Most city dwellers live in apartment buildings. Rural houses are modest buildings of wood, brick, or stone, have courtyards enclosed by walls or fences for privacy, and are built close together. Some Kosovo villages are laid out in a square pattern, have watchtowers, and are surrounded by mud walls for protection.

Art

Art in Serbia is most visible in the numerous religious buildings throughout the country. Studenica monastery has Byzantine style fresco paintings, and extensive sculptures based on Psalms and the Dormition of the Theotokos, a great feast of the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Eastern Catholic churches, which commemorates the "falling asleep" or death of Mary, the mother of Jesus. After the capture of Constantinople in 1204, many Greek artists fled to Serbia. Their influence can be seen at the Church of the Ascension at MileŇ°eva as well as in the wall paintings at the Church of the Holy Apostles at Peńá, and at the Sopońáani Monastery. Icons form a significant part of church art, as do manuscripts. Miroslav's Gospel features lavish calligraphy and miniatures, as does the Chludov Psalter dating from the fourteenth century.

The Ottoman conquest of Serbia in 1459 meant that since the church was not recognised and the nobility was persecuted, the main source of patronage for architects and artists dried up. There a resurgence in art in the nineteenth century as Serbia gradually regained its autonomy. Serbian paintings showed the influence of Neoclassicism and Romanticism. Anastas Jovanovińá was a pioneering photographer in Serbia, taking the photos of many leading citizens. Kirilo Kutlik set up the first school of art there in 1895. Many of his students went to study in Western Europe, and brought back avant-garde styles. NadeŇĺda Petrovińá was influenced by Fauvism while Sava ҆umanovińá worked in Cubism.

After World War I, the Belgrade School of Painting developed including Milan Konjovińá working in a Fauvist manner, and Marko ńĆelebonovińá working in a style called Intimisme. Yovan Radenkovitch (1901-1979) left Belgrade for Paris in the 1930s, befriending Matisse and Vlaminck, and adopted a style inspired by Fauvism.

Socialist realism was the dominant school after World War II with the rise to power of the Communist Party under Tito. During the 1960s, Serbian artists, led by Petar Lubarda and Milo Milunovińá, started to break free from the constraints of socialist realism. The Mediala group featuring Vladimir Velińćkovińá was formed in the 1970s to promote Surrealist figurative painting.

Serbia is known for textiles made of wool, flax, and hemp, which are woven into carpets of complex geometric patterns. Another traditional art form is the decoration of Easter eggs, colored with natural dyes and adorned with intricate patterns and designs.

Cuisine

Traditional Serbian cuisine has been influenced by Turkish and Greek traditions. ńÜevapi, consisting of grilled heavily seasoned mixed ground meat patties, is considered to be the national dish. Other notable dishes include koljivo, boiled wheat which is used in religious rituals, Serbian salad, sarma (stuffed cabbage), podvarak (roast meat with sauerkraut) and moussaka. ńĆesnica is a traditional bread for Christmas Day.

Bread is the basis of Serbian meals and it is often treated almost ritually. A traditional Serbian welcome is to offer the guest bread and salt. Bread plays an important role in Serbian religious rituals. Some people believe that it is sinful to throw away bread regardless of how old it is. Although pasta, rice, potato, and similar side dishes did enter the everyday cuisine, many Serbs still eat bread with these meals. White wheat bread loafs (typically 600 grams) are sold. Black bread and various high fiber whole wheat bread variations regained popularity as a part of more healthy diets. In rural households, bread is baked in ovens at home, usually in bigger loafs.

Breakfast in Serbia is an early but hearty meal. Tea, milk, or strong coffee is served, with pastries or bread, which are served with butter, jam, yoghurt, sour cream and cheese, accompanied by bacon, sausages, salami, scrambled eggs and kajmak, a creamy dairy product similar to clotted cream.

Soups are the most frequent first course, mostly simple pottages made of beef or poultry with added noodles. Popular competitions exist for the preparation of fish soup (riblja ńćorba).

Barbecue is popular, and makes the main course in most restaurants. It is often eaten as fast food. Varieties include pljeskavica (hamburger), ńÜevapńćińái (small kebabs), veŇ°alica (strips of smoked meat), various sausages, meŇ°ano meso (mixed grill), and raŇĺnjińái (skewered kabobs).

Slivovitz, a distilled fermented plum juice is the national drink of Serbia with 70 percent of domestic plum production being used to make it. Domestic wines are popular. Turkish coffee is widely drunk as well. Vrzole wine is made by private winery Vinik from famous wine region - Vrsac. Winery Vinik blends traditional family recipes and newest technology in making limited quantities of this famous red and white wine.

Customs and etiquette

Kissing, with three kisses on alternate cheeks, is a common greeting for men and women. When entering a home as a guest for the first time, one brings a gift of flowers, food, or wine. It is customary to remove one's shoes upon entry. Hosts serve their guests.

Clothing

Young people and city-dwellers wear Western-style clothing, while in the villages, women wear a plain blouse, long black skirt, and head scarf. Unmarried women wear small red felt caps decorated with gold braid for festive occasions, and married women wear large white hats with starched wings. Albanian men in Kosovo wear small white Muslim caps.

Literature

Miroslav's Gospel is one of the earliest works of Serbian literature, dating from between 1180 and 1191, and one of the most important works of the medieval period. Serbian epic poetry was a central part of medieval Serbian literature based on historic events such as the Battle of Kosovo. Literature declined following occupation by the Ottoman Empire in 1459. Dositej Obradovińá was a notable writer during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Vuk Stefanovińá KaradŇĺińá played a central role in the Serbian literary resurgence of the nineteenth century, by collecting folk songs and poems and publishing them in a book. Petar II Petrovińá NjegoŇ° was the most notable of poets continuing the epic tradition notably in his poem Mountain Wreath published in 1847. Serbian literature flourished further in the twentieth century. Ivo Andrińá received the Nobel prize for literature in 1961 for his 1945 novel The Bridge on the Drina. Danilo KiŇ° established his reputation with his work A Tomb for Boris Davidovich published in 1976 and commenting on Yugoslav politics. Other notable authors include MeŇ°a Selimovińá, MiloŇ° Crnjanski, Borislav Pekińá, Milorad Pavińá, Dobrica ńÜosińá, and David Albahari.

Music

Serbian music dates from the medieval period, based on the Osmoglasnik a cycle of religious songs based on the resurrection and lasting for eight weeks. During the Nemanjic dynasty, musicians enjoyed royal patronage. There was also a strong folk tradition in Serbia dating from this time. Medieval musical instruments included horns, trumpets, lutes, psalteries, drums, and cymbals. Traditional folk instruments include various kinds of bagpipes, flutes, diple, and tamburitza, among others. With the beginning of Turkish rule, new instruments like the zurle, kaval, and tapan were introduced.

During [Ottoman]] rule, Serbs were denied the use of musical instruments. Church music had to performed in private. The gusle, a one-stringed instrument, was invented by Serbian peasants during this time. Filip ViŇ°njińá was a particularly notable guslar (gusle player). Folk music resurged in the nineteenth century. Jozip Slezenger founded the Prince's Band playing music based on traditional tunes. Stevan Mokranjac, a composer and musicologist collected folk songs, and was the director of the first Serbian School of Music and one of the founders of the Union of Singing Societies. His most famous works are the Song Wreaths. Kornilije Stankovic wrote the first Serbian-language works for choirs.

Brass bands are popular, especially in southern and central Serbia. This tradition is dominated by Gypsy musicians. Fejat Sejdińá, Bakija Bakińá, and Boban Markovińá are the biggest names in modern brass band bandleaders.

The "Golden age" of Yugoslav rock music occurred during 1980s when Belgrade's New Wave music bands, such as Idoli, ҆arlo Akrobata, and Elektrińćni orgazam. Turbo-folk combined Western rock and pop styles with traditional folk music vocals. Serbian immigrants have taken their musical traditions to nations such as the United States and Canada.

In 2007, the most famous mainstream performers include Riblja ńćorba, known for political statements in their music, Bajaga i Instruktori and Van Gogh, while Rambo Amadeus and Darkwood Dub are the most prominent musicians of the alternative rock scene. There are also numerous hip-hop bands and artists, mostly from Belgrade including GRU (hip-hop), 187, C-Ya, and Beogradski Sindikat.

Newer pop artists include Vlado Georgiev, Negative, NataŇ°a Bekvalac, Tanja Savic, Ana Stanińá, Night Shift, and ŇĹeljko Joksimovińá, who was runner-up in the Eurovision Song Contest 2004. Marija ҆erifovińá won the Eurovision Song Contest 2007 with "Prayer." Serbia will host the 2008 contest.

Dance

Pure folk music includes a two-beat circle dance called the kolo, which has almost no movement above the waist. During Ottoman rule, when people were forbidden to hold large celebrations, they often transmitted news through the lyrics and movements of the kolo tradition. Traditional accompaniment to the dance is a violin, and occasionally an accordion or a flute. Costumes are important. Traditional regional dress is worn for the performances.

Theatre and cinema

Serbia has numerous theatres, including the Serbian National Theatre, which was established in 1861. The company started performing opera from the end of the nineteenth century and the permanent opera was established in 1947. It established a ballet company.

The Belgrade International Theatre Festival (Bitef) is one of the oldest such festivals in the world. New Theatre Tendencies is the constant subtitle of the festival. Founded in 1967, Bitef has continually followed and supported the latest theater trends. It has become one of five most important and biggest European festivals.

Serbia had 12 films produced before the start of World War II‚ÄĒthe most notable was Mihail Popovic's The Battle of Kosovo in 1939. Cinema prospered after World War II. The most notable postwar director was DuŇ°an Makavejev who was internationally recognised for Love Affair: Or the Case of the Missing Switchboard Operator in 1969, focussing on Yugoslav politics. Makavejev's Montenegro was made in Sweden in 1981. Zoran Radmilovic was one of the most notable actors of the postwar period.

Some 1990s movies took on the difficult subject of the civil war, including Pretty Village, Pretty Flame, directed by Srdjan Dragojevic. Goran Paskaljevic produced the widely acclaimed film Powder Keg in 1998. Emir Kusturica won a Golden Palm for Best Feature Film at the Cannes Film Festival for Underground in 1995, and in 1998, won a Silver Lion for directing Black Cat, White Cat.

As at 2001, there were 167 cinemas in Serbia (excluding Kosovo and Metohija) and over 4 million Serbs went to the cinema in that year. In 2005, San zimske nońái (A Midwinter Night's Dream ) directed by Goran Paskaljevińá] caused controversy over its criticism of Serbia's role in the Yugoslav wars in the 1990s.

Sports

Recreational activities and sports are well developed, with hundreds of thousands of individuals registered as active participants in sports organizations. Hunting and fishing are particularly popular, although much sport activity revolves around team sports: football (soccer), basketball, water polo, volleyball, handball, gymnastics, martial arts, and rugby football. Serbia has produced a number of notable players who have competed for the top football clubs of Europe, and Crvena Zvezda Beograd (Red Star Belgrade) is one of the sport's legendary teams.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Error on call to template:cite web: Parameters url and title must be specified (in Serbian).

- ‚ÜĎ Census 2011. –†–ó–°; Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- ‚ÜĎ 3.0 3.1 3.2 IMF World Economic Outlook Database, September 2011. International Monetary Fund (2011). Retrieved October 31, 2011.

Sources and Further reading

- Allcock, John B., Marko Milivojevińá, and John J. Horton. 1998. Conflict in the former Yugoslavia: an encyclopedia. (Roots of modern conflict.) Denver, CO: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 0874369355

- Anzulovic, Branimir. 1999. Heavenly Serbia: from myth to genocide. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0814706711

- Burton, Kim. "Balkan Beats." 2000. Broughton, Simon; Ellingham, Mark; McConnachie, James; Duane, Orla. World Music, Vol. 1: Africa, Europe and the Middle East. 273-276. Rough Guides Ltd, Penguin Books. ISBN 1858286360

- Campbell, Greg. 1999. The road to Kosovo: a Balkan diary. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 0813335892

- Popov, NebojŇ°a, and Drinka Gojkovińá. 2000. The road to war in Serbia: trauma and catharsis. Budapest: Central European University Press. ISBN 9639116564

- Hawkesworth, Celia. 2000. Voices in the shadows women and verbal art in Serbia and Bosnia. New York: Central European University Press. ISBN 0585395314

- Lampe, John R. 1996. Yugoslavia as history: twice there was a country. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521461227

- Milivojevic, JoAnn. 1999. Serbia. Enchantment of the world. New York: Children's Press. ISBN 051621196X

- Wachtel, Andrew. 1998. Making a nation, breaking a nation: literature and cultural politics in Yugoslavia. Cultural memory in the present. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0804731802

External links

All links retrieved January 26, 2023.

- Countries and Their Cultures. Culture of Serbia and Montenegro.

- British Broadcasting Corporation. Country profile: Serbia.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Serbia  history

- Kosovo  history

- Geography_of_Serbia  history

- Belgrade  history

- History_of_Serbia  history

- Politics_of_Serbia  history

- Economy_of_Serbia  history

- Dormition_of_the_Theotokos  history

- Demographics_of_Serbia  history

- Serbian_culture  history

- Serbian_language  history

- Tourism_in_Serbia  history

- Music_of_Serbia  history

- Serbian_cuisine  history

- Serbian_art  history

- Studenica_monastery  history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.