Hell

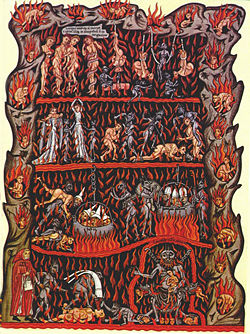

In many world religions, the concept of Hell refers to a literal or symbolic place (or sometimes an existential condition) of damnation where the wicked and unrighteous are punished for their transgressions. The concept of hell is prevalent in many religions although its exact description varies from one religion to another. In traditional Christianity, Islam, and the popular imagination, hell is frequently depicted as a fiery pit located underground where souls are tormented by their past sins and demonic forces. Alternatively, hell has been described (e.g., in Dante's Inferno) as a freezing cold and despondently gloomy place.

Many moderns describe hell as an existential or psychological state (or condition) of the soul. Modern literary understandings of hell often depict it abstractly, as a state of loss rather than as fiery torture that is literally under the ground. Thus, hell can be seen as the complete and final separation of God's love and mercy from sinners who have rejected his moral standards of goodness and have chosen to live a rebellious life of sin. In this light, the actions which supposedly result in one's soul being sent to Hell (i.e. the so called "sins") are precisely those actions that in everyday life cause those states of mind. Hell in the afterlife is but an intensification of the pangs of hell on earth, intensified because the material props of a self-centered life have been removed.

Another issue is whether or not hell is eternal. Religions with a linear view of history typically depict hell as an endless, infinite abyss; conversely, religions with a cyclic view of history often depict hell as an intermediary period between incarnations (for example, the Chinese Di Yu or the Buddhist Naraka). The widespread notion of hell as purgatory is helpful in reconciling the justice of God with his ultimate mercy upon his children.

Despite these variations, the common ground among the descriptions is a place of estrangement and alienation from divinity, which translates into unbearable pain and suffering.

Etymology

The origin of the English word "hell" comes from the Germanic language. Originally, "hel" meant "to cover." The word was also used to designate the goddess of the Norse underworld (Niflheim) and daughter of Loki.

In Christianity, the word "hell"—in Latin, infernus, infernum, inferi; in Greek, ᾍδης (Hades); in Hebrew, שאול (Sheol)—is used in scripture and the Apostles' Creed to refer to the abode of all the dead, whether righteous or evil, unless or until they are admitted to heaven.[1]

Religious accounts

Judaism

The Jewish equivalent of hell is Gehenna, which is described as a fiery place of torment. The word “Gehenna” originates from the Hebrew גי(א)-הינום (Gêhinnôm) meaning the "Valley of Hinnom's son"—a real place outside the city walls of Jerusalem, where child sacrifices were once made to the idol Moloch, and bodies of executed criminals and garbage were once dumped. Fires were kept burning in the valley to keep down the stench. Consequently, Gehenna became associated with abomination of child sacrifice and the horror of burning flesh.

However, Gehenna in Judaism is not exactly hell per se, but a sort of Purgatory where one is judged according to their life's deeds. The Kabbalah describes it as a "waiting room" (commonly translated as an "entry way") for all souls (not just the wicked). The overwhelming majority of rabbinic thought maintains that people are not in Gehenna forever; the longest that one can be there is said to be 12 months, however there has been the occasional noted exception. Some consider it a spiritual forge where the soul is purified for its eventual ascent to Olam Habah (heb. עולם הבא; lit. "The world to come," often viewed as analogous to Heaven). This is also mentioned in the Kabbalah, where the soul is described as breaking, like the flame of a candle lighting another: the part of the soul that ascends being pure and the "unfinished" piece being reborn.

Ancient Greek religion

Another source for the idea of Hell is the Greek and Roman Tartarus, a place in which conquered gods, men, and other spirits were punished. Tartarus formed part of Hades in both Greek mythology and Roman mythology, but Hades also included Elysium, a place for the reward for those who lead virtuous lives, while others spent their afterlife in the asphodels fields. Like most ancient (pre-Christian) religions, the underworld was not viewed as negatively as it is in Christianity and Islam.

When the Hebrew Bible was translated into Greek (see Septuagint), the word that was used to designate the gloomy afterlife was not "hell" but "hades." The Jews preferred the word "hades" as the best translation of the Hebrew word "Sheol." In early Judaism, "Sheol" referred to the comfortless place beneath the earth, where both slave and king, pious and wicked went after death to sleep in silence and oblivion in the dust (Isaiah 38:18; Psalms 6:5, 88:3–12; Job 7:7–10, 3:11–19; Genesis 2:7, 3:19). By the first century, Jews had come to believe that those in Sheol awaited the resurrection either in comfort (in the bosom of Abraham) or in torment. This belief is reflected in the later Jewish concept of a fiery Gehenna, which contrasts with Sheol.

The New Testament (written in Greek) also uses "hades" to mean the abode of the dead (sheol). Western Christians, who do not share a concept of "hades" with the Eastern Orthodox, have traditionally translated "Sheol" (and "hades") as "hell." Unlike hell, however, Sheol is not associated with Satan.

It is likely that the in the course of history, older conceptions of Hades as the generalized abode of the dead differentiated into heaven and hell. This can be explained as due to the greater availability of salvation in the newer mystery religions that spread throughout the Hellenistic world, which advocated a clear distinction between the abodes of light and darkness, as well as in Judaism with the doctrine of the martyrs enjoying eternal blessedness; hence conceptions of hell as a dark and terrifying place developed in tandem with belief in bright abodes as the dwellings of the righteous.

Christianity

Most Christians see hell as the eternal punishment for unrepentant sinners, as well as for the Devil and his demons. As opposed to the concept of Purgatory, damnation to hell is considered final and irreversible. Various interpretations of the torment of hell exist, ranging from fiery pits of wailing sinners to lonely isolation from God's presence.

Most Christians believe that damnation occurs immediately upon death (particular judgment); others believe that it occurs after Judgment Day. It was once said that virtuous unbelievers (such as pagans or members of divergent Christian denominations) are said to deserve hell on account of original sin, and even unbaptized infants are sometimes said to be damned. Exceptions, however, are often made for those who have failed to accept Jesus Christ but have extenuating circumstances (youth not having heard the Gospel, mental illness, etc.). However, attitudes toward hell and damnation have softened over the centuries (for example, see Limbo).

Several Christian denominations reject the traditional concept of hell altogether. Seventh-day Adventists and Jehovah's Witnesses do not believe in hell. They teach that souls in the grave remain asleep until the final judgment, at which time the righteous will be resurrected to heaven and the wicked will simply be annihilated. Unitarian-Universalists see the traditional belief in hell as incompatible with a God of love—inasmuch as God is sent to send sinners there to suffer eternally. They advocate universal salvation, whereby Christ intercedes to save the souls of everyone, even those living in hell.

Modern Christian understandings of hell depict it as the condition of being separated from God's love. Having accepted Jesus Christ and received remissions of sins while on earth opens the gate to receiving God's love, and hence entry to the realms of Paradise. On the other hand, atheists, nominal Christians whose belief is only conceptual, and hypocrites who profess faith but act in the contrary manner, are among those who dwell in hell. However, the faithful of other religions as well as people of good conscience do not dwell in hell but rather in the higher realms appropriate to their belief systems. The judgment leading to hell is self-made, as the newly-departed spirit finds his or her own level with others of similar nature. The realms of hell are populated by people whose character is primarily self-centered. The development during earthly life of a character of altruism or of selfishness is the dividing line that determines whether one will go to heaven or hell.

The predominant Christian view is of an eternal hell, from which escape is impossible. An alternative view that hell is eternal, but not necessarily so, has been proposed by a number of Christian writers. For example, C. S. Lewis suggested the possibility that spirits in hell can be induced to repentance, and thereby be raised to a higher realm. This view is also held by many spiritualists, supported by testimonies and stories of souls whose mission it is to travel to the hells and rescue spirits for whom hell's torments have softened their hearts.[2]

Islam

The Islamic view of hell is called Jahannam (in Arabic: جهنم), which is contrasted to jannah, the garden-like Paradise enjoyed by righteous believers. In the Qur'an, the holy book of Islam, there is literal descriptions of the condemned in a fiery Hell. Hell is split into many levels depending on the actions taken in life, where punishment is allotted according to the amount of evil perpetrated. The Qur'an also says that some of those who are damned to hell are not damned forever, but instead reside there for an indefinite period of time. When Judgment Day comes, the formerly damned will be judged as to whether or not they may enter into Paradise. In any case, it is indicated that punishment in Hell is not meant to last eternally, but instead serves as a basis for spiritual rectification.[3]

Chinese religions

The structure of hell is remarkably complex in many Chinese religions. The ruler of hell has to deal with politics, just as human rulers do. Hell is the subject of many folk stories and in many cases people in hell are able to die again. In some folk stories, a sinner revives from the dead only to writhe and groan as he testifies to his appalled neighbors about the torments he has been suffering in hell. In a Chinese funeral, they burn many Hell Bank Notes for the dead. With this Hell money, the dead person can bribe the ruler of Hell, and spend the rest of the money either in Hell or in Heaven.

The Chinese depiction of hell does not necessarily involve a vast duration of suffering for those who enter Hell, nor does it mean that person is bad. For some, Hell is similar to a present-day passport or immigration control station in so far as a person may be held up there before continuing their spiritual journey. Other depictions follow the Buddhist tradition, seeing Hell as a purgatory where the spirits suffer in recompense for their earthly crimes.

Hinduism

In Hinduism, there are contradictions as to whether or not there is a hell (referred to as Nark in Hindi). For some, it is a metaphor for human conscience, where as for others it is a real place. It is believed that people who commit paap (sin) go to hell and have to go through the punishments in accordance to the sins they committed (even if they have been fundamentally good). For example, the Mahabharata states that both the Pandavas and the Kauravas went to hell. Thus, the heroes of the Mahabharata, who symbolized righteousness, still went to hell because of their past sins. However, in contrast to the typical Western view of hell as a place of eternal suffering, in Hinduism hell is seen as a temporary stop in the cycle of reincarnation.

According to Hindu lore, the god Yama, the god of death, is also said to be the king of hell. The Garuda Purana gives a detailed account of hell, its features, and the different punishment for most crimes (analogous to a modern-day penal code). The detailed accounts of all the sins committed by an individual are supposed to be kept by Chitragupta, who is the record keeper in Yama's court. Chitragupta reads out the sins committed and Yama orders the appropriate punishments to be given. These punishments include dipping in boiling oil, burning in fire, torture using various weapons, etc. However, individuals who finish their quota of the punishments are reborn according to their karma. If one has led a generally pious life, one ascends to Heaven, or Swarga after a brief period of expiation in hell.[4]

Buddhism

As diverse as other religions, there are many beliefs about hell in Buddhism.

Most of the schools of thought, Theravāda, Mahāyāna, and Vajrayāna acknowledge several hells, which are places of great suffering for those who commit evil actions, such as cold hells and hot hells. Like all the different realms within cyclic existence, an existence in hell is temporary for its inhabitants. Those with sufficiently negative karma are reborn there, where they stay until their specific negative karma has been used up, at which point they are reborn in another realm, such as that of humans, of hungry ghosts, of animals, of asuras, of devas, or of Naraka (Hell) all according to the individual's karma.

There are a number of modern Buddhists, especially among Western schools, who believe that hell is only a state of mind. In a sense, a bad day at work could be hell, and a great day at work could be heaven. This has been supported by some modern scholars who advocate the interpretation of such metaphysical portions of the scriptures symbolically rather than literally.

Bahá'í Faith

The Bahá'í Faith agrees with modern Christian views in regarding the traditional descriptions of hell as a specific place to be symbolic language. Instead the Bahá'í writings describe hell as a "spiritual condition" where remoteness from God is defined as hell; conversely heaven is seen as a state of closeness to God. The soul in the afterlife retains its consciousness and individuality and remembers its physical life; the soul will be able to recognize other souls and communicate with them.[5]

Hell in literature and popular culture

In Western religious iconography and popular culture, Hell is often depicted as a fiery place underground where the devil lives. It also is thought to be inhabited by the souls of dead people and by demons who torment the damned. Christian theologians portray Hell as the abode of the fallen angel Lucifer (also known as Satan and the Devil). The devil is seen as the ruler of Hell and is popularly portrayed as a creature that carries a pitchfork, has red skin, horns on his head, a black goatee beard, and a long, thin tail with a triangle-shaped barb on it. Hell itself is described as a domain of boundless torment and the absolute, ultimate worst-case-scenario, per se.

Many of the great epics of European literature include episodes that occur in Hell. In the Roman poet Virgil's Latin epic, the Aeneid, Aeneas descends into Dis (the underworld) to visit his father's spirit. The underworld is only vaguely described, with one unexplored path leading to the punishments of Tartarus, while the other leads through Erebus and the Elysian Fields.

Dante Alighieri's The Divine Comedy is a classic inspiration for modern images of hell. In this work, set in the year 300, Dante employed the conceit of taking Virgil as his guide through Inferno (and then, in the second canticle, up the mountain of Purgatorio). Virgil himself is not condemned to Hell in Dante's poem but is rather, as a virtuous pagan, confined to Limbo just at the edge of Hell. The geography of Hell is very elaborately laid out in this work, with nine concentric rings leading deeper into the Earth and deeper into the various punishments of Hell, until, at the center of the world, Dante finds Satan himself trapped in the frozen lake of Cocytus. A small tunnel leads past Satan and out to the other side of the world, at the base of the Mount of Purgatory.

John Milton's Paradise Lost (1668) opens with the fallen angels, including their leader Satan, waking up in Hell after having been defeated in the war in heaven and the action returns there at several points throughout the poem. The nature of Hell as a place of punishment, as portrayed by Dante, is not explored here; instead, Hell is the abode of the demons, and the passive prison from which they plot their revenge upon Heaven through the corruption of the human race.

C.S. Lewis's The Great Divorce (1945) borrows its title from William Blake's Marriage of Heaven and Hell (1793) and its inspiration from the Divine Comedy as the narrator is likewise guided through Hell and Heaven. Hell is portrayed here as an endless, desolate twilight city upon which night is imperceptibly sinking. The night is actually the Apocalypse, and it heralds the arrival of the demons after their judgment. Before the night comes, anyone can escape Hell if they leave behind their former selves and accept Heaven's offer, and a journey to Heaven reveals that Hell is infinitely small; it is nothing more or less than what happens to a soul that turns away from God and into itself.

One modern symbolic interpretation of Hell was portrayed in the 1998 Hollywood film, What Dreams May Come, based on the eponymous novel by Richard Matheson. In the film, the actions that result in the soul being sent to hell are precisely those actions in everyday life that cause the mind pain and suffering. The state of the mind's pain and suffering is the basis of hell. Thus, while hell is the abode of spirits who have rejected God's goodness—such as the suicide in the film, it is the suicide's depressed state of mind which dominates her thoughts and keeps her trapped in that place. Her husband thus can rescue her from hell by opening her mind to the fact that she is loved above all.

Vernacular usage

The word "Hell" used away from its religious context was long considered to be profanity, particularly in North America. Though its use was commonplace in everyday speech and on television by the 1970s, many people in the United States still consider it somewhat rude or inappropriate language, particularly involving children.[6] Many, particularly among religious circles and in certain sensitive environments, still avoid casual usage of the word.

An example of the common use of “hell” in daily language is the saying "a cold day in hell.” This statement hinges on the paradox that most imagery of hell depicts it as hot and fiery, such as in the Bible in Revelation, where sinners are cast into a lake of fire. Therefore, an event that will transpire “on a cold day in hell” will never occur. Similar or related phrases include: “over my dead body,” “when hell freezes over,” “a snowball's chance in hell,” “when the devil goes ice-skating,” and “when pigs fly.” Still, the phrase "cold as hell" is understood to describe something very cold.

Interestingly, Cocytus, the bottom circle of Hell, which held traitors, in Dante's The Divine Comedy, is depicted as an ice-covered lake.

Notes

- ↑ Paragraph 1. Christ Descended into Hell, 633, in Catechism of the Catholic Church, Section 2: The Profession of the Christian Faith; Chapter 2: I Believe in Jesus Christ, the Only Son of God; Article 5: “He Descended into Hell on the Third Day He Rose Again.” Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- ↑ For example, see Franchezzo, A Wanderer in the Spirit Lands, transcribed by A. Farnese. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- ↑ William C. Chittick, Imaginal Worlds: Ibn al-‘Arabī and the Problem of Religious Diversity (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994); see Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyyah, Hādī al-Arwāh, ed. M. ibn Ibrāhīm al-zaghlī (Al-Dammām, Saudi Arabia: Ramādī lil-Nashr, 1997).

- ↑ Vedic Knowledge Online, Vedic cosmology – planetarium. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- ↑ Franaz Ma’sumian, Life After Death: A Study of the Afterlife in World Religions (Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 1995 ISBN 1851680748).

- ↑ Michael A. Fuoco and Eleanor Chute, Girl suspended for saying h-e-double-hockey-sticks, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, February 5, 2004. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Chittick, William C. Imaginal Worlds: Ibn al-‘Arabī and the Problem of Religious Diversity. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1994.

- Ma’sumian, Franaz. Life After Death: A Study of the Afterlife in World Religions. Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 1995. ISBN 1851680748

External links

All links retrieved June 25, 2024.

- Hell as non-eternal (Universalist study)

- Dying, Yamaraja, and Yamadutas at Vedic Knowledge Online

- Example of Buddhist hells

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Entry on Heaven and Hell in Christian Thought

- The Jewish View of Hell

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.