Christianity

| Part of a series of articles on Christianity | ||||||

| ||||||

|

Foundations Bible Christian theology History and traditions

Topics in Christianity Important figures | ||||||

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus. Christians believe that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, whose coming as the Messiah was prophesied in the Hebrew Bible (called the Old Testament in Christianity) and chronicled in the New Testament.

The creeds of various Christian denominations generally hold in common Jesus as the Son of God—the Logos incarnated—who ministered, suffered, and died on a cross, but rose from the dead for the salvation of humankind; and referred to as the gospel, meaning the "good news." The four canonical gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John describe Jesus' life and teachings, with the Old Testament as the gospels' respected background. Christianity remains culturally diverse in its Western and Eastern branches, and doctrinally diverse concerning justification and the nature of salvation, ecclesiology, ordination, and Christology.

Despite being the world's largest and most widespread religion, Christians remain greatly persecuted in many regions of the world, particularly in the Middle East, North Africa, East Asia, and South Asia. Christians have not only been the victims of persecution, but have also been the perpetrators, even to the level of violence, despite the strong doctrinal and historical imperative against violence contained in Jesus' teachings which promote nonviolence and "love of enemies."

Etymology

Early Jewish Christians referred to themselves as "The Way" (Template:Lang-grc-x-koine), probably coming from Isaiah 40:3 KJV, "prepare the way of the Lord." It appears in the Acts of the Apostles, Acts 9:2 KJV, Acts 19:9 KJV, and Acts 19:23 KJV. Some English translations of the New Testament capitalize "the Way" (such as the New King James Version and the English Standard Version), indicating that this was how "the new religion seemed then to be designated,"[1] whereas others treat the phrase as indicative, for example The Syriac version reads, "the way of God" and the Vulgate Latin version, "the way of the Lord."[2]

According to Acts 11:26 KJV, the term "Christian" (Χρῑστῐᾱνός, Khrīstiānismós), meaning "followers of Christ" in reference to Jesus's disciples, was first used in the city of Antioch by the non-Jewish inhabitants there. Ignatius of Antioch used the term "Christianity/Christianism" around 100 C.E.[3]

Beliefs

While Christians worldwide share basic convictions, there are differences of interpretations and opinions of the Bible and sacred traditions on which Christianity is based.[4]

Creeds

Concise doctrinal statements or confessions of religious beliefs are known as creeds. They began as baptismal formulae and were later expanded during the Christological controversies of the fourth and fifth centuries to become statements of faith. "Jesus is Lord" is the earliest creed of Christianity and continues to be used, as with the World Council of Churches.[5]

The Apostles' Creed is the most widely accepted statement of the articles of Christian faith. It is used by a number of Christian denominations for both liturgical and catechetical purposes, most visibly by liturgical churches of Western Christian tradition, including the Latin Church of the Catholic Church, Lutheranism, Anglicanism, and Western Rite Orthodoxy. It is also used by Presbyterians, Methodists, and Congregationalists.

This particular creed was developed between the second and ninth centuries. Its central doctrines are those of the Trinity and God the Creator. Each of the doctrines found in this creed can be traced to statements current in the apostolic period. The creed was apparently used as a summary of Christian doctrine for baptismal candidates in the churches of Rome.[6] Its points include:

- Belief in God the Father, Jesus Christ as the Son of God, and the [Holy Spirit]]

- The death, descent into hell, resurrection and ascension of Christ

- The holiness of the Church and the communion of saints

- Christ's second coming, the Day of Judgement and salvation of the faithful

The Nicene Creed was formulated, largely in response to Arianism, at the Councils of Nicaea and Constantinople in 325 and 381 respectively, and ratified as the universal creed of Christendom by the First Council of Ephesus in 431.[7]

The Chalcedonian Definition, or Creed of Chalcedon, developed at the Council of Chalcedon in 451, though rejected by the Oriental Orthodox, taught Christ "to be acknowledged in two natures, inconfusedly, unchangeably, indivisibly, inseparably": one divine and one human, and that both natures, while perfect in themselves, are nevertheless also perfectly united into one person.[8]

The Athanasian Creed, received in the Western Church as having the same status as the Nicene and Chalcedonian, says: "We worship one God in Trinity, and Trinity in Unity; neither confounding the Persons nor dividing the Substance".[9]

Most Christians (Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Protestant alike) accept the use of creeds and subscribe to at least one of the creeds mentioned above.

Certain Evangelical Protestants, though not all of them, reject creeds as definitive statements of faith, even while agreeing with some or all of the substance of the creeds. Also rejecting creeds are groups with roots in the Restoration Movement, such as the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), the Evangelical Christian Church in Canada, and the Churches of Christ.[10]

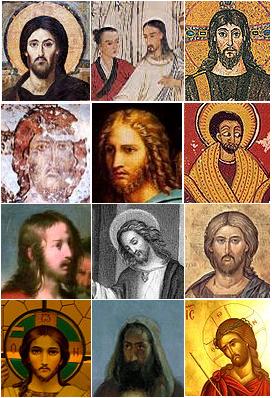

Jesus

The central tenet of Christianity is the belief in Jesus as the Son of God and the Messiah (Christ).[11] Christians believe that Jesus, as the Messiah, was anointed by God as savior of humanity and hold that Jesus's coming was the fulfillment of messianic prophecies of the Old Testament. The Christian concept of messiah differs significantly from the contemporary Jewish concept. The core Christian belief is that through belief in and acceptance of the death and resurrection of Jesus, sinful humans can be reconciled to God, and thereby are offered salvation and the promise of eternal life.[12]

While there have been many theological disputes over the nature of Jesus over the earliest centuries of Christian history, generally, Christians believe that Jesus is God incarnate and "true God and true man" (or both fully divine and fully human). Jesus, having become fully human, suffered the pains and temptations of a mortal man, but did not sin. As fully God, he rose to life again. According to the New Testament, he rose from the dead,[13] ascended to heaven, is seated at the right hand of the Father, and will ultimately return[14] to fulfill the rest of the Messianic prophecy, including the resurrection of the dead, the Last Judgment, and the final establishment of the Kingdom of God.

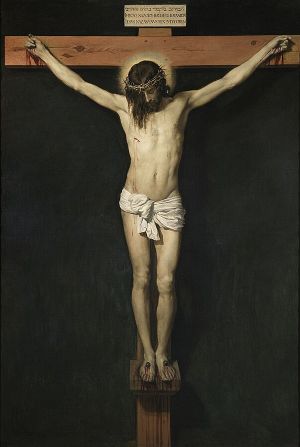

Among Christian beliefs, the death and resurrection of Jesus are two core events on which much of Christian doctrine and theology is based. According to the New Testament, Jesus was crucified, died a physical death, was buried within a tomb, and rose from the dead three days later.[15] Christians consider the resurrection of Jesus to be the cornerstone of their faith and the most important event in history.[16]

The death and resurrection of Jesus are usually considered the most important events in Christian theology, partly because they demonstrate that Jesus has power over life and death and therefore has the authority and power to give people eternal life.[17] Jesus' death and resurrection are commemorated by Christians in all worship services, with special emphasis during Holy Week, which includes Good Friday and Easter Sunday.

Salvation

Paul the Apostle, like Jews and Roman pagans of his time, believed that sacrifice can bring about new kinship ties, purity, and eternal life. For Paul, the necessary sacrifice was the death of Jesus: Gentiles who are "Christ's" are, like Israel, descendants of Abraham and "heirs according to the promise"[18][19] The God who raised Jesus from the dead would also give new life to the "mortal bodies" of Gentile Christians, who had become with Israel, the "children of God," and were therefore no longer "in the flesh."[20]

Modern Christian churches tend to be much more concerned with how humanity can be saved from a universal condition of sin and death than the question of how both Jews and Gentiles can be in God's family. According to Eastern Orthodox theology, based upon their understanding of the atonement as put forward by Irenaeus' recapitulation theory, Jesus' death is a ransom. This restores the relation with God, who is loving and reaches out to humanity, and offers the possibility of becoming the kind of humans God wants humanity to be.

According to Catholic doctrine, Jesus' death satisfies the wrath of God, aroused by the offense to God's honor caused by human's sinfulness. The Catholic Church teaches that salvation does not occur without faithfulness on the part of Christians; converts must live in accordance with principles of love and ordinarily must be baptized.[21]

In Protestant theology, Jesus' death is regarded as a substitutionary penalty carried by Jesus, for the debt that has to be paid by humankind when it broke God's moral law.[22]

Christians differ in their views on the extent to which individuals' salvation is pre-ordained by God. For example, Calvinism places distinctive emphasis on grace by teaching that individuals are completely incapable of self-redemption, but that sanctifying grace is irresistible. In contrast Catholics, Orthodox Christians, and Arminian Protestants believe that the exercise of free will is necessary to have faith in Jesus.

Trinity

The Trinity is an essential doctrine of mainstream Christianity. Christianity is monotheistic,[11] so the Trinity refers to the teaching that the one God comprises three distinct, eternally co-existing persons: the Father, the Son (incarnate in Jesus Christ) and the Holy Spirit. Together, these three persons are sometimes called the Godhead,[23] although there is no single term in use in Scripture to denote the unified Godhead.[12] In the words of the Athanasian Creed, an early statement of Christian belief, "the Father is God, the Son is God, and the Holy Spirit is God, and yet there are not three Gods but one God."[24] They are distinct from another: the Father has no source, the Son is begotten of the Father, and the Spirit proceeds from the Father. Though distinct, the three persons cannot be divided from one another in being or in operation.

According to this doctrine, God is not divided in the sense that each person has a third of the whole; rather, each person is considered to be fully God. The distinction lies in their relations, the Father being unbegotten; the Son being begotten of the Father; and the Holy Spirit proceeding from the Father and (in Western Christian theology) from the Son. Regardless of this apparent difference, the three "persons" are each eternal and omnipotent.

Trinitarianism denotes Christians who believe in the concept of the Trinity. Almost all Christian denominations and churches hold Trinitarian beliefs. Although the words "Trinity" and "Triune" do not appear in the Bible, beginning in the third century theologians developed the term and concept to facilitate apprehension of the New Testament teachings of God as being Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Since that time, Christian theologians have been careful to emphasize that Trinity does not imply that there are three gods (the antitrinitarian heresy of Tritheism), nor that each hypostasis of the Trinity is one-third of an infinite God (partialism), nor that the Son and the Holy Spirit are beings created by and subordinate to the Father (Arianism). Rather, the Trinity is defined as one God in three persons.[25]

Nontrinitarianism (or antitrinitarianism) refers to theology that rejects the doctrine of the Trinity. Various nontrinitarian views, such as adoptionism or modalism, existed in early Christianity. Contemporary Christian religions that do not share those views on the Trinity include Unitarian Universalism, Jehovah's Witnesses, Mormonism, and Oneness Pentecostal churches.

Eschatology

Eschatology is the study of the end of things, whether the end of an individual life, the end of the age, or the end of the world. The major issues in Christian eschatology are the Tribulation, death and the afterlife, (mainly for Evangelical groups) the Millennium and the following Rapture, the Second Coming of Jesus, Resurrection of the Dead, Heaven, (for liturgical branches) Purgatory, and Hell, the Last Judgment, the end of the world, and the New Heavens and New Earth.

Christians believe that the second coming of Christ will occur at the end of time, after a period of severe persecution (the Great Tribulation). All who have died will be resurrected bodily from the dead for the Last Judgment. Jesus will fully establish the Kingdom of God in fulfillment of scriptural prophecies.[26][27]

Most Christians believe that human beings experience divine judgment and are rewarded either with eternal life in heaven or eternal damnation. This includes the general judgement at the resurrection of the dead as well as the belief (held by Catholics, and most Protestants) in a judgment particular to the individual soul upon physical death.

In the Catholic branch of Christianity, those who die in a state of grace, i.e., without any mortal sin separating them from God, but are still imperfectly purified from the effects of sin, undergo purification through the intermediate state of purgatory to achieve the holiness necessary for entrance into God's presence.[28] Those who have attained this goal are called saints (Latin sanctus, "holy").[29]

Practices

Depending on the specific denomination of Christianity, practices may include baptism, the Eucharist (Holy Communion or the Lord's Supper), prayer (including the Lord's Prayer), confession, confirmation, burial rites, marriage rites and the religious education of children. Most denominations have ordained clergy who lead regular communal worship services.[31]

Christian rites, rituals, and ceremonies are not celebrated in one single sacred language. Many ritualistic Christian churches make a distinction between sacred language, liturgical language, and vernacular language.

Communal worship

Church services of worship typically follow a pattern or form known as liturgy. Frequently a distinction is made between "liturgical" and "non-liturgical" churches based on how elaborate or antiquated the worship; in this usage, churches whose services are unscripted or improvised are described as "non-liturgical."[32] Justin Martyr described second-century Christian liturgy in his First Apology (c. 150) to Emperor Antoninus Pius, and his description remains relevant to the basic structure of Christian liturgical worship:

And on the day called Sunday, all who live in cities or in the country gather together to one place, and the memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read, as long as time permits; then, when the reader has ceased, the president verbally instructs, and exhorts to the imitation of these good things. Then we all rise together and pray, and, as we before said, when our prayer is ended, bread and wine and water are brought, and the president in like manner offers prayers and thanksgivings, according to his ability, and the people assent, saying Amen; and there is a distribution to each, and a participation of that over which thanks have been given, and to those who are absent a portion is sent by the deacons. And they who are well to do, and willing, give what each thinks fit; and what is collected is deposited with the president, who succours the orphans and widows and those who, through sickness or any other cause, are in want, and those who are in bonds and the strangers sojourning among us, and in a word takes care of all who are in need.[33]

Thus, as Justin described, Christians assemble for communal worship typically on Sunday, the day of the resurrection, though other liturgical practices often occur outside this setting. Scripture readings are drawn from the Old and New Testaments, but especially the gospels. Often these are arranged on an annual cycle, using a book called a lectionary. Instruction is given based on these readings, in the form of a sermon or homily. There are a variety of congregational prayers, including thanksgiving, confession, and intercession, which occur throughout the service and take a variety of forms including recited, responsive, silent, or sung.[31] Psalms, hymns, and other worship songs may be sung.

Nearly all forms of worship incorporate the Eucharist. It is reenacted in accordance with Jesus' instruction at the Last Supper when he gave his disciples bread, saying, "This is my body," and gave them wine saying, "This is my blood." And he said to "do this in remembrance of me" (Luke 22:19-20).

Sacraments or ordinances

In Christian belief and practice, a sacrament is a rite, instituted by Christ, that confers grace, constituting a sacred mystery. The term is derived from the Latin word sacramentum, which was used to translate the Greek word for mystery. Views concerning both which rites are sacramental, and what it means for an act to be a sacrament, vary among Christian denominations and traditions.

The two most widely accepted sacraments are Baptism and the Eucharist; however, the majority of Christians also recognize five additional sacraments: Confirmation (Chrismation in the Eastern tradition), Holy Orders (or ordination), Penance (or Confession), Anointing of the Sick, and Matrimony.

Taken together, these are the Seven Sacraments as recognized by churches in the High Church tradition—notably Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, some Lutherans, and Anglicans. Certain denominations of Christianity, such as Anabaptists, use the term "ordinances" to refer to rites instituted by Jesus for Christians to observe. Seven ordinances have been taught in many conservative Mennonite Anabaptist churches, which include "baptism, communion, footwashing, marriage, anointing with oil, the holy kiss, and the prayer covering".[30]

Liturgical calendar

Catholics, Eastern Christians, Lutherans, Anglicans and other traditional Protestant communities frame worship around the liturgical year.[34] The liturgical cycle divides the year into a series of seasons, each with their theological emphases, and modes of prayer, which can be signified by different ways of decorating churches, colors of paraments and vestments for clergy, scriptural readings, themes for preaching, and even different traditions and practices often observed personally or in the home.

Western Christian liturgical calendars are based on the cycle of the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church, and Eastern Christians use analogous calendars based on the cycle of their respective rites. Calendars set aside holy days, such as solemnities which commemorate an event in the life of Jesus, Mary, or the saints, and periods of fasting, such as Lent and other pious events such as memoria, or lesser festivals commemorating saints. Christian groups that do not follow a liturgical tradition often retain certain celebrations, such as Christmas, Easter, and Pentecost: these are the celebrations of Christ's birth, resurrection, and the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Church, respectively. A few denominations make no use of a liturgical calendar.

Symbols

The cross, today one of the most widely recognized symbols, was used by Christians from the earliest times. Tertullian, in his book De Corona, tells how it was already a tradition for Christians to trace the sign of the cross on their foreheads: "At every forward step and movement, at every going in and out, when we put on our clothes and shoes, when we bathe, when we sit at table, when we light the lamps, on couch, on seat, in all the ordinary actions of daily life, we trace upon the forehead the sign."[35] Although the cross was known to the early Christians, the crucifix did not appear in use until the fifth century.[36]

Among the earliest Christian symbols, that of the fish or Ichthys seems to have ranked first in importance, as seen on monuments and tombs from the first decades of the second century. Its popularity seemingly arose from the Greek word ichthys (fish) forming an acrostic for the Greek phrase Iesous Christos Theou Yios Soter (Ἰησοῦς Χριστός, Θεοῦ Υἱός, Σωτήρ) (Jesus Christ, Son of God, Savior), a concise summary of Christian faith.[37]

Other major Christian symbols include the chi-rho monogram, the dove and olive branch (symbolic of the Holy Spirit), the sacrificial lamb (representing Christ's sacrifice), the vine (symbolizing the connection of the Christian with Christ) and many others. These all derive from passages of the New Testament.[36]

Baptism

Baptism is the ritual act, with the use of water, by which a person is admitted to membership of the Church. Beliefs on baptism vary among denominations. Differences occur firstly on whether the act has any spiritual significance. Some, such as the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches, as well as Lutherans and Anglicans, hold to the doctrine of baptismal regeneration, which affirms that baptism creates or strengthens a person's faith, and is intimately linked to salvation. Baptists and Plymouth Brethren view baptism as a purely symbolic act, an external public declaration of the inward change which has taken place in the person, but not as spiritually efficacious. Secondly, there are differences of opinion on the methodology (or mode) of the act. These modes are: by immersion; if immersion is total, by submersion; by affusion (pouring); and by aspersion (sprinkling).[38]

Infant baptism, also called "christening," is the practice of baptizing infants or young children. Most Christians belong to denominations that practice infant baptism.

Prayer

In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus taught the Lord's Prayer, which has been seen as a model for Christian prayer:

When he was standing on a hillside, Jesus explained to his followers how they were to behave as God would wish. The talk has become known as the Sermon on the Mount, and is found in the Gospel of Matthew, chapter 5, 6 and 7. During the talk Jesus taught his followers how to pray and he gave them an example of suitable prayer. Christians call the prayer the Lord's Prayer, because it was taught by the Lord, Jesus Christ. It is also known as the Pattern Prayer as it provides a pattern for Christians to follow in prayer, to ensure that they pray in the way God and Jesus would want.[39]

Other popular forms of Christian prayer include the Rosary (in Roman Catholicism) and the Jesus Prayer (in Eastern Orthodoxy).

Christians may pray to God as a universal creator, or may pray to the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit (or some combination thereof).

Intercessory prayer is prayer offered for the benefit of other people. There are many intercessory prayers recorded in the Bible, including prayers of the Apostle Peter on behalf of sick persons (Acts 9:40) and by prophets of the Old Testament in favor of other people (1Kings 17:19–22). In the Epistle of James, no distinction is made between the intercessory prayer offered by ordinary believers and the prominent Old Testament prophet Elijah (James 5:16–18).

Scriptures

Christianity regards the biblical canon, the Old Testament and the New Testament, as the inspired word of God. The traditional view of inspiration is that God worked through human authors so that what they produced was what God wished to communicate. The Greek word referring to inspiration in 2Timothy 3:16 is theopneustos, which literally means "God-breathed."[40]

Some believe that divine inspiration makes present Bibles inerrant. Others claim inerrancy for the Bible in its original manuscripts, although none of those are extant. Still others maintain that only a particular translation is inerrant, such as the King James Version. Another closely related view is biblical infallibility or limited inerrancy, which affirms that the Bible is free of error as a guide to salvation, but may include errors on matters such as history, geography, or science.

The canon of the Old Testament accepted by Protestant churches, which is only the Tanakh (the canon of the Hebrew Bible), is shorter than that accepted by the Orthodox and Catholic churches which also include the deuterocanonical books which appear in the Septuagint, the Orthodox canon being slightly larger than the Catholic;[41] Protestants regard the latter as apocryphal, important historical documents which help to inform the understanding of words, grammar, and syntax used in the historical period of their conception. Some versions of the Bible include a separate Apocrypha section between the Old Testament and the New Testament.[12] The New Testament, originally written in Koine Greek, contains 27 books which are agreed upon by all major churches.

Some denominations have additional canonical holy scriptures beyond the Bible, including the standard works of the Latter Day Saints and Divine Principle in the Unification Church.[42]

History

Christianity began in the first century after the birth of Jesus as a Judaic sect with Hellenistic influence, in the Roman province of Judaea. The disciples of Jesus spread their faith around the Eastern Mediterranean area, despite significant persecution. The inclusion of Gentiles led Christianity to slowly separate from Judaism in the second century. Emperor Constantine I decriminalized Christianity in the Roman Empire by the Edict of Milan (313), later convening the First Council of Nicaea (325) where Early Christianity was consolidated into what would become the state religion of the Roman Empire (380).

The Church of the East and Oriental Orthodoxy both split over differences in Christology in the fifth century, while the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Catholic Church separated in the East–West Schism (1054). Protestantism split into numerous denominations from the Catholic Church in the Reformation era of the sixteenth century). Following the Age of Discovery (fifteenth–seventeenth century), Christianity expanded throughout the world via missionary work, evangelism, immigration, and extensive trade.

Early Christianity

Apostolic Age

Christianity developed during the first century C.E. as a Jewish Christian sect with Hellenistic influence of Second Temple Judaism.[43] An early Jewish Christian community was founded in Jerusalem under the leadership of the Pillars of the Church, namely James the Just, the brother of Jesus, Peter, and John.[44]

Jewish Christianity soon attracted Gentile God-fearers, posing a problem for its Jewish religious outlook, which insisted on close observance of the Jewish commandments. Paul the Apostle solved this by insisting that salvation by faith in Christ, and participation in his death and resurrection by their baptism, sufficed. At first he persecuted the early Christians, but after a conversion experience he preached to the gentiles, and is regarded as having had a formative effect on the emerging Christian identity as separate from Judaism. Eventually, his departure from Jewish customs would result in the establishment of Christianity as an independent religion.[45]

Ante-Nicene period

This formative period was followed by the early bishops, whom Christians consider the successors of Christ's apostles. From the year 150, Christian teachers began to produce theological and apologetic works aimed at defending the faith. These authors are known as the Church Fathers, and the study of them is called patristics. Notable early Fathers include Ignatius of Antioch, Polycarp, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria, and Origen.

While Proto-orthodox Christianity was becoming dominant, heterodox sects also existed at the same time, which held radically different beliefs. For example, Gnostic Christianity developed a duotheistic doctrine based on illusion and enlightenment rather than forgiveness of sin, which was eventually considered heretical and suppressed by mainstream Christians.

Spread in Roman Empire

Christianity spread to Aramaic-speaking peoples along the Mediterranean coast and also to the inland parts of the Roman Empire and beyond that into the Parthian Empire and the later Sasanian Empire, including Mesopotamia, which was dominated at different times and to varying extents by these empires.[46]

The presence of Christianity in Africa began in the middle of the first century in Egypt and by the end of the secondnd century in the region around Carthage. Important Africans who influenced the early development of Christianity include Tertullian, Clement of Alexandria, Origen of Alexandria, Cyprian, Athanasius, and Augustine of Hippo.

King Tiridates III made Christianity the state religion in Armenia in the early fourth century C.E.

Constantine I was exposed to Christianity in his youth, and throughout his life his support for the religion grew, culminating in baptism on his deathbed. During his reign, state-sanctioned persecution of Christians was ended with the Edict of Toleration in 311 and the Edict of Milan in 313. Constantine was also instrumental in the convocation of the First Council of Nicaea in 325, which sought to address Arianism and formulated the Nicene Creed, which is still used by in Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Lutheranism, Anglicanism, and many other Protestant churches. Nicaea was the first of a series of ecumenical councils, which formally defined critical elements of the theology of the Church, notably concerning Christology.[47] The Church of the East did not accept the third and following ecumenical councils and is still separate today by its successors (Assyrian Church of the East).

Middle Ages

Early Middle Ages

With the decline and fall of the Roman Empire in the West, the papacy became a political player, first visible in Pope Leo's diplomatic dealings with Huns and Vandals.[48] The church also entered into a long period of missionary activity and expansion among the various tribes.

Around 500, Christianity was thoroughly integrated into Byzantine and Kingdom of Italy culture and Benedict of Nursia set out his Monastic Rule, establishing a system of regulations for the foundation and running of monasteries. Monasticism became a powerful force throughout Europe,[48] and gave rise to many early centers of learning, most famously in Ireland, Scotland, and Gaul, contributing to the Carolingian Renaissance of the ninth century.

The Middle Ages brought about major changes within the church. Pope Gregory the Great dramatically reformed the ecclesiastical structure and administration. In the early eighth century, iconoclasm became a divisive issue, when it was sponsored by the Byzantine emperors. The Second Ecumenical Council of Nicaea (787) finally pronounced in favor of icons. In the early tenth century, Western Christian monasticism was further rejuvenated through the leadership of the great Benedictine monastery of Cluny.[48]

High and Late Middle Ages

In the West, from the eleventh century onward, some older cathedral schools became universities (for example, University of Oxford, University of Paris, and University of Bologna). Accompanying the rise of the "new towns" throughout Europe, mendicant orders were founded, bringing the consecrated religious life out of the monastery and into the new urban setting. The two principal mendicant movements were the Franciscans and the Dominicans, founded by Francis of Assisi and Dominic, respectively. Both orders made significant contributions to the development of the great universities of Europe. Another new order was the Cistercians, whose large, isolated monasteries spearheaded the settlement of former wilderness areas. In this period, church building and ecclesiastical architecture reached new heights, culminating in the orders of Romanesque and Gothic architecture and the building of the great European cathedrals.[48]

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and sometimes directed by the Christian Latin Church. From 1095 under the pontificate of Urban II, the First Crusade was launched. These were a series of military campaigns in the Holy Land and elsewhere, initiated in response to pleas from the Byzantine Emperor Alexios I for aid against Turkish expansion. The Crusades ultimately failed to stifle Islamic aggression and even contributed to Christian enmity with the sacking of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade.

The Christian Church experienced internal conflict between the seventh and thirteenth centuries that resulted in a schism between the Latin Church of Western Christianity branch, the now-Catholic Church, and an Eastern, largely Greek, branch (the Eastern Orthodox Church). The two sides disagreed on a number of administrative, liturgical, and doctrinal issues, most prominently Eastern Orthodox opposition to papal supremacy.[49] The Second Council of Lyon (1274) and the Council of Florence (1439) attempted to reunite the churches, but in both cases, the Eastern Orthodox refused to implement the decisions, and the two principal churches remain in schism to the present day.

Beginning around 1184, following the crusade against Cathar heresy, various institutions, broadly referred to as the Inquisition, were established with the aim of suppressing heresy and securing religious and doctrinal unity within Christianity through conversion and prosecution.[48]

Modern era

Protestant Reformation

The fifteenth-century Renaissance brought about a renewed interest in ancient and classical learning. During the Reformation, Martin Luther posted the Ninety-five Theses 1517 against the sale of indulgences. Printed copies soon spread throughout Europe. In 1521 the Edict of Worms condemned and excommunicated Luther and his followers, resulting in the schism of the Western Christendom into several branches.[50]

Other reformers like Zwingli, Oecolampadius, Calvin, Knox, and Arminius further criticized Catholic teaching and worship. These challenges developed into the movement called Protestantism, which repudiated the primacy of the pope, the role of tradition, the seven sacraments, and other doctrines and practices.[50] The Reformation in England began in 1534, when King Henry VIII had himself declared head of the Church of England.

Thomas Müntzer, Andreas Karlstadt and other theologians perceived both the Catholic Church and the confessions of the Magisterial Reformation as corrupted. Their activity brought about the Radical Reformation, which gave birth to various Anabaptist denominations.

Partly in response to the Protestant Reformation, the Catholic Church engaged in a substantial process of reform and renewal, known as the Counter-Reformation or Catholic Reform. The Council of Trent clarified and reasserted Catholic doctrine. During the following centuries, competition between Catholicism and Protestantism became deeply entangled with political struggles among European states.[50]

Meanwhile, the discovery of America by Christopher Columbus in 1492 brought about a new wave of missionary activity. Partly from missionary zeal, but under the impetus of colonial expansion by the European powers, Christianity spread to the Americas, Oceania, East Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa.

Throughout Europe, the division caused by the Reformation led to outbreaks of religious violence and the establishment of separate state churches in Europe. Lutheranism spread into the northern, central, and eastern parts of present-day Germany, Livonia, and Scandinavia. Anglicanism was established in England in 1534. Calvinism and its varieties, such as Presbyterianism, were introduced in Scotland, the Netherlands, Hungary, Switzerland, and France. Arminianism gained followers in the Netherlands and Frisia. Ultimately, these differences led to the outbreak of conflicts in which religion played a key factor. The Thirty Years' War, the English Civil War, and the French Wars of Religion are prominent examples. These events intensified Christian debate on persecution and toleration.[51]

Post-Enlightenment

In the era known as the Great Divergence, when in the West, the Age of Enlightenment and the scientific revolution brought about great societal changes, Christianity was confronted with various forms of skepticism and with certain modern political ideologies, such as versions of socialism and liberalism.[52] Events ranged from mere anti-clericalism to violent outbursts against Christianity, such as the Dechristianization of France during the French Revolution, the Spanish Civil War, and certain Marxist movements, especially the Russian Revolution and the persecution of Christians in the Soviet Union under state atheism.[53]

The combined factors of the formation of nation states, separation of church and state, and ultramontanism, especially in Germany and the Netherlands, often forced Catholic churches, organizations, and believers to choose between the national demands of the state and the authority of the Church, specifically the papacy. This conflict came to a head in the First Vatican Council, and in Germany would lead directly to the Kulturkampf.

Demographics

With over 2 billion adherents split into three main branches of Catholic, Protestant, and Eastern Orthodox, Christianity is the world's largest religion.[54] Christianity is the predominant religion in Europe, the Americas, Oceania, and Sub-Saharan Africa. There are also large Christian communities in other parts of the world, such as Central Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, East Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent.[55]

However, Christianity is declining in some areas. Despite a decline in adherence in the West, Christianity remains the dominant religion in the region, with about 70 percent of that population identifying as Christian.[55]

Churches and denominations

- See also: Ecclesiology and Christian Church

There is a diversity of doctrines and liturgical practices among groups calling themselves Christian. A broad distinction is drawn between Eastern Christianity and Western Christianity, which has its origins in the East–West Schism (Great Schism) of the eleventh century. After these two larger families come distinct branches of Christianity. Most classification schemes list Roman Catholicism, Protestantism, and Orthodox Christianity, with Orthodox Christianity being divided into Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, and the Church of the East. Protestantism is divided into a large and diverse selection of groups, including Baptists, Methodists, Pentecostals, Presbyterians, Reformed Churches, and Unitarians.

Catholic Church

The Catholic Church consists of those particular Churches, headed by bishops, in communion with the pope, the bishop of Rome, as its highest authority in matters of faith, morality, and church governance.[56][49] Like Eastern Orthodoxy, the Catholic Church, through apostolic succession, traces its origins to the Christian community founded by Jesus Christ.[57]

As the world's oldest and largest continuously functioning international institution, it has played a prominent role in the history and development of Western civilization. With more than 1.1 billion baptized members, the Catholic Church is the largest Christian church and represents approximately 50 percent of all Christians.[55] Catholics live all over the world through missions, diaspora, and conversions.

Eastern Orthodox Church

Eastern Orthodox theology is based on holy tradition which incorporates the dogmatic decrees of the seven Ecumenical Councils, the Scriptures, and the teaching of the Church Fathers. Like the Catholic Church, the Eastern Orthodox Church also traces its heritage to the foundation of Christianity through apostolic succession and has an episcopal structure, though the autonomy of its component parts is emphasized, and most of them are national churches. The church teaches that it is the one, holy, catholic and apostolic church established by Jesus Christ in his Great Commission.[58]

As one of the oldest surviving religious institutions in the world, the Eastern Orthodox Church has played a prominent role in the history and culture of Eastern and Southeastern Europe, the Caucasus, and the Near East.[59] The majority of Eastern Orthodox Christians live mainly in Southeast and Eastern Europe, Cyprus, Georgia, and parts of the Caucasus region, Siberia, and the Russian Far East. Over half of Eastern Orthodox Christians follow the Russian Orthodox Church, while the vast majority live within Russia. There are also communities in the former Byzantine regions of Africa, the Eastern Mediterranean, and in the Middle East, as well as many other parts of the world.

Oriental Orthodoxy

The Oriental Orthodox Churches (also called "Old Oriental" churches) are those eastern churches that recognize the first three ecumenical councils—Nicaea, Constantinople, and Ephesus—but reject the dogmatic definitions of the Council of Chalcedon and instead espouse a Miaphysite christology.[60]

The Oriental Orthodox communion consists of six groups: Syriac Orthodox, Coptic Orthodox, Ethiopian Orthodox, Eritrean Orthodox, Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church (India), and Armenian Apostolic churches. These six churches, while being in communion with each other, are completely independent hierarchically.

As some of the oldest religious institutions in the world, the Oriental Orthodox Churches have played a prominent role in the history and culture of Armenia, Egypt, Turkey, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Sudan, Iran, Azerbaijan, parts of the Middle East, and India.[61]

Church of the East

The Church of the East shared communion with those in the Roman Empire until the Council of Ephesus condemned Nestorius in 431. Continuing as a dhimmi community under the Rashidun Caliphate after the Muslim conquest of Persia (633–654), the Church of the East played a major role in the history of Christianity in Asia. It established dioceses and communities stretching from the Mediterranean Sea and today's Iraq and Iran, to India (the Saint Thomas Syrian Christians of Kerala), the Mongol kingdoms in Central Asia, and China during the Tang dynasty (seventh–ninth centuries). In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the church experienced a final period of expansion under the Mongol Empire, where influential Church of the East clergy sat in the Mongol court.

The Assyrian Church of the East, with an unbroken patriarchate established in the seventeenth century, is an independent Eastern Christian denomination which claims continuity from the Church of the East—in parallel to the Catholic patriarchate established in the sixteenth century that evolved into the Chaldean Catholic Church, an Eastern Catholic church in full communion with the Pope. Largely aniconic and not in communion with any other church, it belongs to the eastern branch of Syriac Christianity, and uses the East Syriac Rite in its liturgy.[62] Its main spoken language is Syriac, a dialect of Eastern Aramaic, and the majority of its adherents are ethnic Assyrians, mostly living in Iran, Iraq, Syria, Turkey, India (Chaldean Syrian Church), and in the Assyrian diaspora.

The Ancient Church of the East distinguished itself from the Assyrian Church of the East in 1964 under the leadership of Mar Toma Darmo (d. 1969), and is officially headquartered in the city of Baghdad. It is one of three Assyrian Churches that claim continuity with the historical Church of the East, the others being the Assyrian Church of the East and the Chaldean Catholic Church.

Protestantism

In 1521, the Edict of Worms condemned Martin Luther and officially banned citizens of the Holy Roman Empire from defending or propagating his ideas. This split within the Roman Catholic church is now called the Reformation. Prominent Reformers included Martin Luther, Huldrych Zwingli, and John Calvin. The 1529 Protestation at Speyer against being excommunicated gave this party the name Protestantism. Luther's primary theological heirs are known as Lutherans. Zwingli and Calvin's heirs are far broader denominationally and are referred to as the Reformed tradition.[47] The Anglican churches descended from the Church of England and organized in the Anglican Communion.

Since the Anglican, Lutheran, and the Reformed branches of Protestantism originated for the most part in cooperation with the government, these movements are termed the "Magisterial Reformation". On the other hand, groups such as the Anabaptists, who often do not consider themselves to be Protestant, originated in the Radical Reformation, which though sometimes protected under Acts of Toleration, do not trace their history back to any state church.

The term Protestant also refers to any churches which formed later. In the eighteenth century, for example, Methodism grew out of Anglican minister John Wesley's evangelical revival movement. Several Pentecostal and non-denominational churches, which emphasize the cleansing power of the Holy Spirit, in turn grew out of Methodism. Because Methodists, Pentecostals, and other evangelicals stress "accepting Jesus as your personal Lord and Savior," which comes from Wesley's emphasis on "New Birth," they often refer to themselves as being born-again.[63]

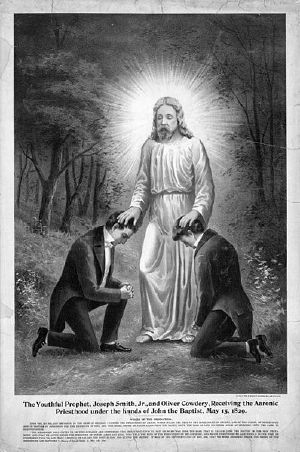

Restorationism

The Second Great Awakening, a period of religious revival that occurred in the United States during the early 1800s, saw the development of a number of unrelated churches. They generally saw themselves as restoring the original church of Jesus Christ rather than reforming one of the existing churches.[47] A common belief held by Restorationists was that the other divisions of Christianity had introduced doctrinal defects into Christianity, known as the Great Apostasy.

Some of the churches originating during this period are historically connected to early nineteenth-century camp meetings in the Midwest and upstate New York. One of the largest churches produced from the movement is the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. American Millennialism and Adventism, which arose from Evangelical Protestantism, influenced the Jehovah's Witnesses movement and, as a reaction specifically to William Miller, the Seventh-day Adventists. Others, including the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Evangelical Christian Church in Canada, and the Churches of Christ, have their roots in the contemporaneous Stone-Campbell Restoration Movement, which was centered in Kentucky and Tennessee.[64]

Ecumenism

Christian groups and denominations have long expressed ideals of being reconciled, and in the twentieth century, Christian ecumenism advanced in two ways. One way was greater cooperation between groups, such as the World Evangelical Alliance founded in 1846 in London or the Edinburgh Missionary Conference of Protestants in 1910, the Justice, Peace and Creation Commission of the World Council of Churches founded in 1948 by Protestant and Orthodox churches, and similar national councils like the National Council of Churches in Australia, which includes Catholics.[47]

The other way was an institutional union with united churches, a practice that can be traced back to unions between Lutherans and Calvinists in early nineteenth-century Germany. Congregationalist, Methodist, and Presbyterian churches united in 1925 to form the United Church of Canada, and in 1977 to form the Uniting Church in Australia. The Church of South India was formed in 1947 by the union of Anglican, Baptist, Methodist, Congregationalist, and Presbyterian churches.[47]

Steps towards reconciliation on a global level were taken in 1965 by the Catholic and Orthodox churches, mutually revoking the excommunications that marked their Great Schism in 1054; the Anglican Catholic International Commission (ARCIC) working towards full communion between those churches since 1970;[47] and some Lutheran and Catholic churches signing the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification in 1999 to address conflicts at the root of the Protestant Reformation.

Cultural influence

The history of the Christendom spans about 1,700 years and includes a variety of socio-political developments, as well as advances in the arts, architecture, literature, science, philosophy, and technology.[44] The Bible has had a profound influence on Western civilization and on cultures around the globe; it has contributed to the formation of law, art, and education.

Historically, Christianity has often been a patron of science and medicine; many Catholic clergy, Jesuits in particular, have been active in the sciences throughout history and have made significant contributions to the development of science.[65] Christianity has had a significant impact on education, as the church created the bases of the Western system of education, and was the sponsor of founding universities in the Western world.[66]

Christianity played a prominent role in the development of Western civilization, particularly in Europe from late antiquity and the Middle Ages.[67] Western culture, throughout most of its history, has been nearly equivalent to Christian culture. The notion of "Europe" and the "Western World" has been intimately connected with the concept of "Christianity and Christendom."

Outside the Western world, Christianity has influenced various cultures, such as in Africa, the Near East, Middle East, East Asia, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent.

Controversies

Criticism

Criticism of Christianity and Christians goes back to the Apostolic Age, with the New Testament recording friction between the followers of Jesus and the Pharisees and scribes (Matthew 15:1–20 and Mark 7:1–23). In the second century, Christianity was criticized by the Jews on various grounds, such as that the prophecies of the Hebrew Bible could not have been fulfilled by Jesus, given that he did not have a successful life.[45]

In more recent times, Nietzsche wrote a series of polemics in the nineteenth century on the against Christianity. While he severely criticized Christianity, he had a high esteem for Jesus, questioning the doctrine of faith in the cross and arguing that Christianity did not reflect Jesus' own teachings.[68] In the twentieth century, the philosopher Bertrand Russell expressed his criticism of Christianity in Why I Am Not a Christian, formulating his rejection of Christianity in the setting of logical arguments.[69]

Contemporary criticism of Christianity includes criticism by Jewish and Muslim theologians of the doctrine of the Trinity, stating that this doctrine in effect assumes that there are three gods, running against the basic tenet of monotheism.[44]

Persecution and violence

Christians are one of the most persecuted religious groups in the world.

A 2019 study, commissioned by the United Kingdom's Secretary of State of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) to investigate global persecution of Christians, found that approximately 80 percent of religiously motivated discrimination worldwide targeted Christians. Such persecution is global, and not limited to Islamic states. Christian persecution was found to be highest in the Middle East, North Africa, India, China, North Korea, and Latin America, among others.[70]

Christians have not only been the victims of persecution, but have also been the perpetrators, even to the level of violence, despite the strong doctrinal and historical imperative against violence contained in Jesus' teachings which promote nonviolence and "love of enemies." However, it has been suggested that all monotheistic religions, including Christianity, are inherently violent because of their exclusivism which inevitably fosters violence against those who are considered outsiders.[71] Specifically the Abrahamic faiths have been guilty of using violence against each other:

The history of religious violence in the West is as long as the historical record of its three major religions, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, with their mutual antagonisms and their struggles to adapt and survive despite the secular forces that threaten their continued existence.[72]

Notes

- ↑ Acts 19:23 Jamieson-Fausset-Brown Bible Commentary Bible Hub. Retrieved July 17, 2024.

- ↑ Acts 19:23 Gill's Exposition Bible Hub. Retrieved July 17, 2024.

- ↑ Philip W. Comfort and Walter A. Elwell (eds.), Tyndale Bible Dictionary (Tyndale House Publishers, 2008, ISBN 978-1414319452).

- ↑ Roger E. Olson, The Mosaic of Christian Belief: Twenty Centuries of Unity and Diversity (IVP Academic, 2016, ISBN 978-0830851256).

- ↑ Frederick K.D. Tayviah, Why Do Bad Things Keep on Happening? (CSS Publishing, 1995, ISBN 978-1556739798).

- ↑ Jaroslav Pelikan, Credo: Historical and Theological Guide to Creeds and Confessions of Faith in the Christian Tradition (Yale University Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0300093889).

- ↑ Council of Ephesus New Advent. Retrieved July 18, 2024.

- ↑ Pope Leo I, Letter to Flavian The Council Of Chalcedon - 451 C.E. Retrieved July 18, 2024.

- ↑ The Athanasian Creed New Advent. Retrieved July 18, 2024.

- ↑ Ron Rhodes, The Complete Guide to Christian Denominations: Understanding the History, Beliefs, and Differences (Harvest House Publishers, 2015, ISBN 978-0736952910).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Linda Woodhead, Christianity: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2014, ISBN 978-0199687749).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Bruce M. Metzger and Michael David Coogan (eds.), Oxford Companion to the Bible (Oxford University Press, 1993, ISBN 978-0195046458).

- ↑ Acts 2:24, Acts 2:31–32, Acts 3:15, Acts 3:26, Acts 4:10, Acts 5:30, Acts 10:40–41, Acts 13:30, Acts 13:34, Acts 13:37, Acts 17:30–31, Romans 10:9, 1Cor 15:15, 1Cor 6:14, 2Cor 4:14, Gal 1:1, Eph 1:20, Col 2:12, 1Thess 1:10, Heb. 13:20, 1Pet 1:3, 1Pet 1:21

- ↑ Acts 1:9–11

- ↑ John 19:30–31 Mark 16:1 Mark 16:6

- ↑ Hank Hanegraaff, Resurrection: The Capstone in the Arch of Christianity (Thomas Nelson, 2002, ISBN 0849942950).

- ↑ John 3:16, John 5:24, John 6:39–40, John 6:47, John 10:10, John 11:25–26, and John 17:3

- ↑ Gal. 3:29

- ↑ N.T. Wright, What Saint Paul Really Said: Was Paul of Tarsus the Real Founder of Christianity? (Eerdmans, 2014, ISBN 978-0802871787).

- ↑ Rom. 8:9,11,16

- ↑ U.S. Catholic Church, Catechism of the Catholic Church (Doubleday, 2003, ISBN 0385508190).

- ↑ L.W. Grensted, A Short History of the Doctrine of the Atonement (Legare Street Press, 2022 (original University of Manchester Press, 1920), ISBN 978-1015495692).

- ↑ J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines (HarperOne, 1978, ISBN 978-0060643348).

- ↑ J.N.D. Kelly, The Athanasian Creed (Adam & Charles Black, 1964, ISBN 978-0713605044).

- ↑ Jürgen Moltmann, M. Kohl (trans.), The Trinity and the Kingdom: The Doctrine of God (SCM Press, 1981, ISBN 978-0334023685).

- ↑ Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologicum, Supplementum Tertiae Partis questions 69 through 99. Retrieved July 19, 2024.

- ↑ John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion (Hendrickson Publishers, 2008, ISBN 978-1598561685).

- ↑ Particular Judgment New Advent. Retrieved July 19, 2024.

- ↑ The Communion of Saints New Advent. Retrieved July 19, 2024.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Rachel Nafziger Hartzler, No Strings Attached: Boundary Lines in Pleasant Places (Resource Publications, 2013, ISBN 1498263860).

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 James F. White, Introduction to Christian Worship (Abingdon Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0687091096).

- ↑ Thomas Arthur Russell, Comparative Christianity: A Student's Guide to a Religion and Its Diverse Traditions (Universal Publishers, 2010, ISBN 978-1599428772).

- ↑ Justin Martyr, First Apology §LXVII. Retrieved July 19, 2024.

- ↑ Frank C. Senn, Introduction to Christian Liturgy (Fortress Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0800698850).

- ↑ Tertullian, De Corona, chapter 3. Retrieved July 19, 2024.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Maurice Dilasser, The Symbols of the Church (Liturgical Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0814625385).

- ↑ Symbolism of the Fish New Advent. Retrieved July 19, 2024.

- ↑ Laurence Hull Stookey, Baptism: Christ's Act in the Church (Abingdon Press, 1982, ISBN 978-0687023646).

- ↑ Anne Jordan, Christianity and Moral Issues (Nelson Thornes, 1999, ISBN 978-0748740390).

- ↑ Henry A. Virkler and Karelynne Gerber Ayayo, Hermeneutics: Principles and Processes of Biblical Interpretation (Baker Academic, 2007, ISBN 978-0801031380).

- ↑ S.T. Kimbrough, Orthodox And Wesleyan Scriptural Understanding And Practice (St Vladimir's Seminary Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0881413014).

- ↑ John Bowker, The Message and the Book: Sacred Texts of the World's Religions (Yale University Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0300192339).

- ↑ Stephen Benko, Pagan Rome and the Early Christians (Indiana University Press, 1986, ISBN 978-0253203854).

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Alister E. McGrath, Christianity: An Introduction (Wiley-Blackwell, 2015, ISBN 978-1118465653).

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 James D.G. Dunn, Jews and Christians: The Parting of the Ways, A.D. 70 to 135 (Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1999, ISBN 978-0802844989).

- ↑ Geoffrey de Ste. Croix, Michael Whitby and Joseph Streeter (eds.), Christian Persecution, Martyrdom and Orthodoxy (Oxford University Press, 2006, ISBN 978-0199278121).

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 47.4 47.5 John McManners (ed.), The Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity (Oxford University Press, 1990, ISBN 978-0198229285).

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 48.3 48.4 Justo L. González, The Story of Christianity (HarperOne, 2010, ISBN 978-0061855887).

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Eamon Duffy, Saints and Sinners: A History of the Pope (Yale University Press, 2015, ISBN 978-0300206128).

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 Edith Simon, Great Ages of Man: The Reformation (Time-Life, 1967, ISBN 0900658320).

- ↑ John Coffey, Persecution and Toleration in Protestant England 1558-1689 (Longman Pub Group, 2000, ISBN 978-0582304659).

- ↑ Michael Novak, Catholic Social Thought and Liberal Institutions: Freedom with Justice (Routledge, 1988, ISBN 978-0887387630).

- ↑ Geoffrey Blainey, A Short History of Christianity (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2015, ISBN 978-1442252462).

- ↑ The Global Religious Landscape Pew Research Center, December 18, 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2024.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 Global Christianity Pew Research Center, December 1, 2011. Retrieved July 20, 2024.

- ↑ Pope Paul VI, Lumen Gentium November 21, 1964 . Retrieved July 20, 2024.

- ↑ Edward Norman, The Roman Catholic Church: An Illustrated History (Thames & Hudson, 2010, ISBN 0500287090).

- ↑ John Meyendorff, Byzantine Theology: Historical Trends and Doctrinal Themes (Fordham University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0823209675).

- ↑ Timothy Ware, The Orthodox Church: An Introduction to Eastern Christianity (Penguin Books, 2015, ISBN 978-0141980638).

- ↑ Ed Hindson and Dan Mitchell, The Popular Encyclopedia of Church History (Harvest House Publishers, 2013, ISBN 978-0736948067).

- ↑ John Meyendorff, Imperial Unity and Christian Divisions: The Church 450-680 C.E. (St Vladimirs Seminary Press, 2011, ISBN 978-0881410556).

- ↑ Christoph Baumer, Church of the East: An Illustrated History of Assyrian Christianity (I.B.Tauris, 2016, ISBN 1784536830).

- ↑ Mark A. Noll, Protestantism: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2011, ISBN 978-0199560974).

- ↑ J. Gordon Melton (ed.), Melton's Encyclopedia of American Religions (Gale Research Inc, 2016, ISBN 978-1414406879).

- ↑ Rodney Stark, For the Glory of God: How Monotheism Led to Reformations, Science, Witch-Hunts and the End of Slavery (Princeton University Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0691119502).

- ↑ Hastings Rashdall, The Universities of Europe in the Middle Ages (Cambridge University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-1108018104).

- ↑ Carlton Hayes, Christianity and Western Civilization (Praeger, 1983, ISBN 0313239622).

- ↑ Tom Stern (ed.), The New Cambridge Companion to Nietzsche (Cambridge University Press, 2019, ISBN 1316613860).

- ↑ Bertrand Russell, Why I Am Not a Christian (Touchstone, 1967, ISBN 978-0671203238).

- ↑ Philip Mounstephen, Final Report and Recommendations Bishop of Truro's Independent Review for the Foreign Secretary of FCO Support for Persecuted Christians July 2019. Retrieved July 19, 2024.

- ↑ Regina M. Schwartz, The Curse of Cain: The Violent Legacy of Monotheism (University of Chicago Press, 1997, ISBN 0226741990).

- ↑ Eric W. Hickey, Encyclopedia of Murder and Violent Crime (SAGE Publications, Inc, 2003, ISBN 978-0761924371).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Baumer, Christoph. Church of the East: An Illustrated History of Assyrian Christianity. I.B.Tauris, 2016. ISBN 1784536830

- Benko, Stephen. Pagan Rome and the Early Christians. Indiana University Press, 1986. ISBN 978-0253203854

- Blainey, Geoffrey. A Short History of Christianity. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2015. ISBN 978-1442252462

- Bowker, John. The Message and the Book: Sacred Texts of the World's Religions. Yale University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0300192339

- Calvin, John, Institutes of the Christian Religion. Hendrickson Publishers, 2008. ISBN 978-1598561685

- Coffey, John. Persecution and Toleration in Protestant England 1558-1689. Longman Pub Group, 2000. ISBN 978-0582304659

- Comfort, Philip W., and Walter A. Elwell (eds.). Tyndale Bible Dictionary. Tyndale House Publishers, 2008. ISBN 978-1414319452

- Dilasser, Maurice. The Symbols of the Church. Liturgical Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0814625385

- Duffy, Eamon. Saints and Sinners: A History of the Pope. Yale University Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0300206128

- Dunn, James D.G. Jews and Christians: The Parting of the Ways, A.D. 70 to 135. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1999. ISBN 978-0802844989

- González, Justo L. The Story of Christianity. HarperOne, 2010. ISBN 978-0061855887

- Grensted, L.W. A Short History of the Doctrine of the Atonement. Legare Street Press, 2022 (original University of Manchester Press, 1920). ISBN 978-1015495692

- Hanegraaff, Hank. Resurrection: The Capstone in the Arch of Christianity. Thomas Nelson, 2002. ISBN 0849942950

- Hayes, Carlton. Christianity and Western Civilization. Praeger, 1983. ISBN 0313239622

- Hindson, Ed, and Dan Mitchell. The Popular Encyclopedia of Church History. Harvest House Publishers, 2013. ISBN 978-0736948067

- Jordan, Anne. Christianity and Moral Issues. Nelson Thornes, 1999. ISBN 978-0748740390

- Kelly, J.N.D. The Athanasian Creed. Adam & Charles Black, 1964. ISBN 978-0713605044

- Kelly, J.N.D. Early Christian Doctrines. HarperOne, 1978. ISBN 978-0060643348

- Kimbrough, S.T. Orthodox And Wesleyan Scriptural Understanding And Practice. St Vladimir's Seminary Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0881413014

- McGrath, Alister E. Christianity: An Introduction. Wiley-Blackwell, 2015. ISBN 978-1118465653

- McManners, John (ed.). The Oxford Illustrated History of Christianity. Oxford University Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0198229285

- Melton, J. Gordon (ed.). Melton's Encyclopedia of American Religions. Gale Research Inc, 2016. ISBN 978-1414406879

- Metzger, Bruce M., and Michael David Coogan (eds.). Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford University Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0195046458

- Meyendorff, John. Imperial Unity and Christian Divisions: The Church 450-680 C.E.. St Vladimirs Seminary Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0881410556

- Meyendorff, John. Byzantine Theology: Historical Trends and Doctrinal Themes. Fordham University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0823209675

- Moltmann, Jürgen, M. Kohl (trans.). The Trinity and the Kingdom: The Doctrine of God. SCM Press, 1981. ISBN 978-0334023685

- Nafziger Hartzler, Rachel. No Strings Attached: Boundary Lines in Pleasant Places. Resource Publications, 2013. ISBN 1498263860

- Noll, Mark A. Protestantism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0199560974

- Norman, Edward. The Roman Catholic Church: An Illustrated History. Thames & Hudson, 2010. ISBN 0500287090

- Novak, Michael. Catholic Social Thought and Liberal Institutions: Freedom with Justice. Routledge, 1988. ISBN 978-0887387630

- Olson, Roger E. The Mosaic of Christian Belief: Twenty Centuries of Unity and Diversity. IVP Academic, 2016. ISBN 978-0830851256

- Pelikan, Jaroslav. Credo: Historical and Theological Guide to Creeds and Confessions of Faith in the Christian Tradition. Yale University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0300093889

- Rashdall, Hastings. The Universities of Europe in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1108018104

- Rhodes, Ron. The Complete Guide to Christian Denominations: Understanding the History, Beliefs, and Differences. Harvest House Publishers, 2015. ISBN 978-0736952910

- Russell, Bertrand. Why I Am Not a Christian. Touchstone, 1967. ISBN 978-0671203238

- Russell, Thomas Arthur. Comparative Christianity: A Student's Guide to a Religion and Its Diverse Traditions. Universal Publishers, 2010. ISBN 978-1599428772

- Schwartz, Regina M. The Curse of Cain: The Violent Legacy of Monotheism. University of Chicago Press, 1997. ISBN 0226741990

- Senn, Frank C. Introduction to Christian Liturgy. Fortress Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0800698850

- Simon, Edith. Great Ages of Man: The Reformation. Time-Life, 1967. ISBN 0900658320

- Stark, Rodney. For the Glory of God: How Monotheism Led to Reformations, Science, Witch-Hunts and the End of Slavery. Princeton University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0691119502

- Ste. Croix, Geoffrey de, Michael Whitby and Joseph Streeter (eds.). Christian Persecution, Martyrdom and Orthodoxy. Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0199278121

- Stern, Tom (ed.). The New Cambridge Companion to Nietzsche. Cambridge University Press, 2019. ISBN 1316613860

- Stookey, Laurence Hull. Baptism: Christ's Act in the Church. Abingdon Press, 1982. ISBN 978-0687023646

- Tayviah, Frederick K.D. Why Do Bad Things Keep on Happening? CSS Publishing, 1995. ISBN 978-1556739798

- U.S. Catholic Church. Catechism of the Catholic Church (Doubleday, 2003, ISBN 0385508190

- Virkler, Henry A., and Karelynne Gerber Ayayo. Hermeneutics: Principles and Processes of Biblical Interpretation. Baker Academic, 2007. ISBN 978-0801031380

- Ware, Timothy. The Orthodox Church: An Introduction to Eastern Christianity. Penguin Books, 2015. ISBN 978-0141980638

- White, James F. Introduction to Christian Worship. Abingdon Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0687091096

- Woodhead, Linda. Christianity: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2014. ISBN 978-0199687749

External links

All links retrieved July 3, 2024.

- Christianity BBC

- Christianity.com

- Christianity World History Encyclopedia

- Christianity History.com

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.