Second Council of Nicaea

| Second Council of Nicaea | |

|---|---|

| Date | 787 |

| Accepted by | Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Lutheranism |

| Previous council | (Catholic) Third Council of Constantinople (Orthodox) Quinisext Council |

| Next council | (Catholic) Fourth Council of Constantinople (Orthodox) Fourth Council of Constantinople |

| Convoked by | Constantine VI and Empress Irene (as regent) |

| Presided by | Patriarch Tarasios of Constantinople, legates of Pope Adrian I |

| Attendance | 350 (two papal legates) |

| Topics of discussion | Iconoclasm |

| Documents and statements | veneration of icons approved |

| Chronological list of Ecumenical councils | |

The Second Council of Nicaea, also known as the the Seventh Ecumenical Council, was a meeting of Christian bishops in 787 C.E. in Nicaea, present-day İznik, Turkey. The council acted to restore the veneration of icons, a practice which had been suppressed by in the Byzantine Empire during the reign of Leo III (717-741) and officially banned by his son, Constantine V (741-775). It overturned the earlier Council of Hieria, also known as the Iconoclast Council, which had earlier described itself as the "Seventh Ecumenical Council."

Iconoclasm developed in the context of the Muslim advance as Christians began to question whether the use of icons violated the Ten Commandments and emperors felt that their military setbacks against the Muslims were the result of God's displeasure. After the death of Emperor Leo IV Isaurian, his wife, Empress Irene, moved to restore icon veneration by appointing her former secretary as the new patriarch of Constantinople and summoning a new ecumenical council. The council was initially convened in the capital but was interrupted due to a violent outbreak of opposition. It was then moved to Nicaea, where it was concluded after eight sessions. It declared the propriety of "images of Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, the holy angels, as well as those of the saints, and other pious and holy men." It also deposed all bishops and clergy who refused to allow such things.

The council was later overturned by by Emperor Leo V, who instituted a second period of iconoclasm in 813. This would last until another empress, Theodora, came to power as regent in 843 and restored the use of images based on II Nicaea. The council is particularly important in Eastern Orthodoxy and is the last council to be recognized as ecumenical by both Catholic and Orthodox traditions.

Background

In Byzantine Christian history, iconoclasm developed in part as a reaction to Islam. The military threat from the expanding Muslim empire, coupled with its expanding cultural influence, created substantial opposition to the use of icons among certain factions in the Eastern Roman Empire. Some took the view that ions were offensive to God, a violation of one of the Ten Commandments: "You shall not make for yourself an idol in the form of anything in heaven above or on the earth beneath or in the waters below" (Ex. 20:4). Others argued that icons strengthened the Muslims in their claims that Islam was more pure than Christianity in its adherence to God's laws.

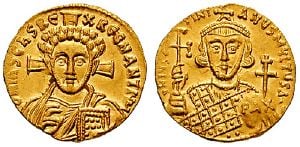

After Emperor Justinian II issued gold coins featuring a full-face image of Christ in 695, the accusation that these constituted "graven images" caused Patriarch Germanus I of Constantinople to write that "now whole towns and multitudes of people are in considerable agitation over this matter." Between 726 and 730 the Emperor Leo III Isaurian ordered the removal of an image of Jesus over the imperial palace gate in Constantinople, possibly believing that recent military setbacks against the Muslims was due to God's anger against Christian idolatry. Although the move was met with violent opposition, Leo forbade the veneration of icons in an edict 730, confiscating not only icons and statues, but also many other valuable decorated objects from the churches. Patriarch Germanus opposed the ban and either resigned or was deposed. In the West, Pope Gregory III condemned the emperor's actions, resulting in a new schism between Rome and Constantinople.

Leo's iconoclastic policy was strengthened during the reign of his son Constantine V (741-775). In 754, Constantine V summoned the "first" Seventh Ecumenical Council, also known as the "Iconoclast Council," in which 338 bishops participated and condemned the veneration of icons as heresy, declaring: "If anyone ventures to represent the divine image of the Word (Christ) after the Incarnation with material colors, let him be anathema! …If anyone shall endeavor to represent the forms of the saints in lifeless pictures… let him be anathema!"

Some monasteries, however, became strongholds of icon veneration. The Syrian monk John of Damascus emerged as the main opponent of iconoclasm, together with Theodore the Studite. Constantine V moved forcefully against those monasteries which did not comply with his iconclastic policy. His son, Leo IV (775-80), initially attempted to reconcile the pro- and anti-icon factions, but near the end of his life, took a more severe attitude in support of iconoclasm.

Leo IV's wife, Empress Irene, however, supported icon veneration. After Leo's death, she took power as regent for her son, Constantine VI (780-97). It was she who initiated a new ecumenical council, ultimately called the Second Council of Nicaea

The council

The council initially met in the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople. However, soldiers in sympathy with the iconoclast cause entered the church and broke up the assembly. Irene's government, under the pretext of a military campaign, ordered the iconoclastic guard to be sent away from the capital, where it was then disarmed and disbanded.

The council was again summoned to meet, this time in Nicaea, since Constantinople was still thought to harbor too many iconoclasts for the council to be conducted in safety. It assembled on September 24, 787 with about 350 bishops present. In the end, 308 bishops or their representatives signed its acts. Patriarch Tarasios of Constantinople, who had formerly been Irene's imperial secretary and had earlier renounced iconoclasm, presided.

The bishops argued that the veneration of icons was lawful based on Exodus 25:17ff (in which God commands the creation of golden cherubim) and other biblical passages, and especially from a series of passages of the Church Fathers whose orthodox authority was beyond question. It was determined that:

As the sacred and life-giving cross is everywhere set up as a symbol, so also should the images of Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, the holy angels, as well as those of the saints and other pious and holy men be embodied in the manufacture of sacred vessels, tapestries, vestments, etc., and exhibited on the walls of churches, in the homes, and in all conspicuous places, by the roadside and everywhere, to be revered by all who might see them. For the more they are contemplated, the more they move to fervent memory of their prototypes. Therefore, it is proper to accord to them a fervent and reverent adoration, not, however, the veritable worship which, according to our faith, belongs to the Divine Being alone — for the honor accorded to the image passes over to its prototype, and whoever adores the image adores in it the reality of what is there represented.

The clear distinction between the adoration offered to God, and that accorded to the images may well be looked upon as a result of the iconoclastic reform. Moreover, sculpture in the round was condemned as "sensual," an attitude that would have profound implications on Christian art for centuries to come. The council also passed 22 canons dealing with various aspects of ecclesiastical reform. Among them may be mentioned:

- Canon 3 condemns the appointment of bishops, priests, and deacons by secular princes.

- Canon 7 commands that relics are to be placed in all churches: No church is to be consecrated without relics.

- Canon 8 prescribes precautions to be taken against feigned converts from Judaism.

- Canon 9 decrees that iconoclastic writings must be surrendered.

- Canon 16 insists that clergy must not wear luxurious apparel.

- Canon 18 commands that women are not to dwell in bishops' houses or in monasteries.

- Canon 20 prohibits double monasteries (for both men and women).

Aftermath and legacy

Iconoclasm, however, was not dead yet. Emperor Leo V (reigned 813–820), after a series of military failures which he, too, saw as indicative of divine displeasure, instituted a second period of iconoclasm in 813. He was succeeded by Michael II, who confirmed the decrees of the Iconoclast Council of 754. As with the earlier iconoclastic age, this period would be brought to an end by the piety of a reigning queen. When Michael's son Theophilus died, his wife Theodora became regent for their minor heir, Michael III. Like Irene 50 years before, proclaimed the restoration of icons, with the support of the iconodule monks in 843.

This Second Council of Nicaea, together with Theodora's act of restoration, is celebrated in the Eastern Orthodox Church as "The Sunday of the Triumph of Orthodoxy" each year on the first Sunday of Great Lent—the fast that leads up to Easter—and again on the Sunday closest to October 11 (the Sunday on or after October 8). The council is the last ecumenical council accepted as such by both the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alberigo, Giuseppe. The Oecumenical Councils from Nicaea I to Nicaea II (325-787). (Conciliorum oecumenicorum generaliumque decreta, 1.) Turnhout: Brepols, 2006. ISBN 9782503523637.

- Davis, Leo Donald. The First Seven Ecumenical Councils (325-787): Their History and Theology. Theology and life series, v. 21. Collegeville, Minn: Liturgical Press, 1990. ISBN 9780814656167.

- Martin, Edward James. A History of the Iconoclastic Controversy. New York: AMS Press, 1978. ISBN 9780404161170.

- Ostrogorsky, George. History of the Byzantine State. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1969. ISBN 0813505992.

- Pelikan, Jaroslav. Imago Dei: The Byzantine Apologia for Icons. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990. ISBN 9780691099705.

This article includes content derived from the 1907 Catholic Encyclopedia and the 1914 Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, both now in the public domain.

| ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.