Bagpipes are a class of musical instrument that uses a reed, in addition to air provided by the player, to create a distinctive, pleasant, and melodic sound. Bagpipes have been around for many hundreds, if not thousands, of years and some trace the origin of the instrument back to the snake charming pipes of the Middle East. Bagpipes, although classified as an aerophone (using air to produce sound) and a reedpipe (using a reed), are difficult to harmonize with other instruments; as a result, bagpipes are often played in small groups or bands made up entirely of pipes, or pipes and drums. As a musical instrument, bagpipes are unique. Their construction is complex, and yet, they have been a favorite instrument among the common people of Europe for quite some time.

Perhaps because of the ancient nature of their sound, the bagpipes present a lyric, almost magical quality in the tone they create. They are an honored instrument and their power is taken seriously. The human ability to express creative thoughts, and to express emotions is exemplified in the instrument.

Overview

A bagpipe minimally consists on an air supply, a bag, a chanter, and usually a drone. Some bagpipes also have additional drones (and sometimes chanters) in various combinations, although the most common number is three: two tenors and a bass.[1] These drones are held in place in stocksâconnectors with which the various pipes are attached to the bag. The chanter is the melody pipe, and everything is attached to the bag, made either of synthetic materials or more traditional leather.

Bagpipes are classified as an aerophone, or an instrument needing air in order to make sound. Further, they are branched with reedpipes, which all function via vibration of the reed.[2]

Air supply

The most common method of supplying air to the bag is by blowing into a blowpipe, or blowstick. In some pipes the player must cover the tip of the blowpipe with his tongue while inhaling, but modern blowpipes are usually fitted with a non-return valve, which eliminates this need. The air supply is provided to the bag which then supplies its air to the drones and chanter. The piper, thus, is only indirectly supplying air to the pipes.[1]

An innovation, dating from the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries, is the use of a bellows to supply air. In these pipes, (sometimes called coldpipes) air is not heated or moistened by the player's breathing, so bellows-driven bagpipes can use more refined and/or delicate reeds. The most famous of these pipes are the Irish uilleann pipes and the Northumbrian smallpipes.

The possibility of using an artificial air supply, such as an air compressor, is occasionally discussed by pipers, and although experiments have been made in this direction, widespread adoption seems unlikely.

Bag

The bag is an airtight (or nearly airtight) reservoir which can hold air and regulate its flow while the player breathes or pumps with a bellows, enabling the player to maintain continuous sound for some time. Materials used for bags vary widely, but the most common traditional sources are the skins of local animals such as goats, sheep, and cows. More recently, bags made of synthetic materials including Gore-Tex have become common.

Bags cut from larger materials are usually saddle-stitched with an extra strip folded over the seam and stitched (for skin bags) or glued (for synthetic bags) to minimize leaks. Holes are cut to accommodate the stocks. In the case of bags made from largely-intact animal skins, the stocks are typically tied into the points where limbs and the head joined the body of the living animal, a construction technique common in Central and Eastern Europe.

Chanter

The chanter is the melody pipe and can be played by one or two hands. A chanter can be bored internally so that the inside walls are parallel for its full length, or it can be bored in the shape of a cone. Additionally, the reed can be a single or a double reed. Single-reeded chanters must be parallel-bored; however, both conical and parallel-bored chanters operate with double reeds, making double reeds by far the most common.

The chanter is usually open-ended; thus, there is no easy way for the player to stop the pipe from sounding. This means that most bagpipes share a legato (smooth and slurred) sound where there are no rests in the music. Primarily because of this inability to stop playing, grace notes (which vary between types of bagpipe) are used to break up notes and to create the illusion of articulation and accents. Because of their importance, these embellishments (or ornaments) are often highly technical systems specific to each bagpipe, requiring much study to master.

A few bagpipes (the musette de cour, the uilleann pipes, and the Northumbrian smallpipe) have closed ends or the player wears a thick leather leg strap, known as a "Piper's Apron," where the end of the chanter can be pressed, so that when the player covers all the holes (known as "closing the chanter"), the instrument becomes silent. This allows for staccato playing on these instruments. However, complex embellishment systems often exist even in cases where the chanter can be silenced. Momentarily silencing the open end of the Uilleann pipe chanter on the "Apron," alongside an increase in pressure on the bag, allows the melody pipe to sound the next register. This is not done on other forms of bagpipes.

Although the majority of chanters are unkeyed, some make extensive use of keys to extend the range and the number of accidentals the chanter can play. It is possible to produce chanters with two bores and two holes for each note. These "double chanters" have a full, loud sound, comparable to the "wet" sound produced by an accordion. One ancient form of twin bore, single reed pipe is the "Scottish Stock and Horn" spoken of by Robert Burns.

An unusual kind of chanter is the regulator of the uilleann pipes. This chanter is found in addition to the main melody chanter and plays a limited number of notes, operated by the ends of the palms pressing down the keys. It is fitted in the stock for the drones and laid across the knees, allowing the player to produce a limited, but effective, chordal accompaniment.

A final variant of the chanter is the two-piped chanter (confusingly also usually called a "double chanter"). Two separate chanters are designed to be played, one with each hand. When they are played, one chanter may provide a drone accompaniment to the other, or the two chanters may play in a harmony of thirds and sixths, or the two chanters may be played in unison (as in most Arabic bagpipes).

Because of the accompanying drone(s), the lack of modulation in bagpipe melody, and stable timbre of the reed sound, in many bagpipe traditions, the tones of the chanter are appropriately tuned using just intonation (where two notes are members of the same harmonic series).

Drone

Most bagpipes have at least one drone. A drone is most commonly a cylindrical tube with a single reed, although drones with double reeds do exist. The drone is generally designed in two or more parts, with a sliding joint ("bridle") so that the pitch of the drone can be manipulated. Drones are traditionally made of wood, often a local hardwood, although modern instruments are often made from tropical hardwoods such as rosewood, ebony, or African Blackwood. Some modern variants of the pipes have brass or plastic drones.

Depending on the type of pipe, the drones may lay over the shoulder, across the arm opposite the bag, or may run parallel to the chanter. Some drones have a tuning screw, which effectively alters the length of the drone by opening a hole, allowing the drone to be tuned to two or more distinct pitches. The tuning screw may also shut off the drone altogether. In general, where there is one drone it is pitched two octaves below the tonic of the chanter, and further additions often add the octave below and then a drone consonant with the fifth of the chanter. This is, however, a very approximate rule of thumb. In the Uilleann pipes, there are three drones (which can be turned off by using a switch).

History

While the bagpipes are often agreed to be an old, if not ancient, instrument, their lineage is a difficult one to decipher. This is the case for many reasons, but probably most likely because the instruments themselves were made of entirely or most entirely of organic materials. They were not long-lasting, and thus, did not preserve well at all. Poor storage conditions exacerbated the matter; nearly all ancient bagpipes have become victims of time and their exact age is difficult to pinpoint.[3]

Ancient origins

Some argue that the bagpipe has its origin in antiquity, and could be found throughout Asia, in North Africa, and across Europe.[4] In fact, a type of primitive bagpipe is mentioned in the Old Testament. Ancient Greek writings dated to the fifth century B.C.E. also mention bagpipes. Suetonius described the Roman Emporer Nero as a player of the tibia utricularis.[5] In relation to this, Dio Chrysostom, who also flourished in the first century, wrote about a contemporary sovereign (possibly Nero) who could play a pipe ("aulein") with his mouth as well as with his "armpit."[6] From this account, some believe that the tibia utricularis was a bagpipe. Yet, it is difficult to say anything concrete about the ancient origins of the bagpipes. Some theories also argue that ancient Celts brought the bagpipes with them as they migrated across Europe.[7]

Spread and development in Europe

Many argue that the bagpipes can find their origins in the Middle East, as they bear a resemblance to the single reeded "snake charming" flute.[1] As various peoples from the Middle East migrated through Europe, they brought the bagpipes and reeded flutes with them. The bagpipes then became popular in Europe, especially with common people, in general becoming a folk instrument.

As bagpipes became entrenched in European culture, their presence gets easier to track. Evidence of the bagpipe in Ireland occurs in 1581, with the publication of John Derrick's The Image of Irelande which clearly depicts a bagpiper falling in battle in one of the woodblock prints. Derrick's illustrations are considered to be reasonably faithful depictions of the attire and equipment of the English and Irish population of the sixteenth century.[8]

Although in the present day, bagpipers are popularly associated with Scotland, it was not until 1760 that the first serious study of the Scottish Highland bagpipe and its music was attempted, in Joseph MacDonald's Compleat Theory. Further south, a manuscript from the 1730s by a William Dixon from Northumberland contains music which fits the Border pipes, a nine-note bellows-blown bagpipe whose chanter is similar to that of the modern Great Highland Bagpipe. However the music in Dixon's manuscript varied greatly from modern Highland bagpipe tunes, consisting mostly of common dance tunes of the time.

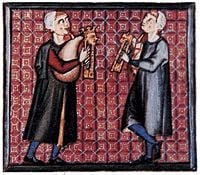

Due to the difficulty in preserving them, actual physical examples of bagpipes from earlier than the eighteenth century are extremely rare; however, a substantial number of paintings, carvings, engravings, manuscript illuminations, and other illustrations of bagpipes survive, from as early as the thirteenth century. They make it clear that bagpipes varied hugely throughout Europe, and even within individual regions. Many examples of early folk bagpipes in continental Europe can be found in the paintings of Brueghel, Teniers, Jordaens, and Durer.[9]

As Western classical music developed, both in terms of musical sophistication and instrumental technology, bagpipes in many regions fell out of favor due to their limited range and function. This triggered a long, slow decline in popularity which continued into the twentieth century in many areas.

Extensive and documented collections of traditional bagpipes can be found in the Musical Instrument section of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, and at the International Bagpipe Museum in GijĂłn, Spain, and Pitt Rivers Museum in England.

In Scotland

There is perhaps no culture more associated with bagpipes than that of the Highland Scottish. The particular style of bagpipe associated with the Scottish are known as the Great Highland Bagpipes, and have the distinction of being the only musical instrument to ever be labeled as a "weapon." The general mythology holds that at the Battle of Culloden, in 1748, the pipes stirred Scottish troops to arms, allied with the French Jacobites, against the British. And while the battle ended in massacre for the Scots, Irish, and Jacobites, the bagpipes as instigators of insurrection were taken seriously. The piper who had wielded them at the battle was executed.

Later, however, the British military found that kilts and bagpipes were great motivators for their Scottish regiments. To facilitate this, a kind of artificial Highland culture was created and introduced into Scottish history and mythology, partially under the pretense of "saving" an endangered art form. Thus, the military, standardized piping flourished, at the expense of the more fluid musical forms of pipe music that had also previously been popular. This has added to the mythology of bagpipes as being primarily, even uniquely, Scottish. But this is simply not the case.[1]

Recent history

During the expansion of the British Empire, spearheaded by British military forces which included Highland regiments, the Scottish Great Highland Bagpipe was diffused and became well-known world-wide. This surge in popularity was boosted by large numbers of pipers trained for military service in the two World Wars. This surge coincided with a decline in the popularity of many traditional forms of bagpipe music throughout Europe, as bagpipes began to be displaced by instruments from the classical tradition and later by gramophone and radio. Taking up the model of the British military, a number of police forces in Scotland, Canada, Australia, Hong Kong, and the United States also formed pipe bands. The Tayside Police Pipe band, still in existence, was founded in 1905. In the United Kingdom and Commonwealth Nations such as Canada and New Zealand, the bagpipe is commonly used in the military and is often played in formal ceremonies. A number of countries have also taken the Highland bagpipe into use in their ceremonial military forces, including but not restricted to Uganda, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Oman, effectively spreading official military use to Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

In more recent years, revivals of native folk music and dance have helped many instruments that were on the brink of extinction to attract new interest, and many types of bagpipes have benefited from this trend, with a resurge in popularity. In Brittany, the concept of the pipe band was appropriated, the Great Highland Bagpipe was imported and the bagad was created, a showcase ensemble for Breton folk music. The pipe band idiom has also been adopted and applied to the Spanish gaita as well.

Bagpipes have often been used in various films depicting moments from Scottish and Irish history. Riverdance served to make the Uilleann pipes more commonly known. There have also seen recent experimentation with various forms of rock (usually progressive rock), such as in the band The Dropkick Murphys, and heavy metal bands have used bagpipes as guest instruments on their albums.

By the late twentieth century, various models of electronic bagpipes had been invented. The first custom-built MIDI bagpipes were developed by JosĂŠ Ăngel Hevia Velasco (generally known simply as Hevia).[10] Some models allow the player to select the sound of several different bagpipes as well as switch keys. As yet, they are not widely used due to technical limitations, but they have found a useful niche as a practice instrument.

Modern use

Types of bagpipes

Dozens of types of bagpipes today are widely spread across Europe and the Middle East, as well as through much of the former British Empire. The term "bagpipe" has become nearly synonymous with its best-known form, the Great Highland Bagpipe, overshadowing the great number and variety of traditional forms of bagpipe. After a decline in popularity over the last few centuries, in recent years many of these other kinds of pipes have seen a resurgence as musicians with interest in world music traditions have sought them out; for example, the Irish piping tradition, which by the mid twentieth century had declined to a handful of master players, is today alive, well, and flourishing in a situation similar to that of the Asturian gaita, the Galician gaita, the Aragonese Gaita de boto, Northumbrian smallpipes, the Breton Biniou, the Balkan Gaida, the Turkish Tulum, the Scottish smallpipes and Pastoral pipes, as well as other varieties.

Traditionally, one of the main purposes of the bagpipe in most traditions was to provide music for dancing. In most countries, this decline in popularity has corresponded to the growth of professional dance bands, recordings, along with the decline of traditional dance. In turn, this has led to many types of pipes being used for instrumental performances, rather than as accompaniment for dancing, and indeed much modern music played on bagpipes, while based on traditional dance music originally played on bagpipes is no longer suitable for use as dance music.

Royal pipers

Since 1843, the British Sovereign has retained an official piper, bearing the title "Personal Piper to the Sovereign."[11] Queen Victoria was the first monarch to have a piper, after hearing bagpipe music on a trip to Scotland in 1842. It has since been tradition that a serving soldier and experienced army Pipe Major is taken on secondment to Buckingham Palace. The Piper is a member of the Royal Household whose principal duty is to play every weekday at 9am for about 15 minutes under The Queen's window when she is in residence at Buckingham Palace, Windsor Castle, the Palace of Holyroodhouse, or Balmoral Castle. He is also responsible for the coordination of the twelve Army pipers who play around the table after State Banquets.

Usage in non-traditional music

Since the 1960s, bagpipes have also made appearances in other forms of music, including rock, jazz, hip-hop, and classical music. For example, they have appeared on Paul McCartney's "Mull of Kintyre," AC/DC's "It's A Long Way To The Top," Korn's "Shoots and Ladders," and Peter Maxwell Davies's composition Orkney Wedding, With Sunrise. The American musician Rufus Harley was the first to use the bagpipes as a primary instrument in jazz.

The bagpipes continue to find a place in modern music, and continue to be popular with innovative artists and musicians.

Further reading

- Baines, Anthony. Bagpipes. Occasional papers on technology, 9. Oxford: Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, 1995. ISBN 9780902793101.

- Baines, Anthony. Woodwind instruments and their history. New York: Dover, 1991. ISBN 9780486268859.

- Campbell, Jeannie. Highland bagpipe makers. [S.l.]: College Of Piping, 2001. ISBN 9781899780020.

- Cannon, Roderick D. The Highland bagpipe and its music. Edinburgh: Donald, 1988. ISBN 9780859761536.

- Cheape, Hugh. The book of the bagpipe. Lincolnwood, Ill: Contemporary Books, 2000. ISBN 9780809296804.

- Collinson, Francis M. The bagpipe: the history of a musical instrument. London: Routledge & K. Paul, 1975. ISBN 9780710079138.

- Dixon, William, and Matt Seattle. The master piper: nine notes that shook the world : a border bagpipe repertoire. Peebles: Dragonfly Music, 2002. ISBN 9781872277332.

- Donaldson, William. The Highland pipe and Scottish society, 1750-1950. East Linton: Tuckwell, 1999. ISBN 9781862320758.

- Malcolm, C. A. The piper in peace and war. London: Hardwicke, 1993. ISBN 9780952158004.

- Pipes & Drums of the Scots Guards (Great Britain). Scots Guards: standard settings of pipe music. London: Paterson's Pub, 2000. ISBN 9780853609537.

- Vallverdu, Jordi. Mètode per a Sac de Gemecs (Catalan Bagpipe Tutor). CAT: Barcelona, 2008.

See also

- Musical instruments

- Folk Music

- History of music

Notes

- â 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Virginia A. Smith, About bagpipes. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- â Vermont University, Musical Instrument Classifications.

- â Oliver Seeler, History of Bagpipes, hotpipes.com, Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- â Anthony Kane, The Bagpipe, Article Alley, November 27, 2005, Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- â Suetonius, "Life of Nero", The Lives of the Caesars, 54, University of Chicago, Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- â Dio Chrysostom, "The Seventy-first Discourse," 71.9, Discourses, University of Chicago, Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- â Highland net, Bagpipes. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- â John Derrick, The image of Irelande: with a discoverie of wood karne (London: Daie, 1581.) The Image of Irelande online. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- â Robert Worrall, The Great Highland Bagpipes, Northport Bagpipes.

- â Susana Roza-Vigil, Galicia, CNN.com, November 5, 1999, Retrieved August 12, 2008.

- â The British Monarchy Website, The Queen's Piper. Retrieved August 12, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bailie, S.H. Piping and Drumming, an Integrated Approach. Belfast: Northern Ireland Piping and Drumming School, 1988.

- Cannon, Roderick D. The Highland bagpipe and its music. Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2008. ISBN 978-1841586663.

- Royal Scottish Pipe Band Association. Structured learning: the R.S.P.B.A. complete guide to piping and drumming certification. Book 1, The elementary certificate. Glasgow: The Association, 1998. OCLC 222234561

External links

All links retrieved August 26, 2023.

- Bagpipe iconography - Paintings and images of the pipes.

- History of the Highland Bagpipe

- The Royal New Zealand Pipe Band Association

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.