Temple

A Temple (from the Latin: templum "sacred place") is a house of worship used primarily for the purposes of religious devotion. Temples serve a variety of functions in the lives of a religious community: as places for ritual, worship, celebration, sacrifice, and communal activity. Most religions have temples of some sort, whether they are termed "mosque," "mandir," "church," or "gurdwara." Temples are an essential part of many religious traditions because they are believed to represent a physical location for connecting with the divine. In addition, ancient temples frequently functioned as a social center, like a City Hall with scribes and record keepers. Sometimes they were a place of refuge and care for widows, orphans, the handicapped, the sick, and refugees from war.[1] There was no separation of religion and state in the ancient world.

The various temples of the world exhibit a vast array of architectural and iconographic styles. However, they share the same common interest in creating a "sacred space" in which to commune with the divine. This theme is so central to human religiosity that virtually all religions (even those who do not use temples) make use of the metaphorical connotations of the term, as it provides a symbol that can be utilized both macrocosmically (viewing the entire universe as a temple of God) and microcosmically (viewing one's own body as a temple of divine energy, power, and love).

Historical Origins of Temples

In exploring the archaeological remains of various pre-literate cultures, it appears that the practice of worship in temples developed concurrently in various locations around the world. As a result of this contemporaneous development, which was deemed far too significant to be a mere coincidence, scholars of religion developed a hypothetical timeline to account for it.

They argue, based on archaeological evidence, that many early cultures were fascinated with the appearance of constellations and stars in the sky, which motivated them to conduct worship rituals under the firmament, at open-air altars. Over time, it is thought that these early religious adherents began to construct physical structures that emulated the sacred geometry seen in the constellations and other majestic natural phenomena. This allowed them to re-create (through architecture and symbol) the sense of sacredness that they experienced in nature. For example, temples in India and Southeast Asia were often designed in the form of sacred mandalas representing the cosmos, and, likewise, Egyptian and Meso-American temples were often oriented and aligned with the positions of various stars and planets. In a similar manner, the early Israelites felt it necessary to construct a massive temple (whose measurements were numerically tied to their cosmological views) as a fitting place to house the Ark of the Covenant. In all of the above cases, the temples were constructed to create a sacred space within which the religious adherents believed they could commune with the Divine. This understanding is congruent with many approaches taken in modern religious studies: it centers on the an understanding of sacred space (as per Mircea Eliade), of the Holy as a possible motivator of human action (as per Rudolf Otto), and of the human tendency to explore the world through metaphors and symbols (as per Susanne Langer, Michel Foucault, and other semioticians).

Despite the common function of temples as a representation of sacred space, it is also true that the temples of different religious traditions do have their own distinctive characteristics. To explore this more fully, a cross-section of temples from various cultures is presented below.

Temples of the Mediterranean and Near East

Egyptian Temples

Egyptian temple practice, characterized by monumental construction and involved rituals, flourished from the period of the Old Kingdom (third millennium B.C.E.) into the period of Roman rule. Their traditions were so well-established that even foreign occupiers (prior to the Christian period) did not impose their temple designs on Egypt.

Architecturally, Egyptian temples were laid out along an axis, beginning at a gate, flanked by towers, proceeding inward to the central shrine that housed an image of the deity to which the temple was dedicated. On either side of the central axis were rooms for storage of sacred items and administration of the temple. Progressing inward toward the shrine, the level of the floor was gradually graded upward. Also, the height of the ceiling steadily decreased, resulting in an ever shrinking passage, suggestive of a rising of the earth and the lowering of the heavens. The entire complex was surrounded by high walls.

Ritual was of seminal importance to Egyptian religion, and accordingly was central to the function of the temple. The main shrine that housed the image of the deity was considered a home for the deity, and rituals performed therein were done so for the benefit of the deity. As such, the main shrine was seen as being a highly sacred space, making it solely the domain of the priests and rendering it unavailable to the average devotee. These rituals, which included sacrifices and prayers, were performed daily. However, at various significant times during the year (especially the beginning of flood season), temple processions carried the divine images and special ceremonial boats from the interior of the temple to the exterior, involving the average person in worship.

Greek and Roman Temples

Greek temples, a staple of Western art and lore, actually share some notable architectural similarities with Egyptian temples, especially the use of multiple columns and the masonry used in construction. However, Classical and Hellenistic Greek temples are distinguished by their layouts: single rectangular rooms housing images, adorned with ornate columns, built with a porch at the entrance, and containing an altar for sacrifice. As the temples were often associated with specific festivals, they were oriented so their entrances would face the rising sun on the day of the festival. The style of their columns, one of the most characteristic features of these structures, depended upon the region where the temple built. Finally, the particular deity housed in the temple was chosen based upon the needs/interests of the worship community (for example, Athens contained numerous temples to Athena (its patron deity), while rural areas were more likely to have temples dedicated to Demeter or Dionysius).

Though similarities exist between the construction of Egyptian and Greek temples, they differ markedly in their respective functions. While Egyptian temple worship was exclusively performed by priests, Greek worship involved communal participation. Their temples were laid out with the sacrificial altar placed between the divine statue and the public area, which allowed both the spectators and the effigy of the deity to watch the sacrifices being performed.

Just as Roman religion was largely derived from Greek religion, Roman temples adopted Hellenistic styles, though they maintained the high bases and single set of steps of their Etruscan neighbors. Unlike the Greek styles, the Romans would rarely surround their temples with columns, often only adorning the facade in this manner. The Roman style allowed for circular temples, like the Pantheon in Rome. Roman temples were important for religious festivals, but could serve as secular buildings when necessary.

The Israelite Temples

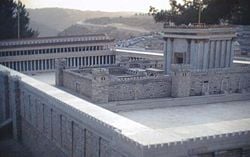

Though temples throughout ancient Israel are recorded in the Hebrew Bible and found at archaeological sites, the most significant temples were the First and Second Temples of Jerusalem. The former is dated 960 B.C.E.–950 B.C.E. to its destruction by the Babylonians in 587 B.C.E.–586 B.C.E., whereas the latter is dated 516 B.C.E. to 70 C.E.

The First Temple, built during the reign of King Solomon, was an elliptical structure made of stone and cedar. It had a courtyard at its entrance, with an altar for burnt offerings. Inside, the temple was divided into two sections. The first, nearest the entrance, was the Great Hall. Within the hall was an incense altar. The more important room, entered after passing through the Great Hall, was the shrine, called the Holy of Holies. Within the shrine was placed the Ark of the Covenant, the final resting place for the tablets of law given to Moses at Mount Sinai. This room was built upon an enormous rock, called the "foundation stone." The inside of the temple was planked with cedar and decorated with gold. The temple also had various storehouses, where the items used for worship were housed (1 Kings 6:2-38). Though the temple was originally constructed along biblical guidelines, various embellishments and renovations were made over the centuries, often in accord with political situations.

The Second Temple, built after the Babylonian Exile, was erected upon the same site as the former temple and used a similar plan as the first, though it was more impressive in size. The shrine, however, no longer contained the Ark of the Covenant though it still was considered the dwelling place of the God of Israel. Like the first temple, the new temple would see a number of renovations, most importantly under the Hasmoneans and Herod. In the Second Temple period some of the rituals, like the enthronement hymns to Yahweh, bore similarities to ceremonies of the enthronement of Marduk in Babylon.[2]

A fairly clear understanding of Israelite temple practice can be gleaned from the books of Exodus, Leviticus, and Numbers. Worship was focused on sacrifice, which was performed during the day, at dusk, and on important occasions such as festivals. The book of Leveticus also contains highly specific procedural guidelines for atonement offerings, which provide an example of private ritual. Sacrifices took many forms: livestock, grains, produce, and currency. Livestock, such as cattle or sheep, were often sacrificed as burnt offerings. Those parts not burned (if any, dependent on the ritual) would be cooked and eaten by donors and priests. First fruits and harvests were common offerings. Also, wheat flour (turned to dough through mixing with oils) was also burned and eaten. Prayers and songs accompanied sacrifice.

Due to the centrality of the temple for all of these sacrificial and ritual purposes, its destruction promoted an intense crisis of faith for the early Jews. To answer this crisis, the Rabbis, the scholarly class who founded modern Judaism, suggested that the temple be internalized by each believer—thus making every action and thought a sacrifice to the Almighty.

Temples in India

Hindu Temples

Though they were predated by various Aryan and Dravidian worship structures, the first recognizably Hindu temples can be traced back to the fifth century C.E. The precursors to these were shrines set up around important objects, such as trees, lingas, and other sacred items. These sites were often fairly open and were enclosed by railings or gates. When Hindu temples did begin to appear in India, they were easily differentiated due to their stone constructions and more substantial structures. However, the role they played was similar to the function of the earlier shrines: to house a focal point for worship and ritual.

The central element of the Hindu temple is the image of the deity, and the fundamental function of the temple is to serve as a location for ritual worship (puja) and communion with the divine (darshan). Hindu temples are also venues for religious dance and music, which take place in assembly halls within the temple complex. Important forms of bhakti (religious devotion) that are practiced in Hindu temples involve approaching, prayer to, meditating upon, and circumambulating the divine image. Most often the major entrance to the temple is the eastern gate, facing the sunrise, though often there are gates on all sides. The approach from the entrance to the image along the major axis is meant to represent an ascent to the sanctuary and to convey a sense of mystery to the worshiper.

Though much variety exists in Hindu temple construction, there are certain common principles. An important text relating to the construction of temples (and other structures) is the Brhat Samhita, written in the sixth century C.E. by Varahamihira. Temple layout is inspired by creation mythology, recounting the story of the first sacrifice of Vastupurusha, who was dismembered by devas to create the world. The plan is an eight square by eight square mandala (sixty-four squares total), the four central squares dedicated to Brahman, while other sections of the plan are dedicated to Indra, Agni, and other members of the Hindu pantheon. In this way the Hindu temple is a monument to, and constant reminder of, creation—a visual and spatial allusion to Vastupurusha. Also, the central place of Brahman, serving as the point from which the temple extends in the four cardinal directions, attests to Brahman's pivotal role in creation within the (largely monistic) Hindu cosmology.

The sanctuary of the temple that houses the image of the deity is meant to represent a womb, which is simultaneously a symbol of divine power and potential. Hindu temple complexes in Northern India (such as Khojaharo, for example) often resemble mountains as symbols of strength and endurance.

Southern Indian temples (also known as Dravidian Temples) had their own unique style contrasting with the north. Rather than appearing as a monolithic towering structures resembling mountains, Dravidian Temples utilized massive gateways (called Gopurams), covered with a multiplicity of divine imagery, as entry points leading to middle of the temple where the central shrine was kept in a modest and smaller building. Some of these southern temples are fortress-like in appearance, a fact that is also capitalized upon by the designers, for just as the temple is a reminder of creation, it is also a defense against the dangers of chaos.

Buddhist Temples

Early sites of importance in Buddhism were not buildings, but physical places of significance in the early history of Buddhism (e.g. Bodhgaya, where the Buddha attained enlightenment, Lambini, where he was born, and Sarnath, where he gave his first sermon). After the death of the Buddha, stupas (sacred mounds) were built to house relics or mark special locations. Originally few in number and quite modest, stupa building became a passion for the religious king Asoka, who re-distributed Buddhist relics as part of a large-scale proselytizing effort. In general, though, stupa construction was not only the domain of rulers and many stupas were built by the Buddhist sangha and devoted laity.

Early Buddhists were not concerned with the worship of the Buddha during activities at the stupa complex, choosing instead to use the stupa as a lens to focus on important Buddhist teachings. Likewise, the stupa itself, due to its characteristic shape, symbolized the "cosmic egg," a principal idea in Buddhist creation mythology and cosmology. Over time it was recognized that the stupa, being of primary importance to religious adherents, needed to be protected from the elements, which eventually led to the construction of large shelters and temple complexes around these shrines. These complexes would also house wandering monks and pilgrims in simple cells that were built directly into the temples. As in other traditions, Buddhist temples grew in size and complexity over time, gradually becoming massive complexes (like the Indonesian Shrine at Borobudur).

As Mahayana Buddhism developed (with its acceptance of worship practices directed at the Buddha and the introduction of other salvific figures known as Bodhisattvas), religious iconography became a more common element of Buddhist practice. These images would be housed within the temple complex, sometimes being placed within the stupa itself.

Temples in Asia

Chinese Temples

Temples in China share a large number of common characteristics, whether they are Buddhist, Daoist, Confucian, or associated with a folk tradition. Much like the overall Chinese approach to spirituality, the differences between the religious structures used by these religious traditions is often not emphasized. For example, the various temples cannot be distinguished based on the materials from which they are built, as virtually all Chinese temples are made of timber (in Southern China) or timber and brick (in Northern China). Indeed, even secular buildings are composed of similar materials. However, though it can be said that all the Chinese religions share a common temple style, each one does have its own particular nuances.

Chinese temple complexes are often arranged in similar ways. Typically, large halls are separated and surrounded by pavilions, and the entire complex is then surrounded by a wall, with an especially elaborate gate at the entrance. The main entrances to all temples in China is situated at the south end of the complex in accordance with the principles of feng shui. It is thought that evil spirits enter from the north, thus a southern entrance limits their access. However, for practical reasons, smaller gates are usually found on most or all sides of larger temple complexes. Since the main entrance is at the southernmost part of the temple complex, the main hall of the temple is often located at the northernmost part, thus orienting the entire construction on a north-south axis. Lesser halls are often situated on the west or east side of the major axis, with their entrances oriented towards the center axis.

The decoration of temples follows a near-universal scheme. The most prevalent color is red (which symbolizes prosperity and good fortune), with green and gold used as accents. Likewise, common iconographic themes are also shared, regardless of the temple's affiliation. Some of these include signs of the Chinese zodiac, elaborate mythological creatures (dragons, phoenixes, etc.) and characters written in calligraphic script. Though the central images differ based on the affiliation of the temple, the placement of these images within the various halls and pavilions is quite consistent, with various statues displayed in places of prominence. In the open courtyards, one often finds incense burners, which are used to make offerings to the deities represented in the halls.

Temples in China are used primarily for offering ritual gifts and devotion to the various Chinese deities or Buddhist bodhisattvas. This practice often involves chanting, prostration, and the burning of incense. Temples may also be the site of religious festivities, involving rituals, music, and dancing. As well, temples may have living compounds to house monks and nuns that work at the temple. Historically, some temples (especially the Temple of Heaven in modern Beijing) had particular socio-political importance, as they were central to the imperial cult. For example, the Temple of Heaven was used by the emperor to perform sacrifices and to pray to Heaven for a productive harvest season.

Buddhist Temples

A great deal of Buddhist temple architecture in China was derived from Indian Buddhist temples, the knowledge of which was transmitted with Buddhist teachings via Central Asia in the third and fourth centuries C.E. The most identifiable influence of Indian Buddhist architecture is the pagoda—the Chinese interpretation of the stupa. Like the stupa, the pagoda serves as a repository for important artifacts, most often scriptures and images, but occasionally relics. In Chinese Buddhism, the pagoda became a focal point of temple complexes and soon they were built on scales that greatly exceeded their Indian predecessors. During the Mongol Yuan dynasty, the temples that were built bore a resemblance to Tibetan Buddhist temples, due to the close links between Mongol leaders and the Tibetan Buddhist community.

Daoist Temples

In the earlier (and more philosophical) era of Daoism, there was little need for temples; the related ideals of non-materialism and of simplicity (Wu-wei) made the idea of temple construction counter-productive. However, the need for Daoist temples grew as a result of two related developments during the early and middle part of the first millennium: the introduction of Buddhism on a large scale, and the development of "religious" Daoism. This shift in the popular perception of Daoism suggested that this native Chinese religion was adapted to address the foreign tradition of Buddhism, within the context of the traditional community. As such, the emergence of Daoist temples (not coincidentally) coincides with the emergence of Buddhist temples in China. It is also not surprising that a great deal of Buddhist temple style is found in Daoist temples. Aside from differences in imagery, the two are quite similar in appearance.

Daoist temples can be found throughout China, but important complexes are located at the five sacred peaks, most notably Tai Shan.

Confucian Temples

Confucian temples are the most distinctive of the three temples types found in China. Though Confucius was not largely acknowledged in his own time, the first Confucian temple was built around 478 B.C.E. in his hometown (modern Qufu). It is likely that it began as a family shrine for a well-loved patriarch, though it eventually came to play a role in the Imperial Cult.

The general layout of Confucian temples is similar to those described above, but the emphasis on images is significantly less. The focus is on teachings rather than devotion. Evidence for this is found in the absence of major images (aside from the occasional statue of Confucius, a concession to the devotionally minded) and the abundance of lecture halls and, in larger complexes, stele with important works inscribed on them. Traditionally, the activities in a Confucian temple were related to classical learning, especially of music and ritual.

Japanese and Korean Temples

Just as Buddhist architectural styles were transmitted to China alongside Buddhist teaching, Korea and Japan inherited temple styles from China with the introduction of Buddhism to these regions. Like the Chinese, however, Korean and Japanese temple planners altered the basic design, either out of necessity or to suit local taste. Due to the ready availability of workable rock, Korean constructions were more frequently built of stone than their Chinese counterparts. Japanese temples, on the other hand, became less focused on prestige and grew more modest, including sections for rituals performed by monks in private. This was likely a result of the development of the highly iconoclastic Zen school.

Temples in the Americas

Mesoamerican Temples

Modern interpretations of the temples found throughout Mexico and Central America are based on archaeological remains and the records of early European explorers. As a result, understanding of these structures is still developing. The earliest Mesoamerican temples probably originated with the Olmecs and reached their pinnacle under the Mayans. Important sites can still be visited in modern Mexico and Guatemala, though they are no longer used for their original purposes.

The standard Mesoamerican style placed the temple atop a massive artificial pyramid. From the temple's main entrance, a staircase led to the summit of the pyramid, at which an open space was found, which was often the site of a large altar. The pyramids were built from either compressed earth or mud brick, and could contain the bodies and paraphernalia of deceased rulers. The evolution of the actual temples can be traced archaeologically, beginning with simple enclosures and progressing to complex masonry constructions. The temples contained ornate effigies of deities and were decorated with masks on the exterior. The scale of the pyramids was meant to convey a sense of grandeur, prestige, and power, often rising above the surrounding jungle and towering over nearby buildings.

The role of the temple in the Mesoamerican world was as a center for ritual religious practice and often sacrifices. The size of the sanctuary in the temple was too small for community gatherings, which has led archaeologists to theorize that it was used only by priests or religio-political leaders. As such, community worship was likely reduced to the base of the pyramid. Evidence suggests that temples were commissioned by rulers, and that successive advances in scale and complexity were to be testaments to their reigns.

Notes

- ↑ Leick, Gwendolyn, The Babylonians: An Introduction. (New York: Routledge, 2003), pp. 77-78, 109-128. ISBN 0415253152

- ↑ Mowinckel, Sigmund, The Psalms in Israel's Worship. Vol. 1. (Nashville, TN: Abingdon, 1962), pp. 109. ISBN 0687347351

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Levine, Baruch A. "Biblical Temple." The Encyclopedia of Religion. MacMillan. 1987. pg. 202-208. ISBN 0028971353

- Lip, Evelyn. "Chinese Temples and Deities." Times Books International. 1981. ISBN 9971650533

- Mehta, Rustam J. "Masterpieces of Indian Temples." D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co. 1974.

- Meister, Michael W., et al. "Temple." The Encyclopedia of Religion. MacMillan. 1987. pg. 368-389. ISBN 0028971353

- Gwendolyn Leick. The Babylonians: An Introduction. New York: Routledge. 2003. ISBN 0415253152

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.