Monk

A monk (from Greek: monos meaning "alone") is a term denoting any male person who has taken religious vows of poverty and celibacy in order to dedicate himself to a life of disciplined religious practice. Monks can be found in almost every religion and known for their single-minded devotion to the religious life.

There are several specific categories of monks including cenobites, hermits, anchorites, and hesychasts. Some monks live alone (Eremitic Monasticism) while others live in a community with like-minded people (Cenobitic Monasticism), whilst always maintaining some degree of physical separation from the masses. In the English language, a distinction is also made between monks and friars, the latter being members of mendicant orders.

Etymology

A monk (Greek: μοναχός, monachos, Latin: monachus) specifies a person who leads the "monastic life," whether in solitude or in a "monastery." From early Church times, there has been a lively discussion of the meaning of the term monk (Greek: monos, "alone"), namely whether it denotes someone living alone/away from the rest of society, or someone celibate/focused on God alone.

Originally, monks were eremitic figures, living alone from the population to focus their time entirely on their religious pursuits. However, cenotobitic orders of monks eventually developed, in which the monks lived together in communities. Thus, monasteries developed that were in a strange way oxymorons of sorts since they were "communities of loners," those who wished to withdraw from the world… but not entirely. A monastery became the dwelling of one or more monks.

Types of monks

Saint Benedict of Nursia identified four kinds of monks in his Rule of Saint Benedict, which are still used today:

- 1. The cenobites live in community in a monastery, serve God under a religious rule and do so under the leadership of an abbot (or in the case of a community of women, an abbess). Benedict points out in ch. 1.13 that they are the "strong kind," which by logic of the context must mean the larger number rather than the better kind.

- 2. The hermits and anchorites have thorough experience as cenobites in a monastery. "They have built up their strength and go from the battle line in the ranks of their brothers to the single combat of the desert; self-reliant now, without the support of another, they are ready with God's help to grapple single-handed with the vices of body and mind." Benedict himself twice lived for prolonged periods as a hermit, which may account for the comparative length of the characteristics of their life in this list.

- 3. The Sarabaites, censured by Benedict as the most detestable kind of monks, are pretenders that have no cenobitic experience, follow no rule and have no superior.

- 4. The Gyrovagues, censured by Benedict as worse than sarabaites, are wandering monks without stability in a particular monastery. (Chapter 1: Rule of Saint Benedict)

Eastern monasticism is found in three distinct forms: anchoritic (a solitary living in isolation), cenobitic (a community living and worshiping together under the direct rule of an abbot or abbess), and the "middle way" between the two, known as the skete (a community of individuals living separately but in close proximity to one another, who come together only on Sundays and feast days, working and praying the rest of the time in solitude, but under the direction of an elder). One normally enters a cenobitic community first, and only after testing and spiritual growth would one go on to the skete or, for the most advanced, become a solitary anchorite. However, one is not necessarily expected to join a skete or become a solitary; most monastics remain in the cenobium the whole of their lives. The form of monastic life an individual embraces is considered to be his vocation; that is to say, it is dependent upon the will of God, and is revealed by grace.

From a religious point of view, the solitary life is a form of asceticism, wherein the hermit renounces worldly concerns and pleasures in order to come closer to the deity or deities they worship or revere. This practice appears also in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Sufism.[1] In the ascetic eremitic life, the hermit seeks solitude for meditation, contemplation, and prayer without the distractions of contact with human society, sex, or the need to maintain socially acceptable standards of cleanliness or dress. The ascetic discipline can also include a simplified diet and/or manual labor as a means of support.

Mendicant orders

"Mendicant orders" are religious orders which depend directly on begging, or the charity of the people for their livelihood. In principle they do not own property, either individually or collectively, and have taken a vow of poverty, in order that all their time and energy could be expended on religious work.

Christian mendicant orders spend their time preaching the Gospel and serving the poor. In the Middle Ages, the original mendicant orders of friars in the Church were the

- Franciscans (Friars Minor, commonly known as the Grey Friars), founded 1209

- Carmelites, (Brothers of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Carmel, commonly known as the White Friars), founded 1206–1214

- Dominicans (Order of Preachers, commonly called the Black Friars), founded 1215

- Augustinians (Hermits of Saint Augustine, commonly called the Austin Friars), founded 1256

The Second Council of Lyons (1274) recognized these as the four "great" mendicant orders, and suppressed certain others. The Council of Trent loosened their property restrictions.

Among other orders are the:

- Discalced Carmelites

- Trinitarians (Order of the Most Blessed Trinity), founded 1193

- Mercedarians (Order of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mercy), founded 1218

- Servites (Order of Servants of Mary), founded 1233

- Minims (Hermits of Saint Francis of Paola), founded 1436

- Capuchins (Order of Friars Minor Capuchin), established 1525

- Brotherhood of Saint Gregory (an Anglican order) founded 1969

Monks in Different Religions

Judaism

The existence of ascetic individuals and groups in Judaism preceeds the rise of Christianity as an organized religion. Jewish groups such as the Essenes and the Nazirites, were famous for their monastic discipline, as were the Therapeutae of ancient Egypt. The New Testament itself, describes the ascetic behavior of John the Baptist who lived in the wilderness, a forerunner of Christian monasticism.

The term monastery was used by the Jewish philosopher Philo (c. 20 B.C.E. - 50 C.E., resident in Alexandria, Egypt) in his description of the life of the Therapeutae and Therapeutides, people with common religious aspirations who then were dwelling on a low-lying hill above the Mareotic Lake near Alexandria in houses at a distance of each other that safeguarded both solitude and security [2]

In each house there is a consecrated room which is called a sanctuary or closet (monastērion), and closeted (monoumenoi) in this they are initiated into the mysteries of the sanctified life. They take nothing into it, either drink or food or any other of the things necessary for the needs of the body, but laws and oracles delivered through the mouth of prophets, and hymns and anything else which fosters and perfects knowledge and piety. They keep the memory of God alive and never forget it … Twice every day they pray, at dawn and at eventide … The interval between early morning and evening is spent entirely in spiritual exercise. They read the holy scriptures and seek wisdom from their ancestral philosophy … For six days they seek wisdom by themselves in solitude in the closets (monastēriois) mentioned above … But every seventh day they meet together as for a general assembly … (in a) common sanctuary.[3]

Christianity

Monasticism drew its origin from the examples of the Prophet Elijah and John the Baptist who both lived alone in the desert. Jesus himself dwelt in solitude in the desert for forty days, and the Gospels record other times in which he retired for periods of solitary prayer. In the early church, individuals would live ascetic lives, though usually on the outskirts of civilization. Communities of virgins are also mentioned by early church authors, but again these communities were either located in towns, or near the edges of them.

The first famous Christian known to adopt the life in a desert was Saint Anthony of Egypt (251-356 C.E.). He lived alone as an anchorite in the Egyptian desert until he attracted a circle of followers, after which he retired further into the desert to escape the adulation of people. In his early practice, Saint Anthony lived near the town and had an experienced ascetic give him advice; later, he went out into the desert for the sole purpose of pursuing God in solitude. As the idea of devoting one's entire life to God grew, more and more monks joined him, even in the far desert. Under St. Anthony's system, they each lived in isolation. Later, loose-knit communities began to be formed, coming together only on Sundays and major feast days for Holy Communion. These are referred to as sketes, named after the location in Egypt where this system began. The concept of monks all living together under one roof and under the rule of a single abbot is attributed to St. Pachomios (ca. 292 - 348), who lived in the beginning of the fourth century, and is referred to as coenobitic monasticism. At this same time, Saint Pachomios' sister became the first abbess of a monastery of women (convent). Christian monasticism spread throughout the Eastern Roman Empire. At its height it was not uncommon for coenobitic monasteries to house upwards of 30,000 monks.

As Christianity grew and diversified, so did the style of monasticism. In the East, monastic norms came to be regularized through the writings of St. Basil the Great (c. 330 - 379) and St. Theodore the Studite (c. 758 - c. 826), coalescing more or less into the form in which it is still found today. In the West, there was initially some distrust of monasticism, due to fears of extremism previously observed in certain heretical groups, most notably Gnosticism. Largely through the writings of St. John Cassian (c. 360 – 433), monasticism came to be accepted in the West as well. Saint Benedict of Nursia (c. 480 – 547) set forth an early monastic rule in the west. In the beginning, Western monasticism followed much the same pattern as its Eastern forebears, but over time the traditions diversified.

Monks in Eastern Orthodoxy

In the Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Churches, monasticism still holds a very special and important place. Far more common than in the Roman Catholic Church, the spiritual health of the Orthodox Church can be measured by the quality of its monks and nuns. Orthodox monastics separate themselves from the world in order to pray unceasingly for the world. They do not, in general, have as their primary purpose the running of social services, as is common in Western Christianity, but instead are concerned with attaining [[theosis], or union with God. However, caring for the poor and the needy have always been an obligation of monasticism. Orthodox monasteries are not normally "cloistered," though the level of contact will vary from community to community. Orthodox hermits, on the other hand, have little or no contact with the outside world.

Orthodox monasticism does not have religious orders as are found in the West, nor do they have Rules in the same sense as the Rule of Saint Benedict. Rather, Eastern monastics study and draw inspiration from the writings of the Desert Fathers as well as other Church Fathers; probably the most influential of which are the Greater Asketikon and Lesser Asketikon of Saint Basil the Great and the Philokalia, which was compiled by Saint Nikodemos of the Holy Mountain and Saint Makarios of Corinth. Hesychasm is of primary importance in the ascetical theology of the Orthodox Church.

Most communities are self-supporting, and the monastic’s daily life is usually divided into three parts: (a) communal worship in the catholicon (the monastery's main church); (b) hard manual labour; and (c) private prayer, spiritual study, and rest when necessary. Meals are usually taken in common in a sizable dining hall known as a trapeza (refectory), at elongated refectory tables. Food is usually simple and is eaten in silence while one of the brethren reads aloud from the spiritual writings of the Holy Fathers. The monastic lifestyle takes a great deal of serious commitment and hard work. Within the coenobitic community, all monks conform to a common way of living based on the traditions of that particular monastery. In struggling to attain this conformity, the monastic comes to realize his own shortcomings and is guided by his spiritual father in how to deal honestly with them. Attaining this level of self-discipline is perhaps the most difficult and painful accomplishment any human being can make; but the end goal, to become like an angel on earth (an "earthly angel and a heavenly man," as the church hymns put it), is the reason monastics are held in such high esteem. For this same reason, Bishops are almost always chosen from the ranks of monks.

In general, Orthodox monastics have little or no contact with the outside world, including their own families. The purpose of the monastic life is union with God, the means is through leaving the world (i.e., the life of the passions). After tonsure, Orthodox monks and nuns are never permitted to cut their hair. The hair of the head and the beard remain uncut as a symbol of the vows they have taken, reminiscent of the Nazarites from the Old Testament. The Tonsure of monks is the token of a consecrated life, and symbolizes the cutting off of their self-will.

The process of becoming a monk is intentionally slow, as the vows taken are considered to entail a life-long commitment to God, and are not to be entered into lightly. In Orthodox monasticism after completing the novitiate, there are three ranks of monasticism. There is only one monastic habit in the Eastern Church (with certain slight regional variations), and it is the same for both monks and nuns. Each successive grade is given a portion of the habit, the full habit being worn only by those in the highest grade, known for that reason as the "Great Schema," or "Great Habit." One is free to enter any monastery of one's choice; but after being accepted by the abbot (or abbess) and making vows, one may not move from place to place without the blessing of one's ecclesiastical superior.

- Novice (Slavonic: Poslushnik), lit. "one under obedience"—Those wishing to join a monastery begin their lives as novices. He is also given a prayer rope and instructed in the use of the Jesus Prayer. If a novice chooses to leave during the period of the novitiate, no penalty is incurred. He may also be asked to leave at any time if his behaviour does not conform to the monastic life, or if the superior discerns that he is not called to monasticism. When the abbot or abbess deems the novice ready, he is asked if he wishes to join the monastery. Some, out of humility, will choose to remain novices all their lives. Every stage of the monastic life must be entered into voluntarily.

- Rassaphore, (Slavonic: Ryassophore), lit. "Robe-bearer"—If the novice continues on to become a monk, he is clothed in the first degree of monasticism at a formal service known as the Tonsure. Although there are no formal vows made at this point, the candidate is normally required to affirm his commitment to persevere in the monastic life. The abbot will then perform the tonsure, cutting a small amount of hair from four spots on the head, forming a cross. He is then given the outer cassock (Greek: Rasson, Exorasson, or Mandorrason; Slavonic: Riassa)—an outer robe with wide sleeves, something like the cowl used in the West, but without a hood—from which the name of Rassaphore is derived. He is also given a brimless hat with a veil, known as a klobuk, and a leather belt is fastened around his waist. His habit is usually black, signifying that he is now dead to the world, and he receives a new name. Although the Rassaphore does not make formal vows, he is still morally obligated to continue in the monastic estate for the rest of his life. Some will remain Rassaphores permanently without going on to the higher degrees.

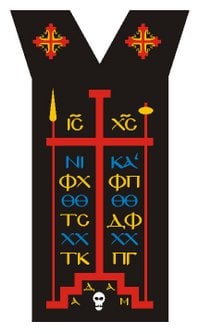

- Stavrophore, (Slavonic: Krestonosets), lit. "Cross-bearer"—The next level for Eastern monastics takes place some years after the first tonsure when the abbot feels the monk has reached an appropriate level of discipline, dedication, and humility. This degree is also known as the Little Schema, and is considered to be a "betrothal" to the Great Schema. At this stage, the monk makes formal vows of stability, chastity, obedience and poverty. Then he is tonsured and clothed in the habit, which in addition to that worn by the Rassaphore, includes the paramandyas (Slavonic: paraman), a piece of square cloth worn on the back, embroidered with the instruments of the Passion, and connected by ties to a wooden cross worn over the heart. The paramandyas represents the yoke of Christ. Because of this addition he is now called Stavrophore, or Cross-bearer. He is also given a wooden hand cross (or "profession cross"), which he should keep in his icon corner, and a beeswax candle, symbolic of monastic vigilance the sacrificing of himself for God. He will be buried holding the cross, and the candle will be burned at his funeral. In the Slavic practice, the Stavrophore also wears the monastic mantle. The rasson (outer robe) worn by the Stavrophore is more ample than that worn by the Rassaphore. The abbot increases the Stavrophore monk’s prayer rule, allows a more strict personal ascetic practice, and gives the monk more responsibility.

- Great Schema (Greek: Megaloschemos, Slavonic: Skhimnik)—Monks whose abbot feels they have reached a high level of spiritual excellence reach the final stage, called the Great Schema. The tonsure of a Schemamonk follows the same format as the Stavrophore, and he makes the same vows and is tonsured in the same manner. But in addition to all the garments worn by the Stavrophore, he is given the Analavos (Slavonic: Analav) which is the article of monastic vesture emblematic of the Great Schema. For this reason, the analavos itself is sometimes called the "Great Schema" (see picture above). The analavos comes down in the front and the back, somewhat like the scapular in Western monasticism, although the two garments are probably not related. It is often intricately embroidered with the instruments of the Passion and the Trisagio (the angelic hymn). The Greek form does not have a hood, the Slavic form has a hood and lappets on the shoulders, so that the garment forms a large cross covering the monk's shoulders, chest, and back. In some monastic traditions the Great Schema is only given to monks and nuns on their death bed, while in others they may be elevated after as little as 25 years of service.

Eastern Orthodox monks are addressed as "Father" even if they are not priests; but when conversing among themselves, monks will often address one another as "Brother." Novices are always referred to as "Brother." Among the Greeks, old monks are often called Gheronda, or "Elder," out of respect for their dedication. In the Slavic tradition, the title of Elder (Slavonic: Starets) is normally reserved for those who are of an advanced spiritual life, and who serve a guides to others.

For the Orthodox, Mother is the correct term for nuns who have been tonsured Stavrophore or higher. Novices and Rassophores are addressed as "Sister." Nuns live identical ascetic lives to their male counterparts and are therefore also called monachai (the feminine plural of monachos), and their community is likewise called a monastery.

Many (but not all) Orthodox seminaries are attached to monasteries, combining academic preparation for ordination with participation in the community's life of prayer, and hopefully benefiting from the example and wise counsel of the monks. Bishops are required by the sacred canons of the Orthodox Church to be chosen from among the monastic clergy. It should be noted that the requirement is specifically that they be monastics, not simply celibate. Monks who have been ordained to the priesthood are called hieromonks (priest-monks); monks who have been ordained to the diaconate are called hierodeacons (deacon-monks). A Schemamonk who is a priest is called a Hieroschemamonk. Most monks are not ordained; a community will normally only present as many candidates for ordination to the bishop as the liturgical needs of the community require.

Monks in Western Christianity

The religious vows taken in the West were first developed by Saint Benedict of Nursia (c. 480- c. 547) who wrote the Rule of Saint Benedict. These vows were three in number: obedience, conversion of life, and stability. Among later Western religious orders, these developed into the solemn vows of obedience, poverty, and chastity.

To become a monk, one had to first become an oblate or a novice. To become an oblate, one had to be given to the monastery by one's father. Then, if one was old enough, one could take their first vows and become a novice. After several years, if the abbot (head of the monastery) allowed, one could then become a monk.

The monks in the Middle Ages lived in a monastery, similar to a modern boarding school. Most monasteries were shaped like a cross so they would remember Jesus Christ, who died on a cross. The monastery had three vows: obedience, chastity, and poverty, which made up the evangelical counsels. Obedience meant that monks were willing to obey the Catholic Church, as represented by the abbot (head of the monastery), chastity meant that since they were willing to dedicate their lives to God, they would not marry; poverty meant they lived their lives of sharing, and shared all their possessions within the community and for the poor and would not hold back for themselves.

Monks grew their own food and shared their work in the monastery. Some of the more qualified monks were set to more challenging tasks, while others did mundane work according to their abilities. The monks spent on average about seven hours a day on work, except for Sunday, which was the day of rest.

Monks wore a plain brown or black cape and a cross on a chain around their neck; underneath, they wore a hair shirt to remind themselves of the suffering Christ had undergone for them. A man became a monk when he felt a call to God and when he wanted to dedicate his life in God's service and gain knowledge of God. There could be other reasons individuals felt called into the monastery, such as wanting to be educated, as the monasteries were at one time some of the few places in the world where one was taught to read and write.

The monks called each other "brother" to symbolize their new brotherhood within their spiritual family. The monasteries usually had a strict timetable according to which they were required to adhere. They grew their food for themselves and ate it in complete silence. The monks were not allowed to talk to each other anywhere, except in very special places. The monks also sometimes had hospitals for the sick.

Anglicanism also has its own religious orders of monks. There are Anglican Benedictines, Franciscans, Cistercians, and, in the Episcopal Church in the USA, Dominicans), as well as home grown orders such as the Society of Saint John the Evangelist, among others.

An important aspect of Anglican religious life is that most communities of both men and women lived their lives consecrated to God under the vows of poverty, chastity and obedience (or in Benedictine communities, Stability, Conversion of Life, and Obedience) by practicing a mixed life of reciting the full eight services of the Breviary in choir, along with a daily Eucharist, plus service to the poor.

Anglican monks proceed through their religious life first by responding to an inner call to the particular life. Then after counseling with his parish priest, the seeker makes a visit to a monastery and tests his vocation. Usually he must spend some time with the community as an aspirant, then he becomes a postulant, then novice, then come first profession, and usually life vows.

Some communities are contemplative, some active, but a distinguishing feature of the monastic life among Anglicans is that most practice the so-called "mixed life." They keep the full round of liturgical and private worship, but also usually have an active ministry of some sort in their immediate community. This activity could be anything from parish work to working with the homeless, retreats or any number of good causes. The mixed life, combining aspects of the contemplative orders and the active orders remains to this day a hallmark of Anglican religious life.

Since the 1960s, there has been a sharp falling off in the numbers of monks in many parts of the Anglican Communion. Many once large and international communities have been reduced to a single convent or monastery comprised of elderly men or women. In the last few decades of the twentieth century, novices have for most communities been few and far between. Some orders and communities have already become extinct.

There are however, still several thousand Anglican monks working today in approximately 200 communities around the world.

The most surprising growth has been in the Melanesian countries of the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu and Papua New Guinea. The Melanesian Brotherhood, founded at Tabalia, Guadalcanal, in 1925 by Ini Kopuria, is now the largest Anglican Community in the world with over 450 brothers in the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines and the United Kingdom. Furthermore, the Sisters of the Church, started by Mother Emily Ayckbown in England in 1870, has more sisters in the Solomons than all their other communities. The Community of the Sisters of Melanesia, started in 1980 by Sister Nesta Tiboe, is a growing community of women throughout the Solomon Islands. The Society of Saint Francis, founded as a union of various Franciscan orders in the 1920s, has experienced great growth in the Solomon Islands. Other communities of religious have been started by Anglicans in Papua New Guinea and in Vanuatu. Most Melanesian Anglican religious are in their early to mid-twenties, making the average age 40 to 50 years younger than their brothers and sisters in other countries. This growth is especially surprising because celibacy was not traditionally regarded as a virtue in Melanesia.

Another important development in Anglican monasticism is religious communities that allow both single and married people interested in the monastic lifestyle to become first order monks and nuns. An example of this is the Cistercian Order of the Holy Cross [4] an Order in full Anglican Communion with a traditional period of postulancy and noviceship for applicants in the Roman, Anglican or Orthodox faith traditions.

Buddhism

Although the European term "monk" is often applied to Buddhism, the situation of Buddhist asceticism is different.

In Theravada Buddhism, bhikkhu is the term for monk. Their disciplinary code is called the patimokkha, which is part of the larger Vinaya. They live lives of mendicancy, and go on a morning almsround (Pali: pindapata) every day. The local people give food for the monks to eat, though the monks are not permitted to positively ask for anything. The monks live in wats (monasteries), and have an important function in traditional Asian society. Young boys can be ordained as samaneras. Both bhikkhus and samaneras eat only in the morning, and are not supposed to lead a luxurious life. Their rules forbid the use of money, although this rule is nowadays not kept by all monks. The monks are part of the Sangha, the third of the Triple Gem of Buddha, Dhamma, Sangha. In Thailand, it is common for most every boy to spend some time living as a monk in a monastery. Most stay for only a few years and then leave, but a number continue on in the ascetic life for the rest of their lives.

In Vajrayana Buddhism, monkhood is part of the system of 'vows of individual liberation'; these vows are taken in order to develop one's own personal ethical discipline. The monks and nuns form the (ordinary) sangha. As for the Vajrayana vows of individual liberation, there are four steps: A lay person may take the 5 vows called 'approaching virtue' (in Tibetan 'genyen' <dge snyan>). The next step is to enter the monastic way of life (Tib. rabjung) which includes wearing monastic robes. After that, one can become a 'novice' (Pali samanera, Tib. getshül); the last and final step is to take all vows of the 'fully ordained monk' (gelong). This term 'gelong' (Tib. <dge long>, in the female form gelongma) is the translation of Sanskritt bikshu (for women bikshuni) which is the equivalent of the Pali term bhikkhuni; bhikkhu is the word used in Theravada Buddhism.

Chinese Buddhist monks have been traditionally linked with the practice of the Chinese martial arts or Kung fu, and monks are frequently important characters in martial arts films. This association is focused around the Shaolin Monastery. The Buddhist monk Bodhidharma, traditionally credited as the founder of Zen Buddhism in China, is also claimed to have introduced Kung fu to the country. This latter claim has however been a source of much controversy.

Hinduism

In Hinduism, the terms Sadhu, Swami and Sannyasi refer to renunciates and spiritual masters, who have usually left behind all material attachments to live in forests, temples and caves all over India. The word "Sadhu" is the general term for a Hindu ascetic who has given up the pursuit of the first three Hindu goals of life: kama (pleasure), artha (wealth and power) and even dharma (duty), to solely dedicate himself to achieving moksha (liberation) through meditation and contemplation of God. The title Swami literally translates as "owner of oneself," denoting complete mastery over instinctive and lower urges. Many yogis and gurus (teachers) of the Hindu tradition hold the title of Swami as a sign of respect denoting spiritual accomplishment.

Holy men and women have long played an important role in Indian culture and religious traditions. As a result, there are a variety of Hindu terms used to denote religious mendicants. The most famous terms are "Yogis" (those who practice Yoga), "Gurus" (those who dispel spiritual darkness), "Sadhus" (medicants), "Swamis" (Spiritual Masters), "Rishis" (Seers), and "Sannyasis" (Renunciates). The number of these terms is a sign of the importance of holy men and women in Indian life even today.

Sadhus and Swamis occupy a unique and important place in Hindu society. Vedic textual data suggests that asceticism in India - in forms similar to that practiced by sadhus today - dates back to 1700 B.C.E. Thus, the present-day sadhus of India likely represent the oldest continuous tradition of monastic mystical practice in the world.

Traditionally, becoming a Sannyasi or Sadhu was the fourth and highest stage (asrama) in life in classical Hinduism when men, usually over sixty, would renounce the world, undergoing a ritual death (and symbolic rebirth), in the pursuit of moksha. At least three preconditions needed to be fulfilled before one could take this vow of renunciation- one needed to have completed one's duties to family and ancestors, one's hair should have turned gray, and one should have ensured a grandson to continue the obligatory family rituals.

It is estimated that there are several million sadhus in India today. Along with bestowing religious instruction and blessings to lay people, sadhus are often called upon to adjudicate disputes between individuals or to intervene in conflicts within families. Sadhus are also considered to be living embodiments of the divine, and images of what human life, in the Hindu view, is truly about - religious illumination and liberation from the cycle of birth and death (Samsara). It is also thought that the austere practices of the sadhus help to burn off their karma and that of the community at large. Thus seen as benefiting society, many people help support sadhus with donations. Thus, by and large, sadhus are still widely respected, revered and even feared, especially for their curses. However, reverence of sadhus in India is by no means universal. Indeed, sadhus have often been seen with a certain degree of suspicion, particularly amongst the urban populations of India. In popular pilgrimage cities, posing as a 'sadhu' can be a means of acquiring income for beggars who could hardly be considered 'devout.' Some sadhus fake holy status to gain respect but they are normally discovered by true sadhus.

Madhvaacharya (Madhva), the Dvaita Vedanta philosopher, established ashta matha (Eight Monastries). He appointed a monk (called swamiji or swamigalu in local parlance) for each matha or monastery who has the right to worship Lord Krishna by rotation. Each matha's swamiji gets a chance to worship after fourteen years. This ritual is called Paryaya.

Monks from the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), or Hare Krishnas as they are popularly known, are the best known Vaishnava monks outside India. They are a common sight in many places around the world. Their appearance—simple saffron dhoti, shaved head with sikha, Tulasi neckbeads and tilaka markings—and social customs (sadhana) date back many thousands of years to the Vedic era. ISKCON started as a predominantly monastic group but nowadays the majority of its members live as lay persons. Many of them, however, spent some time as monks. New persons joining ISKCON as full-time members (living in its centers) first undergo a three-month Bhakta training, which includes learning the basics of brahmacari (monastic) life. After that they can decide if they prefer to continue as monks or as married Grihasthas. A Brahmachari older than fifty years can become sannyasi, which is a permanent decision that one cannot give up.

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dietz, Maribel. Wandering Monks, Virgins, And Pilgrims: Ascetic Travel In The Mediterranean World, A.D. 300-800. Pennsylvania State University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0271026770

- Farmer, Sharon, & Barbara H. Rosenwein. Monks and Nuns, Saints and Outcasts: Religion in Medieval Society. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0801486562

- Harmless, William. Desert Christians: An Introduction to the Literature of Early Monasticism. Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0195162233

- Kiser, John. "The Monks of Tibhirine: Faith, Love, and Terror in Algeria" St. Martin's Griffin, 2003. ISBN 978-0312302948

- Porter, Bill. Road to Heaven: Encounters With Chinese Hermits. Mercury House, 1993. ISBN 978-1562790417

- Seward, Desmond. The Monks of War: The Military Religious Orders. Penguin (Non-Classics), 1996. ISBN 978-0140195019

- Ward, Benedicta. "The Desert Fathers: Sayings of the Early Christian Monks. Penguin Classics, 2003. ISBN 978-0140447316

External links

All links retrieved June 1, 2025.

- Monk Catholic Encyclopedia

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.