Constantinople

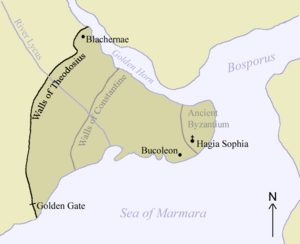

Constantinople (Greek: Κωνσταντινούπολη) was the capital of the Byzantine Empire and, following its fall in 1453, of the Ottoman Empire until 1930, when it was renamed Istanbul as part of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's Turkish national reforms. Strategically located between the Golden Horn and the Sea of Marmara at the point where Europe meets Asia, Constantinople was extremely important as the successor to ancient Rome and the largest and wealthiest city in Europe throughout the Middle Ages, it was known as the "Queen of Cities."

The city has had many names throughout history. Depending on the background of people, and their language and ethnicity, it often had several different names at any given time; among the most common were Byzantium, New Rome, Constantinople and Stamboul. Usually, the name Constantinople refers to the period from its founding by Constantine I to the Muslim conquest.

Loss of Constantinople sent shock waves throughout Europe. Soon afterwards, the Balkans fell to the Ottomans. Although important commerical ties with Stamboul continued, Europeans never forgave the Turks for seizing Europe's remaining link to the Roman world that had shaped Europe's administrative and legal systems and which, through the Catholic tradition, continued to inform her Christian faith. Turks and Muslims were demonized as the other, who opposed progress and the true faith. No effort was made to enquire whether God's voice might also be speaking through their religion. Europe continued to mourn the loss of Constantinople, yet Europeans had not been consistent friends of the city they claimed to hold in such high esteem.

Before and after

The city was originally founded in the early days of Greek colonial expansion, when in 667 B.C.E. the legendary Byzas established it with a group of citizens from the town of Megara. This city was named Byzantium (Greek: Βυζάντιον) after its founder. Constantine I's later foundation of the new city on this site (and subsequent renaming in his honor) on May 11, 330 C.E. reflected its strategic and commercial importance from the earliest times, lying as it does astride both the land route from Europe to Asia and the seaway from the Black or Euxine Sea to the Mediterranean, whilst also possessing an excellent and spacious harbor in the Golden Horn. Many features of the new city of Constantine were copied from Rome, and it is sometimes called 'New Rome' (Nova Roma), although there is no evidence that this was ever an official title in Constantine's time.

After a great developmental period, Constantinople and the empire fell to the Ottoman Empire on May 29, 1453, during the reign of Constantine XI Paleologus. Although the Turks overthrew the Byzantines, Fatih Sultan Mehmed the Second (the Ottoman Sultan at the time) styled himself as the next Roman emperor ("Kayser-i-Rum") and let the Orthodox Patriarchy continue to conduct their own affairs, having stated that they did not want to join the Vatican. However, this did not stop him from ordering the conversion of the city's central church, Hagia Sophia, into a mosque, and having a Muslim scholar decree from its pulpit that "there is no god but Allah." Following the Turkish conquest all Christians not killed or sold into slavery were relegated to the status of dhimmis.

History

There are several distinct periods in the history of the city.

Constantine, 306-363

Constantine I had ambitious plans. Having restored the unity of the empire, now overseeing the progress of major governmental reforms and sponsoring the consolidation of the Christian church, Constantine was well aware that Rome had become an unsatisfactory capital for several reasons. Located in central Italy, Rome lay too far from the eastern imperial frontiers, and hence also from the legions and the Imperial courts. Moreover, Rome offered an undesirable playground for disaffected politicians; it also suffered regularly from flooding and from malaria.

It seemed impossible to many that the capital could be moved. Nevertheless, Constantine identified the site of Byzantium as the correct place: a city where an emperor could sit, readily defended, with easy access to the Danube or the Euphrates frontiers, his court supplied from the rich gardens and sophisticated workshops of Roman Asia, his treasuries filled by the wealthiest provinces of the empire.

Constantine laid out the expanded city, dividing it into 14 regions, and ornamenting it with great public works worthy of a great imperial city. Yet initially Constantinople did not have all the dignities of Rome, possessing a proconsul, rather than a prefect of the city. Furthermore, it had no praetors, tribunes, or quaestors. Although Constantinople did have senators, they held the title clarus, not clarissimus, like those of Rome. Constantinople also lacked the panoply of other administrative offices regulating the food supply, police, statues, temples, sewers, aqueducts, or other public works. The new program of building was carried out in great haste: columns, marbles, doors, and tiles were taken wholesale from the temples of the empire and moved to the new city. Similarly, many of the greatest works of Greek and Roman art were soon to be seen in its squares and streets. The emperor stimulated private building by promising householders gifts of land from the imperial estates in Asiana and Pontica, and on May 18, 332 C.E. he announced that, as in Rome, free distributions of food would be made to citizens. At the time the amount is said to have been 80,000 rations a day, doled out from 117 distribution points around the city.

Constantinople was a Greek Orthodox Christian city, lying in the most Christianized part of the Empire. Justinian (483-565 C.E.) ordered the Pagan temples of Byzantium to be deconstructed, and erected the splendid Church of the Holy Wisdom, Sancta Sophia (also known as Hagia Sophia in Greek), as the centerpiece of his Christian capital. He oversaw also the building of the Church of the Holy Apostles, and that of Hagia Irene.

Constantine laid out anew the square at the middle of old Byzantium, naming it the Augusteum. Sancta Sophia lay on the north side of the Augusteum. The new senate-house (or Curia) was housed in a basilica on the east side. On the south side of the great square was erected the Great Palace of the emperor with its imposing entrance, the Chalke, and its ceremonial suite known as the Palace of Daphne. Located immediately nearby was the vast Hippodrome for chariot races, seating over 80,000 spectators, and the Baths of Zeuxippus (both originally built in the time of Septimius Severus). At the entrance at the western end of the Augusteum was the Milion, a vaulted monument from which distances were measured across the Eastern Empire.

From the Augusteum a great street, the Mese, led, lined with colonnades. As it descended the First Hill of the city and climbed the Second Hill, it passed on the left the Praetorium or law-court. Then it passed through the oval Forum of Constantine where there was a second senate-house, then on and through the Forum of Taurus and then the Forum of Bous, and finally up the Sixth Hill and through to the Golden Gate on the Propontis. The Mese would be seven Roman miles long to the Golden Gate of the Walls of Theodosius.

Constantine erected a high column in the middle of the Forum, on the Second Hill, with a statue of himself at the top, crowned with a halo of seven rays and looking towards the rising sun.

Divided empire, 363-527

The first known prefect of the City of Constantinople was Honoratus, who took office on December 11, 359 and held it until 361 C.E. Emperor Valens built the Palace of Hebdomon on the shore of the Propontis near the Golden Gate, probably for use when reviewing troops. All the emperors who were elevated at Constantinople, up to Zeno and Basiliscus, were crowned and acclaimed at the Hebdomon. Theodosius I founded the church of John the Baptist to house the skull of the saint, put up a memorial pillar to himself in the Forum of Taurus, and turned the ruined temple of Aphrodite into a coach house for the Praetorian Prefect; Arcadius built a new forum named after himself on the Mese, near the walls of Constantine.

Gradually the importance of the city increased. Following the shock of the Battle of Adrianople in 376 C.E., when the emperor Valens with the flower of the Roman armies was destroyed by the Goths within a few days' march of the city, Constantinople looked to its defenses, and Theodosius II built in 413-414 the 60-foot tall walls which were never to be breached until the coming of gunpowder. Theodosius also founded a university at the Capitolium near the Forum of Taurus, on February 27, 425.

In the fifth century C.E., the Huns, led by Attila, demanded tribute from Constantinople. The city refused to pay, and Attila was about to wage conquest upon the city when a message from Honoria, a sister of Valentinian III, was interpreted by Attila as a marriage proposal, so instead of laying siege to Constantinople, Attila redirected his raiders' assault on the Western Roman Empire, namely in Gaul, Orléans, and Rome.

Just a few years later, when the barbarians overran the Western Empire, its emperors retreated to Ravenna before it collapsed altogether. Thereafter, Constantinople became in truth the largest city of the Empire and of the world. Emperors were no longer peripatetic between various court capitals and palaces. They remained in their palace in the Great City, and sent generals to command their armies. The wealth of the Eastern Mediterranean and Western Asia flowed into Constantinople.

Justinian 527-565

Emperor Justinian I (527-565 C.E.) was known for his successes in war, for his legal reforms, and for his public works. It was from Constantinople that his expedition for the reconquest of Africa set sail on or about 21 June 533 C.E. Before their departure the ship of the commander, Belisarius, anchored in front of the Imperial palace, and the Patriarch offered prayers for the success of the enterprise.

Chariot-racing had been important in Rome for centuries. In Constantinople, the hippodrome became over time increasingly a place of political significance. It was where (as a shadow of the popular elections of old Rome) the people by acclamation showed their approval of a new emperor; and also where they openly criticized the government, or clamoured for the removal of unpopular ministers. In the time of Justinian, public order in Constantinople became a critical political issue. The entire late Roman and early Byzantine period was one where Christianity was resolving fundamental questions of identity, and the dispute between the orthodox and the monophysites became the cause of serious disorder, expressed through allegiance to the horse-racing parties of the Blues and the Greens, and in the form of a major rebellion in the capital of 532 C.E., known as the "Nika" riots (from the battle-cry of "Victory!" of those involved).

Fires started by the Nika rioters consumed the basilica of St Sophia, the city's principal church originally built by Constantine I. Justinian commissioned Anthemius of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus to replace it with the incomparable St Sophia, the great cathedral of the Orthodox Church, whose dome was said to be held aloft by God alone, and which was directly connected to the palace so that the imperial family could attend services without passing through the streets (St Sophia was converted into a mosque after the Ottoman conquest of the city, and is now a museum). The dedication took place on December 26 537 C.E. in the presence of the emperor, who exclaimed, "O Solomon, I have outdone thee!"[1]

Justinian also had Anthemius and Isidore demolish and replace the original Church of the Holy Apostles, built by Constantine, with a new church under the same dedication. This was designed in the form of an equally-armed cross with five domes, and ornamented with beautiful mosaics. This church was to remain the burial place of the emperors from Constantine himself until the eleventh century. When the city fell to the Turks in 1453 C.E., the church was demolished to make room for the tomb of Mehmet II the Conqueror.

Survival, 565-717

Justinian was succeeded in turn by Justin II, Tiberius II, and Maurice, able emperors who had to deal with a deteriorating military situation, especially on the eastern frontier. Maurice reorganized the remaining Byzantine possessions in the west into two Exarchates, the Exarchate of Ravenna and the Exarchate of Carthage. Maurice increased the Exarchates' self-defense capabilities and delegated them to civil authorities. Subsequently there was a period of near-anarchy, which was exploited by the enemies of the empire.

In the early seventh century, the Avars and later the Bulgars overwhelmed much of the Balkans, threatening Constantinople from the west. Simultaneously, Persians from the east, the Sassanids, invaded and conquered Egypt, Palestine, Syria and Armenia. Heraclius, the exarch of Carthage, set sail for the city and assumed the purple. Heraclius accepted the Hellenization of Constantinople and the Eastern Empire by replacing Latin with Greek as its language of government. However, he found the military situation so dire that at first he contemplated moving the imperial capital to Carthage, but the people of Constantinople begged him to stay. He relented, and while Constantinople withstood a siege by the Avars and Persians, Heraclius launched a spectacular campaign into the heart of the Persian Empire. The Persians were defeated outside Nineveh, and their capital at Ctesiphon was surrounded by the Byzantines. Persian resistance collapsed, and all the lost territories were recovered in 627 C.E.

However, the unexpected appearance of the newly-converted and united Muslim Arabs took the territories by surprise from an empire exhausted from fighting against Persia, and the southern provinces were overrun. Byzantine Mesopotamia, Syria, Egypt, and North Africa were permanently incorporated into the Muslim empire in the seventh century, a process which was completed with the fall of Carthage to the caliphate in 698 C.E.

Meanwhile, at much the same time, Lombard invaders were expanding across northern Italy, taking Liguria in 640 C.E. By the middle of the eighth century, the Exarchate of Ravenna had been lost, leaving the Byzantines with control of only small areas around the toe and heel of Italy, plus some semi-independent coastal cities like Venice, Naples, Amalfi and, Gaeta.

Constantinople was besieged twice by the Arabs, once in a long blockade between 674 and 678 C.E., and in 717 C.E. The Second Arab siege of Constantinople (717-718 C.E.) was a combined land and sea effort by the Arabs to take Constantinople. The Arab ground forces, led by Maslama, were annihilated by a combination of failure against the city's impregnable walls, the stout resistance of the defenders, freezing winter temperatures, chronic outbreaks of disease, starvation, and ferocious Bulgarian attacks on their camp. Meanwhile, their naval fleet was decimated by the Greek Fire of the Byzantine Navy, and the remnants of it were subsequently utterly destroyed in a storm on the return home. The crushing victory of the Byzantines was a severe blow to Caliph Umar II, and the expansion of the Umayyad Caliphate was severely stunted during his reign.

Recovery, 717-1025

For the Byzantines, the victory at Constantinople was an epic triumph; they had turned back the tide of Islamic expansion, ensuring the survival of Christianity. They had also inadvertently saved the rest of Europe in the process. A long period of Byzantine retreat came to an end, and the imperial frontier in the east became fixed on the Taurus–Anti-Taurus mountain range in eastern Asia Minor, where it would remain unchanged for the next two hundred years.

Asia Minor became the heartland of the empire, and from this time onwards the Byzantines began a recovery that resulted to the recovery of parts of Greece, Macedonia and Thrace by the year 814 C.E. By the early years of the eleventh century, the Bulgarian Khanate had been utterly destroyed and annexed to the empire, the Slavs and the Rus had converted to Orthodoxy.

In Italy, the emperor Basil I (867-886) conquered the whole of the south, restoring Byzantine power on the mainland to a position stronger than at any time since the seventh century.

In the east, the imperial armies began a major advance during the tenth and eleventh centuries, resulting in the recovery of Crete, Cyprus, Cilicia, Armenia, eastern Anatolia and northern Syria, and the reconquest of the Holy city of Antioch.

The Iconoclast controversy, 730-787, 814-842

In the eighth and ninth centuries the iconoclast movement caused serious political unrest throughout the Empire. The emperor Leo III issued a decree in 726 C.E. against images, and ordered the destruction of a statue of Christ over one of the doors of the Chalke, an act which was fiercely resisted by the citizens. Constantine V convoked a church council in 754 C.E. which condemned the worship of images, after which many treasures were broken, burned, or painted over. Following the death of his son Leo IV the Khazar in 780 C.E., the empress Irene restored the veneration of images through the agency of the Second Council of Nicaea in 787 C.E.

The iconoclast controversy returned in the early ninth century, only to be resolved once more in 843 during the regency of Empress Theodora, who restored the icons. These controversies further contributed to the disintegrating relations with the Roman Catholic Church and the Holy Roman Empire, both of which continued to increase their independence and power.

Prelude to the Komnenian period 1025–1081

In the late eleventh century, catastrophe struck the Byzantine Empire. With the imperial armies weakened by years of insufficient funding and civil warfare, Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes suffered a surprise defeat at the hands of Alp Arslan (sultan of the Seljuk Turks) at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071 C.E. This was due to treachery from his allies who deserted him on the field of battle, and the neglected state of the army which he inherited from his predecessors. Romanus was captured, and although the Sultan's peace terms were not excessive, the battle was catastrophic for the Byzantine Empire.

On his release, Romanus found that his enemies had conspired against him to place their own candidate on the throne in his absence. Romanus surrendered and suffered a horrific death by torture. The new ruler, Michael VII Doukas, refused to honour the treaty that had been signed by Romanus. In response, the Turks began to move into Anatolia in 1073 C.E., while the collapse of the old defensive system meant that they met no opposition. To make matters worse, chaos reigned as the empire's remaining resources were squandered in a series of disastrous civil wars. Thousands of Turkoman tribesmen crossed the unguarded frontier and moved into Anatolia. By 1080 an area of 30,000 square miles had been lost to the empire, and the Turks were within striking distance of Constantinople.

The Komnenoi 1081-1180

Under the Komnenian dynasty (1081-1185), Byzantium staged a remarkable military, financial and territorial recovery. This is sometimes called the Komnenian restoration, and is closely linked to the establishment of the Komnenian army, the new military system of this period.

In response to a call for aid from Alexios I Komnenos, the First Crusade assembled at Constantinople in 1096 C.E. and set out for Jerusalem. Much of this is documented by the writer and historian Anna Comnena in her work The Alexiad. The Crusaders agreed to return any Byzantine territory they captured during their advance. In this way Alexios gained territory in the north and west of Asia Minor.

During the twelfth century Byzantine armies continued to advance, reconquering much of the lost territory in Asia Minor. The recovered provinces included the fertile coastal regions, along with many of the most important cities. By 1180 C.E., the Empire had gone a long way to reversing the damage caused by the Battle of Manzikert. Under Manuel Komnenos, the emperor had attained the right to appoint the King of Hungary, and Antioch had become a vassal of the empire. The crusader states' rulers were also technically vassals of the Emperor.

With the restoration of firm central government, the empire became fabulously wealthy. The population was rising (estimates for Constantinople in the twelfth century vary from approximately 400,000 to one million); towns and cities across the empire flourished. Meanwhile, the volume of money in circulation dramatically increased. This was reflected in Constantinople by the construction of the Blachernai palace, the creation of brilliant new works of art, and the general prosperity of the city at this time.

It is possible that an increase in trade, made possible by the growth of the Italian city-states, may have helped the growth of the economy at this time. Certainly, the Venetians and others were active traders in Constantinople, making a living out of shipping goods between the Crusader Kingdoms of Outremer (literally 'overseas,' the term used in Europe for their Crusader outposts) and the West while also trading extensively with Byzantium and Egypt. The Venetians had factories on the north side of the Golden Horn, and large numbers of westerners were present in the city throughout the twelfth century.

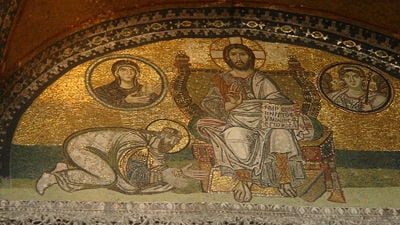

In artistic terms, the twelfth century was a very productive period in Byzantium. There was a revival in mosaic art, for example. Mosaics became more realistic and vivid, with an increased emphasis on depicting three-dimensional forms. There was an increased demand for art, with more people having access to the necessary wealth to commission and pay for such work. From the tenth to the twelfth centuries, European religious art was hugely indebted to Constantinople. What emerged as the Romanesque style was derived from the Byzantines.

The Palaiologoi, 1204-1453

However, after the demise of the Komnenian dynasty at the close of the twelfth century, the Byzantine Empire declined steeply. The disastrous misrule of the Angelid dynasty (1185-1204) resulted in the collapse of the empire and the disastrous capture and sack of Constantinople by soldiers of the Fourth Crusade on April 13, 1204. For the subsequent half-century or more, Constantinople remained the focal point of the Roman Catholic Latin Empire, set up after the city's capture under Baldwin IX. During this time, the Byzantine emperors made their capital at nearby Nicaea, which acted as the capital of the temporary, short-lived Empire of Nicaea and a refuge for refugees from the sacked city of Constantinople. From this base, Constantinople was eventually recaptured from its last Latin ruler, Baldwin II, by Byzantine forces under Michael VIII Palaeologus in 1261.

After the reconquest by the Palaeologi, the imperial palace of Blachernae in the northwest of the city became the main imperial residence, the old Great Palace upon the shores of the Bosporus going into decline. Finally, the city fell to Sultan Mehmed II on May 29, 1453. He allowed the troops to loot the city for three days. Many residents were sold into slavery. Mehmet protected certain buildings, either planning to use them himself of to house the Orthodox Patriachate which he would need to control the population.

European Response to the Fall of Constantinople

As soon as word reached Rome, Pope Calixtus III started to campaign for a crusade to liberate the city. This continued under his successor, Pope Pius II. In 1457 a crusader army led by St. John of Capistrano confronted a small Turkish force at Belgrade and routed them. This prevented Ottoman expansion for a short period. The following year, "a papal fleet of sixteen galleries captured more than twenty-five Turkish ships" (Riley-Smith, 277). Efforts to raise a larger army continued but the European powers could not "sink their differences" to collaborate effectively. Several naval raids were made on Turkish ports and Pius II himself died of the plague while attempting to lead a crusade.

Mehmet II responded (1480 C.E.) by seizing Rhodes and with a land invasion in Italy which almost caused the new Pope to flee from Rome. By the middle of the sixteenth century, however, most of the Balkans lay in Muslim hands, becoming a buffer-zone between Western Europe and what was regarded as the Ottoman threat.

Importance

There are a number of dimensions to the historical significance of Constantinople.

Culture

Constantinople was one of the largest and richest urban centers in the Eastern Mediterranean during the late Roman Empire, mostly due to its strategic position commanding the trade routes between the Aegean Sea and the Black Sea. After the fourth century, when Emperor Constantine I relocated his eastern capital to Byzantium, it would remain the capital of the eastern, Greek-speaking empire, bar several short interregnums, for over a thousand years. As the capital of the Byzantine Empire, the Greeks called Constantinople simply "the City," while throughout Europe it was known as the "Queen of Cities."

In its heyday, roughly corresponding to the Middle Ages, it was the richest and largest European city, exerting a powerful cultural pull and dominating economic life in the Mediterranean. Visitors and merchants were especially struck by the beautiful monasteries and churches of the city, particularly the Hagia Sophia, or the Church of Holy Wisdom. A fourteenth-century Russian traveler, Stephen of Novgorod, wrote, "As for St Sofia, the human mind can neither tell it nor make description of it."

The cumulative influence of the city on the west, over the many centuries of its existence, is incalculable. In terms of technology, art and culture, as well as sheer size, Constantinople was without parallel anywhere in Europe for a thousand years.

Politics

The city provided a defense for the eastern provinces of the old Roman Empire against the barbarian invasions of the fifth century. The 60-foot-tall walls built by Theodosius II (413-414 C.E.) were essentially invincible to the barbarians who, coming from the Lower Danube, found easier targets to the west rather than pursing the richer provinces to the east in Asia beyond Constantinople. This allowed the east to develop relatively unmolested, while Rome and the west collapsed.

Architecture

The influence of Byzantine architecture and art can be seen in its extensive copying throughout Europe, particular examples include St. Mark's in Venice, the basilica of Ravenna and many churches throughout the Slavic East. Also, alone in Europe until the thirteenth-century Italian florin, the Empire continued to produce sound gold coinage, the solidus of Diocletian becoming the bezant prized throughout the Middle Ages. Its city walls (the Theodosian Walls) were much imitated (for example, see Caernarfon Castle) and its urban infrastructure was moreover a marvel throughout the Middle Ages, keeping alive the skill and technical expertise of the Roman Empire.

Religious

Constantine ensured that the "Bishop of Constantinople," who eventually came to be known as the patriarch of Constantinople, was elevated to about the same pre-eminent rank of honor as the bishop of Rome, the pope of Old Rome, who however retained a certain primacy of jurisdiction and was still named officially first patriarch.[2] They were "first among equals" in honor, a situation which would eventually lead to a East-West schism that divided Christianity into Western Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy. The patriarch of Constantinople is still today considered first among equals in the Orthodox Church along with the patriarchs of Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem, Moscow, and the later Slavic Patriarchs. This position is largely ceremonial but still today carries emotional weight.

Notes

- ↑ Scriptores originum Constantinopolitanarum. Edited by T. Preger (see A. A. Vasiliev (1952), History of the Byzantine Empire Vol. I. p. 188).

- ↑ The Seven Ecumenical Councils: The Fourth Canon of the First Council of Constantinople. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved April 24, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Crowley, Roger. Constantinople: The Last Great Siege, 1453. London: Faber and Faber, 2005. ISBN 0571221858

- Freely,John, and Ahmet S. Cakmak. Byzantine Monuments of Istanbul. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. ISBN 0521772575

- Harris, Jonathan. Byzantium and the Crusades. New York, NY: Hambledon Continuum, 2003. ISBN 1852855010

- Mansel, Philip. Constantinople: City of the World's Desire, 1453-1924. New York, NY: St. Martin's Griffin, 1998. ISBN 0312187084

- Norwich, John Julius. Byzantium: The Early Centuries. New York, NY: A. A. Knopf, 1989. ISBN 0394537785

- Norwich, John Julius. Byzantium: The Apogee. New York, NY: A. A. Knopf, 1992. ISBN 0394537793

- Norwich, John Julius. Byzantium: The Decline and Fall. New York, NY: A. A. Knopf 1995. ISBN 0679416501

- Phillips, Philips. The Fourth Crusade and the Sack of Constantinople. Pimlico, 2005. ISBN 1844130800

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan. The Crusades. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005. ISBN 0300101287

- Runciman, Steven. The Fall of Constantinople, 1453. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN 0521398320

External Links

All links retrieved March 20, 2017.

- Mosaics of Hagia Sophia - The Deesis Mosaic from Hagia Sophia

- Constantinoupolis on the web Select internet resources on the history and culture of Constantinople

- Istanbul was Constantinople? – Foundation for the Advancement of Sephardic Studies and Culture

- Constantinople, from History of the Later Roman Empire, by J. B. Bury (1923)

- History of Constantinople from The Catholic Encyclopedia

- Byzantium 1200 – A project aimed at creating computer reconstructions of the Byzantine Monuments located in Istanbul, Turkey as of year 1200

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.