| Part of the series on History of Islam |

| Beliefs and practices |

|

Oneness of God |

| Major figures |

|

Muhammad |

| Texts & law |

|

Qur'an · Hadith · Sharia |

| Branches of Islam |

| Sociopolitical aspects |

|

Art · Architecture |

| See also |

|

Vocabulary of Islam |

Islam (Arabic: الإسلام al-islām) "obedience (or submission) to God" is a monotheistic faith, one of the Abrahamic religions, and the world's second largest religion. Many Muslims dislike the term religion, since to them it implies a private faith whereas the ideal for most Muslims is a community in which the religious, social, and political are united.

Muhammad, the prophet of Islam, governed the first Muslim ummah (nation or community), his model being a single, trans-cultural, trans-racial community. Some Muslims fail to see this ideal expressed in Western views of the nation state, and thus see the latter as an alien to their view of human social organization. By some counts, Islam serves as the tradition for more than a billion men and women. It represents for believers God's ideal, a life of harmony and balance between spiritual and material concerns, between pleasure and worship, work and prayer.

Islam has a strict moral code that also encourages generosity and concern for the disadvantaged (the mustad'afun, or oppressed) and the development of a sense of God-consciousness (taqwa) that pervades the whole of life. The world is regarded as a sacred trust (amana) from God for which humanity will be required to render an account. The world should, therefore, be properly cared for, not exploited.

Assessments of Muhammad vary. Secular historians who explain Islam's origin and success in terms of functionalist theory, saying that it provides societies with a moral framework and shared beliefs, may believe that Islam—like religions in general—was Muhammad’s invention. Those who believe that God works through history and who attribute value to all the world's religions are likely to see Muhammad and Islam as instruments of divine providence. Not all of those who believe in providential history have understood Islam positively, but many people view it as a source of moral guidance and of spiritual value in the world, elevating obedience to God above self-interest, party, group, racial, or national interest. For example, Islam teaches that the whole of society sins when any members starve, that an employer should treat employees as they wish to be treated themselves, that individual ownership of property or wealth are not absolute rights but subject to the public weal, and that anonymous generosity (infaq) is one of the highest virtues (Qur’an 13:22).

Etymology

In Arabic, Islām from the root 'slm' (silm), means to be in peaceful submission, to surrender, to obey [God] which is to be in a state of peace. Islam's literal meaning is thus, "The active willful surrender, submission, obedience, in purity to the will of another (Allah) in complete peace." Islam, understood as voluntary submission to God, is described as a Din or Deen, meaning "way of life" and/or "religion" (also Day). Etymologically, Islam is derived from the same root as, for example, Salām meaning "peace" (also a common salutation). The word Muslim is also related to the word Islām and means one who "surrenders" or "submits" to God.

Beliefs

Followers of Islam, known as Muslims, believe that God (or, in Arabic, Allah, a masculine noun) revealed his direct word for mankind to Muhammad (c. 570 – 632) and other prophets, including Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, and Jesus, as dictated by the Angel Gabriel. Muhammad, who is considered by Muslims as the last Prophet (and after whose name, and that of all prophets, Muslims say, "peace be upon him") received the first revelation of a chapter of the Qur'an in 610 C.E. and the last just before he died in 632 C.E. Muslims assert that the Qur'an revealed to Muhammad is the main written record of revelation to humankind, which they believe to be flawless, immutable, and the final revelation of God. Muslims believe that parts of the Gospels, Torah, and Jewish prophetic books have been forgotten, misinterpreted, or distorted by their followers, although there is discussion as to whether distortion is textual or interpretive. Most Muslims, however, view the Qur'an as corrective of Jewish and Christian scriptures. Non-Muslims tend to regard Muhammad as the author of the Qur'an and interpret Islam's origin as a response to the circumstances and needs of the day. They thus examine the social, economic, and religious context of sixth century Arabia in order to understand the conditions and influences that gave birth to Muhammad's religion, one that built on the two earlier Abrahamic faiths. Muslims reject the idea that Islam's origin owes itself to anything other than God's mercy in revealing God's will to a forgetful and disobedient humanity.

Muslims hold that Islam is essentially the same belief as that of all the messengers sent by God to mankind since Adam, with the Qur'an the definitive scripture or revelation of the Muslim faith codifying the final revelation of God. Essentially, all prophets received the same message of obedience to God. Muslims believe that there have been 124,000 prophets including one to each human community (Qur’an 10:48). Islamic teaching sees Judaism and Christianity as derivations of the teachings of certain of these prophets—notably Abraham—and therefore acknowledges their Abrahamic roots, while the Qur'an calls them "People of the Book." Islam has two primary branches of belief, based largely on a historical disagreement over the succession of authority after Muhammad's death; these are known as Sunni and Shi'a (the words Sunni and Shi'a do not appear anywhere in Qu'ran). There are various sub-divisions of both main branches and historically other branches existed, which are no longer extant. There is also the popular devotional or mystical tradition known as tasawuf, or Sufism, which exists in both branches and has historically helped to bridge the divide between them.

The basis of Islamic belief is found in the shahadah ("two testimonies"): lā ilāhā illā-llāhu; muhammadur-rasūlu-llāhi —"There is no god but God; Muhammad is the messenger of God" (Shi'a add, "and Ali is the heir of God"). In order to become a Muslim, this confession needs to be recited before witnesses as a verbal or outer declaration of inner faith (iman). This is known as iman, or faith, and represents the foundation or first pillar of Islam, of which there are five (Arkan-al-Islam). These are not listed in the Qur'an but in the second most authoritative source for Muslim faith, the hadith (accounts of Muhammad's sunnah, or example, that is, his words and deeds). Muslims believe that Muhammad's own life exemplified the Qur'an's teaching, that he was inspired and lived a life in full and complete harmony with God. Taqwa (God-consciousness) dominated everything he said and did. The Qur'an commanded the first Muslims to obey God and God's prophet (Qur’an 4:59).

Six articles of belief

There are six basic beliefs shared by all Muslims:

- Belief (Iman) in God, the one and only one worthy of all worship.

- Belief in all the Prophets (nabi) and Messengers (rasul) (sent by God). Messengers all received a fresh revelation in the form of a scripture (Kitab, or book) from God. Prophets remind people of God's message.

- Belief in the Books (kutub, plural of Kitab) sent by God. These include all the scriptures given to the prophets.

- Belief in the Angels (malaikah).

- Belief in the Day of Judgment (qiyamah) and in the Resurrection.

- Belief in Destiny (Fate) (qadar). (Note that this does not mean one is predetermined to act or live a certain life. God has given the free will to do and make decisions.)

The Qur'an itself does not contain a creedal statement but by the end of the eighth century several had been formulated, following theological debate. Typically, a creed (aqidah) affirms the following (in English):

- "I believe in God; and in His Angels; and in His Scriptures; and in His Messengers; and in The Final Day; and in Fate, that Good and Evil are from God, and Resurrection after death be Truth.

- "I testify that there is nothing worthy of worship but God; and I testify that Muhammad is His Messenger."

God

The fundamental concept in Islam is the oneness of God (tawhid). This monotheism is absolute, not relative or pluralistic in any sense of the word. God is described in Sura al-Ikhlas, (chapter 112) as follows: Say "He is God, the one, the Self-Sufficient master. He never begot, nor was begotten. There is none comparable to Him."[1]

In Arabic, God is called Allāh. The word is etymologically connected to ʾilah (deity), ultimately from Proto-Semitic *ʾilâh-, and indirectly related to Hebrew El (god). Allāh is also the word used by Christian and Jewish Arabs, translating ho theos of the New Testament and of the Septuagint (Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible); it predates Muhammad and in its origin does not specify a "God" different from the one worshiped by Judaism and Christianity, the monotheistic religions to which Muhammad's teaching stood in contrast. Some Christians and Orthodox Jews dispute the notion that the God that Muslims worship is the same God described in the Old and New Testaments, but the Qur'an itself is emphatic on this issue; "And say: 'We believe in what was revealed to us and in what was revealed to you, and our God and your God is one and the same; to Him we are submitters.'"(Qur’an 29:46). Christian belief in Trinity (One God in three persons) and in Jesus as God's son, however, are condemned in the Qur'an (4:171) as they associate partners with God (shirk, a heresy). The implicit usage of the definite article in Allāh linguistically indicates the divine unity. Sura An-Nisa 171 proclaims:

O People of the Scripture! Do not exaggerate in your religion nor utter aught concerning Allah save the truth. The Messiah, Jesus son of Mary, was only a messenger of Allah, and His word which He conveyed unto Mary, and a spirit from Him. So believe in Allah and His messengers, and say not "three." Cease! (it is) better for you! Allah is only One God. Far is it removed from His transcendent majesty that he should have a son. His is all that is in the heavens and all that is in the earth. And Allah is sufficient as its defender.

No Muslim visual images or depictions of God exist because such artistic depictions may lead to idolatry and are thus prohibited. A similar position in Christian theology is termed iconoclasm. Moreover, most Muslims believe that God is incorporeal, rendering any two- or three-dimensional depictions impossible. Instead, Muslims describe God by the many 99 Names or divine attributes mentioned in the Qur'an. All but one sura (chapter) of the Qur'an begins with the phrase "In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful." These are consequently the most important divine attributes in the sense that Muslims repeat them most frequently during their ritual prayers (called salah in Arabic, and in India, Pakistan, and Turkey called namaaz (a Persian word). Salah is Islam's second pillar. However, passages in the Qur'an that describe God using anthropomorphic language, such as God seeing, hearing, or sitting on a throne (or that His face will be seen on the Day of Judgment) resulted in debate about whether God possesses “human” characteristics. The dominant view that emerged was that such descriptions should be accepted “without asking how” (bila kayfa). God does see and hear in a manner that resembles but is not identical to human seeing or hearing.

The tenets of Islam

There are two main schools in Islam: the Sunni and the Shi'a. Sunni Muslims make up roughly 90 percent of the Muslim world. Sunni Islam's most fundamental tenets are referred to as the Five Pillars of Islam, while Shi’a Islam has a slightly different terminology, encompassing five core beliefs (the "roots of religion") and ten core practices (the "branches of religion").[2] All Muslims agree on the following statements, which Sunnis term the Five Pillars of Islam, and Shi’a would consider two of the Roots of Religion and four of the Branches of Religion:

- Shahadah: The Testimony that there is none worthy of worship except God and that Muhammad is His messenger.

- Salah: Establishing of the five daily Prayers (salah).

- Zakat: The Giving of Zakaah (charity), which is one fortieth (2.5 percent) of the net worth of savings kept for more than a year, with few exemptions, for every Muslim whose wealth exceeds the nisab (the amount of money needed to sustain an average family for one year), and 10 or 20 percent of the produce from agriculture. This money or produce is distributed among the Muslim poor.

- Ramadhan: Fasting from dawn to dusk in the month of Ramadan (sawm).

- Hajj: The Pilgrimage (Hajj) at Mecca during the month of Dhul Hijjah, which is compulsory once in a lifetime for one who has the ability to do it. Often, this is referred to as the pilgrimage to Mecca but technically it is the pilgrimage at Mecca, since it begins and ends in Mecca and even someone who lives in Mecca can perform the pilgrimage without traveling very far.

The Shi’a include the following, though some of these beliefs are also considered accurate in Sunni Islam as well:

- The Justice of God ('Adl)

- The Resurrection (Me'ad)

And four of what the Shi’a call the Branches of Religion:

- Enjoining what is good (Amr-bil-Ma'roof)

- Forbidding what is evil (Nahi-anil-Munkar)

- Striving to seek God's approval (Jihad)

- Paying the tax on profit (Khums)

While two "branches," and one "root," are specifically Shi’a:

- The belief in the divinely appointed and guided imamate of Ali ibn Abi Talib and some of his descendants (Imamah)

- To love the Ahl-ul-Bayt (Household of the Prophet) and their followers (Tawalla)

- To hate the enemies of the Ahl-ul-Bayt (Tabarra)

The original schism between the two groups occurred after Muhammad's death when the majority decided that inspired leadership had finished and that any pious Muslim might be selected as titular leader and deputy, or Caliph, while the whole community would corporately act as guardian of the tradition (sunnah) of the prophet. The Shi'a rejected this, contending that Muhammad had nominated Ali as his successor and that only a male descendent of Muhammad should govern, since they inherit special inspiration and status.

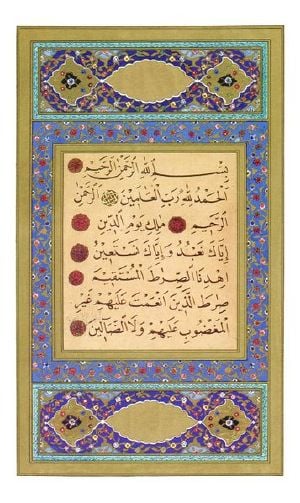

The Qur'an

The Qur'an is the sacred book of Islam. It has also been called, in English, the Koran and the Quran. Qur'an is the currently preferred English transliteration of the Arabic original (قرآن); it means “recitation.” Although it is referred to as a "book," when a Muslim refers to the Qur'an, they are referring to the actual text, the words, rather than the printed work itself. (Some Muslims dislike calling the Qur'an a text as this implies that it has something in common with works or texts penned by men and women.)

Muslims believe that the Qur'an was revealed to the Prophet Muhammad by the archangel Gabriel on numerous occasions between the years 610 and Muhammad's death in 632 (sometimes the words of the Qur'an seemed to be burnt or descended into Muhammad's heart and accounts do not refer to the angel, but many do). In addition to memorizing his revelations, his followers are said to have written them down on parchments, stones, and other media, so that the entire Qur'an was written down during the lifetime of Prophet Muhammad. There are 114 suras (chapters) and about 6,286 ayahs, or verses (depending on the exact division, which varies).

Muslims believe that the Qur'an available today is the same as that revealed to Prophet Muhammad and by him to his followers, who memorized his words. Scholars accept that the version of the Qur'an used today was first compiled in writing by the third Caliph, Uthman, sometime between 650 and 656. He sent copies of his version to the various provinces of the new Muslim empire, and directed that all variant copies be destroyed. However, some skeptics doubt the recorded oral traditions (hadith) on which the account is based and will say only that the Qur'an must have been compiled before 750.

There are also numerous traditions, and many conflicting academic theories, as to the provenance of the verses later assembled into the Qur'an (this is covered in greater detail in the article on the Qur'an). Most Muslims accept the account recorded in several hadith, which state that Abu Bakr, the first caliph, ordered Zayd ibn Thabit to collect and record all the authentic verses of the Qur'an, as preserved in written form or oral tradition. Zayd's written collection, privately treasured by Muhammad's widow Hafsa bint Umar, was used by Uthman and is the basis of today's Qur'an.

Uthman's version organized the revelations, or suras, roughly in order of length, with the longest suras at the start of the Qur'an and the shortest ones at the end. More conservative views state that the order of most suras was divinely set. Later scholars have struggled to put the suras in chronological order, and among Muslim commentators, at least there is a rough consensus as to which suras were revealed in Mecca and which at Medina. Some suras (e.g., surat Iqra) were revealed in parts at separate times.

Because the Qur'an was first written (date uncertain) in the Hijazi, Mashq, Ma'il, and Kufic scripts, which write consonants only and do not supply the vowels, and because there were differing oral traditions of recitation, as non-native Arabic speakers converted to Islam, there was some disagreement as to the exact reading of many verses. Eventually, scripts were developed that used diacritical markings (known as points) to indicate vowels. For hundreds of years after Uthman's critical revision, Muslim scholars argued as to the correct pointing and reading of Uthman's unpointed official text (the rasm). Eventually, most commentators accepted seven variant readings (qira'at) of the Qur'an as canonical, while agreeing that the differences are minor and do not effect the meaning of the text.

The form of the Qur'an most used today is the Al-Azhar text of 1923, prepared by a committee at the prestigious Cairo university of Al-Azhar.

The Qur'an early became a focus of Muslim devotion and eventually a subject of theological controversy. In the eighth century, the Mu'tazilis claimed that the Qur'an was created in time and was not eternal. Their opponents, of various schools, claimed that the Qur'an was eternal and perfect, existing in heaven before it was revealed to Muhammad. The Asharite theology (which ultimately became predominant) held that the Qur'an was uncreated. However, modern liberal movements within Islam are apt to take something approaching the Mu'tazili position.

Most Muslims regard paper copies of the Qur'an with extreme veneration, wrapping them in a clean cloth, keeping them on a high shelf, and washing as for prayers before reading the Qur'an. Old Qur'ans are not destroyed as wastepaper, but burned or deposited in Qur'an graveyards.

Almost every Muslim has memorized some portion of the Qur'an in the original language. Those who have memorized the entire Qur'an are known as hafiz. This is not a rare achievement; it is believed that there are millions of hafiz alive today.

From the beginning of the faith, most Muslims believed that the Qur'an was perfect only as revealed in Arabic. Translations were the result of human effort and human fallibility, as well as lacking the inspired poetry believers find in the Qur'an. Translations are therefore only commentaries on the Qur'an, or "translations of its meaning," not the Qur'an itself. Many modern, printed versions of the Qur'an feature the Arabic text on one page, and a vernacular translation on the facing page. The Qur'an is both an oral and an aural text, that is intended to be spoken and heard rather than read; and the qurra' (reciters, plural of qari), whose task is to make a beautiful recitation (tajwid, correct recitation), attract large audiences throughout the Muslim world. Indeed, recitation can be considered a form of art. The art of calligraphy, rendering the Qur'an beautiful in written form, is also an advanced art in the Muslim world.

Prophets

The Qur'an speaks of God appointing two classes of human servants: messengers (rasul in Arabic), and prophets (nabi in Arabic and Hebrew). In general, messengers are the more elevated rank, but Muslims consider all prophets and messengers equal. All prophets are said to have spoken with divine authority; but only those who have been given a major revelation or message are called messenger.

Notable messengers include Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses (Musa), Jesus (Isa), and Muhammad, all belonging to a succession of men guided by God. Islam demands that a believer accept most of the Judeo-Christian prophets, making no distinction between them. In the Qur'an, 25 specific prophets are mentioned. Muhammad's example, though, takes priority because he received God's last testament and had a universal, not a localized mission (Qur’an 7: 158)

Mainstream Muslims regard Muhammad as the “Last Messenger” or the “Seal of the Prophets” (Qur’an 33: 40) based on the canon. However, there have been a number of sects whose leaders have proclaimed themselves the successors of Muhammad, perfecting and extending Islam, or, whose devotees have made such claims for their leaders. However, most Muslims remain unaffected by those claims and simply regard those said groups to be deviant from Islam.

Islamic eschatology

Islamic eschatology is concerned with the Qiyamah (end of the world) and the final judgment of humanity. Like Christianity and some sects of modern Judaism, Islam teaches the bodily resurrection of the dead, the fulfillment of a divine plan for creation, and the immortality of the human soul; the righteous are rewarded with the pleasures of Jannah (Paradise), while the unrighteous are punished in Jahannam (a fiery Hell, from the Hebrew ge-hinnom or "valley of Hinnom"; usually rendered in English as Gehenna). A significant fraction of the Qur'an deals with these beliefs, with many hadiths elaborating on the themes and details. Muslim descriptions of Paradise (the promise of virgins in heaven, for example; see Qur’an 55: 60f) have been much ridiculed and censored by non-Muslims but such criticism often fails to appreciate the allegorical nature of these passages. Popular end time traditions give Jesus a special role in helping to defeat ad-Dajjal, the last enemy of righteousness. He will then break the cross and judge humanity not by the Gospel but by the Qur'an. Many Muslims believe that before this, Jesus will first marry and have children. Some think that he will then die (having not died on the Cross), since in the Qur'an he was taken straight up into heaven without dying (Qur’an 4:171). Qur’an 4:159 states, “and he will be a witness against them on the day of resurrection” implies a judgmental role for Jesus. This is understood to refer to his witness against Christians. The figure of al-Mahdi (the twelfth Shi'a Imam) is also eschatological. When he returns, the kingdom of justice and peace will be established. Historically, several people have been called the Mahdi and some claimed the title for themselves {see the article on the Mahdi of Sudan, Muhammad Ahmad). Many Sunnis also cite a tradition attributed to Muhammad that before the Day of Judgment, a member of his own house will appear, end tyranny and injustice, and establish universal peace. This figure is associated with the Madhi, who will be born in Mecca (as was Muhammad) and whose father will have the same name as Muhammad's, that is, Abdullah. Tradition has it that both Jesus and the Mahdi will live out their natural lives on earth, once ad-Dajjal has been defeated. All people will then embrace Islam. The tradition is not found in the most authoritative collection, but it is considered sound.

Other beliefs

Other beliefs include the existence of Angels, the Jinns (a species of beings not composed of solid matter, but fire), and the existence of magic (the practice of which is strictly forbidden).

Religious and political authority

Religious Leadership

Sunnis and Shi'a approach the issue of religious authority differently. For Sunnis, there is no official authority who decides whether a person is accepted into, or dismissed from, the community of believers, known as the ummah ("family" or "nation") or what is or is not the right or only Muslim view. Sunnis believe that all Muslims have the corporate responsibility of preserving and interpreting the tradition and valie ijma (consensus) based on a saying of Muhammad that his “community would not agree in error.” The principle of shura (consultation) (Qur’an 42:38; 3:159) is also important, thus politically as well as spiritually no single individual can claim unique authority.

Islam is open to all, regardless of race, age, gender, or previous beliefs. It is enough to believe in the central beliefs of Islam. This is formally done by reciting the shahada, the statement of belief of Islam, without which a person cannot be classed a Muslim. It is enough to believe and say that one is a Muslim, and behave in a manner befitting a Muslim to be accepted into the community of Islam. In practice, though, ijma and shura have often been limited in scope to those who know, or who are considered to be the “best” (see Qur’an 6:165; 4:58), which means that an elite class has often imposed its version of Islam on others, demanding obedience. Mernissi comments that the obligation to obey “the leader” has dominated Islamic discourse. “Allegiance to the leaders” became synonymous with “faithfulness to God,” inseparably “linking three words: din (religion), i'tiqad (belief) and ta'a (obedience) so that ra'y (personal opinion), ihdath (innovation), and ibda (creation)” are “condemned as negative, subversive.”[3]

Shi'a Islam recognizes the unique authority of the Imam, the designated male heir of the prophet. The majority of Shi'a believe that the Imam is now “hidden,” in the absence on earth of the Imam, the senior scholars (mujtahidun) exercise special authority and all Shi'a submit (taqlig, imitate) to the authority of a mujtahid. Mernissi argues that it was more often than not a male elite that imposed his version of Islam on everyone else and that, unlike the originally egalitarian message of Muhammad's Islam, this version favored men's interests above women's.[3]

Political Leadership

Many Muslims believe that all aspects of life should be regulated by the ideals of Islam within what is often called an “Islamic state.” This expression itself is not found in the early sources but for many the ummah under Muhammad in Medina, and under the first four rightly guided caliphs, was an Islamic state in that the law of the land was the sharia and a person of the highest moral integrity and piety was entrusted with guiding the affairs of the community. The ideal, then, is a society governed not by man-made laws but by God's law in which the whole of life, all human activities, are subject to God's will. The concept of balance between all aspects of life (leisure, worship, work) is of central concern. Prayer, five times daily, permeates all of life and as prayer can be offered wherever the Muslim is, at work or at play, not only in a mosque, this sanctifies all space, as Muhammad said, “The whole world is a Mosque.” Islam also recognizes that the world of nature is valued by God, and needs to be conserved not exploited, so respect for nature is also part of this balance, which is itself an aspect of tawhid (oneness or balance).

In practice, there are different understandings of how sharia is to be understood and implemented in society as well as different views of how government should be organized. There are some Muslims who believe that the combination of temporal and spiritual authority under Muhammad in Medina post-622 C.E. was circumstantial, not a binding precedent for Muslims for all time. Throughout the world today, there are Muslim monarchies (some constitutional, some quasi-absolute), republics, and one-party states under dictatorial rule. The Islamic Republic of Iran vests ultimate power in the senior religious scholars. The former Taliban regime in Afghanistan (1996 – 2001) gave absolute authority to a religious leader, Mullah Omar (as the “best amongst us”) and remarkably was regarded by some Muslims as the only authentic Islamic state in the world, others being considered corrupt or infidel. Saudi Arabia is often described as an absolute monarchy but strictly speaking the religious scholars can remove a ruler if he transgresses sharia. There are some Muslims who contend that democracy is un-Islamic, others who equate shura with democracy. Opponents of democracy cite verses of the Qur'an that appear to reject majoritarianism (Qur’an 12:21; 12:103), criticize democratic states as elevating human over divine law, while the principle that anyone can stand for election means that ungodly people might seek power for corrupt reasons.[4] Some Muslim states have reservations or have passed amendments regarding various clauses of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHE) and of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, arguing that this contravenes sharia.[3] Other Muslims believe that, properly interpreted, there is no clash between international human rights and the sharia on such issues as freedom of belief and women's rights. Some Muslims say that the UDHR ignores God's rights (haq Allah) in favor of human rights (haq Adami), instead of balancing divine rights and human duty.[4]

Islamic law and Muslim Society

Sharia is Islamic law preserved through Islamic scholarship. The Qur'an is the foremost source of fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence); the second is the Sunnah (the practices of the Prophet, as narrated in reports of his life). The Sunnah is not itself a text like the Qur'an, but is extracted by analysis of the hadith (Arabic for "report," hadith is technically singular but the plural ahadith is rarely used in English) texts, which contain narrations of the Prophet's sayings, deeds, and actions of his companions he approved.

Islamic law covers all aspects of life, from the broad topics of governance and foreign relations all the way down to issues of daily living. Islamic law at the level of governance and social justice only applies where the government is Islamic.

According to Islam, sharia is divinely revealed. It is understood as protecting five things: faith, life, knowledge, lineage, and wealth. However, it is by no means a rigid system of laws. There are different schools of thoughts and movements within Islam that allow for flexibility. Moreover, Islam is a diverse religion as many cultures have embraced it. The following verse from the Qur'an sets out the ideal for Muslim life:

It is not righteousness that ye turn your faces towards east or west; but it is righteousness to believe in God and the Last Day, and the Angels, and the Book, and the Messengers; to spend of your substance, out of love for Him, for your kin, for orphans, for the needy, for the wayfarer, for those who ask, and for the ransom of slaves; to be steadfast in prayer, and practice regular charity; to fulfill the contracts which ye have made; and to be firm and patient, in pain (or suffering) and adversity, and throughout all periods of panic. Such are the people of truth, the God-fearing (2:177).

The Muslim community is defined as that which prohibits evil and promotes the good (3:110).

Apostasy (riddah) and blasphemy

Islamic communities, like other religious communities, often exclude apostates and blasphemers from the community of believers. Since Islam may be the state religion (or the state may be constituted as an Islamic state), punishment may have legal sanction. Historically, there has been a close affinity between apostasy and treason, since to question the truth of Islam could undermine the very fabric of the state's social and legal system.

In orthodox Islamic theology, conversion from Islam to another religion is forbidden and punishable by death. Apostasy is public disloyalty towards Islam by anyone who had previously professed the Islamic faith (private doubt or even repudiation will not be punished). Blasphemy (no technical term in Arabic) is showing disrespect or speaking ill of any of the essential principles of Islam. There is no sharp distinction made between these concepts, as many believers feel that there can be no blasphemy without apostasy.

In the period of Islamic empire and in places today where Islam is the state religion, apostasy was considered treason, and was accordingly treated as a capital offense; death penalties were carried out under the authority of the Caliph. Today apostasy is punishable by death in the countries of Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Yemen, Iran, Sudan, Pakistan, and Mauritania. Blasphemy is also an offense in many of these countries.

In most of these countries, such laws are invoked only sporadically and selectively; convictions tend to be reversed at a higher level, or if not reversed, those convicted may be allowed to leave the country. Some Islamic countries, notably, Saudi Arabia, Iran under the Islamic Republic, Afghanistan under the Taliban, and Sudan, have been willing to enforce laws and punishments against apostasy and blasphemy. In each of these countries, Islamist regimes that insist on a literal interpretation of Qur'anic penalties are estimated to have executed, flogged, and imprisoned hundreds or thousands of people believed to be apostates or blasphemers.

Other punishments prescribed by sharia (depending on interpretation) may include the annulment of marriage with a Muslim spouse, the removal of children, the loss of property and inheritance rights, or other sanctions.

Here as elsewhere in Islam, scholars disagree on specific applications of core principles, with some prominently advocating a punitive approach to "exclusionary" issues and others tending to de-emphasize such questions. Some traditions depict Muhammad ordering the execution of apostates. However, he also pardoned some. Famously, after the fall of Mecca he pardoned Abdullah Ibn Sa'd Ibn Abi Sarh, who had deliberately altered the Qur'an and when Muhammad appeared not to notice, denounced him as a fraud.

Islamic calendar

Islam dates from the Hijra, or migration from Mecca to Medina. This is year 1, AH (Anno Hegira)—which corresponds to 622 C.E. Before this, Muhammad's followers had been known as “believers” (Muminun). The Islamic calendar is lunar, but differs from other such calendars (e.g. the Celtic calendar) in that it omits intercalary months, being synchronized only with lunation, but not with the solar year, resulting in years of either 354 or 355 days. This omission was introduced by Muhammad because the right to announce intercalary months had led to political power struggles. Therefore Islamic dates cannot be converted to the usual c.e. dates simply by adding 622 years. Islamic holy days fall on fixed dates of the lunar calendar, which means that they occur in different seasons in different years.

Schools of Islam

There are a number of schools or traditions within the broader Islamic tradition, each of which have significant theological and legal differences from each other. The major branches are Sunni and Shi'a, with Sufism often considered as a third, although more properly it bridges both.

Sunni Islam

The Sunni school of Islam is the largest (some 80 to 85 percent of all Muslims are Sunni). Sunnis generally recognize four legal traditions (madhabs): Maliki, Shafi'i, Hanafi, and Hanbali. These schools predominate in certain areas; for example, Hanbali in Saudi Arabia, Hanafi in South Asia, Maliki in North Africa and Shafi'i in Kurdistan, Egypt, Yemen, Indonesia, Thailand, Singapore, and the Philippines. All four schools accept the validity of the others and Muslims choose any one that he/she thinks is agreeable to his/her ideas. Most Sunnis follow one of these, but they are free to consult other schools and also to choose to follow their advice or ruling. There are also several orthodox theological or philosophical traditions (kalam). Two smaller madhab are also recognized (historically, there have been others), the Ibadi (predominant in Oman, usually regarded as neither Sunni nor Shi'a) and the Thahiri.

Shi'a Islam

Shi'a Muslims differ from the Sunni in rejecting the authority of the first three caliphs. They honor different traditions (hadith) and have their own legal traditions. The Shi'a consist of one major school of thought known as the Ithna Ashariyya or the "Twelvers," and a few smaller schools, of which the largest are the Ismailis or the "Seveners" and the Zaydis or the "Fivers" (predominant in the Yemen). The Fivers parted company from the majority after the death of the fourth Imam, and the Seveners after the death of the sixth Imam, when the succession was disputed on both occasions. The term Shi'a is usually taken to be synonymous with the Ithna Ashariyya/Twelvers. Most Shi'a live in Iran, Iraq, and Lebanon. The living Imam of the Ismailis, whom they believe is infallible, the Aga Khan, is a Pakistani citizen. The Zaydis also had a living Imam until 1962 when Yemen became a republic. The last Zaydi Imam, Muhammad al-Badr (1926 – 1996) died in exile. The Zaydis did not regard their Imams as infallible or as divinely guided. The Ithna Ashariyya believe that their last Imam, al-Mahdi, was assumed into “heaven” in about 940 C.E., after which the leadership of the community devolved to the senior religious scholars, the mujtahidun or Ayatollahs (Ayahtollah means “sign of God,” who are his eyes and ears on earth). The most senior may be given the designation hujjat-al-islam (proof of Islam), or even marja' al-taqlid al-mutlaq (absolute point of reference). Shi’a believe that there never will be a perfectly just society until al-Madhi returns to earth and ushers in the kingdom of peace. The dominant legal school for the Ithna Ashariyya, Jafari, is named after the sixth Imam, al-Jafar (699 – 765) whose scholarly reputation was such that leading Sunni scholars, including Malik (died 796) and Hanbal (died 767) studied under him.

Clashes among Sunni and Shi’a

Sunni and Shi'a have often clashed. Some Sunni believe that Shi'a are heretics while many other Sunni recognize Shi'a as fellow Muslims. According to Shaikh Mahmood Shaltoot, head of the al-Azhar University in the middle part of the twentieth century, "the Ja'fari school of thought, which is also known as al-Shi'a al- Imamiyyah al-Ithna Ashariyyah (i.e., The Twelver Imami Shi'ites) is a school of thought that is religiously correct to follow in worship as are other Sunni schools of thought." Al-Azhar later distanced itself from this position. However, in July 2005 over 150 internationally renowned scholars representing Sunni and Shi'a Islam met in Amman under the patronage of the king of Jordan and mutually recognized the six Sunni and two Shi'a schools (Jafari, or Twelver, and Zaydi or Fiver) and condemned anyone who declares any member of these schools an apostate. Islam's commitment to tawhid (unity or oneness) means that ideally there is only one ummah (community or nation) and Muslims have often tried to find ways of reconciling their differences and of bridging divides.

Modern Movements

Traditionalist

Wahhabis, as they are known by non-Wahhabis, are a more recent group. They prefer to be called the Ikhwan, or Brethren, or sometimes Salafis (the term implies a return to the origins of Islam, the pure, earliest days) or muwahiddun (Unitarians). Wahhabism is a movement founded by Muhammad ibn Abd al Wahhab in the eighteenth century in what is present-day Saudi Arabia. They classify themselves as Sunni and follow the Hanbali legal tradition (but exclusively, without consulting other schools). However, some regard other Sunnis as heretics. They are recognized as the official religion of Saudi Arabia and have had a great deal of influence on the Islamic world due to Saudi control of Mecca and Medina, the Islamic holy places, and due to Saudi funding for mosques and schools in other countries. The Wahhabis are also described as “traditionalist” and are anti-Sufi regarding Sufis as too lax in observing Islam's outer rituals, too concerned with inner renewal and dangerously close to elevating not only Muhammad but also their teachers to semi-divine status. The authority, too, of Sufi sheikhs and the role of their shrines as centers for pilgrimage threatens the centralized authority of the Saudi government as guardians of the Sacred Cities, so Sufism also presents a political challenge. Wahhabis represent Sufi Islam as heterodox and suggest that it represents a movement towards Christianity and away from Islam. Such criticism can be found in the earlier writing of ibn Taymiyya (died 1328), who is popular among conservative Muslims (and cited by Osama bin Laden).

There are several significant movements that aim to create authentic Muslim societies, including governmental and legal systems, such as the Ikhwan-ul-Muslimin (Muslim Brotherhood) founded by Hassan al-Banna (1906 – 1949), the Jamaati-i-Islam (community of Islam) founded by Abu'l A'la Mawdudi (1903 – 1979) and the hizb-ut-tahrir al-islami (Islamic Liberation Party) founded by Taqiuddin an-Nabhana (1909 –1977). All these have, at different times and in various Muslim countries, had some electoral success. Jamaati members have held (or hold) Cabinet posts in Pakistan and Bangladesh. The Brotherhood is banned in Egypt but its candidates stand as independents, gaining 88 out of 454 seats in the election of November 2005. These parties aim to achieve their goals by constitutional means. Believing that Islam is also the answer to the problems of non-Muslim society, some of their supporters also engage in dialogue with non-Muslims and in educational and missionary activities in Europe and North America. These movements also believe that the nation-state is alien in Islam, so while their short-term agenda is to transform various Muslim nation-states such as Egypt and Pakistan into authentic Islamic states, their long-term goal is the creation of a single international Islamic order. They are usually termed “neo-traditionalist” since unlike the traditionalists they leave some scope for the construction of new Islamic models and do not only seek to replicate old ones.[5]

Jihadist

Some Muslims have split from these movements arguing that use of violence is justified to further the goal of Islamization. Such groups include the Egyptian Islamic Jihad, which assassinated President Sadat in 1981 (condemned for signing a peace treaty with the State of Israel in 1979) and Osama bin Laden's Al-Qaeda network, which regards the West as Islam's enemy (thus, all Westerners are legitimate targets whether civilian or military). Known as jihadists (or fundamentalists) they rely on such Qur'anic verses as Qur’an 9:5 and 2:216, and justify aggression (taking the initiative), not merely defense. These Muslims are all anti-Sufi. All of the above are regarded as Islamist, or fundamentalist. The term “fundamentalist” is problematic however, partly because of its origin in Christian discourse (where it has a purely theological significance; Islamism is political), but also because all Muslims actually hold beliefs that are remarkably similar to those of conservative Christians in terms of the infallibility of scripture, Jesus' Virgin Birth (in which, based on Qur’an 3:47 and 3:59, most Muslims believe), as well as moral values. Jihadists claim to be the successors of the early Kharijites, who assassinated Ali ibn Abi Talib and of the medieval Assassins.

Many Muslim rulers, however, believed it their duty to extend Muslim rule throughout the world. The concept of jihad (which means to strive) was sometimes used to describe this process, which justified aggression against non-Muslims provided that there was a good chance of success. Most Qur'anic usages of the term jihad do not refer to war but to spiritual struggle or to the struggle to establish social justice, such as 22:77–78, "believers, bow down and prostrate yourselves in worship of your Lord, and work righteousness, that you may succeed and strive (jihad) in the cause of God.” Other verses have been interpreted to refer to armed struggle to establish or extend Islamic rule, such as "Go ye forth, (whether equipped) lightly or heavily, and strive and struggle, with your goods and your persons, in the cause of Allah. That is best for you, if ye (but) knew" (9:41). Although the term is used to describe armed struggle or war to extend God's rule, the translation as “holy war” is inaccurate; it renders only one of the many meanings of the Arabic word. There are many Muslims who believe that the Qur'an only permits defense (see Qur’an 22:39–40; 2:190), but there are some who argue that aggression is permitted by such verses as 9:5 and 2:216 (referred to as the “sword verses”). The standard rebuttal to this claim is that the above verses were revealed during an existing conflict between Muslims as defenders and their enemies, who had attacked them. It is noteworthy that the earliest guidelines on the conduct of war in Islam protect civilians, priests, monks, places of worship, crops, and animals, permitting armed action only against military personnel. Although not found in the oldest traditions, there are popular sayings of Muhammad that elevate the spiritual or greater (jihad-al-akbar) jihad, above the military or lesser (jihad-al-asghar) jihad.[4]

Progressive

Another trend in modern Islam is sometimes called progressive, liberal, or secular Islam. Followers may be called Ijtihadists. They may be either Sunni or Shi'a, and generally favor the development of personal interpretations of the Qur'an and hadith often rejecting the notion of an “Islamic state.” Pioneers of liberal Islam include Muhammad Iqbal (1877 – 1938) and Muhammad 'Abduh (1849 – 1905).[6] One contemporary scholar, Farid Esack, describes progressive Islam as an Islam that seeks to transform unjust societies into just ones, and people as objects of exploitation into “subjects of history.”[6]

Secular Muslims regard Islam as a way of life and source of moral guidance, not as a political system. Tibi calls din wa dawla (unity of religion and state), the "cardinal principle of fundamentalist (or political) Islam" a "fiction," (163) and says that Islam is "religious belief, not ideology," "a source of ethics for humans and of orientation in their conduct."[5]

Differences between fundamentalist and liberal and progressive Muslims include the following: the former say that the right of Muslim men to marry four wives is sacrosanct, the latter that the ideal is monogamy and that the Qur'an's permission for polygamy was not meant to be eternally binding (see, Qur’an 4:3); the former say that women have equal but different rights from men, the latter that both sexes have identical rights. Traditionalists are more likely to be defensive both about the historical record, and about contemporary practice, claiming that Islam has always and everywhere treated minorities and women well and has honored human rights. Progressives are likely to argue that Muslims have often fallen short of their own ideals, that what has passed as official Islam has rather served special interests and that the true message of Islam has to be separated from how Islam has been interpreted and practiced. Their orientation is futuristic, not historical. Sardar, a progressive scholar, writes, "Islam is perforce a future-oriented world-view.[7] Tibi argues, though, that traditionalists are really not interested in history, because their belief in Islam's essential timelessness "leaves no room for the study of history."[5] Mernissi says that authoritarian Muslim regimes manipulate history because they fear that Muslims would find, in history, resources to rebel. "If we had a true understanding of our past," she says, "we would feel less alienated by the West and its democracy."[3]

Sufi Islam

Sufism is a spiritual practice followed by both Sunni and Shi'a. Sufis generally feel that following Islamic law is only the first step on the path to perfect submission; they focus on the internal aspects of Islam, such as perfecting one's faith and fighting one's own ego.

Most Sufi orders, or tariqa, can be classified as either Sunni or Shi'a. There are also some very large groups or sects of Sufism that are not easily categorized as either Sunni or Shi'a, such as the Bektashi. Sufis are found throughout the Islamic world, from Senegal to Indonesia.

Religions based on Islam

The following groups consider themselves to be Muslims, but are not considered Islamic by the majority of Muslims or Muslim authorities:

- The Nation of Islam

- The Zikris

- The Qadianis (or Ahmadiyya)

The following consider themselves Muslims but acceptance by the larger Muslim community varies:

One very small Muslim group, based primarily in the United States, follows the teachings of Rashad Khalifa (1935 – 1990) and calls itself the "Submitters." They reject hadith and fiqh, and say that they follow the Qur'an alone. There is also an even smaller group of Qur'an-only Muslims who claim to represent the authentic teachings of Rashad Khalifa and seem to have split from the Submitters. Most Muslims of both the Sunni and the Shi’a sects consider this group to be heretical.

The following religions are said by some to have evolved or borrowed from Islam, in almost all cases influenced by traditional beliefs in the regions where they emerged, but consider themselves independent religions with distinct laws and institutions:

- Babism

- Bahá'í Faith

- Yazidi

The claim of the adherents of the Bahá'í Faith that it represents an independent religion was upheld by the Muslim ecclesiastical courts in Egypt during the 1920s. As of January 1926, their final ruling on the matter of the origins of the Bahá'í Faith and its relationship to Islam was that the Bahá'í Faith was neither a sect of Islam, nor a religion based on Islam, but a clearly-defined, independently-founded faith. This was seen as a considerate act on the part of the ecclesiastical court and in favor of followers of Bahá'í Faith since the majority of Muslims would regard a “religion based on Islam” as a heresy.

Some see Sikhism as a syncretic mix of Hinduism and Islam. However, its history lies in the social strife between local Hindu and Muslim communities, during which Sikhs were seen as the "sword arm" of Hinduism. The philosophical basis of the Sikhs is deeply rooted in Hindu metaphysics and certain philosophical practices. Sikhism also rejects image worship and believes in one God, just like the Bhakti reform movement in Hinduism and also like Islam does.

The following religions might have been said to have evolved from Islam, but are not considered part of Islam, and no longer exist:

- The religion of the medieval Berghouata

- The religion of Ha-Mim

Islam and other religions

The Qur'an contains both injunctions to respect other religions, and to fight and subdue unbelievers. Some Muslims have respected Jews and Christians as fellow "peoples of the book" (monotheists following Abrahamic religions), and others have reviled them as having abandoned monotheism and corrupted their scriptures. At different times and places, Islamic communities have been both intolerant and tolerant. Support can be found in the Qur'an for both attitudes.

The classical Islamic solution was a limited tolerance—Jews and Christians were to be allowed to privately practice their faith and follow their own family law. They were called Dhimmis, and they had fewer legal rights and obligations than Muslims although it should be remembered that in the same era, minorities in many other societies either had no rights or limited rights, such as Jews in Europe or non-Orthodox Christians in the Byzantine Empire.

The Islamic state during the three dynastic caliphates and in such places as Spain and India, when Muslims dominated these regions, was often more tolerant than many other states of the time, which insisted on complete conformity to a state religion. When Jews and other dissident groups in parts of Europe could not hold any government post, Jews and Christians within the Muslim world could and did occupy senior administrative posts, such as state treasurer and vizier (which perhaps best translates as Secretary of State). Jews expelled from Europe, or who fled because of persecution, found refuge in the Muslim world. Sometimes, Jews fleeing from harsher Muslim rule in one region found refuge elsewhere, such as when Jews fleeing Spain in 1492 moved to Egypt and to the Balkans, where they were welcomed. Lewis comments that Ottoman “Sultan Bayezid II ... permitted and even encouraged great numbers of Jews from Spain and Portugal to settle in the Ottoman realms and to rebuild their lives after their expulsion from their homelands.”[8] The record of contemporary Muslim-majority states is mixed. Some are generally regarded as tolerant, while others have been accused of intolerance and human rights violations.

History

Islamic history began in Arabia in the seventh century with the emergence of the prophet Muhammad. Within a century of his death, an Islamic state stretched from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to central Asia in the east which, however, was soon torn by civil wars (fitnas). After this, there would always be rival dynasties claiming the caliphate, or leadership of the Muslim world, and many Islamic states or empires offering only token obedience to an increasingly powerless caliph.

Nonetheless, the later empires of the Abbasid caliphs and the Seljuk Turks were among the largest and most powerful in the world. After the disastrous defeat of the Byzantines at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, Christian Europe launched a series of crusades and for a time captured Jerusalem. Saladin, however, restored unity and defeated the Shi’ite Fatimids. Islam also spread to many places where no military conquest ever took place, such as Indonesia (the largest Muslim population). While non-Muslims often accused Muslims of spreading the faith violently, compelling people to either convert or die (based on Qur’an 9:29), research has shown that Islam's success was due to “the un-remitted labours of Muslim missionaries.”[9] Qur’an verse 2:256 forbids the use of force in preaching Islam. Significant portions or the whole of Spain, Sicily, and the Balkans were all under Muslim rule for substantial periods; respectively 711 until the last stronghold fell in 1492, 827 to 1091, and from about 1389 until the end of the Balkan War (1913).

From the fourteenth to the seventeenth century, one of the most important Muslim territories was the Mali Empire, whose capital was Timbuktu. In the eighteenth century, there were three great Muslim empires: the Ottoman in Turkey, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean; the Safavid in Iran; and the Moghul Empire in India. By the nineteenth century, these realms had fallen under the sway of European political and economic power. Following World War I, the remnants of the Ottoman Empire were parceled out as European protectorates or spheres of influence. Islam and Islamic political power revived in the twentieth century largely due to the oil-generated wealth of several Muslim states. However, the relationship between the West and the Islamic world remains uneasy. During the colonial period, Muslims institutions and systems were largely replaced by European ones. Thus, the challenge facing many Muslims is how to re-construct Islamic systems and often a choice between two alternatives exists. The first is to try to recover ideals and models from Islam's past, from the pure, early days (the Salafi solution). The second is to identify what are the principles on which the Salafis built, and to then apply these to today's needs. Thus, a salafist will insist on amputation as the penalty for theft in any authentic Islamic state (Qur’an 5:38), while a progressive will argue that a punishment that deters is consistent with Islamic principles (also, the Qur'an's bias towards mercy will be cited Qur’an 42:40).

Contemporary Islam

Although the most visible movement in Islam in recent times has been Islamism, or fundamentalism (such as the Muslim Brotherhood), there are a number of liberal movements within Islam that seek alternative ways to align the Islamic faith with contemporary questions.

Early sharia had a much more flexible character than is currently associated with Islamic jurisprudence, and many modern Muslim scholars believe that it should be renewed, and the classical jurists should lose their special status. This would require formulating a new fiqh suitable for the modern world, for example, as proposed by advocates of the Islamization of knowledge, pioneered by Isamail Ragi al-Faruqi (1921 – 1986) and would deal with the modern context. One vehicle proposed for such a change has been the revival of the principle of ijtihad, or independent reasoning by a qualified Islamic scholar, which has lain dormant for centuries. This movement does not aim to challenge the fundamentals of Islam; rather, it seeks to clear away misinterpretations and to free the way for the renewal of the previous status of the Islamic world as a center of modern thought and freedom.

The claim that only "liberalization" of the Islamic sharia law can lead to distinguishing between tradition and true Islam is countered by many Muslims with the argument that any meaningful “fundamentalism” will, by definition, reject non-Islamic cultural inventions—for instance, acknowledging and implementing Muhammad's insistence that women have God-given rights that no human being may legally infringe upon. Proponents of modern Islamic philosophy sometimes respond to this by arguing that, as a practical matter, "fundamentalism" in popular discourse about Islam may actually refer, not to core precepts of the faith, but to various systems of cultural traditionalism.

The demographics of Islam today

A comprehensive 2009 demographic study of 232 countries and territories reported that 23 percent of the global population, or 1.57 billion people, are Muslims. Of those, it is estimated over 75–90 percent are Sunni and 10–20 percent are Shi'a.[10] Islam is growing faster numerically than any of the other major world religions.[11] This is attributed either to the higher birth rates in many Islamic countries (six out of the top-ten countries in the world with the highest birth rates have a Muslim majority) and/or high rates of conversion to Islam.

Only 18 percent of Muslims live in the Arab world; 20 percent are found in Sub-Saharan Africa; about 30 percent in the Indian subcontinental region of Pakistan, India, and Bangladesh; and the world's largest single Muslim community (within the bounds of one nation) is in Indonesia. There are also significant Muslim populations in China, Europe, central Asia, and Russia.

Muslims in Europe and North America

France has the highest Muslim population of any nation in Europe, with up to 6 million Muslims (10 percent of the population). Albania is said to have the highest proportion of Muslims as part of its population in Europe (70 percent), although this figure is only a (highly contested) estimate.

The number of Muslims in North America is variously estimated as anywhere from 1.8 to 7 million. Traditionally, Muslims were not encouraged to live in non-Muslim majority societies but for economic reasons many have migrated to non-Muslim states, some as political refugees. There is a great deal of discussion in contemporary Islamic discourse on Muslims as minorities. Following the attack on the New York World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, and the London suicide bombing of July 7, 2005, questions have been regarding the loyalty of some Muslims living in the West towards the countries of which they are citizens.

Fervent Muslims in the non-Muslim world

Fervent Muslims living in the non-Muslim world have had differing views on their roles as citizens. Mohammad Sidique Khan, one of the men responsible for the July 7, 2005, London bombing, born and raised in the United Kingdom, spoke of being Muslim first and British second, “Your democratically elected governments continuously perpetuate atrocities against my people all over the world,” and "We will respond in kind to all those who took part in the aggressions against Iraq, Afghanistan, and Palestine," he said (video recording broadcast by al-Jazeera television station.[12]

Other Muslims argue that the only justification for living in the West is to work to make the West Islamic and to promote reform within the Muslim world. Al-Faruqi argued that migration could only be understood as a providential opportunity to both invite non-Muslims to become Muslim and to reform “Islam among Muslims as well.”[13]

Other Muslims advise that Muslims are obliged to fully obey the laws of the state of which they are citizens or they should leave.[4] Some Westerners have questioned whether Islam is compatible with Western values.[14][15]

The Harvard academic, Samuel P. Huntington, predicted in a 1993 Foreign Affairs article that the next great clash or conflict would be between Islam (possible in alliance with neo-Confucian states, what he calls the Confucian-Islamic connection) and the West. Italian Prime Minister, Silvio Burlusconi remarked in 2001 that European civilization was far superior to any other, especially Islamic. Many see the War on Terror, launched by President Bush after September 11, as primarily a war against Islam. Daniel Pipes, formerly as adviser to the Bush administration, argues that the war is indeed a war on radical or militant Islam.[16] Asking “whom are we fighting?” he replied, “Two main culprits have emerged since September 11: terrorism and Islam. The truth, more subtle, lies between the two—a terroristic version of Islam.” Osama bin Laden and others, he said, “are all fervent Muslims acting on behalf of their religion.”[17][18]

Symbols of Islam

Green is commonly used when representing Islam. It is much used in decorating mosques, tombs, and various religious objects. Some say this is because green was the favorite color of Muhammad and that he wore a green cloak and turban. Others say that it symbolizes vegetation. Some say that after Muhammad, only the caliphs were allowed to wear green turbans. In Qur'an 18:31, it is said that the inhabitants of paradise will wear green garments of fine silk.

The reference to the Qur'an is verifiable; it is not clear if the other traditions are reliable or mere folklore. However, the association between Islam and the color green is firmly established now, whatever its origins may have been.

- The color green is absent from medieval European coats of arms as during the Crusades, green was the color used by their Islamic opponents.

- In the palace of Topkapi, in Istanbul, there is a room with relics of Muhammad. One of the relics, kept locked in a chest, is said to have been Muhammad's banner, under which he went to war. Some say that this banner is green with golden embroidery; others say that it is black and others think there is no banner in the chest at all.

In early accounts of Muslim warfare, there are references to flags or battle standards of various colors: black, white, red, and greenish-black. Later Islamic dynasties adopted flags of different colors:

- The Umayyads fought under white banners

- The Abbasids chose black

- The Fatimids used green

- Various countries on the Persian Gulf have chosen red flags

These four colors, white, black, green, and red, dominate the flags of Arab states.[19]

The crescent and star are often said to be Islamic symbols, but flag historians say that they were the insignia of the Ottoman Empire, not of Islam as a whole.

Notes

- ↑ Some Shi'a Muslim sects, such as Twelvers and Zaydis, do not believe in absolute predestination (Qadar), since they consider it incompatible with Divine Justice. Neither do they believe in absolute free will since that contradicts God's Omniscience and Omnipotence. Rather they believe in "a way between the two ways" (amr bayn al‑'amrayn) believing in free will, but within the boundaries set for it by God and exercised with His permission.

- ↑ The Egyptian Islamic Jihad group claims, as did a few long-extinct early medieval Kharijite sects, that Jihad is the "sixth pillar of Islam." Some Ismaili groups consider "Allegiance to the Imam" to be the so-called sixth pillar of Islam.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Fatima Mernissi, Islam and Democracy: Fear of the Modern World (Cambridge, MA: Perseous Books, 1994, ISBN 0201624834).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Clinton Bennett, Muslims and Modernity: An Introduction to the Issues and Debates (London: Continuum, 2005, ISBN 082645481X).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Bassam Tibi, The Challenge of Fundamentalism: Political Islam and the New World Disorder (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1998, ISBN 0520088689).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Omid Safi (ed.), Progressive Muslims: On Justice, Gender and Pluralism (Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2003, ISBN 978-1851683161).

- ↑ Ziauddin Sardar, Islamic Futures: The Shape of Ideas to Come (London: Mansell, 1985, ISBN 0720117313).

- ↑ Bernard Lewis, The Jews of Islam (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984, ISBN 0691008078).

- ↑ Sir Thomas Walker Arnold, The Preaching of Islam (Forgotten Books, 2010, ISBN 978-1440081316).

- ↑ Mapping the Global Muslim Population Pew Research Center’s Forum on Religion & Public Life, October 7, 2009. Retrieved March 18, 2022.

- ↑ Trends in Religion Signs and Wonders. Retrieved March 18, 2022.

- ↑ London bomber: Text in full BBC News, September 1, 2005. Retrieved March 18, 2022.

- ↑ Barbara Daly Metcalf, Making Muslim Space in North America and Europe (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1996, ISBN 0520204042).

- ↑ Tony Blankley, The West’s Last Chance: We Will Win the Clash of Civilizations (Washington, DC: Regnery Publication, 2005, ISBN 0895260158).

- ↑ Robert Spencer, The Politically Incorrect Guide to Islam (Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing, 2005, ISBN 0895260131).

- ↑ Daniel Pipes was a member of the U.S. Institute for Peace from 2003 until early 2005 when the Senate failed to re-confirm his nomination.

- ↑ Daniel Pipes, Aim the War on Terror at Militant Islam Los Angeles Times, January 6, 2002. Retrieved March 18, 2022.

- ↑ Daniel Pipes, Militant Islam Reaches America (New York: W.W. Norton, 2003, ISBN 0393325318).

- ↑ Edmund Midura, Flags of the Arab World Saudi Aramco World March/April 1978. Retrieved March 18, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Arberry, A. J. The Koran Interpreted: A Translation. New York: Touchstone/Simon and Schuster, 1996. ISBN 0684825074

- Arnold, Sir Thomas Walker. The Preaching of Islam. Forgotten Books, 2010. ISBN 978-1440081316

- Bennett, Clinton. Muslims and Modernity: An Introduction to the Issues and Debates. London: Continuum, 2005. ISBN 082645481X

- Blankley, Tony. The West’s Last Chance: We Will Win the Clash of Civilizations. Washington, DC: Regnery Publication, 2005. ISBN 0895260158

- Encyclopedia of Islam. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 2003. ISBN 9004128344

- Huntington, Samuel P. “The Clash of Civilizations?” Foreign Affairs 72(3) (Summer 1993): 22–49.

- Kramer, Martin (ed.). The Islamism Debate. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-9652240248

- Kurzamn, Charles (ed.). Liberal Islam: A Sourcebook. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0195116224

- Lewis, Bernard. The Jews of Islam. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984. ISBN 0691008078

- Mernissi, Fatima. Islam and Democracy: Fear of the Modern World, translated by Mary Jo Lakeland. Cambridge, MA: Perseous Books, 1994. ISBN 0201624834

- Metcalf, Barbara Daly. Making Muslim Space in North America and Europe. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1996. ISBN 0520204042

- Pipes, Daniel. Militant Islam Reaches America. New York: W.W. Norton, 2003. ISBN 0393325318

- Rahman, Fazlur. Islam. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979. ISBN 0226702812

- Safi, Omid (ed.). Progressive Muslims: On Justice, Gender and Pluralism. Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 2003. ISBN 978-1851683161

- Sardar, Ziauddin. Islamic Futures: The Shape of Ideas to Come. London: Mansell, 1985. ISBN 0720117313

- Spencer, Robert. The Politically Incorrect Guide to Islam. Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing, 2005. ISBN 0895260131

- Tibi, Bassam. The Challenge of Fundamentalism: Political Islam and the New World Disorder. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1998. ISBN 0520088689

External links

All links retrieved December 13, 2024.

- Muslim Heritage, Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation, UK.

- International Museum of Muslim Cultures, Jackson, MS.

- Islamic Philosophy Online

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.