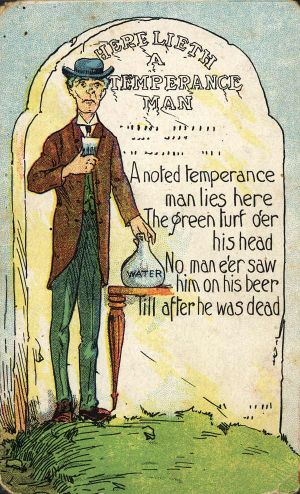

Temperance

The temperance movement attempted to greatly reduce the amount of alcohol consumed or even prohibit its production and consumption entirely. In predominantly Muslim countries, temperance is part of Islam. In predominantly Christian countries, forms of Christianity influenced by Wesleyan views on sanctification have strongly supported it at times. More specifically, religious or moralistic beliefs have often been the catalyst for temperance, though secular advocates do exist. The Women's Christian Temperance Union is a prominent example of a religion-based temperance movement. Supporters have sometimes called for a legal ban on the sale and consumption of alcohol but in the main the movement has called for self-restraint and self-discipline.

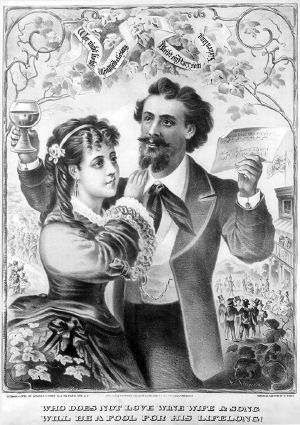

Most of the biggest supporters in all countries have been women, often as part of what some describe as feminism. The strong temperance movements of the early twentieth century found most of their support in women who were opposed to the domestic violence associated with alcohol abuse, and the large share of household income it could consume, which was especially burdensome to the low-income working class.

United States

In colonial America, informal social controls in the home and community helped maintain that the abuse of alcohol was unacceptable. As the colonies grew from a rural society into a more urban one, drinking patterns began to change. As the American Revolution approached, economic change and urbanization were accompanied by increasing poverty, unemployment, and crime. These emerging social problems were often blamed on drunkenness. Social control over alcohol abuse declined, anti-drunkenness ordinances were relaxed and alcohol problems increased dramatically.

It was in this environment that people began seeking an explanation and a solution for drinking problems. One suggestion had come from one of the foremost physicians of the period, Dr. Benjamin Rush. In 1784, Dr. Rush argued that the excessive use of alcohol was injurious to physical and psychological health (he believed in moderation rather than prohibition). Apparently influenced by Rush's widely discussed belief, about 200 farmers in a Connecticut community formed a temperance association in 1789. Similar associations were formed in Virginia in 1800 and New York State in 1808. Within the next decade, other temperance organizations were formed in eight states, some being statewide organizations.

The future looked bright for the young movement, which advocated temperance or moderation rather than abstinence. But many of the leaders overestimated their strength; they expanded their activities and took positions on profanation of the Sabbath, and other moral issues. They became involved in political in-fighting and by the early 1820s their movement stalled.

But some leaders persevered in pressing their cause forward. Americans such as Lyman Beecher, who was a Connecticut minister, had started to lecture his fellow citizens against all use of liquor in 1825 The American Temperance Society was formed in 1826 and benefited from a renewed interest in religion and morality. Within 10 years it claimed more than 8,000 local groups and over 1,500,000 members. By 1839, 15 temperance journals were being published. Simultaneously, many Protestant churches were beginning to promote temperance.

Prohibition

Between 1830 and 1840, most temperance organizations began to argue that the only way to prevent drunkenness was to eliminate the consumption of alcohol. The Temperance Society became the Abstinence Society. The Independent Order of Good Templars, the Sons of Temperance, the Templars of Honor and Temperance, the Anti-Saloon League, the National Prohibition Party and other groups were formed and grew rapidly. With the passage of time, "The temperance societies became more and more extreme in the measures they championed."

While it began by advocating the temperate or moderate use of alcohol, the movement now insisted that no one should be permitted to drink any alcohol in any quantity. It did so with religious fervor and increasing convictions.

The Maine law, passed in 1851 in Maine, was one of the first statutory implementations of the developing temperance movement in the United States. Temperance activist and mayor of Maine Neal Dow (also called the "Napoleon of Temperance" and the "Father of Prohibition" during his lifetime) helped force the law into existence. The passage of the law, which prohibited the sale of all alcoholic beverages except for "medicinal, mechanical or manufacturing purposes," quickly spread elsewhere, and by 1855 twelve states had joined Maine in total prohibition. These were "dry" states; states without prohibition laws were "wet."

The act was unpopular with many working class people and immigrants. Opposition to the law turned violent in Portland, Maine on June 2, 1855 during an incident known as the Maine law riot.

Temperance Education

In 1874, the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) was founded to decrease the impact of alcohol on families and society. Instrumental in helping forge the creation of the WCTU were Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, close friends and staunch supporters of the women's rights movement.[1] In 1880, the WCTU established a Department of Scientific Temperance Instruction in Schools and Colleges, with Mary Hunt as National Superintendent. She believed that voters "must first be convinced that alcohol and kindred narcotics are by nature outlaws, before they will outlaw them." Hunt pushed for the passage of laws promoting textbook instruction of abstinence and prohibition to all school children. Elizabeth D. Gelok was one of the women that taught Scientific Temperance Instruction at the Schools and Colleges for the students. She was also a member of the WCTU along with Mary Hunt. She was one of the most well-known and loved Scientific Temperance Instruction teachers because the students loved her strong faith in the WCTU. She really believed in the Women's Christian Temperance Union and wanted to do anything in her power to be heard. Elizabeth decided to use legislation to coerce the moral suasion of students, who would be the next generation of voters. This gave birth to the idea of the compulsory Scientific Temperance Instruction Movement.

By the turn of the century, Mary Hunt’s efforts along with Elizabeth Gelok's and the other teacher's proved to be highly successful. Virtually every state, the District of Columbia, and all United States possessions had strong legislation mandating that all students receive anti-alcohol education. Furthermore, the implementation of this legislation was closely monitored down to the classroom level by legions of determined and vigilant WCTU members throughout the nation.

Temperance writers viewed the WCTU's program of compulsory temperance education as a major factor leading to the establishment of National Prohibition with passage of the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Other knowledgeable observers, including the U.S. Commissioner of Education, agreed.

Because of the correlation between drinking and domestic violence—many drunken husbands abused family members—the temperance movement existed alongside various women's rights and other movements, including the Progressive movement, and often the same activists were involved in all of the above. Many notable voices of the time, ranging from first lady Lucy Webb Hayes, the wife of President Rutherford B. Hayes who was labeled "Lemonade Lucy" when she refused to serve alcohol in the White House, to Susan B. Anthony, a pioneer in the temperance movement who helped to organize the first women's temperance society after being refused admittance to a similar organization because she was a woman, were active in the movement. Anthony would advocate divorce as a resolution for marriage to a habitually drunken, and thus inept, man. Carrie Nation was a staunch believer in the corrupting influence of alcohol over fathers and husbands who consequently destroyed thier families after succumbing to drunkenness. She had lived in such a home with her first husband, Charles Gloyd, bringing about their divorce. Nation wielded a signature hatchet, which she used to destroy alcoholic stores in various businesses. She drew much attention for her efforts and was highly dedicated to the cause of prohibition. In Canada, Nellie McClung was a longstanding advocate of temperance. As with most social movements, there was a gamut of activists running from violent (Carrie Nation) to mild (Neal S. Dow).

Many former abolitionists joined the temperance movement and it was also strongly supported by the second that began to emerge after 1915.

For decades prohibition was seen by temperance movement zealots and their followers as the almost magical solution to the nation's poverty, crime, violence, and other ills. On the eve of prohibition the invitation to a church celebration in New York said "Let the church bells ring and let there be great rejoicing, for an enemy has been overthrown and victory crowns the forces of righteousness." Jubilant with victory, some in the WCTU announced that, having brought Prohibition to the United States, it would now go forth to bring the blessing of enforced abstinence to the rest of the world.

The famous evangelist Billy Sunday staged a mock funeral for John Barleycorn and then preached on the benefits of prohibition. "The reign of tears is over," he asserted. "The slums will soon be only a memory. We will turn our prisons into factories and our jails into storehouses and corncribs." Since alcohol was to be banned and since it was seen as the cause of most, if not all, crime, some communities sold their jails. One sold its jail to a farmer who converted it into a combination pig and chicken house while another converted its jail into a tool house.

Anti-Saloon League

The Anti-Saloon League, under the leadership of Wayne Wheeler stressed political results and utilized pressure politics. It did not demand that politicians change their drinking habits, only their votes in the legislature. Other organizations like the Prohibition Party and the WCTU lost influence to the League. The League mobilized its religious coalition to pass state (and local) legislation. Energized by the anti-German sentiment during World War I, in 1918 it achieved the main goal of passage of the 18th Amendment establishing National Prohibition.

Temperance organizations

Temperance organizations of the United States played an essential role in bringing about ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution establishing national prohibition of alcohol. They included:

- the American Issue Publishing House

- the American Temperance Society

- the Anti-Saloon League of America

- the British Women's Temperance Association

- the Catholic Total Abstinence Union of America

- the Committee of Fifty (1893)

- the Daughters of Temperance

- the Department of Scientific Temperance Instruction

- the Independent Order of Good Templars

- the Knights of Father Matthew

- the Lincoln-Lee Legion

- the Methodist Board of Temperance, Prohibition, and Public Morals

- the National Temperance Society and Publishing House

- the People's Democratic Temperance League

- the People's Temperance League

- the Prohibition Party

- the Scientific Temperance Federation

- the Sons of Temperance

- the Templars of Honor and Temperance

- the Abstinence Society

- the Women’s Christian Temperance Union

- the National Temperance Council

- the World League Against Alcoholism (a pro-prohibition organization)

There was often considerable overlap in membership in these organizations, as well as in leadership. Prominent temperance leaders in the United States included Bishop James Cannon, Jr., James Black, Ernest Cherrington, Neal S. Dow, Mary Hunt, William E. Johnson (known as "foot" Johnson), Carrie Nation, Howard Hyde Russell, John St. John, Billy Sunday, Father Mathew, Andrew Volstead, and Wayne Wheeler.

Temperance and the Woman's Movement

Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony perhaps more widely known for their work on behalf of women's suffrage were also instrumental in founding the Woman's State Temperance Society (1852-1853). Another champion of women's rights, Frances Willard was also a strong supporter of the temperance movement. She held the office of president of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union for almost 20 years from 1874 when she was named president of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (helping launch the group on an international scale during her tenure) until 1892 when she founded the magazine The Union Signal. Her influence was influential in helping ensure the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment, as she was dedicated to lecturing on and promoting temperance. Similarly, Frances Harper championed abolition of slavery, rights for freed women of color and temperance. In 1873, Harper became Superintendent of the Colored Section of the Philadelphia and Pennsylvania Women's Christian Temperance Union. In 1894, she helped found the National Association of Colored Women and served as its vice president from 1895 through 1911. She believed in solving social problems from the local level and was an activist in the affairs of her own black community in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

United Kingdom

Starting from a group of workers "taking the pledge," the British Association for the Promotion of Temperance was established by 1835.[2] Within a few years the Temperance movement was advocating complete teetotalism rather than moderation.

In 1853, inspired by the Maine law in the United States, the United Kingdom Alliance was formed aimed at promoting a similar law prohibiting the sale of alcohol in the UK.

In Wales Lady Llanover closed all the public houses on her estate and was an outspoken critic of the evils of drink.

Quakers and the Salvation Army lobbied parliament to restrict alcohol sales.

Nonconformists were active with large numbers of Baptist and Congregational ministers being teetotal.

The British Women's Temperance Association persuaded men to stop drinking and the Band of Hope founded in Leeds in 1847, and active today, was an organization for working class children.

The National Temperance Federation formed in 1884 was associated with the Liberal Party.[3]

Ireland

In Ireland, a Catholic priest Theobald Matthew persuaded thousands to sign the pledge.

New Zealand

In New Zealand, at the end of the nineteenth century it became apparent that problems associated with settlement, such as larrikinism and drunkenness, were growing in society. Increasing urbanization heightened public awareness of the gap between social aspirations and reality of the young colony. Generalizations from newspapers, visiting speakers and politicians in the late 1890s allowed development of large public overreaction and fervor to the magnitude of the problem of alcohol. It became the firm opinion of a number of prominent New Zealanders that the colony’s problems were associated with alcohol.

Despite the efforts of the temperance movement the rate of convictions for drunkenness remained constant in New Zealand. The rapid increase in the number of convictions for public drunkenness was more a reflection of the growing population rather than social denigration.

The pressure applied from the temperance movement crippled New Zealand’s young wine industry post World War I.

In 1834, the first recorded temperance meeting was held in the Bay of Islands (Northland). The 1860s saw the foundation of a large number of temperance societies. Many provinces passed licensing ordinances giving residents the right to secure, by petition, the cancellation or granting of liquor licenses in their district. The Licensing Act of 1873 allowed the prohibition of liquor sales in districts if petitioned by two-thirds of residents. In this year a national body called the ‘New Zealand Alliance for Suppression and Abolition of Liquor Traffic’ was formed pushing for control of the liquor trade as a democratic right. In 1893, the Alcoholic Liquors Sale Control Act aligned licensing districts with parliamentary electorates. In 1894, Clutha electorate voted ‘no-licence’. In 1902, Mataura and Ashburton voted ‘no-licence’. In 1905, Invercargill, Oamaru and Greylynn voted ‘no-licence’. In 1908, Bruce, Wellington suburbs, Wellington South, Masterton, Ohinemuri and Eden voted ‘no-licence’ and many winemakers were denied the right to sell their wines locally and were forced out of business. In 1911, the Liquor Amendment Act provided for national poll on prohibition and the New Zealand Viticultural Association was formed to “save this fast decaying industry by initiation of such legislation as will restore confidence among those who after long years of waiting have almost lost confidence in the justice of the Government. Through harsh laws and withdrawal of government support and encouragement that had been promised, a great industry had been practically ruined.” In 1914, sensing a growing feeling of wowserism, Prime Minister Massey lambasted Dalmatian wine as ‘a degrading, demoralizing and sometimes maddening drink’ (Dalmatians featured prominently in the New Zealand wine industry at this time). On April 10, 1919, a national poll for continuance was carried with 51 percent, due only to votes of Expeditionary Force soldiers returning from Europe. On December 7, a second poll failed by 3,363 votes to secure prohibition over continuance or state purchase and control of liquor. Restrictive legislation was introduced on sale of liquor. In 1928, the percentage of prohibition votes begin to decline.

Australia

A variety of organizations promoted temperance in Australia. While often connected with Christian groups, including the Roman Catholic and the Anglican churches and Methodist groups, there were also groups with international links such as the Independent Order of Rechabites, the Band of Hope and the Woman's Christian Temperance Union.

Notes

- ↑ Stanton would later distance herself from the WCTU and her Christian peers in favor of throwing her sole support behind the crusade for women's rights.

- ↑ Brian Harrison, Drink & the Victorians, The Temperance Question in England 1815-1872, London: Faber and Faber, 1971.

- ↑ Temperance Society, Spartacus Educational. Retrieved December 13, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Blocker, Jack S., David M. Fahey, and Ian R. Tyrrell (eds.). Alcohol and Temperance in Modern History: An International Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio, 2003. ISBN 1576078337

- Bordin, Ruth Birgitta Anderson. Woman and Temperance: The Quest for Power and Liberty, 1873-1900. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1981 ISBN 9780877221579

- Cherrington, Ernest. The Evolution of Prohibition in the United States of America. Westerville, OH: American Issue Publishing Co., 1920.

- Cherrington, Ernest (ed.). Standard Encyclopaedia of the Alcohol Problem. 6 volumes This source contains comprehensive international coverage to late 1920s. Westerville, OH: American Issue Publishing Co., 1925-1930.

- Clark, Norman H. Deliver Us From Evil: An Interpretation of American Prohibition. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1976 ISBN 9780393055849

- Dannenbaum, Jed. "The Origins of Temperance Activism and Militancy among American Women." Journal of Social History 14 (1981): 235-36.

- Heath, Dwight B. (ed.). International Handbook on Alcohol and Culture. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1995 ISBN International Handbook on Alcohol and Culture'

- Harrison, Brian. Drink & the Victorians, the Temperance question in England 1815-1872. London: Faber and Faber, 1971. ISBN 9781853310461

- Jensen, Richard. The Winning of the Midwest, Social and Political Conflict, 1888-1896. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1971. ISBN 9780226398259

- McConnell, D. W. "Temperance Movements." In Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. edited by Edwin R. A. Seligman and Alvin Johnson. New York: Macmillan, 1933.

- Odegard, Peter H. Pressure Politics: The Story of the Anti-Saloon League. New York: Columbia University Press, 1928.

- Seabury, Olive. The Carlisle State Management Scheme: A 60 year experiment in Regulation of the Liquor Trade. Carlisle: Bookcase, 2007.

- Sheehan, Nancy M. "The WCTU and education: Canadian-American illustrations." Journal of the Midwest History of Education Society. 115-133. 1981.

- Spartacus Educational. Temperance Society Retrieved December 13, 2007.

- Timberlake, James H. Prohibition and the Progressive Movement, 1900-1920. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1963.

- Tracy, Sarah W., and Caroline Jean Acker. Altering American Consciousness: The History of Alcohol and Drug Use in the United States, 1800-2000. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2004. ISBN 1558494251

- Tyrrell, Ian. Woman's World/Woman's Empire: The Woman's Christian Temperance Union in International Perspective, 1880-1930. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

External links

All links retrieved February 26, 2023.

- Temperance Movement – (entry in the New Georgia Encyclopedia)

- Temperance Hymn Book And Minstrels – 105 Songs Hymn & Odes from the American Temperance Union (complete 1841 book)

- Temperance Town, a suburb in Cardiff, Wales, where alcohol was banned

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.