Sabbath

Sabbath or Shabbat (Hebrew: שבת, shabbāt, "rest"; Shabbos or Shabbes in Ashkenazic pronunciation), is the weekly day of rest in Judaism, some forms of Christianity, and other religious traditions. In Judaism, it is observed from before sundown on Friday until after nightfall on Saturday. It is considered a holy day, and, in Orthodox traditions, is accompanied by special prayers in both home and synagogue, as well as by a strict prohibition of nearly all forms of work.

Christianity inherited the Jewish tradition of Sabbath, but gradually replaced Saturday with Sunday as a day of special worship and evolved a less strict attitude toward the prohibition of work on this day. After the Protestant Reformation, some Christian denominations returned to the observance of a Saturday Sabbath.

For Muslims, Friday is a type of Sabbath in which normal noon-time prayers are said communally in mosques, although worshipers are allowed to return to work afterward. Buddhism practices a tradition similar to Sabbath, known as Uposatha. Secular laws requiring stores to close on Sundays or limiting the work week to five or six days also have their roots in the Sabbath tradition.

Jewish tradition holds that the Sabbath was instituted by God to commemorate his own resting on the seventh day of creation after creating Adam and Eve.

Sabbath in Judaism

Etymology and origins

Shabbat is the source for the English term Sabbath and for similar words in many languages, such as the Arabic As-Sabt (السبت), the Armenian Shabat (Շաբաթ), the Persian shambe, Spanish and Portuguese Sábado, the Greek Savato, the Russian "subbota" (суббота) and the Italian word Sabato—all referring to Saturday. The Hebrew word Shabbat comes from the Hebrew verb shavat, which literally means "to cease." Thus, Shabbat is the day of ceasing from work. It is likewise understood that God "ended" (kalah) his labor on the seventh day of creation after making the universe, all living things, and humankind (Genesis 2:2-3, Exodus 20:11.

The first biblical mention of the Sabbath as such comes in Exodus 16, where the Israelites are commanded not to gather manna on the seventh day (Exodus 16). After this, the Sabbath was said to be formally instituted in the Ten Commandments: "Remember the Sabbath day by keeping it holy." In Exodus 31:12, the Sabbath is called a "sign" between God and Israel, as well as a covenant. The Sabbath command reappears several times in the laws of Exodus, Leviticus and Numbers. In Deuteronomy chapter 5, the Sabbath commandment is reiterated but instead of commemorating creation it symbolizes the redemption of Israel from Egypt.

The observance of the Sabbath is considered so important that the punishment given in ancient times for desecrating Shabbat was stoning to death, the most severe punishment within Jewish law, although in later times this was not enforced. The prophets sometimes criticized the hypocritical tradition of Sabbath observance without a commitment to justice, declaring, for example:

- Your incense is detestable to me.

- New Moons, Sabbaths and convocations—

- I cannot bear your evil assemblies. (Isaiah 1:13)

During the Maccabean revolt of the second century B.C.E., some Jews were so strict in their observance of the Sabbath that they allowed themselves to be killed by their enemies rather than fight. By the turn of the Common Era, rabbinical debates concerning the proper observance of the Sabbath resulted in a diversity of opinions about what was permissible on this day.

The historical origin of the Sabbath tradition is much debated. Beside the supposed original Sabbath observed by God on the seventh day of creation, Shabbat is mentioned a number of times elsewhere in the Torah, most notably as the fourth of the Ten Commandments (Exodus 20:8-11 and Deuteronomy 5:12-15). Traditionally these laws were instituted by Moses at God's command. However, critical scholars believe that the Sabbath tradition actually emerged later in Israelite history, not during their nomadic wilderness existence, but after a settled agricultural and town culture had been established.

Observance

Jewish law defines a day as ending at dusk, with the next day then beginning at nightfall. Thus, the Jewish Sabbath begins just before sundown Friday night and ends at after nightfall Saturday night.

Jewish tradition describes the Sabbath as having three purposes:

- A commemoration of the Israelites' redemption from slavery in Ancient Egypt;

- A commemoration of God's creation of the universe; on the seventh day God rested from (or ceased) his work;

- A foreshadowing of the world in Messianic times.

Judaism accords Shabbat the status of a joyous holy day. It is the first holy day mentioned in the Bible, and God is thought to be the first one to observe it (Genesis 2:1-3). Jewish liturgy treats the Sabbath as a "bride" and "queen," to be welcomed with joy by the congregation. On Shabbat the reading of the Torah is divided into seven sections, more than on any other holy day. Following this is a reading from the Hebrew prophets. A Talmudic tradition holds that the Messiah will come if every Jew properly observes two consecutive Sabbaths (Shabbat 118).

Shabbat is a day of celebration as well as one of prayer. In most Jewish communities, three sumptuous meals are eaten each Shabbat after synagogue services conclude: one on Friday night, another Saturday around noon, and a third late Saturday afternoon before the conclusion of the Shabbat. However all cooking of these meals must be done prior to the start of the Sabbath. Many more Jews attend services at a synagogue during Shabbat than on weekdays. With the exception of Yom Kippur, days of public fasting are postponed or advanced if they coincide with Shabbat, and mourners are forbidden to express public signs of grief.

According to Rabbinic literature, Jews are commanded by God to both observe (by refraining from forbidden activity) and remember (with words, thoughts, and actions) the Sabbath. These two actions are symbolized by lighting candles late Friday afternoon by Jewish women, usually the mother, although men who live alone are required to do so themselves. At least one candle is required, and two are customary.

Orthodox Shabbat laws include:

- Recitation of kiddush (a prayer of sanctification) over a cup of wine before the first Sabbath meal and after the conclusion of morning prayers.

- Eating three sumptuous meals initiated with two loaves of bread, usually braided challah.

- Recitation of Havdalah, ("separation") at the conclusion on Saturday night over a cup of wine, and with the use of fragrant spices and a candle.

- Enjoying Shabbat (Oneg Shabbat), include activities such as eating tasty food, resting, study, singing, or engaging in sexual relations with one's spouse.

- Honoring Shabbat (Kavod Shabbat) i.e. making an effort during the week to prepare for each upcoming Sabbath, such as taking a shower on Friday, getting a haircut, beautifying the home and wearing special clothes.

Prohibited activities

Jewish law prohibits doing any form of "work" or traveling long distances on Shabbat. Various Jewish denominations view the prohibition on work in different ways. Observant Orthodox and many Conservative Jews do not perform the 39 categories of activity prohibited by Mishnah Tractate Shabbat 7:2 in the Talmud.

In the event that a human life is in danger, a Jew is not only allowed, but required, to violate any Sabbath law that stands in the way of saving that person. However in ancient times this exception was not followed by all sects. For example the Essene text known as the Damascus Document specifically prohibits the lowering of a ladder into a cistern to help a drowning person on the Sabbath.

Debates over the interpretation of Sabbath laws have been in evidence since ancient times. More recently arguments have arisen over such matters as riding in elevators or turning on light switches (thought to be a form of kindling a fire, which is prohibited). A common solution involves pre-set timers for electric appliances to turn them on and off automatically, with no human intervention on Shabbat itself.

When there is an urgent human need which is not life-threatening, it is possible to perform seemingly "forbidden" acts by modifying the relevant technology to such an extent that no law is actually violated. An example is the "Sabbath elevator." In this mode, an elevator will stop automatically at every floor, allowing people to step on and off without anyone having to press any buttons that activate electrical switches. However, many rabbinical authorities consider the use of such elevators by people who could use the stairs to be as a violation of the Sabbath.

Adherents of Reform Judaism and Reconstructionist Judaism, generally speaking, believe that it is up to the individual Jew to determine whether to follow those prohibitions on Shabbat or not. Some Jews in these traditions, as well as "secular Jews," do not observe Sabbat strictly, or even not at all. Others argue that such activities as cooking, sports, or driving across town to see relatives are not only enjoyable, but are pious activities that enhance Shabbat and its holiness. Many Reform Jews also believe that what constitutes "work" is different for each person; thus only what the person considers "work" is forbidden.

Christian sabbaths

In most forms of Christianity, the Sabbath is a weekly religious day of rest as ordained by one of the Ten Commandments: the third commandment by Roman Catholic and Lutheran numbering, and the fourth by Eastern Orthodox and most Protestant numbering. In Christian-based cultures today, the term "sabbath" can mean one of several things:

- Saturday as above, in reference to the Jewish day of rest

- Sunday, as a synonym for "the Lord's Day" in commemoration of the resurrection of Christ, for most Christian groups

- Any day of rest, prayer, worship, or ritual, as in "Friday is the Muslim Sabbath"

Early developments

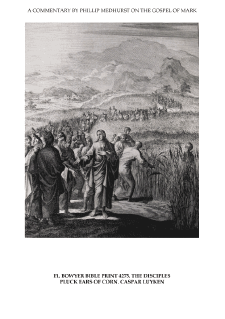

In the New Testament, the Sabbath was a point of controversy in the ministry of Jesus. Although an observant Jew who stressed the importance of fulfilling the Law Matthew 5:17-20, Jesus took a relatively liberal attitude toward what was permissible on the Sabbath. Like other rabbis of his day, he also taught that it was right to do good—specifically referring to healing—on the Sabbath (Mark 3:4, Luke 6:9). However, when accused of breaking the Sabbath by allowing his disciples to pick and eat grain as they walked through a field, he justified this act by declaring that "the Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath" (Mark 2:27). This led to a later Christian tradition of interpreting the Sabbath work restrictions fairly loosely.

In the early church, the Sabbath continued to be a time of communal gathering for Jewish Christians at the synagogue (Acts 15:21). Christians, both Jews and Gentiles, observed the seventh day as the Sabbath for some time into the Christian Era. At the same time, worship on the first day of the week, or Sunday, appeared quite early. The Book of Revelation (mid-late first century) speaks of Sunday as the “Lord’s Day” (Rev. 1:10), apparently in commemoration of Jesus' resurrection on that day.

When the Jerusalem church was scattered and the Gentile churches came to the fore after 70 C.E., Jewish-style Sabbath-keeping began to wane. Justin Martyr (mid-second century), describes the Lord’s Day as a day of gathering and worship. In Rome, Carthage, Alexandria, and other churches, the observance of the Saturday Sabbath gradually ceased. Eventually, keeping the Jewish Sabbath was condemned as a Judaizing practice.

By the early fourth century, Sunday worship was the norm in many areas of the Roman Empire. In 321, Emperor Constantine I decreed Sunday to be a general day of rest and worship in order to encourage church attendance, although farm labor was exempted. The Council of Laodicea, around 365 C.E., attempted to put a stop to the practice of Saturday Sabbath observance for Christians. It decreed that Christians must not rest on the Jewish Sabbath but should work on that day and rest on the Lord's Day.

However, the observance of Saturday Sabbaths remained part of Christian tradition in some areas. In the late fourth century, Bishop John Chrysostom felt compelled to preach vehemently against the Christians of Antioch observing Shabbat and other Jewish customs. In the fifth century, the church historian Socrates Scholasticus indicated that seventh-day Sabbath observance was still the norm in the Eastern Roman Empire: "Although almost all churches throughout the world celebrate the sacred mysteries on the Sabbath of every week, yet the Christians of Alexandria and at Rome, on account of some ancient tradition, have ceased to do this." (Church History, 5) Sozomen's Church History likewise states: "Assemblies are not held in all churches at the same time or in the same manner. The people of Constantinople, and almost everywhere, assemble together on the Sabbath, as well as on the first day of the week, which custom is never observed at Rome or at Alexandria." By the Middle Ages, however, Sunday had become the nearly universal Christian Sabbath, and would remain so until after the Protestant Reformation.

Besides being celebrated on Sunday, Christian Sabbaths differed from their Jewish counterparts in other ways. For example, while work was generally discouraged, it was defined more in terms of professional labor rather than such activities as cooking, traveling, housework, and service industries such as inns. There were also no prohibitions regarding the use of animals and wagons or coaches to arrive in church. While Sunday dinners might be special ones in homes which could afford this, no special Sabbath rituals were associated with the home, as in Judaism.

Protestant Sunday-observance

The Christian attitude toward the Sabbath began to diversify considerably after the Protest Reformation. In some areas, a new rigorism was brought into the observance of the Lord's Day, especially among the Puritans of England and Scotland, in reaction to the relative laxity with which Sunday observance was customarily kept. One expression of this influence survives in the Westminster Confession of Faith, Chapter 21, Of Religious Worship, and the Sabbath Day, Section 7-8:

(God) hath particularly appointed one day in seven, for a Sabbath, to be kept holy unto him: which, from the beginning of the world to the resurrection of Christ, was the last day of the week; and, from the resurrection of Christ, was changed into the first day of the week, which, in Scripture, is called the Lord’s day, and is to be continued to the end of the world, as the Christian Sabbath. This Sabbath is then kept holy unto the Lord, when men, after a due preparing of their hearts, and ordering of their common affairs beforehand, do not only observe a holy rest, all the day, from their own works, words, and thoughts about their worldly employments and recreations, but also are taken up, the whole time, in the public and private exercises of his worship, and in the duties of necessity and mercy.

Another trend within Protestant Christianity is to consider Sabbath observance as such, either on Saturday or Sunday, is an obsolete custom, since the Law of Moses was fulfilled by Christ. This view, based on a interpretation of the teachings of the Apostle Paul regarding the Jewish law, holds that only God's moral law is binding on Christians, not the Ten Commandments as such. In this interpretation, Sunday is observed as the day of Christian assembly and worship in accordance with church tradition, but the sabbath commandment is dissociated from this practice.

Christian sabbatarianism

Seventh-day Sabbath worship did not initially become prevalent among European Protestants, and seventh-day sabbatarian leaders and churches were persecuted as heretics in England. The Seventh Day Baptists, however, exercised an important influence on other sects, especially in the middle of the nineteenth century in the United States, when their doctrines were instrumental in founding the Seventh-day Adventist Church and the Seventh-day Church of God. Seventh-day Adventists have traditionally taught that observing the Sabbath on the seventh-day Sabbath constitutes a providential test, leading to the sealing of God's people during the end times.

The Worldwide Church of God, which was founded after a schism in the Seventh-day Church of God in 1934, was founded as a seventh-day Sabbath-keeping church. However, in 1995 it renounced sabbatarianism and moved toward the Evangelical "mainstream." This move caused additional schisms, with several groups splitting off to continue to observe the Sabbath as new church organizations.

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, consisting of an estimated 40 million believers, is the largest Christian denomination to observe a Saturday Sabbath, although it also commemorates the Lord's Day on Sunday. The primarily Chinese True Jesus Church also supports a Saturday Sabbath. Some, though not all, Messianic Jews—meaning Jews who accept Jesus—also observe Sabbath in the traditional Jewish manner.

Sabbaths in other traditions

- The Muslim Sabbath is kept on Friday, which is the day for communal prayer. However, the only special feature of this day for Muslims is that they are encouraged to perform the normal noon prayer communally. After congregating at a mosque for prayer, Muslims are free to return to work as normal. Some historians believe that Muslims initially kept the Sabbath in a manner which closely resembled the Jewish tradition for at least the first two centuries after Muhammad. Traditionally, however, Muslims believe that Friday, as the sixth day of the week, was chosen by the Prophet Muhammad himself, in commemoration of the creation of human beings on the “sixth day,” as well as to differentiate Islam from both Christians and Jews.

- Theravada Buddhism also has a tradition similar to Sabbath, known as Uposatha, believed to have been in existence from the Buddha's time (500 B.C.E.). The Buddha taught that the Uposatha day is for "the cleansing of the defiled mind," resulting in inner calm and joy. Uposatha is observed about once a week in accordance with the four phases of the moon. In some communities, only the new moon and full moon are observed as Uposatha days. On these days, disciples, monks, and nuns intensify their religious practice, deepen their knowledge through study and meditation, and express communal commitment through almsgiving and hospitality.

- In the Middle Ages, a Witches' Sabbath was a supposed meeting of those who practice witchcraft, often thought to be held at midnight during certain phases of the moon and involving obscene or blasphemous rituals. European written records tell of innumerable cases of persons accused of taking part in these gatherings from the Middle Ages to the seventeenth century or later. However, much of what was written about them may be the product of popular imagination and confessions under torture.

- In neo-paganism and Wicca, the Wheel of the Year is a term for the annual cycle of the Earth's seasons, consisting of eight festivals, referred to by Wiccans as "Sabbats."

- In secular society, the 40-hour or 36-hour work week evolved out of the Sabbath tradition, extending the legally-mandated rest period from one day in seven to two or more. Such days of rest are no longer directly associated with the principle of a Jewish or Christian Sabbath. However, vestiges of religious Sabbaths in secular societies can be seen in such phenomena as "blue laws" in some jurisdictions, mandating stores to close on Sunday or banning the sale of alcohol.

- A "sabbatical" is a longer period of rest from work, a hiatus, typically two months or more. The concept relates to biblical commandments (Leviticus 25, for example) requiring that fields be allowed to lie fallow in the seventh year. In the modern sense, one goes on sabbatical to take a break from work or fulfill a goal such as writing a book or traveling extensively for research. Some universities and other institutional employers of scientists, physicians, and/or academics offer a paid sabbatical as an employee benefit, called sabbatical leave. Some companies offer an unpaid sabbatical for people wanting to take career breaks.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allender, Dan B. Sabbath. Nashville, Tenn: Thomas Nelson, 2008. ISBN 9780849901072

- Heschel, Abraham Joshua. The Sabbath: Its Meaning for Modern Man. New York: Farrar, Straus and Young, 1951. ISBN 9780374512675

- Lowery, R. H. Sabbath and Jubilee (Understanding biblical themes). St. Louis, Mo: Chalice Press, 2000. ISBN 9780827238268

- Ray, Bruce A. Celebrating the Sabbath: Finding Rest in a Restless World. Phillipsburg, NJ: P & R Pub, 2000. ISBN 9780875523941

- Ringwald, Christopher D. A Day Apart: How Jews, Christians, and Muslims Find Faith, Freedom, and Joy on the Sabbath. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 9780195165364

External links

All links retrieved December 22, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.