Ireland

| Éire (Irish) Ireland[a] |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| Anthem: "Amhrán na bhFiann" "The Soldier's Song" |

||||

| Location of the Ireland (dark green) – on the European continent (light green dark grey) – in the European Union (light green) |

||||

| Capital (and largest city) | Dublin 53°20.65′N 6°16.05′W | |||

| Official languages | Irish English |

|||

| Ethnic groups (2022) | Irish 76.6%, Irish travelers 0.6%, other White 9.9%, Asian 3.3%, Black 1.5%, other (includes Arab, Roma, and persons of mixed backgrounds) 2%, unspecified 2.6%[1] | |||

| Demonym | Irish | |||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic | |||

| - | President | Michael D. Higgins | ||

| - | Taoiseach | Micheál Martin | ||

| - | Tánaiste | Simon Harris | ||

| Legislature | Oireachtas | |||

| - | Upper House | Seanad Éireann | ||

| - | Lower House | Dáil Éireann | ||

| Independence | from the United Kingdom | |||

| - | Declared | April 24, 1916 | ||

| - | Ratified | January 21, 1919 | ||

| - | Recognised | December 6, 1922 | ||

| - | Constitution | December 29, 1937 | ||

| - | Left the Commonwealth | April 18, 1949 | ||

| EU accession | January 1, 1973 | |||

| Area | ||||

| - | Total | 70,273 km² (120th) 27,133 sq mi |

||

| - | Water (%) | 2.00 | ||

| Population | ||||

| - | 2024 estimate | 5,287,105[2] (122nd) | ||

| - | 2022 census | 5,149,139[3] | ||

| - | Density | 71.3/km² (113th) 184.7/sq mi |

||

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate | |||

| - | Total | |||

| - | Per capita | |||

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate | |||

| - | Total | |||

| - | Per capita | |||

| Gini (2023) | 27.4[5] | |||

| Currency | Euro (€)[c] (EUR) |

|||

| Time zone | WET (UTC+0) | |||

| - | Summer (DST) | IST (WEST) (UTC+1) | ||

| Internet TLD | .ie[b] | |||

| Calling code | [[+353]] | |||

| a. ^ Article 4 of the Constitution of Ireland declares that the name of the state is Ireland; Section 2 of the Republic of Ireland Act 1948 declares that the description of the state is the Republic of Ireland.[6] b. ^ The .eu domain is also used, as it is shared with other European Union member states. c. ^ Prior to 2002, Ireland used the punt (Irish pound) as its circulated currency. The euro was introduced as an accounting currency in 1999. |

||||

The Republic of Ireland, often referred to as simply Ireland, is a country in north-western Europe occupying five-sixths of the island of Ireland. The remainder of the island is occupied by Northern Ireland, a constituent state of the United Kingdom. Besides Northern Ireland to its north, it is also bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the west and by the Irish Sea to the east.

More than 40 million Americans, and millions of others around the world, call the Emerald Isle their ancestral home, due in large part to mass exodus during the Irish potato famine of the 1800s.

Its rugged western coast, majestic scenery and rolling green hills allow one to believe in the abundance of folklore that had its birthplace here. A rich heritage of culture and tradition is part of the Irish character and reputation.

Geography

The island of Ireland extends over 32,556 square miles, (84,421 square kilometers) of which 83 percent belong to the republic (70,280 km²;) and the remainder constituting Northern Ireland. The republic is slightly larger than the U.S. state of West Virginia.

It is bound to the west by the Atlantic Ocean, to the northeast by the North Channel, to the east is the Irish Sea which reconnects to the ocean via the southwest with St George's Channel and the Celtic Sea.

The ocean is responsible for the rugged western coastline, along which are many islands, peninsulas, and headlands. The main geographical features of Ireland are low central plains surrounded by a ring of coastal mountains. The highest peak is Carrauntoohil (Irish language: Corrán Tuathail), which is at 3406 feet (1038 meters).

The local temperate climate is modified by the North Atlantic Current and is relatively mild. Summer temperatures commonly reach 84ºF (29ºC), and freezes occur only occasionally in winter, with temperatures below 21ºF ( -6ºC) being uncommon. Precipitation is common, with up to 275 days with rain in some parts of the country.

There are a number of sizable lakes along Ireland's rivers, with Lough Neagh in Northern Ireland the largest. The island is bisected by the River Shannon, which at 161 miles (259km) with a 70 mile (113km) estuary, is the longest river in Ireland, and which flows south from County Cavan in the north to meet the Atlantic just south of Limerick. The center of the country is part of the River Shannon watershed, containing large areas of bogland, used for peat extraction and production.

Ireland has fewer animal and plant species than either Britain or mainland Europe because it became an island shortly after the end of the last Ice Age, about 8000 years ago. Many different habitat types are found in Ireland, including farmland, open woodland, temperate forests, conifer plantations, peat bogs, and various coastal habitats.

Forest of oak, ash, wych elm, birch, and yew was once the natural dominant vegetation, but centuries of farming have reduced it to five percent of the total area. Pine was dominant on poorer soils, with rowan and birch. Beech and lime thrive when introduced. Remnants of native forest can be found scattered around the country, in particular in the Killarney National Park.

Only 26 land mammal species are native to Ireland. Some species, such as the red fox, hedgehog, and badger are very common, whereas others, like the Irish hare, red deer and pine marten are less so. Aquatic wild-life - such as species of turtle, shark, whale, dolphin, and others - are common off the coast. About 400 species of birds have been recorded in Ireland. Many of these are migratory, including the swallow. Most of Ireland's bird species come from Iceland, Greenland, Africa among other territories. There are no snakes and only one reptile (the common lizard) is native to the country. Extinct species include the great Irish elk, the wolf, the great auk, and others. Some previously extinct birds - such as the golden eagle - have recently been reintroduced Ireland is noted for the Connemara pony, Irish wolfhound, Kerry blue terrier, while several types of cattle and sheep are recognized as distinct breeds.

Agriculture is the main factor determining land-use patterns in Ireland, leaving limited land to preserve natural habitats in particular for larger wild mammals with greater territorial requirements. With no top predator in Ireland, populations of animals that cannot be controlled by smaller predators (such as the fox) are controlled by annual culling, such as semi-wild populations of deer. Hedgerows, traditionally used for maintaining and demarcating land boundaries, act as a refuge for native wild flora. Their ecosystems stretch across the countryside and act as a network of connections to preserve remnants of the ecosystem that once covered the island.

Pollution from agricultural activities is one of the principal sources of environmental damage. "Runoff" of contaminants into streams, rivers and lakes impact the natural fresh-water ecosystems. Subsidies under the Common Agricultural Policy which supported these agricultural practices and contributed to land-use distortions are undergoing reforms The CAP still subsidizes some potentially destructive agricultural practices, however, the recent reforms have gradually decoupled subsidies from production levels and introduced environmental and other requirements.

The capital city is Dublin, population 1,046,000, located near the midpoint of Ireland's east coast, at the mouth of the River Liffey and at the center of the Dublin Region. Founded as a Viking settlement, the city has been Ireland's primary city since mediæval times. Today, it is an economic and cultural center for the island of Ireland, and has one of the fastest growing populations of any European capital city. Other cities include Cork 190,400 in the south, Limerick 90,800 in the mid-west, Galway 72,700 on the west coast, and Waterford 49,200 on the south east coast.

History

Stone age

Most of Ireland was covered with ice until about 9000 years ago, during the Ice Age. Sea-levels were lower then, and Ireland, as with its neighbor Britain, instead of being islands, were part of a greater continental Europe. Mesolithic middle stone age inhabitants arrived some time after 8000 B.C.E. About 4000 B.C.E., sheep, goats, cattle and cereals were imported from southwest continental Europe. At the Céide Fields in County Mayo, an extensive Neolithic field system - arguably the oldest in the world - has been preserved beneath a blanket of peat. Consisting of small fields separated from one another by dry-stone walls, the Céide Fields were farmed between 3500 and 3000 B.C.E. Wheat and barley were the principal crops in this high Neolithic culture, characterized by the appearance of pottery, polished stone tools, rectangular wooden houses and communal megalithic tombs. Four main types of megalithic tomb have been identified: Portal Tombs, Court Tombs, Passage Tombs (of Newgrange, Knowth, Dowth, Carrowkeel and Carrowmore), and Wedge Tombs. Some tombs are astronomically aligned. Newgrange is the oldest surviving building in the world.

Bronze age

About 400 megalithic wedge tombs associated with Beaker pottery dominate western Ireland, and mark the early Bronze Age, which began around 2500 B.C.E. in Ireland. Curiously, since there is no known source of tin (required to combine with copper to make the alloy bronze) in Ireland, the source is likely to be elsewhere. Similar tombs are common in Brittany, France. In the eastern areas of Ireland, a single-burial tradition dominates, with Beaker-style pottery similar to that in the lowland Rhine or farther north. Ireland had a flourishing metal industry, exporting bronze, copper, and gold objects to Britain and the Continent.

Celtic colonization

The main Celtic arrivals occurred in the Iron Age. The Celts, an Indo-European group who are thought to have originated in the second millennium B.C.E. in east-central Europe, are traditionally thought to have colonized Ireland in a series of waves between the eighth and first centuries B.C.E., with the Gaels, the last wave of Celts, conquering the island.

Ireland was never formally a part of the Roman Empire. The Romans referred to Ireland as Hibernia. Ptolemy in 100 C.E. recorded Ireland's geography and tribes.

The Five Fifths

Celtic society consisted of a number of independent petty kingdoms, or tuatha (clans), each with an elected king, which coalesced into five groups of tuatha, known as the Five Fifths (Cuíg Cuígí), about the beginning of the Christian era. These were Ulster, Meath, Leinster, Munster, and Connaught.

Each king was surrounded by an aristocracy, with clearly defined land and property rights, and whose main wealth was in cattle. Céilí, or clients supported greater landowners by tilling the soil and tending the cattle. Individual families were the basic units of society. The written judicial system was the Brehon Law, and it was administered by professional learned jurists who were known as the Brehons. Society was based on cattle rearing and agriculture. The principal crops were wheat, barley, oats, flax, and hay. Plows drawn by oxen were used to till the land. Sheep were bred for wool, and pigs for slaughter. Fishing, hunting, fowling, and trapping provided further food. Dwellings were built by the post-and-wattle technique, and some were situated within ring forts.

Each of the Five Fifths had its own king, although Ulster in the north was dominant at first. Niall Noigiallach (died c.450/455) laid the basis for the Uí Néill dynasty's hegemony over much of western, northern and central Ireland. By the time he died, hegemony had passed to his midland kingdom of Meath. In the sixth century, descendants of Niall, ruling at Tara in northern Leinster, claimed to be overkings of Ulster, Connaught, and Meath, and later, they claimed to be kings of all of Ireland.

Raids on England

From the mid-third century C.E., the Irish, who were at that time called Scoti rather than the older term Hiberni, carried out frequent raiding expeditions. Raids became incessant in the second half of the fourth century, when Roman power in Britain was beginning to crumble. The Irish settled along the west coast of Britain, Wales and Scotland.

Saints Palladius and Patrick

According to early medieval chronicles, in 431, Bishop Palladius arrived in Ireland on a mission from Pope Celestine to minister to the Irish "already believing in Christ." The same chronicles record that Saint Patrick, Ireland's patron saint, arrived in 432. There is continued debate over the missions of Palladius and Patrick, but the general consensus is that they both existed and that seventh century annalists may have mis-attributed some of their activities to each other. Palladius most likely went to Leinster, while Patrick is believed to have gone to Ulster, where he probably spent time in captivity as a young man.

Patrick is traditionally credited with preserving the tribal and social patterns of the Irish, codifying their laws and changing only those that conflicted with Christian practices. He is also credited with introducing the Roman alphabet, which enabled Irish monks to preserve parts of the extensive Celtic oral literature. The historicity of these claims remains the subject of debate. There were Christians in Ireland long before Patrick came, and pagans long after he died. However, it is undoubtedly true that Patrick played a crucial role in transforming Irish society.

The druid tradition collapsed in the face of the spread of Christianity. Irish Christian scholars excelled in the study of Latin and Greek learning and Christian theology in the monasteries that flourished, preserving Latin and Greek learning during the Early Middle Ages. The arts of manuscript illumination, metalworking, and sculpture flourished and produced such treasures as the Book of Kells, ornate jewelery, and the many carved stone crosses that dot the island.

English raid Ireland

In 684 C.E., an English expeditionary force sent by Northumbrian King Ecgfrith invaded Ireland in the summer of that year. The English forces managed to seize a number of captives and booty, but they apparently did not stay in Ireland for long.

Irish monasticism

Christian settlements in Ireland were loosely linked, usually under the auspices of a great saint. By the late sixth century, numerous Irishmen devoted themselves to an austere existence as monks, hermits, and as missionaries to pagan tribes in Scotland, the north of England, and in west-central Europe. A comprehensive monastic system developed in Ireland, partly influenced by Celtic monasteries in Britain, through the sixth and seventh centuries.

The monasteries became notable centers of learning. Christianity brought Latin, Irish scribes produced manuscripts written in the Insular style, which spread to Anglo-Saxon England and to Irish monasteries on the European continent. Initial letters were illuminated. The most famous Irish manuscript is the Book of Kells, a copy of the four Gospels probably dating from the late eighth century, while the earliest surviving illuminated manuscript is the Book of Durrow, probably made 100 years earlier.

Viking raiders

Vikings from Norway looted the island of Lambay, located off the Dublin in 795, the first recorded Viking raid on Ireland. Early Viking raids were small in scale and quick, but they interrupted the golden age of Christian Irish culture. Over the next 200 years, waves of Viking raiders plundered monasteries and towns throughout Ireland. By the early 840s, the Vikings began to establish settlements along the Irish coasts, at Limerick, Waterford, Wexford, Cork, and Arklow, and spent the winter months there.

In 852, the Vikings Ivar Beinlaus and Olaf the White landed in Dublin Bay and established a fortress, on which the city of Dublin stands. Olaf was the son of a Norwegian king and made himself the king of Dublin. Intermarriage led to the emergence of a group with mixed Irish and Norse ethnic background arose (the so-called Gall-Gaels, Gall then being the Irish word for "foreigners"—the Norse). The descendants of Ivar Beinlaus established a long dynasty based in Dublin, and from this base succeeded in briefly dominating large parts of central and eastern Ireland, and became traders. However, the Vikings never achieved total domination of Ireland, often fighting for and against various Irish kings, including Flann Sinna, Cerball mac Dúnlainge and Niall Glúndub. Ultimately they were suborned by King Máel Sechnaill mac Domnaill of Meath at the battle of Tara in 980.

First king of Ireland

Two branches of the descendants of Niall Noigiallach, the Cenél nEogain, of the northern Uí Néill, and the Clan Cholmáin, of the southern Uí Néill, alternated as kings of Ireland from 734 to 1002. Brian Boru (941 - 1014) became the first High King of all Ireland (árd rí Éireann) in 1002. King Brian Boru subsequently united most of the Irish Kings and Chieftains to defeat the Danish King of Dublin who led an army of Irish and Vikings at the Battle of Clontarfin 1014.

An unsettled period followed the Battle of Clontarf, in which high kings succeeding Brian Boru were unable to assert complete rule. The kings of Munster and Connaught, Leinster and Ulster allied with the ecclesiastical reform movement of western Europe as it extended into Ireland in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. A system of dioceses corresponding with the chief petty kingdoms was set up, with the archbishopric of Armagh at the head of this hierarchy, in association with the province of Ulster which was dominated by the royal family of Uí Néill.

The Anglo-Norman invasion

By the twelfth century, power was exercised by the heads of a few regional dynasties vying against each other for supremacy over the whole island. One of these, the King of Leinster Diarmait Mac Murchada was forcibly exiled from his kingdom by the new High King, Ruaidri mac Tairrdelbach Ua Conchobair. Fleeing to Aquitaine, Diarmait obtained permission from Henry II to use the Norman forces to regain his kingdom. The first Norman knight landed in Ireland in 1167, followed by the main forces of Normans, Welsh and Flemings in Wexford in 1169. Within a short time Leinster was regained, Waterford and Dublin were under the control of Diarmait, who named his son-in-law, Richard de Clare, heir to his kingdom.

This caused consternation to King Henry II of England, who feared the establishment of a rival Norman state in Ireland. Accordingly, he resolved to establish his authority. With the authority of the papal bull Laudabiliter from Adrian IV, Henry landed with a large fleet at Waterford in 1171, becoming the first King of England to set foot on Irish soil. Henry awarded his Irish territories to his younger son John with the title Dominus Hiberniae ("Lord of Ireland"). When John unexpectedly succeeded his brother as King John, the "Lordship of Ireland" fell directly under the English Crown.

The Lordship of Ireland

Initially the Normans controlled the entire east coast, from Waterford up to eastern Ulster and penetrated as far west as Galway, Kerry and Mayo. The most powerful lords in the land were the great Hiberno-Norman Lord of Leinster from 1171, Earl of Meath from 1172, Earl of Ulster from 1205, Earl of Connaught from 1236, Earl of Kildare from 1316, the Earl of Ormonde from 1328 and the Earl of Desmond from 1329 who controlled vast territories, known as Liberties which functioned as self-administered jurisdictions with the Lordship of Ireland owing feudal fealty to the King in London. The first Lord of Ireland was King John, who visited Ireland in 1185 and 1210 and helped consolidate the Norman-controlled areas, while at the same time ensuring that the many Irish kings swore fealty to him.

The Norman-Irish established feudal baronies, manors, towns and large land-owning monastic communities, and the county system through most of the lowlands. King John established a civil government independent of the feudal lords, divided the country into counties for administrative purposes, introduced English law, and sought to reduce feudal "liberties," which were lands held in the personal control of aristocratic families and the church. The Irish Parliament paralleled that of its English counterpart.

Throughout the thirteenth century, the English Kings aimed to weaken the power of the Norman Lords in Ireland.

Gaelic resurgence

By 1261 the weakening of the Anglo-Normans had become manifest when Fineen Mac Carthy defeated a Norman army at the Battle of Callann, County Kerry, and killed John fitz Thomas, Lord of Desmond, his son Maurice fitz John and eight other barons. In 1315, Edward Bruce of Scotland invaded Ireland, gaining the support of many Gaelic lords against the English. Although Bruce was eventually defeated at the Battle of Faughart, the war caused a great deal of destruction, especially around Dublin. In this chaotic situation, local Irish lords won back large amounts of land that their families had lost since the conquest and held them after the war was over.

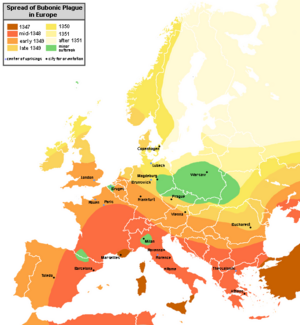

The Black Death arrived in Ireland in 1348. Because most of the English and Norman inhabitants of Ireland lived in towns and villages, the plague hit them far harder than it did the native Irish, who lived in more dispersed rural settlements. After it had passed, Gaelic Irish language and customs came to dominate the country again. The English-controlled area shrunk back to the Pale, a fortified area around Dublin that ran through the counties of Louth, Meath, Kildare and Wicklow, and the Earldoms of Kildare, Ormonde and Desmond.

Outside the Pale, the Hiberno-Norman lords adopted the Irish language and customs, becoming known as the Old English, and in the words of a contemporary English commentator, became "more Irish than the Irish themselves." Over the following centuries they sided with the indigenous Irish in political and military conflicts with England and stayed Catholic after the Reformation.

By the end of the fifteenth century, central English authority in Ireland had all but disappeared. England's attentions were diverted by its Wars of the Roses (civil war). The Lordship of Ireland lay in the hands of the powerful Fitzgerald Earl of Kildare, who dominated the country by means of military force and alliances with lords and clans around Ireland. Around the country, local Gaelic and Gaelicised lords expanded their powers at the expense of the English government in Dublin.

The Reformation

The Reformation, before which, in 1532, Henry VIII broke with Papal authority, fundamentally changed Ireland. While Henry VIII broke English Catholicism from Rome, his son Edward VI moved further, breaking with Papal doctrine completely. While the English, the Welsh and, later, the Scots accepted Protestantism, the Irish remained Catholic. This influenced their relationship with England for the next four hundred years, as the Reformation coincided with a determined effort on behalf of the English to re-conquer and colonize Ireland. This sectarian difference meant that the native Irish and the (Roman Catholic) Old English were excluded from political power.

Re-conquest and rebellion

From 1536, Henry VIII decided to re-conquer Ireland. The Fitzgerald dynasty of Kildare, who had become the effective rulers of Ireland in the fifteenth century, had invited Burgundian troops into Dublin to crown the Yorkist pretender, Lambert Simnel as King of England in 1497. Again in 1536, Silken Thomas Fitzgerald went into open rebellion against the crown. Having put down this rebellion, Henry VIII resolved to bring Ireland under English government control so the island would not become a base for future rebellions or foreign invasions of England.

In 1541, Henry upgraded Ireland from a lordship to a full Kingdom, and Henry was proclaimed King of Ireland at a meeting of the Irish Parliament attended by the Gaelic Irish chieftains as well as the Hiberno-Norman aristocracy. The re-conquest was completed during the reigns of Elizabeth and James I, after several bloody conflicts—the Desmond Rebellions (1569–1573 and 1579–1583 and the Nine Years War 1594–1603.

After this point, the English authorities in Dublin established real control over Ireland for the first time, bringing a centralized government to the entire island, and successfully disarmed the native lordships. However, the English were not successful in converting the Catholic Irish to the Protestant religion and the brutal methods used by crown authority to pacify the country heightened resentment of English rule.

From the mid-sixteenth and into the early seventeenth centuries, crown governments carried out a policy of colonization known as Plantations. Scottish and English Protestants were sent as colonists to the provinces of Munster, Ulster and the counties of Laois and Offaly. These settlers, who had a British and Protestant identity, would form the ruling class of future British administrations in Ireland. A series of Penal Laws discriminated against all faiths other than the established (Anglican) Church of Ireland. The principal victims of these laws were Catholics and later Presbyterians.

Civil wars and penal laws

The seventeenth century was perhaps the bloodiest in Ireland's history. Two periods of civil war (1641-1653 and 1689-1691) caused huge loss of life and resulted in the final dispossession of the Irish Catholic landowning class and their subordination under the Penal Laws. Irish Catholics rebelled against English and Protestant domination in 1641, and killed thousands of Protestant settlers. The Catholic gentry briefly ruled the country as Confederate Ireland (1642-1649) against the background of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms until Oliver Cromwell re-conquered Ireland in 1649-1653 on behalf of the English Commonwealth. Cromwell's conquest was the most brutal phase of a brutal war. By its close, up to a third of Ireland's pre-war population was dead or in exile. As punishment for the rebellion of 1641, almost all lands owned by Irish Catholics were confiscated and given to British settlers. Several hundred remaining native landowners were transplanted to Connacht.

Ireland became the main battleground after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, when the Catholic James II left London and the English Parliament replaced him with William of Orange. The wealthier Irish Catholics backed James to try to reverse the remaining Penal Laws and land confiscations, whereas Protestants supported William to preserve their property in the country. James and William fought for the Kingdom of Ireland in the Williamite War, most famously at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690, where James's outnumbered forces were defeated. Jacobite resistance was finally ended after the Battle of Aughrim in July 1691. The Penal Laws that had been relaxed somewhat after the English Restoration were re-enacted more thoroughly after this war, as the Protestant elite wanted to ensure that the Irish Catholic landed classes would not be in a position to repeat their rebellions.

Colonial Ireland 1691-1801

Subsequent Irish antagonism towards England was aggravated by the economic situation of Ireland in the eighteenth century. Some absentee landlords managed some of their estates inefficiently, and food tended to be produced for export rather than for domestic consumption. Two very cold winters led directly to the Great Irish Famine (1740-1741), which killed about 400,000 people, affecting all of Europe. In addition, Irish exports were reduced by the Navigation Acts from the 1660s, which placed tariffs on Irish produce entering England, but exempted English goods from tariffs on entering Ireland. Some Irish Catholics remained attached to Jacobite ideology in opposition to the Protestant Ascendancy until the death of "James III & VII" in 1766. Thereafter, the Papacy recognized the Hanoverians as the legitimate rulers. Most of the eighteenth century was relatively peaceful in comparison with the preceding 200 years, and the population doubled to over four million.

By the late eighteenth century, many of the Irish Protestant elite had come to see Ireland as their native country. A parliamentary faction led by Henry Grattan agitated for a more favorable trading relationship with England and for greater legislative independence for the Parliament of Ireland. However, reform in Ireland stalled over the more radical proposals to enfranchise Irish Catholics. This was enabled in 1793, but Catholics could not yet enter parliament or become government officials. Some were attracted to the more militant example of the French Revolution of 1789. They formed the Society of the United Irishmen to overthrow British rule and found a non-sectarian republic. Their activity culminated in the Irish Rebellion of 1798, which was bloodily suppressed.

Union with Great Britain

Largely in response to the 1798 rebellion, Irish self-government was abolished altogether by the Act of Union on January 1, 1801, which merged Kingdom of Ireland and the Kingdom of Great Britain (itself a union of England and Scotland, created almost 100 years earlier), to create the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Part of the deal was that discrimination against Catholics, Presbyterians, and others (Catholic emancipation), would end. However, King George III controversially blocked any change. In 1823, an enterprising Catholic lawyer, Daniel O'Connell, known as "the Great Liberator" began a successful campaign to achieve emancipation, which was finally conceded in 1829. He later led an unsuccessful campaign for "Repeal of the Act of Union."

The second of Ireland's "great famines," An Gorta Mór struck the country severely in the period 1845-1849, with potato blight leading to mass starvation and emigration. The population dropped from over eight million before the famine to 4.4 million in 1911. The Irish language, once the spoken language of the entire island, declined in use sharply in the nineteenth century, largely replaced by English.

Outside mainstream nationalism, a series of violent rebellions by Irish republicans took place in 1803, under Robert Emmet; in 1848 a rebellion by the Young Irelanders, most prominent among them, Thomas Francis Meagher; and in 1867, another insurrection by the Irish Republican Brotherhood. All failed, but physical force nationalism remained an undercurrent in the nineteenth century.

The late nineteenth century also witnessed major land reform, spearheaded by the Land League under Michael Davitt demanding what became known as the 3 Fs; Fair rent, free sale, fixity of tenure. From 1870 various British governments introduced a series of Irish Land Acts - William O'Brien playing a leading role by winning the greatest piece of social legislation Ireland had yet seen, the Wyndham Land Purchase Act (1903) which broke up large estates and gradually gave rural landholders and tenants ownership of the lands. It effectively ended absentee landlordism, solving the age old Irish Land Question.

Towards home rule

In the 1870s the issue of Irish self-government again became a focus of debate under Protestant landowner, Charles Stewart Parnell and the Irish Parliamentary Party of which he was founder. British prime minister William Gladstone, of the Conservative Party, introduced the first Home Rule Bill in Parliament in 1886. The measure was defeated, but it was the start of the Nationalist-Unionist split. Ulster Protestants opposed home rule, not trusting politicians from the Catholic agrarian south and west to support the more industrial economy of Ulster. Unionists supported union with Britain and tended to be Protestant, and nationalists advocated Irish self-government, and were usually Catholic. Out of this division, two opposing sectarian movements evolved, the Protestant Orange Order and the Catholic Ancient Order of Hibernians.

A second Home Rule Bill, also introduced by Gladstone, was defeated in 1893, while the third, and final, Home Rule Bill twice passed the House of Commons in 1912, when the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) held the balance of power in the Commons. Both times it was defeated in the House of Lords.

To resist home rule, thousands of unionists, led by the Dublin-born barrister Sir Edward Carson and James Craig, signed the "Ulster Covenant" of 1912, pledging to resist Irish independence. This movement also saw the setting up of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), the first Irish paramilitary group. Irish nationalists created the Irish Volunteers - forerunners of the Irish Republican Army (IRA).

In 1914, the Home Rule Bill of 1912 passed the House of Commons for the third time, which meant ratification by the House of Lords was unnecessary. But when war broke out in Europe, the British government postponed the operation of the Home Rule Act until after the war.

World War I

In September 1914, just as the First World War broke out, the UK Parliament finally passed the Third Home Rule Act to establish self-government for Ireland, but was suspended for the duration of the war. Nationalist leaders and the IPP under Redmond in order to ensure the implementation of Home Rule after the war, supported the British and Allied war effort against the Central Powers. The core of the Irish Volunteers were against this decision, a majority splitting off into the National Volunteers who enlisted in Irish battalions of the 10th and 16th (Irish) Divisions. Before the war ended, Britain made two concerted efforts to implement Home Rule, one in May 1916 and again with the Irish Convention during 1917-1918, but the Irish sides (Nationalist, Unionist) were unable to agree terms for the temporary or permanent exclusion of Ulster from its provisions.

Easter 1916 uprising

A failed attempt was made to gain separate independence for Ireland with the 1916 Easter Rising, an insurrection in Dublin. Though support for the insurgents was small, the violence used in its suppression led to a swing in support of the rebels. In addition, the unprecedented threat of Irishmen being conscripted to the British Army in 1918 (for service on the Western Front as a result of the German Spring Offensive) accelerated this change. In the December 1918 elections most voters voted for Sinn Féin, the party of the rebels. Having won three-quarters of all the seats in Ireland, its MPs assembled in Dublin on January 21, 1919, to form a 32-county Irish Republic parliament, Dáil Éireann unilaterally, asserting sovereignty over the entire island.

Irish War of Independence

Unwilling to negotiate any understanding with Britain short of complete independence, the Irish Republican Army—the army of the newly declared Irish Republic—waged a guerrilla war (the Irish War of Independence) from 1919 to 1921. In the course of the fighting and amid much acrimony, the Fourth Government of Ireland Act 1920 implemented Home Rule while separating the island into what the British government's Act termed "Northern Ireland" and "Southern Ireland."

In mid-1921, the Irish and British governments signed a truce that halted the war. In December 1921, representatives of both governments signed an Anglo-Irish Treaty. The Irish delegation was led by Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins. This abolished the Irish Republic and created the Irish Free State, a self-governing Dominion of the British Empire in the manner of Canada and Australia. Under the Treaty, Northern Ireland could opt out of the Free State and stay within the United Kingdom: it promptly did so. In 1922, both parliaments ratified the Treaty, formalizing independence for the 26-county Irish Free State (which went on to become the Republic of Ireland in 1949); while the six county Northern Ireland, gaining Home Rule for itself, remained part of the United Kingdom. For most of the next 75 years, each territory was strongly aligned to either Catholic or Protestant ideologies, although this was more marked in the six counties of Northern Ireland.

Civil war

The treaty to sever the Union divided the republican movement into anti-Treaty (who wanted to fight on until an Irish Republic was achieved) and pro-Treaty supporters (who accepted the Free State as a first step towards full independence and unity). Between 1922 and 1923 both sides fought the bloody Irish Civil War. The new Irish Free State government defeated the anti-Treaty remnant of the Irish Republican Army. This division among nationalists still colors Irish politics today, specifically between the two leading Irish political parties, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael.

Irish Free State

The new Irish Free State (1922–1937) existed against the backdrop of the growth of dictatorships in mainland Europe and a major world economic downturn in 1929. In contrast with many contemporary European states it remained a democracy. Testament to this came when the losing faction in the Irish civil war, Eamon de Valera's Fianna Fáil, was able to take power peacefully by winning the 1932 general election. Nevertheless, up until the mid 1930s, considerable parts of Irish society saw the Free State through the prism of the civil war, as a repressive, British imposed state. It was only the peaceful change of government in 1932 that signaled the final acceptance of the Free State on their part. In contrast to many other states in the period, the Free State remained financially solvent as a result of low government expenditure. However, unemployment and emigration were high. The population declined to a low of 2.7 million recorded in the 1961 census.

The Roman Catholic Church had a powerful influence over the Irish state for much of its history. The clergy's influence meant that the Irish state had very conservative social policies, banning, for example, divorce, contraception, abortion, pornography as well as encouraging the censoring of many books and films. In addition the Church largely controlled the State's hospitals, schools and remained the largest provider of many other social services.

With the partition of Ireland in 1922, 92.6 percent of the Free State's population were Catholic while 7.4 percent were Protestant. By the 1960s, the Protestant population had fallen by half. Although emigration was high among all the population, due to a lack of economic opportunity, the rate of Protestant emigration was disproportionate in this period. Many Protestants left the country in the early 1920s. The Catholic Church had also issued a decree, known as Ne Temere, whereby the children of marriages between Catholics and Protestants had to be brought up as Catholics. From 1945, the emigration rate of Protestants fell and they became less likely to emigrate than Catholics - indicating their integration into the life of the Irish State.

World War II

In 1937, a new Constitution of Ireland proclaimed the state of Éire (or Ireland). The state remained neutral throughout World War II, a time termed The Emergency, and this saved it from much of the horrors of the war, although tens of thousands volunteered to serve in the British forces. Ireland was also hit badly by rationing of food, and coal in particular (peat production became a priority during this time). Though nominally neutral, recent studies have suggested a far greater level of involvement by the South with the Allies than was realized, with D Day's date set on the basis of secret weather information on Atlantic storms supplied by Éire.

Republic declared

In 1949 the state was formally declared the Republic of Ireland and it left the British Commonwealth. In the 1960s, Ireland underwent a major economic change under reforming Taoiseach (prime minister) Seán Lemass and Secretary of the Department of Finance T.K. Whitaker, who produced a series of economic plans. Free second-level education was introduced by Donnchadh O'Malley as Minister for Education in 1968. From the early 1960s, the Republic sought admission to the European Economic Community but, because 90 percent of the export economy still depended on the United Kingdom market, it could not do so until the UK did, in 1973.

Stagnation

Global economic problems in the 1970s, augmented by a set of misjudged economic policies followed by governments, including that of Taoiseach Jack Lynch, caused the Irish economy to stagnate. The Troubles in Northern Ireland discouraged foreign investment. Devaluation was enabled when the Irish Pound, or Punt, was established in as a truly separate currency in 1979, breaking the link with the UK's sterling.

The Troubles

The Troubles is a term used to describe the latest installment of periodic communal violence involving Republican and Loyalist paramilitary organisations, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), the British Army and others in Northern Ireland from the late 1960s until the Belfast Agreement of April 10, 1998. The Troubles consisted of about 30 years of repeated acts of intense violence between elements of Northern Ireland's nationalist community (principally Roman Catholic) and unionist community (principally Protestant). The conflict was caused by the disputed status of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom and the domination of the minority nationalist community, and alleged discrimination against them, by the unionist majority. The violence was characterized by the armed campaigns of paramilitary groups. Most notable of these was the Provisional IRA campaign of 1969–1997 which was aimed at the end of British rule in Northern Ireland and the creation of a new, "all-Ireland," Irish Republic.

Celtic tiger unleashed

However, economic reforms in the late 1980s, the end of the Troubles, helped by investment from the European Community, led to the emergence of one of the world's highest economic growth rates, with mass immigration (particularly of people from Asia and Eastern Europe) as a feature of the late 1990s. This period came to be known as the Celtic Tiger and was focused on as a model for economic development in the former Eastern Bloc states, which entered the European Union in the early 2000s. Property values had risen by a factor of between four and ten between 1993 and 2006, in part fueling the boom.

Irish society also adopted relatively liberal social policies during this period. Divorce was legalized, homosexuality decriminalized, while abortion in limited cases was allowed by the Irish Supreme Court in the X Case legal judgment. Major scandals in the Roman Catholic Church, both sexual and financial, coincided with a widespread decline in religious practice, with weekly attendance at Roman Catholic Mass halving in twenty years. A series of tribunals set up from the 1990s have investigated alleged malpractices by politicians, the Catholic clergy, judges, hospitals and the Gardaí (police).

Government and politics

Structure

The politics of the Republic of Ireland take place in a framework of a parliamentary representative democratic republic. The Uachtarán (president) is the head of state. The Taoiseach (prime minister) is the head of government], and of a pluriform multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and the Oireachtas the bicameral national parliament, which consists of Dáil Éireann and Seanad Éireann. The judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature. While there are a number of political parties, politics are dominated by Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, historically opposed and competing entities. The state is a member of the European Union.

The state operates under the Constitution of Ireland, officially known as Bunreacht na hÉireann, adopted in 1937, which falls within the liberal democratic tradition.

The president, who serves as head of state, and is elected for a seven-year term and can be re-elected only once, is largely a figurehead but can still carry out certain constitutional powers and functions, aided by the Council of State, an advisory body.

Executive authority is exercised by a cabinet known simply as the Government. The cabinet may consist of between seven and 15 members, namely the Taoiseach (prime minister), the Tánaiste (deputy prime minister), and up to 13 other ministers. The Taoiseach, normally the leader of the political party which wins the most seats in the national elections, is appointed by the president, after being nominated by Dáil Éireann (the lower house of parliament). The remaining ministers are nominated by the Taoiseach and appointed by the president following their approved by the Dáil.

The bicameral parliament is the Oireachtas, which consists of the president and two houses: Dáil Éireann and Seanad Éireann (also known as the Senate). The Dáil is by far the dominant House of the legislature. The president may not veto bills passed by the Oireachtas, but may refer them to the Irish Supreme Court for a ruling on whether they comply with the constitution.

The 166 members of the Dáil (Teachta Dála) are directly elected at least once in every five years under the single transferable vote form of proportional representation from mulit-seat constituencies. The Taoiseach, Tánaiste and the Minister for Finance must be members of the Dáil.

The Seanad Éireann (senate) is largely an advisory body, and consists of 60 senators. An election for the Seanad must take place no later than 90 days after a general election for the members of the Dáil. Eleven senators are nominated by the Taoiseach while a further six are elected by certain national universities. The remaining 43 are elected from special vocational panels of candidates, the electorate for which consists of the 60 members of the outgoing senate, the 166 members of the recently elected Dáil and the 883 elected members of Ireland's 29 County Borough Councils. Suffrage is universal to those aged 18 years and over.

The judiciary consists of the Supreme Court, the High Court, and many lower courts. Judges are appointed by the president after being nominated by the Government, and can be removed from office only for misbehavior or incapacity, and then only by resolution of both houses of the Oireachtas. The final court of appeal is the Supreme Court, which consists of the Chief Justice and seven other justices. The Supreme Court has the power of judicial review and may rule on the constitutionality of laws and acts of the state. The legal system is based on English common law, substantially modified by indigenous concepts. Ireland has not accepted compulsory International Court of Justice jurisdiction.

Ireland has had a long history of political violence, which remained a key aspect of life in Northern Ireland, where paramilitary groups like the Irish Republican Army were supported by people in the republic.

Ireland joined the European Union in 1973 but has chosen to remain outside the Schengen Treaty. Citizens of the UK can freely enter Ireland without a passport thanks to the Common Travel Area, however some form of identification is required at airports and seaports.

Counties

The Republic of Ireland traditionally had 26 counties, and these are still used in cultural and sporting contexts. Dáil constituencies are required by statute to follow county boundaries, as far as possible. Hence counties with greater populations have multiple constituencies (for example, Limerick East/West) and some constituencies consist of more than one county (for example, Sligo-North Leitrim).

As local government units, however, some have been restructured, giving a present-day total of 29 administrative counties and five cities—Dublin, Cork, Limerick, Galway, and Waterford. Five boroughs—Clonmel, Drogheda, Kilkenny, Sligo and Wexford—have a level of autonomy within the county.

Military

Ireland's armed forces are organized under the Irish Defence Forces (Óglaigh na hÉireann). The Irish Army is relatively small compared to other neighboring armies in the region, but is well equipped, with 8500 full-time military personnel (13,000 in the reserve army). This is principally due to Ireland's policy of neutrality, and its "triple-lock" rules governing participation in conflicts. Deployments of Irish soldiers cover UN peace-keeping duties, protection of the Republic's territorial waters (in the case of the Irish Naval Service) and Aid to Civil Power operations in the state.

There is also an Irish Air Corps and Reserve Defence Forces (Irish Army Reserve and Naval Service Reserve) under the Defence Forces. The Irish Army Rangers is a special forces branch which operates under the aegis of the army. Over 40,000 Irish servicemen have served in UN peacekeeping missions around the world.

The republic supplies support to the USA military. Most military personnel involved in the 2003 invasion of Iraq travelled through Shannon Airport, which had previously been used for the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001. The airport was used previously by the US in the First Gulf War and by the Soviet Union during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

In 2007, the Republic of Ireland was ranked first in the world for political freedom, press freedom and literacy, third for Economic Freedom, and fourth on the Human Development Index.

Religion

Religious freedom is constitutionally provided for in Ireland. Christianity is the predominant religion, and Ireland is predominantly Catholic country. However, there has been a major decline in this attendance among Irish Catholics in the course of the past 30 years. Between 1996 and 2001, regular Mass attendance, declined further from 60 percent to 48 percent (it had been above 90 percent before 1973), and all but two of its seminaries have closed (St Patrick's College, Maynooth, and St Malachy's College, Belfast). A number of theological colleges continue to educate both ordained and lay people.

The patron saints of Ireland are Saint Patrick and Saint Bridget.

Catholic doctrine and the constitution

The 1937 Constitution of Ireland gave the Roman Catholic Church a "special position" as the church of the majority, but also recognized other Christian denominations and Judaism. As with other predominantly Roman Catholic European states such as Italy, the Irish state underwent a period of legal secularization in the late twentieth century. In 1972, the articles mentioning specific religious groups, including the Catholic Church, were deleted from the Irish constitution by the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland.

Article 44, which remains in the constitution, says that:

The State acknowledges that the homage of public worship is due to Almighty God. It shall hold His Name in reverence, and shall respect and honor religion.

The article also establishes freedom of religion, prohibits endowment of any particular religion, prohibits the state from religious discrimination, and requires the state to treat religious and non-religious schools in a non-prejudicial manner.

Catholic doctrine prohibits abortion in all circumstances, putting it in conflict with the pro-choice movement. In 1983, the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland recognized "the right to life of the unborn," subject to qualifications concerning the "equal right to life" of the mother. The case of Attorney General v. X prompted passage of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, guaranteeing the right to travel abroad to have an abortion performed, and the right of citizens to learn about "services" that are illegal in Ireland but legal outside the country.

Catholic and Protestant attitudes in 1937 also disapproved of divorce, which was prohibited by the original constitution. It was not until 1995 that the Fifteenth Amendment repealed this ban.

The Catholic Church was hit in the 1990s by a series of sexual abuse scandals and cover-up charges against its hierarchy. In 2005, a major inquiry was made into child sexual abuse allegations. The Ferns report, published on October 25, 2005, revealed that more than 100 cases of child sexual abuse, between 1962 and 2002, by 21 priests, had taken place in the Diocese of Ferns alone. The report criticized the Gardaí and the health authorities, who failed to protect the children to the best of their abilities; and in the case of the Garda before 1988, no file was ever recorded on sexual abuse complaints.

Despite most schools in Ireland being run by religious organizations, a general trend of secularism is occurring within the Irish population, particularly in the younger generations. Many efforts have been made by secular groups to eliminate the rigorous study of prayer in the first and sixth classes, to prepare for the sacraments of holy communion and confirmation. However religious studies as a subject was introduced into the state administered "Junior certificate" in 2001.

In the past, Ireland has historically favored conservative legislation regarding sexuality. For example, contraception was illegal in Ireland until 1979. Another example is the legislation which outlawed homosexual acts was not repealed until 1993 although it was generally only enforced when dealing with underage sex. Though Senator David Norris took his successful case to the European Court of Human Rights in 1988, the Irish Government did not legislate to rectify the issue until 1993.

Economy

As archaeological evidence from sites such as the Céide Fields in County Mayo and Lough Gur in County Limerick demonstrates, farming in Ireland is an activity that goes back to the very beginnings of human settlement. Texts such as the Táin Bó Cúailinge show a society in which cattle represented a primary source of wealth and status. Little of this had changed by the time of the Norman conquest of Ireland in the twelfth century. Irish peasants were among the first in Europe to be able to buy their landholdings. Even today, when a quarter of the population of the Republic lived in Dublin, the cattle population is of the order of 6.7 million.

Most farms are family-owned. Cooperatives handle production and marketing. Pasture and arable land is leased out for 11 months of each year in a traditional system known as conacre.

The economy of Ireland has transformed in recent years from an agricultural focus to one dependent on trade, industry, and investment.

Exports play a fundamental role in the state's robust growth, but the economy also benefits from the accompanying rise in consumer spending, construction, and business investment. On paper, the country is the largest exporter of software-related goods and services in the world. In fact, a lot of foreign software, and sometimes music, is filtered through the country to avail of the state's non-taxing of royalties from copyrighted goods.

A key part of economic policy, since 1987, has been Social Partnership which is a neo-corporatist set of voluntary "pay pacts" between the Government, employers and trades unions. These usually set agreed pay rises for three-year periods.

The state joined in launching the Euro currency system in January 1999 (leaving behind the Irish pound) along with 11 other EU nations.

Taxation

Governments have favored a low taxation policy to encourage foreign direct investment in Ireland. Consequently, the government opposes moves by the European Commission to restrict tax competition. The corporate tax rate is only 12.5 percent, versus between 15 percent and 60 percent in the rest of Europe. The income tax system is designed to redistribute wealth from the richer to the poorer segments of society. There are two tax bands, based on income levels. These range from a maximum top rate of 41 percent, to a maximum bottom rate of 20 percent. In reality, however, a generous tax credits system ensures that the lower rates of taxation are normally 4 percent to 12 percent. The top rate of tax never exceeds 35 percent in practice.

The government receives much of its revenues from taxes on goods—these include a 21 percent VAT rate on most consumer goods, high levels of excise duty on tobacco, petrol, and alcohol and several smaller taxes on items such as plastic bags, cheques, ATM cards, credit cards and debit cards; the taxes in the personal financial sector.

Wealth disparities

Large disparities in wealth exist between those employed and those dependent on welfare payments. The percentage of the population at risk of relative poverty was 21 percent in 2004 - one of the highest rates in the European Union. Poverty figures show that 6.8 percent of Ireland's population suffer "consistent poverty."

Several successive years of unbalanced economic growth have also led to huge inequality between the strata of Irish society. Large and sustained increases in property values from 2002-2006 have had a substantial impact on the distribution of wealth. The high level of inequality in Ireland today is evident from an annual publication issued by the Bank of Ireland detailing the sources of wealth in the nation.

The Irish government runs a Welfare state system. The government provides free education at all levels for all EU citizens. Free healthcare is not universal, being restricted to the unemployed and very low earners at the General practitioner level. People who are unemployed receive unemployment benefits and retired people are entitled to a state pension - both benefits are quite high by international comparisons.

Transport

The Republic of Ireland has three main international airports (Dublin, Shannon, and Cork) that serve a wide variety of European and intercontinental routes with scheduled and chartered flights. The national airline is Aer Lingus, although low cost airline Ryanair is the largest airline. The route between London and Dublin is the busiest international air route in Europe, with 4.5 million people flying between the two cities in 2006.

Railways services are provided by Iarnród Éireann. Dublin is the center of the network, with two main stations (Heuston and Connolly) linking to the main towns and cities. The Enterprise service, run jointly with Northern Ireland Railways connects Dublin with Belfast. The motorways and major trunk roads are managed by the National Roads Authority. The rest of the road network is managed by the local authorities in each of their areas. Regular ferry services operate between the Republic of Ireland and Great Britain, the Isle of Man and France.

On independence, the cities of Dublin and Cork both had extensive light rail networks, as did many parts of the country-side, such as the West-Clare and West-Kerry railways. Cork's light rail network was removed from service in 1931, and trams in Dublin were phased out between 1940 and 1944. Tram lines were dug up, and equipment and facilities sold-off. Tram service in Ireland was not operated again in Ireland until 2004, when the first two lines of a new light-rail system known as Luas, were opened in Dublin. It features on-street running in the city center, but is considered a light-rail system because it runs along a dedicated right-of-way for much of its route.

Demographics

Ethnicity

Genetic research suggests that the first settlers of Ireland, and parts of North-Western Europe, came through migrations from Iberia following the end of the most recent ice age Neolithic and Bronze Age migrants represent a minority of Irish genetic heritage, although the Gaelic traditions they brought, became the dominant culture. Today, Irish people are mainly of Gaelic ancestry, and although some of the population is also of Norse, Anglo-Norman, English, Scottish, French and Welsh ancestry, these groups have been assimilated and do not form distinct minority groups. The itinerant Irish Travelers, also known as Tinkers, are an ethnic minority group, politically (but not ethnically) linked with mainland European Roma and Gypsy groups.

Languages

The official languages are Irish and English. Irish (Gaeilge) is a Celtic language of the Goidelic language family branch. Although once spoken across the whole of the island, it is a minority vernacular in Ireland, spoken in specific communities and most particularly in the officially-recognized Gaeltacht, which exists in six separate communities around the republic. Teaching of the Irish and English languages is compulsory in the primary and secondary level schools that receive money and recognition from the state. Some students may be exempt from the requirement to receive instruction in either language.

English is by far the predominant language spoken throughout the country. People living in predominantly Irish-speaking Gaeltacht regions, are limited to the low tens of thousands in isolated pockets largely on the western seaboard. Road signs are usually bilingual, except in Gaeltacht regions, where they are in Irish only. The legal status of place names has recently been the subject of controversy, with an order made in 2005 under the Official Languages Act changing the official name of certain locations from English back to Irish (for example, Dingle had its name changed to An Daingean, but was then renamed to "Dingle Daingean Ui Chuis"), sometimes despite local opposition, and, in Dingle's case, a plebiscite requesting a name change to a bilingual version. Most public notices are only in English, as are most of the print media. Most Government publications and forms are available in both English and Irish, and citizens have the right to deal with the state in Irish if they so wish. National media in Irish exist on TV (TG4), radio (Raidió na Gaeltachta), and in print (Lá Nua and Foinse).

Other languages spoken in Ireland include Shelta, spoken by the Irish Traveler population and a dialect of Scots is spoken by the descendants of Scottish settlers in Ulster.

Men and women

While equal pay for equal work is guaranteed by law, inequities persist between the genders in pay, in access to professional achievement, and in respect at work.

Marriage and the family

Marriages are seldom arranged, since most spouses are selected through the individual process of trial and error that characterizes Western European society. Marriages are normally monogamous. Divorce has been legal since 1995. Rural society places great pressure on men and women to marry, especially in poor rural areas where many women leave for the cities or emigrate seeking work and social standing matching their education and expectations. Rural marriage festivals, the most famous of which takes place in Lisdoonvarna, brings people together for marriage matches, but face criticism.

The nuclear family is the principal domestic unit, although extended families continue to play important roles. Children adopt their father's surnames. First names are often selected to honor a grandparent, and in the Catholic tradition most first names are those of saints. Many families use the Irish form of their names, and children in the national primary school system are taught to know and use the Irish language equivalent of their names.

The Constitution of Ireland guarantees the rights of the family and the institution of marriage. However, the reality is that social and economic change has brought about significant changes in family life in the Republic. In the Republic, divorce became legal on February 27, 1997.

Education

Education and literacy are emphasized. A total 99.9 percent of the population aged 15 and over can read and write, putting the republic at first place in the world for literacy. Ireland's education system is quite similar to that of most other western countries. There are three levels of education: primary, secondary and tertiary education. Further education has grown immensely. Growth in the economy since the 1960s has driven much of the change in the education system.

English is the primary medium of instruction at all levels, except in Gaelscoileanna: schools in which Irish is the working language and which are increasingly popular. Universities also offer degree programs in diverse disciplines, taught mostly through English, with some in Irish.

All children must receive compulsory education between the ages of six and 15 years, inclusive. The primary school system consists of eight years—junior and senior infants (corresponding to kindergarten), and first to sixth classes. Most children attend primary school between the ages of four and 12. The Primary School Curriculum (1999), taught in all schools, seeks to celebrate the uniqueness of the child.

Most students attend and complete secondary education, with approximately 90 percent of school-leavers taking the terminal examination, the Leaving Certificate. Secondary education is generally completed at a community school, a comprehensive school, a vocational school or a voluntary secondary school. A typical secondary school will consist of first to third year (with the Junior Certificate at the end of third), the usually optional transition year (though compulsory in some schools), and fifth and sixth year (with the leaving Certificate at the end of sixth).

Higher (or third-level) education awards in Ireland are conferred by Dublin City University, Dublin Institute of Technology, Higher Education and Training Awards Council, National University of Ireland, University of Dublin, and University of Limerick. These are the degree-awarding authorities approved by the Irish Government and can grant awards at all academic levels. The King's Inns of Dublin has a limited role in education specializing in the preparation of candidates for the degree of barrister-at-law to practice as barristers.

Technically, the majority of Ireland's primary and secondary schools are owned by the Catholic parishes. The parish's school is run by the Board of Management on behalf of the local community. With increasing numbers of non-Catholics in Ireland, the question of Catholic school ethos has become contested. The state provides and pays for the teachers, organizes the curriculum and agrees to provide examinations and other centralized services for these schools.

Control of schools is technically vested in the Catholic Church/Church of Ireland/church grouping, but as the state decides the content of educational curricula with various interests, including the churches, the state has effective control.

Class

The Irish regard their culture as egalitarian, reciprocal, and informal. While an English-style rigid class structure is absent, social and economic class distinctions persist through educational and religious institutions, and the professions. At the top of Irish society is a class of wealthy people, who have made fortunes in business, the professions, the arts and through sport. There is a working class, and a middle class. Relative wealth and social class influence choice of school and university, which affects class mobility. Use of language, especially dialect, indicates class and other social standing. Dress codes have relaxed, but designer clothing, good food, travel, and expensive cars and houses, all reflect degrees of wealth.

Culture

Architecture

The architecture of Ireland is one of the most visible features in the Irish countryside - with remains from all eras since the stone age abounding. Ireland is famous for its ruined and intact Norman and Anglo-Irish castles, small whitewashed thatched cottages and Georgian urban buildings. What are unaccountably somewhat less famous are the great, still complete palladian and rococo country houses which can be favorably compared to anything similar in northern Europe, and the country's many mighty Gothic and neo-Gothic cathedrals and buildings. Despite the ofttimes significant British and European influence, the fashion and trends of architecture have been adapted to suit the peculiarities of the particular location.

In the late twentieth century a new economic climate resulted in a renaissance of Irish culture and design, placing some of Ireland's cities, once again, at the cutting edge of modern architecture. Irish architecture followed the international trend towards modern, sleek and often radical building styles, particularly after independence in the first half of the century. New building materials and old were utilized in new ways to maximize style, space, light and energy efficiency. Ireland's first all-concrete Art Deco church was built in Turners Cross, Cork, in 1928. In 1953, one of Ireland's most radical buildings, Bus Éireann's main Dublin terminal building, better known as Busáras was completed. It was built despite huge public opposition, excessive costs (over £1m) and even opposition from the Catholic Church.

Art

The early history of Irish visual art is generally considered to begin with early carvings found at sites such as Newgrange and is traced through Bronze Age artifacts, particularly ornamental gold objects, and the religious carvings and illuminated manuscripts of the medieval period. During the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, a strong indigenous tradition of painting emerged, including such figures as John Butler Yeats (the father of poet William Butler Yeats, William Orpen and Jack Yeats.

Ireland's best known contemporary artists include Louis le Brocquy, a figurative painter and print maker, Sean Scully an abstract expressionist who lives and works in New York, Dorothy Cross, a sculptor and filmmaker and James Coleman, an installation and video artist.

Interest in collecting Irish art has expanded rapidly with the economic expansion of the country, primarily focusing on investment in early twentieth century painters. Support for young Irish artists is still relatively minor compared to their European counterparts, as the Arts Council's focus has been on improving infrastructure and professionalism in venues. That said, Ireland's unique tax break for creative artists (writers, visual artists and composers) has encouraged a wide community of artists to remain in Ireland.

Literature

For a comparatively small country, Ireland has made a disproportionate contribution to world literature in all its branches, in both the Irish and English languages. The works that are best known outside the country are in English. For example, in the twentieth century, Ireland produced four winners of the Nobel Prize for Literature; George Bernard Shaw (1925), William Butler Yeats (1923), Samuel Beckett (1969), and Seamus Heaney (1995). Three of these were born in Dublin (Heaney being the exception, who has lived in Dublin but was born in County Londonderry), making it the birthplace of more Nobel literary laureates than any other city in the world. The Irish language has the third oldest literature in Europe (after Greek and Latin) the most significant body of written literature (both ancient and recent) of any Celtic languageas well as a strong oral tradition of legends and poetry. Poetry in Irish represents the oldest vernacular poetry in Europe, with the earliest examples dating from the sixth century.

Ireland has produced the Book of Kells, and writers such as George Berkeley, Jonathan Swift, James Joyce, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, Oliver Goldsmith, Oscar Wilde, Patrick Kavanagh, John Millington Synge, Seán O'Casey, Bram Stoker and others. Other prominent writers include John Banville, Roddy Doyle, Pádraic Ó Conaire, Máirtín Ó Cadhain, Séamus Ó Grianna, Dermot Bolger, Maeve Binchy, Frank McCourt, Edna O'Brien, Joseph O'Connor, John McGahern, and Colm Tóibín.

Science

Founder of modern chemistry Robert Boyle was a seventeenth-century Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, inventor and early gentleman scientist, noted for his work in physics and chemistry. He is best known for the formulation of Boyle's law.

Irish mathematician and physicist John Lighton Synge made progress in classical mechanics, general mechanics, geometrical optics, gas dynamics, hydrodynamics, elasticity, electrical networks, mathematical methods, differential geometry, and Einstein’s theory of relativity.

Physicist Ernest Walton, winner of the 1951 Nobel Prize in Physics (along with Sir John Douglas Cockcroft), helped develop a new theory of Wave equation, which led to a new era of accelerator-based experimental nuclear physics.

Physicist George Johnstone Stoney, the uncle of the physicist George FitzGerald and distant relative of mathematician Alan Turing, is famous for introducing the term electron in 1874. The Planck scale, which contemporary physics has settled on as the most suitable scale for a unified theory, was anticipated by Stoney. Like Planck after him, Stoney realized that large-scale effects such as gravity and small-scale effects such as electromagnetism naturally imply an intermediate scale where physical differences might be rationalized.

Physicist Joseph Larmor published the Lorentz transformations some two years before Hendrik Lorentz (1899, 1904) and eight years before Albert Einstein (1905). Physicist George Francis FitzGerald is best known for his conjecture in 1889 that if all moving objects were foreshortened in the direction of their motion, it would account for the curious result of the Michelson-Morley experiment.

Physicist John Stewart Bell is famous as the originator of Bell's Theorem, one of the most important theorems in quantum physics. It is notable for showing that the predictions of quantum mechanics are not intuitive. Bell was nominated for a Nobel prize.

The Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies (DIAS) was established in 1940 by the Taoiseach Éamon de Valera.

Music

The Irish tradition of folk music and dance is widely known. In the middle years of the twentieth century, as Irish society was trying to modernize, traditional Irish music fell out of favor. During the 1960s, and inspired by the American folk music movement, there was a revival of interest, inspired by groups like The Dubliners, the Clancy Brothers and Sweeney's Men and individuals like Seán Ó Riada.

Before long, rock groups and musicians were incorporating elements of traditional music into a rock idiom to form a unique new sound. During the 1970s and 1980s, the distinction between traditional and rock musicians became blurred. This trend can be seen more recently in the work of bands like U2, The Cranberries and The Corrs.

In European classical music, the Island of Ireland was the birthplace of the notable composers Turlough O'Carolan, John Field (inventor of the Nocturne), Gerald Barry, Michael William Balfe, Sir Charles Villiers Stanford and Charles Wood.

The potato in Ireland

The potato, introduced into Ireland in the second half of the seventeenth century, initially as a garden crop, came to be the main food field crop. As a food source, the potato is extremely efficient in terms of energy yielded per unit area of land, and is a good source of many vitamins and minerals, particularly vitamin C (especially when fresh). As a result, the typical eighteenth and nineteenth century Irish diet of potatoes and buttermilk was a contributing factor in the population explosion that occurred at that time. However, the damp Irish climate favors the spread of potato blight and this frequently led to shortages and famine. The most notable instance being the Great Irish Famine (1845-1849, which more or less undid all the growth in population of the previous century by a combination of starvation, disease and emigration.

Pub culture

Pub culture, as it is termed, pervades Irish society. The term refers to the Irish habit of frequenting public houses (pubs) or bars. Even though Ireland has a recognized problem with over-consumption of alcohol, typically pubs are places where people can gather and meet their neighbors and friends in a relaxed atmosphere. Pubs vary widely according to the clientele they serve, and the area they are in. Best known is the traditional pub, with Irish music, tavern-like warmness, and memorabilia, which serve food, particularly during the day. Many more modern pubs use a DJ or non-traditional live music. Some larger pubs in cities opt for loud music, and focusing more on the consumption of drinks. Such venues are popular "pre-clubbing" locations.

A significant change to pub culture in the republic has been the introduction of a smoking ban, in all workplaces, which includes pubs and restaurants, in March 2004. The atmosphere in pubs has changed greatly as a result, and debate continues on whether it has boosted or lowered sales. A similar ban, under the Smoking (Northern Ireland) Order 2006 came into effect in Northern Ireland in April, 2007.

Sport

The national sports, administered by the Gaelic Athletic Association, are Gaelic football and hurling, arguably the world's fastest field team sport in terms of game play.

Also popular are football (soccer), rugby, athletics, snooker, boxing, motorsport, cycling and golf.

Notes

- ↑ CIA, Ireland: People and Society The World Factbook. Retrieved February 7, 2025.

- ↑ Ireland Population Worldometer. Retrieved February 8, 2025.

- ↑ Working from home up, Catholic households down in Census figures RTE (May 30, 2023). Retrieved February 8, 2025.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 World Economic Outlook Database, April 2024 Edition. (Ireland) International Monetary Fund. Retrieved February 8, 2025.

- ↑ Gini coefficient of equivalised disposable income – EU-SILC survey Eurostat. Retrieved February 8, 2025.

- ↑ John Coakley and Michael Gallagher (eds.), Politics in the Republic of Ireland (Routledge, 2017, ISBN 1138119458).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barry, Terry (ed.). A History of Settlement in Ireland. Routledge, 2011. ISBN 978-0415518611

- Coakley, John, and Michael Gallagher (eds.). Politics in the Republic of Ireland. Routledge, 2017. ISBN 1138119458

- Flanagan, Laurence. Ancient Ireland, Life before the Celts. Gil & MacMillan, 1998. ISBN 0717124339

- Foley, J. Anthony, and Stephen Lalor (ed.). Gill & Macmillan Annotated Constitution of Ireland. Gill & Macmillan, 1995. ISBN 071712276X

- Foster, R.F. (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of Ireland. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0192893239

- Gilland, Karin. "Ireland: Neutrality and the International Use of Force," in Philip P. Everts and Pierangelo Isernia, Public Opinion and the International Use of Force. Routledge, 2001, 143. ISBN 0415218047

- Kee, Robert. Ireland, a history. Boston: Little, Brown, 1982. ISBN 9780316485067

- Lalor, Brian (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Ireland. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003. ISBN 9780300094428