Sudan

Republic of the Sudan جمهورية السودان Jumhūrīyat as-Sūdān |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: النصر لنا Victory is ours |

||||||

| Anthem: نحن جند لله جند الوطن We are the soldiers of God and of our land |

||||||

| Capital | Khartoum | |||||

| Largest city | Omdurman | |||||

| Official languages | Arabic, English | |||||

| Demonym | Sudanese | |||||

| Government | Federal provisional government | |||||

| - | Chairman of the Transitional Sovereignty Council | Abdel Fattah al-Burhan | ||||

| - | Deputy Chairman of the Transitional Sovereignty Council | Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Osman Hussein | ||||

| Legislature | Transitional Legislative Council | |||||

| Formation | ||||||

| - | Anglo-Egyptian Sudan colonization | 1899 | ||||

| - | Independence and end of the Anglo-Egyptian rule | January 1, 1956 | ||||

| - | Secession of South Sudan | July 9, 2011 | ||||

| - | Coup d'état | April 11, 2019 | ||||

| - | Constitutional Declaration | August 4, 2019 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 1,861,484 km² (17th) 718,723 sq mi |

||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2023 estimate | 49,197,555[1] (30th) | ||||

| - | 2008 census | 30,894,000 (disputed)[2] (40th) | ||||

| - | Density | 21.3/km² 55.3/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2019 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $209.412 billion[3] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $4,712[3] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $162.649 billion[3] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $3,763[3] | ||||

| Gini (2009) | 35.4[4] (96) | |||||

| Currency | Sudanese pound (SDG) |

|||||

| Time zone | Central Africa Time (UTC+2) | |||||

| Internet TLD | .sd | |||||

| Calling code | +249 | |||||

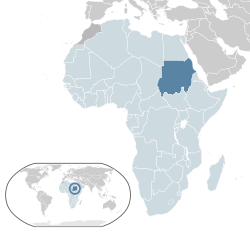

The Sudan (officially Republic of Sudan) is a country in Northeast Africa. It is bordered by Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the northeast, Eritrea and Ethiopia to the east, South Sudan to the south, the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, and Libya to the northwest. Occupying a total area of 1,861,484 square kilometres (718,723 square miles), it is the third-largest country in Africa. Its capital and largest city is Khartoum.

Military regimes have dominated Sudanese politics since the country's independence from the United Kingdom in 1956. The remainder of the twentieth century saw two civil wars resulting in millions of deaths and millions displaced, due in large part to famine and disease. The chronic instability in Sudan holds much of the population at or below the poverty line. Sudan's border states have felt the effects of that country's near-constant fighting as they've been forced to provide shelter for fleeing refugees.

Though the Sudanese people have experienced decades of war, genocide, and poverty, they hold on to hope, as is reflected in their national flag which has adopted the Pan-Arab colors first introduced in 1920; red, white, green and black. These colors reflect the heart and desires of the Sudanese people. Red represents the struggles and martyrs in the Sudan and the great Arab land; white stands for peace, optimism, light and love; black symbolizes the Sudan and the mahdija revolution during which a black flag was used; and green represents and symbolizes growth and prosperity.

Geography

Sudan is situated in northern Africa, with a 853 km (530 mi) coastline bordering the Red Sea. It is the third largest country on the continent (after Algeria and DR Congo). Sudan is bordered by Egypt to the north, the Red Sea to the northeast, Eritrea and Ethiopia to the east, South Sudan to the south, the Central African Republic to the southwest, Chad to the west, and Libya to the northwest. It is dominated by the Nile River and its tributaries.

Geographical regions

Northern Sudan, lying between the Egyptian border and Khartoum, has two distinct parts, the desert and the Nile Valley. To the east of the Nile lies the Nubian Desert; to the west, the Libyan Desert. They are similar—stony, with sandy dunes drifting over the landscape. There is virtually no rainfall in these deserts, and in the Nubian Desert there are no oases. In the west, there are a few small watering holes, such as Bir an Natrun, where the water table reaches the surface to form wells that provide water for nomads, caravans, and administrative patrols, although insufficient to support an oasis and inadequate to provide for a settled population. Flowing through the desert is the Nile Valley, whose alluvial strip of habitable land is no more than two kilometers wide and whose productivity depends on the annual flood.

Western Sudan is a generic term describing the regions known as Darfur and Kurdufan that comprise 850,000 square kilometers. Traditionally, this has been regarded as a single regional unit despite the physical differences. The dominant feature throughout this immense area is the absence of perennial streams; thus, people and animals must remain within reach of permanent wells. Consequently, the population is sparse and unevenly distributed.

Sudan's third distinct region is the central clay plains that stretch eastward from the Nuba Mountains to the Ethiopian frontier, broken only by the Ingessana Hills, and from Khartoum in the north to the far reaches of southern Sudan. Between the Dindar and the Rahad rivers, a low ridge slopes down from the Ethiopian highlands to break the endless skyline of the plains, and the occasional hill stands out in stark relief. The central clay plains provide the backbone of Sudan's economy because they are productive where settlements cluster around available water.

Northeast of the central clay plains lies eastern Sudan, which is divided between desert and semidesert and includes Al Butanah, the Qash Delta, the Red Sea Hills, and the coastal plain. Al Butanah is an undulating land between Khartoum and Kassala that provides good grazing for cattle, sheep, and goats. East of Al Butanah is a peculiar geological formation known as the Qash Delta. Originally a depression, it has been filled with sand and silt brought down by the flash floods of the Qash River, creating a delta above the surrounding plain.

Northward beyond the Qash lie the more formidable Red Sea Hills. Dry, bleak, and cooler than the surrounding land, particularly in the heat of the Sudan summer, they stretch northward into Egypt, a jumbled mass of hills where life is hard and unpredictable for the hardy Beja inhabitants. Below the hills sprawl the coastal plain of the Red Sea, varying in width from about 56 kilometers in the south near Tawkar to about twenty-four kilometers near the Egyptian frontier. The coastal plain is dry and barren. It consists of rocks, and the seaward side is thick with coral reefs.

The southern clay plains, which can be regarded as an extension of the northern clay plains, extend all the way from northern Sudan to the mountains on the Sudan-Uganda frontier, and in the west from the borders of Central African Republic eastward to the Ethiopian highlands.

The land rising to the south and west of the southern clay plain is referred to as the Ironstone Plateau (Jabal Hadid), a name derived from its laterite soils and increasing elevation. The plateau rises from the west bank of the Nile, sloping gradually upward to the Congo-Nile watershed. The land is well watered, providing rich cultivation, but the streams and rivers that come down from the watershed divide and erode the land before flowing on to the Nilotic plain flow into As Sudd. Along the streams of the watershed are the gallery forests, the beginnings of the tropical rainforests that extend far into Zaire.

Climate

Although Sudan lies within the tropics, the climate ranges from arid in the north to tropical wet-and-dry in the far southwest. Temperatures do not vary greatly with the season at any location; the most significant climatic variables are rainfall and the length of the dry season. Variations in the length of the dry season depend on which of two air flows predominates, dry northeasterly winds from the Arabian Peninsula or moist southwesterly winds from the Congo River basin.

The amount of rainfall increases towards the south. In the north there is the very dry Nubian Desert; in the south there are swamps and rainforest. Sudan’s rainy season lasts for about three months (July to September) in the north, and up to six months (June to November) in the south. The dry regions are plagued by sand storms, known as haboob, which can completely block out the sun. In the northern and western semi-desert areas, people rely on the scant rainfall for basic agriculture and many are nomadic, traveling with their herds of sheep and camels. Nearer the River Nile, there are well-irrigated farms growing cash crops.

Natural resources

Petroleum is Sudan's major natural resource. Additional resources include: natural gas, gold, silver, chromite, asbestos, manganese, gypsum, mica, zinc, iron, lead, uranium, copper, kaolin, cobalt, granite, nickel and tin.

The Nile is the dominant geographic feature of Sudan, flowing 3,000 kilometers from Uganda in the south to Egypt in the north. Most of the country lies within its catchment basin. The Blue Nile and the White Nile, originating in the Ethiopian highlands and the Central African lakes, respectively, join at Khartoum to form the Nile River proper that flows to Egypt. Other major tributaries of the Nile are the Bahr al Ghazal, Sobat, and Atbarah rivers.

Concerns

Desertification is a serious problem in Sudan. There is also concern over soil erosion. Agricultural expansion, both public and private, has proceeded without conservation measures. The consequences have manifested themselves in the form of deforestation, soil desiccation, and the lowering of soil fertility and the water table.[5]

The nation's wildlife is threatened by hunting. As of 2001, twenty-one mammal species and nine bird species were endangered, as well as two types of plants. Endangered species include: the waldrapp, northern white rhinoceros, tora hartebeest, slender-horned gazelle, and hawksbill turtle. The Sahara oryx has become extinct in the wild.[6]

History

Early history of Sudan

Three ancient Kushite kingdoms existed consecutively in northern Sudan. This region was also known as Nubia and Meroë. These civilizations flourished mainly along the Nile River from the first to the sixth cataracts. The kingdoms were influenced by Ancient Pharaonic Egypt. In ancient times, Nubia was ruled by Egypt from 1500 B.C.E., to around 1000 B.C.E. when the Napatan Dynasty was founded under Alara. It regained independence for the Kingdom of Kush although borders fluctuated greatly.

Christianity was introduced by missionaries in the third or fourth century, and much of the region was converted to Coptic Christianity. Islam was introduced in 640 C.E. with an influx of Muslim Arabs. Though the Arabs conquered Egypt, the Christian Kingdoms of Nubia managed to persist until the fifteenth Century.

A merchant class of Arabs became economically dominant in feudal Sudan. An important kingdom in Nubia was the Makuria. The Makuria reached its height in the eighth-ninth centuries. It was of the Melkite Christian faith, unlike its Coptic neighbors, Nobatia and Alodia.

Kingdom of Sennar

During the 1500s a people called the Funj conquered much of Sudan. This established the Kingdom of Sennar. By the time the kingdom was conquered by Egypt in 1820, the government was substantially weakened by a series of succession arguments and coups within the royal family.

Foreign control: Egyptian and British

In 1820, Northern Sudan came under the Egyptian rule by Muhammad Ali of Egypt. His sons Ismail Pasha and Mahommed Bey were sent to conquer eastern Sudan. The Egyptians developed Sudan’s trade in ivory and slaves.

Ismail Pasha, the khedive of Egypt from 1863-1879, attempted to extend Egyptian rule to the south, bringing in the British influence. Religious leader Muhammad al Abdalla, the self-proclaimed Messiah, sought to purify Islam in Sudan. He led a nationalist revolt against the British-Egyptian rule, which was successful. Both Egypt and Great Britain abandoned Sudan, leaving Sudan a theocratic Mahdist state.

In the 1890s the British sought to regain control of Sudan. Anglo-Egyptian military forces were successful in their endeavor. Sudan became subject to a governor-general appointed by Egypt with British consent. In reality, Sudan became a colony of Great Britain.

On January 19, 1899 Britain and Egypt signed an agreement under which the Sudan was to be administered jointly. In the 12 ensuing years, the Sudan's revenue had increased 17-fold, its expenditure tripled, and its budget reached a balanced state which was to be maintained until 1960. Sir Lee Stack, Governor-General of the Sudan was assassinated in the streets of Cairo in 1924, the result of mounting Egyptian nationalism in the period after World War I. Britain reacted by expelling all Egyptian officials from the Sudan.

Following the Anglo-Egyptian entente of 1936, a few Egyptians were allowed to return to the country in minor posts. Many Sudanese objected both to the return of the Egyptians and to the fact that other nations were deciding their destiny. This prompted the formation of the Graduates' Congress, under the leadership of Ismail al-Azhari.

From 1924, until independence in 1956, the British had a policy of running Sudan as two essentially separate colonies, the south and the north. However, two political parties had emerged within the country by 1945. These were the National Unionist Party led by al-Azhari, which demanded the union of the Sudan and Egypt and had the support of Sayed Sir Ali al- Mirghani, head of a powerful religious sect. The other party was the Umma Party, which was backed by Sayed Sir Abdur-Rahman al-Mahdi, and demanded unqualified independence and no links with Egypt.

Independence

Britain and Egypt signed an accord ending the condominium arrangement on February 12, 1953. The accord effectively agreed to grant Sudan self government within three years. Also included were provisions for a senate for the Sudan, a Council of Ministers, and a House of Representatives, elections to which was to be supervised by an international commission.

Elections were held during November and December 1953 and resulted in victory for the NUP, and its leader, Ismail al-Aihari, who became the Sudan's first Prime Minister in January 1954. British and Egyptian officers in the Sudanese civil service were quickly replaced by Sudanese nationals.

The nation's Parliament voted unanimously in December 1955 that the Sudan should become "a fully independent sovereign state." Foreign troops left the country on January 1, 1956, which was the same day a five-man Council of State was appointed to take over the powers of the governor general until a new constitution could be agreed upon.

First Sudanese civil war

The year before independence, a civil war began between Northern and Southern Sudan. Southerners, who knew independence was coming, were afraid the new nation would be dominated by the North.

The North of Sudan had historically closer ties with Egypt and was predominately Arab and Muslim. The South of Sudan was predominately Black, with a mixture of Christians and Animists. These divisions were emphasized by the British policy of ruling Sudan’s North and South separately. From 1924 it was illegal for people living above the 10th parallel to go further south, and people below the 8th parallel to go further north. The law was ostensibly enacted to prevent the spread of malaria and other tropical diseases that had ravaged British troops. It also prevented Northern Sudanese from raiding Southern tribes for slaves. The result was increased isolation between the already distinct north and south. This was the beginning of heated conflict simmering for many decades.

The resulting conflict was known as the First Sudanese Civil War which lasted from 1955 to 1972. The war ended officially in March 1972, when Colonel Numeiry signed a peace pact with Major-General Lagu, the Leader of the Anya-Nya rebels in the south, known as the Addis Ababa Agreement (A.A.A.). This brought a cessation of the north-south civil war and established a degree of self-rule. This led to a ten-year hiatus in the civil war. Under the Addis Ababa Agreement, Southern Sudan was given considerable autonomy.

Second Sudanese civil war

In 1983 the civil war was reignited following President Gaafar Nimeiry’s decision to circumvent the Addis Ababa Agreement, by attempting to create a Federated Sudan including states in Southern Sudan. This violated the Addis Ababa Agreement which had previously granted the South considerable autonomy. The Sudan People's Liberation Army formed in May 1983 as a result. Finally, in June 1983, the Sudanese Government under President Gaafar Nimeiry abrogated the Addis Ababa Peace Agreement.

The situation was exacerbated after al-Nimeiry went on to implement Sharia Law in September of the same year. In accord with this enactment, the penal code had been revised in order to link it "organically and spiritually" with Islamic Law. This changed the definition of crimes committed as being defined according to the Koran.

The civil war went on for more than 20 years, resulting in the deaths of 2.2 million Christians and Animists. It displaced roughly 4.5 million people within Sudan and into neighboring countries. It also damaged Sudan’s economy leading to food shortages resulting in starvation and malnutrition. The lack of investment during this time, particularly in the south, meant a generation lost access to basic health services, education, and jobs.

Peace talks between the southern rebels and the government made substantial progress in 2003 and early 2004. The Naivasha peace treaty was signed on January 9, 2005, granting Southern Sudan autonomy for six years, followed by a referendum about independence. It created a co-vice president position and allowed the north and south to split oil equally. It left both the North's and South's armies in place.

The United Nations Mission In Sudan (UNMIS) was established under UN Security Council Resolution 1590 in March 24, 2005. Its mandate is to support implementation of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement, and to perform functions relating to humanitarian assistance, protection and promotion of human rights. There was some hostility toward the UN being in Sudan. In greater hopes of peace, the International Observance in Sudan was formed. It consists of four nations, the U.S., Norway, Italy and Great Britain.

Secession of South Sudan

A referendum took place in Southern Sudan in January 2011, on whether the region should remain a part of Sudan or be independent. Voters from the worldwide South Sudanese diaspora were included. The result showed 98.9 percent in favor of secession.

Southern Sudan became an independent country, with the name of South Sudan, on July 9, 2011.[7]

Despite this result, many crucial issues are yet to be resolved, some of which requiring international intervention. The threats to people of South Sudan after referendum are numerous, with security topping the list. Other threats include disputes over the region of Abyei, control over oil fields, the borders, and the issue of citizenship.

Politics

Sudan has an authoritarian government in which all effective political power is in the hands of the President.

From 1983 to 1997, the country was divided into five regions in the north and three in the south, each headed by a military governor. After the April 6, 1985, military coup, regional assemblies were suspended. The RCC (Revolutionary Command Council) was abolished in 1996, and the ruling National Congress Party took over leadership. After 1997, the structure of regional administration was replaced by the creation of 25 states. The executives, cabinets, and senior-level state officials are appointed by the president. Their limited budgets are determined by and dispensed from Khartoum, making the states economically dependent upon the central government.

In December 1999, a power struggle climaxed between President al-Bashir and then-Speaker of parliament Hassan al-Turabi. The government and parliament were suspended. A state of national emergency was declared by presidential decree. Parliament resumed again February, 2001, after the December 2000 presidential and parliamentary elections. The national emergency laws remained in effect. This was a time when an interim government was preparing to take over in accordance with the Naivasha agreement and the Machokos Accord.

The Government of National Unity (GNU) - the National Congress Party (NCP) and Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) formed a power-sharing government under the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA); the NCP, which came to power by military coup in 1989, is the majority partner; the agreement stipulated national elections for the 2008 - 2009 timeframe.

A constitution was established on April 12, 1973 and suspended following the coup of April 6, 1985. An interim constitution established on October 10, 1985 was suspended following a coup on June 30, 1989. A new constitution was implemented on June 30, 1998 and partially suspended December 12, 1999 by President Umar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir. Under the CPA, an Interim National Constitution was ratified July 5, 2005 which granted Southern Sudan autonomy for six years, to be followed by a referendum about independence in 2011. This referendum was held on January 9, 2011; the result showed 98.9 percent in favor of secession. The southern region became independent on July 9, 2011, with the name of South Sudan.

On October 14th, 2006 a peace treaty was signed by the eastern Sudanese and the Sudanese Government headed by President Al-Bashir. He stated that it was "Africans solving African's problems without foreign help." Efforts are being made to solve the crisis in Darfur and other regions in Sudan. President George W. Bush, for example, put a sanction on areas where top leaders are suspected in the killing of innocent people.

Autonomy, separation, and conflicts

South Sudan formally became independent from Sudan on July 9, 2011 following the referendum held in January 2011.

Darfur is a region of three western states affected by the Darfur conflict. In August 2019 a Draft Constitutional Declaration was signed by military and civilian representatives during the Sudanese Revolution, requiring that a peace process leading to a peace agreement be made in Darfur and other regions of armed conflict in Sudan. A comprehensive peace agreement was signed on August 31, 2020 between the Sudanese authorities and several rebel factions to end armed hostilities.

In April 2023 – as an internationally-brokered plan for a transition to civilian rule was discussed – power struggles grew between army commander (and de facto national leader) Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, and his deputy, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, head of the heavily-armed paramilitary Rapid Support Forces & Rapid Strike Force ("RSF"), formed from the Janjaweed militia. On April 15 2023, their conflict erupted into intensely violent open battles in the streets of Khartoum between the army and the RSF – with troops, tanks and planes. By the third day, 400 people had been reported killed and at least 3,500 injured. Among the dead were three workers from the World Food Program, triggering a suspension of the organization's work in Sudan, despite ongoing hunger afflicting much of the country. A brief ceasefire (3–4 hours) was declared to permit evacuation of wounded,

The outbreak of violence has led foreign governments to evacuate its nationals. Efforts at extraction were hampered by the fighting within the capital Khartoum, particularly in and around the airport. This forced evacuations to be undertaken by road via Port Sudan on the Red Sea, which lies about 650 km (400 miles) northeast of Khartoum. from where they were airlifted or ferried directly to their home countries or to third ones. Major transit hubs used during the evacuation include the port of Jeddah in Saudi Arabia and Djibouti, which hosts military bases of the United States, China, Japan, France, and other European countries.[8]

Foreign relations

The foreign relations of Sudan are generally in line with the Muslim Arab world, but are also based on Sudan's economic ties with the People's Republic of China and Western Europe.

Sudan's administrative boundary with Kenya does not coincide with international boundary, and Egypt asserts its claim to the "Hala'ib Triangle," a barren area of 20,580 km² under partial Sudanese administration that is defined by an administrative boundary which supersedes the treaty boundary of 1899.

Solidarity with other Arab countries has been a feature of Sudan’s foreign policy. When the Arab-Israeli war began in June 1967, Sudan declared war on Israel. However, in the early 1970s, Sudan gradually shifted its stance and was supportive of the Camp David Accords.

Relations between Sudan and Libya deteriorated in the early 1970s and reached a low in October 1981, when Libya began a policy of crossborder raids into western Sudan. After the 1989 coup d'état, the military government resumed diplomatic relations with Libya, as part of a policy of improving relations with neighboring Arab states. In early 1990, Libya and the Sudan announced that they would seek “unity.” This unity was never implemented.

During the 1990s, Sudan sought to steer a nonaligned course, courting Western aid and seeking rapprochement with Arab states, while maintaining cooperative ties with Libya, Syria, North Korea, Iran, and Iraq. Sudan’s support for regional insurgencies such as Egyptian Islamic Jihad, Eritrean Islamic Jihad, Ethiopian Islamic Jihad, Palestinian Islamic Jihad, Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Lord's Resistance Army generated great concern about their contribution to regional instability. Allegations of the government’s complicity in the assassination attempt against the Egyptian president in Ethiopia in 1995 led to UN Security Council sanctions against the Sudan. By the late 1990s, Sudan experienced strained or broken diplomatic relations with most of its nine neighboring countries.

On November 3, 1997, the U.S. government imposed a trade embargo against Sudan and a total asset freeze against the Government of Sudan under Executive Order 13067. The U.S. believed the Government of Sudan gave support to international terrorism, destabilized neighboring governments, and permitted human rights violations, creating an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security and foreign policy of the United States.

Since 2000, Sudan has actively sought regional rapprochement that has rehabilitated most of these regional relations. Joint Ministerial Councils have been set up between Sudan and Ethiopia and Sudan and Egypt. Relations with Uganda are generally good in spite of the death of former Vice-President Dr John Garang de Mabior while on a Ugandan Presidential Helicopter.

On December 23, 2005 Chad, Sudan's neighbor to the west, declared a 'state of belligerency' with Sudan and accused the country of being the "common enemy of the nation (Chad)." This happened after the December 18 attack on Adre, which left about 100 people dead. A statement issued by Chadian government on December 23, accused Sudanese militias of making daily incursions into Chad, stealing cattle, killing innocent people and burning villages on the Chadian border. The statement went on to call for Chadians to form a patriotic front against Sudan. [9]

Sudan is one of the states that recognize Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara.

Economy

Sudan has turned around a struggling economy with sound economic policies and infrastructure investments, but it still faces formidable economic problems. Since 1997 Sudan has been implementing the macroeconomic reforms recommended by the IMF. Currently oil is Sudan's main export, and the production has been increasing dramatically. In 1999, Sudan began exporting crude oil and in the last quarter of 1999 recorded its first trade surplus. Increased oil production revived light industry and expanded export processing zones. These gains, along with improvements to monetary policy, stabilized the exchange rate.

Agriculture production remains Sudan's most important sector. Still, most farms remain rain-fed and susceptible to drought. Chronic instability — including the long-standing civil war between the Muslim north and the Christian/Animist south, adverse weather, and weak world agricultural prices — ensure that much of the population will remain at or below the poverty line for years.

Demographics

In Sudan’s 2008 census, the population was calculated at over 30 million. No comprehensive census has been carried out since that time. Estimates put the population to be close to 50 million. The population of metropolitan Khartoum (including Khartoum, Omdurman, and Khartoum North) is growing rapidly and is estimated at between five and six million, including around two million displaced persons from the southern war zone as well as western and eastern drought-affected areas.

Sudan has two distinct major cultures—Arabs with Nubian (Kushite) roots and non-Arab Black Africans—with hundreds of ethnic and tribal divisions and language groups, which makes effective collaboration among them a major problem.

The northern states cover most of the Sudan and include most of the urban centers. Most of the twenty-two million Sudanese who live in this region are Arabic-speaking Muslims, though the majority also use a traditional non-Arabic mother tongue — e.g., Nubian, Beja, Fur, Nuban, Ingessana, etc. Among these are several distinct tribal groups: the Kababish of northern Kordofan, a camel-raising people; the Dongolese, the Ga’alin, Rubatab, Manasir and Shaiqiyah of the tribes settling along the rivers; the seminomadic Baggara of Kurdufan and Darfur; the Beja in the Red Sea area and Nubians of the northern Nile areas, some of whom have been resettled on the Atbara River. Shokrya in the Butana land, Bataheen bordering the Ga’alin and Shorya in the south west of Butana, Rufaa, Halaween and many other tribes are in the Gazeera region and on the banks of the Blue Nile and the Dindir region. The Nuba of southern Kurdufan and Fur are in the western reaches of the country.

Official languages

According to the Constitution of 2005, official languages are the Arabic and English languages. Article 8 of the Constitution states:

1) All indigenous languages of the Sudan are national languages and shall be respected, developed and promoted.

2) Arabic is a widely spoken national language in the Sudan.

3) Arabic, as a major language at the national level and English shall be the official working languages of the national government and the languages of instruction for higher education.

4) In addition to Arabic and English, the legislature of any sub-national level of government may adopt any other national language as an additional official working language at its level.

5) There shall be no discrimination against the use of either Arabic or English at any level of government or stage of education.

Religion and Culture

Sudanese culture melds the behaviors, practices, and beliefs of about 578 tribes, communicating in 145 different languages, in a region microcosmic of Africa, with geographic extremes varying from sandy desert to tropical forest.

Ethnicity

In 1999, Sudan was one of the most ethnically and linguistically diverse countries in the world. It had nearly 600 ethnic groups speaking over 400 languages/dialects.

During the 1980s and 1990s some of Sudan's smaller ethnic and linguistic groups disappeared. Migration played a part, as migrants often forget their native tongue when they move to an area dominated by another language. Some linguistic groups were absorbed by accommodation, others by conflict.

Arabic was the lingua franca despite the use of English by many of the elite. Many Sudanese are multilingual.

Religion

The majority of Sudanese are Muslim, primarily Sunni, with smaller numbers of Christians and adherents of traditional religions. In September 2020, Sudan constitutionally became a secular state after Sudan's transitional government agreed to separate religion from the state, ending 30 years of Islamic rule and Islam as the official state religion in the North African nation.

In the early 1990s, the largest single category among the Muslim peoples of Sudan consisted of those speaking some form of Arabic. Excluded were a small number of Arabic speakers originating in Egypt and professing Coptic Christianity. In 1983 the people identified as Arabs constituted nearly 40 percent of the total Sudanese population and nearly 55 percent of the population of the northern provinces. In some of these provinces (Al Khartum, Ash Shamali, Al Awsat), they were overwhelmingly dominant. In others (Kurdufan, Darfur), they were less so but made up a majority. By 1990 Ash Sharqi State was probably largely Arab. It should be emphasized, however, that the acquisition of Arabic as a second language did not necessarily lead to the assumption of Arab identity.

In the early 1990s, the Nubians were the second most significant Muslim group in Sudan, their homeland being the Nile River valley in far northern Sudan and southern Egypt. Other, much smaller groups speaking a related language and claiming a link with the Nile Nubians have been given local names, such as the Birqid and the Meidab in Darfur State. Almost all Nile Nubians speak Arabic as a second language.

Christianity

Christianity was most prevalent among the peoples of Al Istiwai State—the Madi, Moru, Azande, and Bari. The major churches in the Sudan were the Catholic and the Anglican. Southern communities might include a few Christians, but the rituals and world view of the area were not in general those of traditional Western Christianity. The few communities that had formed around mission stations had disappeared with the dissolution of the missions in 1964. The indigenous Christian churches in Sudan, with external support, continued their mission.

Indigenous religions

Each indigenous religion is unique to a specific ethnic group or part of a group, although several groups may share elements of belief and ritual because of common ancestry or mutual influence. The group serves as the congregation, and an individual usually belongs to that faith by virtue of membership in the group. Believing and acting in a religious mode is part of daily life and is linked to the social, political, and economic actions and relationships of the group. The beliefs and practices of indigenous religions in Sudan are not systematized, in that the people do not generally attempt to put together in coherent fashion the doctrines they hold and the rituals they practice.

Music

Sudan has a rich and unique musical culture that has been through chronic instability and repression during the modern history of Sudan. Beginning with the imposition of strict sharia law in 1989, many of the country's most prominent poets, such as Mahjoub Sharif, were imprisoned while others, like Mohammed el Amin and Mohammed Wardi fled temporarily to Cairo. Traditional music suffered too, with traditional Zar ceremonies being interrupted and drums confiscated. At the same time, however, the European militaries contributed to the development of Sudanese music by introducing new instruments and styles; military bands, especially the Scottish bagpipes, were renowned, and set traditional music to military march music. The march March Shulkawi No 1, is an example, set to the sounds of the Shilluk.

The Nuba, on the front lines between the north and the south of Sudan, have retained a vibrant folk tradition. The musical harvest festival Kambala is still a major part of Nuba culture. The Sudan People's Liberation Army (SPLA) include a group called the Black Stars, a unit dedicated to "cultural advocacy and performance."

Sport

Several Sudanese born basketball players have played in the American National Basketball Association. These include Deng Gai, Luol Deng and Manute Bol.

The Khartoum state league is considered to be the oldest soccer league in the whole of Africa as it began in the late 1920s. The Sudan Football Association started in 1954. The Sudan national football team, nicknamed Sokoor Al-Jediane is the national team of Sudan and is controlled by the Sudan Soccer Association. It is one of only a few countries to have played since the inaugural African Nations Cup in 1957. Todd Matthews-Jouda switched nationalities from American to Sudanese in September 2003 and competed at the 2004 Summer Olympics.

Education

The public and private education systems inherited by the government after independence were designed more to provide civil servants and professionals to serve the colonial administration than to educate the Sudanese.

Since World War II the demand for education has exceeded Sudan's education resources. At independence in 1956, education accounted for only 15.5 percent of the Sudanese budget. By the late 1970s, the government's education system had been largely reorganized. There were some preprimary schools, mainly in urban areas. The basic system consisted of a six-year curriculum in primary schools and three-year curriculum in junior secondary schools. From that point, qualified students could go on to one of three kinds of schools: the three-year upper secondary, which prepared students for higher education; commercial and agricultural technical schools; and teacher- training secondary schools designed to prepare primary-school teachers.

The proliferation of upper-level technical schools has not dealt with what most experts saw as Sudan's basic education problem: providing a primary education to as many Sudanese children as possible. Establishing more primary schools was, in this view, more important that achieving equity in the distribution of secondary schools. Even more important was the development of a primary-school curriculum that was geared to Sudanese experience and took into account that most of those who completed six years of schooling did not go further.

1990 reforms

The revolutionary government of General Bashir announced sweeping reforms in Sudanese education in September 1990. In consultation with leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood and Islamic teachers and administrators, who were the strongest supporters of his regime, Bashir proclaimed a new philosophy of education. He allocated £Sd400 million for the academic year 1990-91 to carry out these reforms and promised to double the sum if the current education system could be changed to meet the needs of Sudan.

The new education philosophy was to provide a frame of reference for the reforms. Education was to be based on the permanence of human nature, religious values, and physical nature. This was to be accomplished by a Muslim curriculum, which in all schools, colleges, and universities would consist of two parts: an obligatory and an optional course of study. All the essential elements of the obligatory course would be drawn from the Quran and the recognized books of the hadith. The optional course of study would permit the student to select certain specializations according to individual aptitudes and inclinations. Membership in the Popular Defence Forces, a paramilitary body allied to the National Islamic Front, became a requirement for university admission.

Higher education

The oldest university is the University of Khartoum, which was established as a university in 1956. Since that time, ten other universities have opened in the Sudan. These include:

- Academy of Medical Sciences

- Ahfad University for Women

- Bayan Science and Technology College

- Computerman College

- Omdurman Ahlia University

- Omdurman Islamic University

- University of Gezira

- University of Juba

- Mycetoma Research Centre

- Sudan University of Science and Technology

Notes

- ↑ CIA, Sudan World Factbook. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- ↑ Discontent over Sudan census News24, May 21, 2009. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Sudan International Monetary Fund.

- ↑ Sudan - GINI index (World Bank estimate) IndexMundi. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- ↑ H.A. R. Musnad and M.A. el-Rasheed, Soil conservation and land reclamation in the Sudan Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- ↑ Sudan Environment Encyclopedia of the Nations. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- ↑ Sudan deal to end Abyei clashes BBC News, January 14, 2011. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- ↑ Sankalp Gurjar, How the crisis in Sudan accentuated the strategic importance of Djibouti Observer Research Foundation (ORF), April 25, 2023. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- ↑ Stephanie Hancock, Chad in 'state of war' with Sudan BBC News, December 23, 2005. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Clammer, Paul. Sudan: The Bradt Travel Guide. Chalfont St. Peter, Bucks, England: Bradt Travel Guides, 2005. ISBN 1841621145

- Meyer, Gabriel, and James Nicholls. War And Faith In Sudan. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2005. ISBN 0802829333

- Rayah, Mubarak B. Sudan Civilization. Democratic Republic of the Sudan, Ministry of Culture and Information, 1978. ASIN B000IAPNWM

- Prunier,Gerald. Darfur: The Ambiguous Genocide. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005. ISBN 0801444500

- This article contains material from the Library of Congress Country Studies, which are United States government publications in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved April 30, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Sudan history

- Geography_of_Sudan history

- Foreign_relations_of_Sudan history

- Culture_of_Sudan history

- Education_in_Sudan history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.