Atheism

Atheism (from Greek: a + theos + ismos "not believing in god") refers in its broadest sense to a denial of theism (the belief in the existence of a single deity or deities). Atheism has many shades and types. Some atheists strongly deny the existence of God (or any form of deity) and attack theistic claims. Yet certainty as to the non-existence of God is as much a belief as is religion and rests on equally unprovable claims. Just as religious believers range from the ecumenical to the narrow-minded, atheists range from those for whom it is a matter of personal philosophy to those who are militantly hostile to religion.

Atheism often buttresses its case on science, yet many modern scientists, far from being atheists, have argued that science is not incompatible with theism.

Some traditional religious belief systems are said to be "atheist" or "non-theist," but this can be misleading. While Jainism technically can be described as philosophically materialist (and even this is subtle vis-à-vis the divine), the claim about Buddhism being atheistic is more difficult to make. Metaphysical questions put to the Buddha about whether or not God exists received from him one of his famous "silences." It is inaccurate to deduce from this that the Buddha denied the existence of God. His silence had far more to do with the distracting nature of speculation and dogma than it had to do with the existence or non-existence of God.

Many people living in the West have the impression that atheism is on the rise around the world, and that the belief in God is being replaced with a more secular-oriented worldview. However, this view is not confirmed. Studies have consistently shown that contrary to popular assumptions, religious membership is actually increasing globally.

The Rationale of Atheism

Atheism is a belief that is held for a variety of reasons.

Logical reasons

Some atheists base their stance on philosophical grounds, arguing that their position is based on logical rejection of theistic claims. Indeed, many atheists claim that their view is merely the absence of a certain belief, suggesting that the burden of proving God's existence is upon theists. In this line of thought, it follows that if theism's arguments can be refuted, non-theism becomes the default position. Many atheists have argued for centuries against the most popular "proofs" of God's existence, noting problems in the theist lines of reasoning. Atheists who attack specific forms of theism often claim it as being self-contradictory. One of the most common arguments against the existence of the Christian God is the problem of evil, which Christian apologist William Lane Craig has referred to as "atheism's killer argument." This line of reasoning claims that the presence of evil in the world is logically inconsistent with the existence of an omnipotent and benevolent God. Instead, atheists claim it is more coherent to conclude that God does not exist than to believe that He/She does exist but readily allows the promulgation of evil.

A form of atheism known as "ignosticism," asserts that the question of whether or not deities exist is inherently meaningless. It is a popular view among many logical positivists such as Rudolf Carnap and A. J. Ayer, who claim that talk of gods is literally nonsensical. For them, theological statements (such as those affirming god's existence) cannot have any truth value, since they lack falsifiability. This refers to the fact that claims of transcendence and of metaphysical properties cannot be tested by empirical means and must therefore be rejected as null hypotheses. In Language, Truth and Logic, Ayer stated that theism, atheism and agnosticism were equally meaningless terms, insofar as they treat the question of the existence of God as a real question. However, despite Ayer's criticism of atheism as a concept (perhaps using the definition typically associated with strong atheism), ignosticism is still considered as a form of atheism in most classifications of religious thought.

Scientific reasons

As a further development of the rationalist position, many feel that theories of divine creation blatantly conflict with modern science, especially evolution. For some atheists, this conflict is reason enough to reject theism. Evolutionary science, supported by a large body of paleontological and genomic evidence and accepted by the overwhelming majority of biologists, describes how complex life has developed through a slow process of random mutation and natural selection. It is now known that humans share 98 percent of our genetic code with chimpanzees, 90 percent with mice, 21 percent with roundworms, and seven percent with the bacterium E. coli. This humbling perspective is quite different from that of most theistic traditions, such as the Abrahamic religions, in which humans are thought to be created "in God's image" and are existentially distinguished from the other "beasts of the Earth." Similarly, astronomical facts, such as the recognition of Earth's Sun as only one undistinguished star among billions in the Milky Way, are seen by some atheists as rendering implausible the proposition that this universe was created with mankind in mind. Finally, some atheists argue that religion emerged as a pseudo-scientific explanation for natural phenomena and that, with the progress of human scientific endeavor, these etiological myths have been rendered unnecessary.

All this said, it is also true that there are many scientists, Newton and Einstein among them, who do not believe that science is incompatible with the existence of God. Darwinian evolution, for example, can be understood as a method God developed for the propagation of life.

Personal and Practical reasons

In addition to using philosophical arguments, there are those atheists who cite social, psychological, and practical reasons for their beliefs. Many people are atheists not as a result of philosophical deliberation, but rather because of the means by which they were brought up or educated. Some people are atheists at least partly because of growing up in an environment where atheism is relatively common, such as those who are raised by atheist parents. Some people are led to atheism by unpleasant experiences with their inherited traditions.

Some atheists claim that their beliefs have positive practical effects on their lives. For instance, atheism may allow one to open their mind to a wide variety of perspectives and worldviews since they are not committed to dogmatic beliefs. However, since rigidly-held atheism may be a dogmatic belief, those with an open mind are more likely to be agnostics. Such atheists may hold that searching for explanations through natural science can be more beneficial than searching through faith, the latter of which often draws irreconcilable dividing lines between individuals with different beliefs.

Typology of atheism

The first attempts to define or develop a typology annotating the varieties of atheism occurred in religious apologetics, which typically depicted atheism as a licentious belief system. Regardless, a diversity of atheist opinion has been recognized at least since Plato, and common distinctions have been established between practical atheism and contemplative or speculative atheism. Practical atheism was said to be caused by moral failure, hypocrisy, or willful ignorance. Atheists in the practical sense were those who behaved as though God, morals, ethics and social responsibility did not exist.

On the other hand, speculative atheism, which involves philosophical contemplation of the nonexistence of god(s), was often denied by theists throughout history. That anyone might reason their way to atheism was thought to be impossible. Thus, speculative atheism was collapsed into a form of practical atheism, or conceptualized as a hateful fight against God. These negative connotations are one of the reasons for the (continued) popularity of euphemistic alternative terms for atheists, like secularist, empiricist, and agnostic. These connotations likely arise from attempts at suppression and from historical associations with practical atheism. Indeed, the term godless is still used as an abusive epithet. Thinkers such as J. C. A. Gaskin have abandoned the term atheism in favor of unbelief, citing the fact that both the derogatory associations of the term and its vagueness in the public eye have rendered atheism an undesirable label. Despite these considerations, for others atheist has always been the preferred title, and several types of atheism have been identified by writers.

Weak and strong atheism

Some writers distinguish between weak and strong atheism. “Weak atheism,” sometimes called “soft atheism,” “negative atheism” or “neutral atheism,” is the absence of belief in the existence of deities without the positive assertion that deities do not exist. In this sense, weak atheism may be considered a form of agnosticism. These atheists may have no opinion regarding the existence of deities, either because of a lack of interest in the matter (a viewpoint referred to as apatheism), or a belief that the arguments and evidence provided by both theists and strong atheists are equally unpersuasive. Specifically, they argue that theism and strong atheism are equally untenable, on the grounds that asserting or denying the existence of deities requires a faith-claim.

On the other hand, “strong atheism,” also known as “hard atheism” or “positive atheism,” is the positive assertion that no deities exist. Many strong atheists have the additional view that positive statements of nonexistence are merited when evidence or arguments indicate that a deity's nonexistence is certain or probable. Strong atheism may be based on arguments that the concept of a deity is self-contradictory and therefore impossible (positive ignosticism), or that one or more attributes of a deity are incompatible with worldly realities.

Implicit and explicit atheism

The terms implicit and explicit atheism were coined by George H. Smith in 1979 for purposes of understanding atheism more narrowly. Implicit atheism is defined by Smith as the lack of theistic belief without conscious rejection of it. Explicit atheism, meanwhile, is defined by a conscious rejection of theistic belief and is sometimes called "antitheism."

As it happens, Smith's definition of explicit atheism is also the most common among laypeople. For laypersons, atheism is defined in the strongest possible terms, as the belief that there is no god. Thus, most laypeople would not recognize mere absence of belief in deities (implicit atheism) as a type of atheism at all, and would tend to use other terms, such as skepticism or agnosticism. Such usage is not exclusive to laypeople, however, as many atheist philosophers, including Theodore Drange, use the narrow definition.

Antitheism

Antitheism typically refers to a direct opposition to theism. In this sense, it is a form of critical strong atheism. While in other senses atheism merely denies the existence of deities, antitheists may go so far as to believe that theism is actually harmful for human beings. As well, they may simply be atheists who have little tolerance for theistic views, which they perceive to be irrational/dangerous. However, antitheism is also sometimes used, particularly in religious contexts, to refer to opposition to God or divine things, rather than an opposition to the belief in God. Using the latter definition, it is possible to be an antitheist without being an atheist or nontheist.

Atheism in philosophical naturalism

Despite the fact that many, if not most, atheists have preferred to claim that atheism is a lack of a belief rather than a belief in its own right, some atheist writers identify atheism with the naturalistic world view and defend it on that basis. The case for naturalism is used as a positive argument for atheism. For example, James Thrower proposes a "naturalistic" interpretation of events in the world, which takes nature as the paramount explanatory cause. As this worldview does not assert belief in any god beyond nature, it is therefore atheistic. Similarly, Julian Baggini argues that atheism must be understood not as a denial of religion, but instead as an affirmation of and commitment to the one world of nature. For Baggini, all unnatural (and supernatural) causes must be dismissed: "God is just one of the things that atheists don't believe in, it just happens to be the thing that, for historical reasons, gave them their name.[1] This variation of atheism, then, denies not only god(s) but also the existence of souls and other supernatural entities.

Atheism and philosophy

Atheism has been historically used in two senses.

1. Atheism has been a label given to a broad range of perspectives including pantheism and agnosticism, primarily by monotheists or religious authorities. These perspectives did not necessarily deny mystical or spiritual aspects of the world or of certain deities. The term “atheism” in this sense was coined in the sixteenth century to criticize positions that did not comply with the authorized views of the Christian church. The term is now extended to a wide variety of views whose contexts are quite different.

For example, Baruch Spinoza was denounced and labeled as an “atheist” by both Jewish and Christian authorities for over a century and Johann Gottlieb Fichte was expelled from university for the charge of “atheism.” Even Immanuel Kant, a Christian thinker, was accused as being “atheistic.”

2. Materialism. This position denies the reality or existence of any deity, being transcendent or immanent. It should be sharply distinguished from pantheism, agnosticism, and religious naturalism. Materialist atheism has an explicit ontological commitment for the denial of the reality of spiritual or divine being in any form.

Those who held this position include eighteenth-century French materialists such as Julien Offray de La Mettrie, Baron d’Holbach, and Denis Diderot and their ideological successors in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries such as Ludwig Feuerbach, Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Vladimir Lenin, Josef Stalin, and Mao Zedong.

During the Age of Enlightenment, atheism became the philosophical position of a growing minority, headed by the openly atheistic works of d'Holbach. In the nineteenth century, atheism became a powerful political tool through the writings of Feuerbach, who claimed God was a fictional projection fabricated by man. This idea greatly influenced Marx, the founder of communism, who believed that laborers turn to religion in order to dull the pain caused by the reality of social situations. Other atheists of the period included Friedrich Nietzsche, Jean-Paul Sartre and Sigmund Freud. The overall popularity of atheism in the nineteenth century led Nietzsche to coin the aphorism "God is dead." By the twentieth century, along with the spread of rationalism and secular humanism, atheism had become more widespread, particularly among scientists.

Materialistic atheism challenges any position, policy, institution, and movement that is based upon the assumption of the existence of a deity and spiritual dimension. The most radical and socially affective form of materialistic atheism in contemporary society is Marxism and its extensions. Furthermore, those materialistic atheists who actively seek to undermine existing religions are sometimes labeled as militant atheists. During the period of communist ascendancy, militant atheism enjoyed the full apparatus of the state, making it possible to attack religion and believers by every means imaginable with impunity. This included political, social, and military attacks on believers, and suppression of religion.

Atheism and World Religions

Ancient Greek and Roman

The oldest known variation of Western-style, philosophical atheism is attributed to the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus around 300 B.C.E. The goal of the Epicureans was mainly to alleviate fear of divine wrath by portraying it as irrational. One of the most eloquent expressions of Epicurean thought is found in Lucretius' On the Nature of Things (first century B.C.E.). He denied the existence of an afterlife and thought that if gods existed they were uninterested in human existence. For these reasons, they may be better described as materialists than atheists. Epicureans were not persecuted, but their teachings were controversial, and were harshly attacked by the mainstream schools of Stoicism and Neoplatonism.

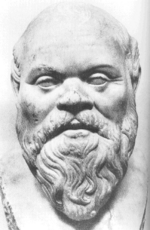

Many other Greek philosophers critiqued the then-prevalent henotheistic beliefs. Xenophanes, for instance, claimed that anthropomorphic and often immoral portrayals of the many gods were merely projections of humanity upon the divine. Ionic naturalists provided (pre-scientific) explanations for phenomena that had been previously been attributed to the gods. Democritus put forth the thesis that all phenomena in the world were merely transformations of eternal atoms, rather than anthropomorphic divinities. The Sophists criticized the various gods as products of human society and imagination. Critias, a famed dramatist and contemporary of Socrates, had one of his characters put forth the view that gods existed merely to bolster and reify societal codes of morality. Atheist thought culminated in the Greek tradition with Theodoret of Cyrrhus, who was the first to explicitly deny all forms of theism and the existence of any type of god.

Politically speaking, these developments were problematic, as theism was the fundamental belief that supported the divine right of the State in both Greece and Rome. As such, any person who did not believe in the deities supported by the State was fair game to accusations of atheism, a capital crime. For political reasons, Socrates in Athens (399 B.C.E.) was accused of being atheos (or "refusing to acknowledge the gods recognized by the state"). Early Christians in Rome were also considered subversive to the state religion and were thereby prosecuted as atheists. As such, it can be seen that charges of atheism (referring to the subversion of religion) were often used as a political mechanism by which to eliminate dissent.

Judaism

Belief in god is an indispensable requirement of the Jewish faith. This is evidenced by Judaism's paramount prayer, the Shema Israel, which asserts the monotheistic nature of god. Nonetheless, some strains of atheism have still originated from within the Judaic faith. For example, Richard Rubinstein, a Conservative rabbi who spent three years of his youth imprisoned at Auschwitz, put forward the claim that God died at that very concentration camp. God's failure to save the Jews, according to Rubinstein, marked a severance in the covenant between God and the Jewish people. Hence, the Jews were to face the universe alone as atheists; however, Rubenstein implored the Jewish people to retain their identity by continuing to follow moral imperatives laid out by God before his demise. Due to the extremely pessimistic tone of this notion, and the theological difficulties that arise with the claim that God can somehow cease to exist, Rubinstein's atheism was largely rejected.

In many modern movements in Judaism, rabbis have generally considered the behavior of a Jew to be the determining factor in whether or not one is considered an adherent of Judaism. Within these movements it is sometimes acknowledged that it is possible for a Jew to strictly practice Judaism as a faith, while at the same time being an agnostic or atheist. Some Jewish atheists reject Judaism altogether, but wish to continue identifying themselves with the Jewish people and culture. Jewish atheists who practice Humanistic Judaism embrace Jewish culture and history as the sources of their Jewish identity, rather than belief in a supernatural god.

Likewise, Jewish Reconstructionism is not dogmatic in many of its articles of faith, including belief in a deity, which is not required. As such, many Reconstructionist Jews adhere to deism, or else reject theism altogether and do not believe in any God. Sentiments toward atheist Jews are sometimes even quite positive. Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, first chief rabbi of the Jewish community in pre-state Israel, held that atheists do not actually deny God, but rather help toward a fuller realization of god. That is, atheists deny one of humanity's many images of God. Since any man-made image of God can be considered an idol, Kook held that, in practice, one could consider atheists as helping true religion eschew false images of God, in the end serving the purpose of true monotheism.

Christianity

Christianity, as a theistic and proselytizing religion, views atheism as sinful. According to Psalm 14:1, "The fool hath said in his heart, there is no God." Additionally, according to John 3:18-19, "He that believeth in him is not condemned: but he that believeth not is condemned already, because he hath not believed in the name of the only begotten Son of God. And this is the condemnation, that light is come into the world, and men loved darkness rather than light, because their deeds were evil." These passages suggest that those who reject the divinity of Jesus do so because of a proclivity to do evil, rather than evil being a consequence of their disbelief.

Islam

In Islam, atheists are categorized as kafir (كافر). This term translates roughly to "denier" or "concealer" and is also used to describe polytheists. In Islam, denial of god in such a way is one of the paramount transgressions, and as such, the noun kafir carries connotations of blasphemy and utter disconnection from the Islamic community. In Arabic, "atheism" is generally translated ilhad (إلحاد), which also means "heresy." The Qur'an is silent on the punishment for apostasy, though not on the subject itself. The Qur'an speaks repeatedly of people going back to unbelief after believing, but does not say that they should be killed or punished. Nonetheless, atheists have been subjected to such punishments throughout history in Islamic countries. Hence, atheists in such places frequently conceal their non-belief.

Hinduism

Several explicitly atheist schools emerged out of the writings of the Vedas, the texts that contain the core teachings of Hinduism. Of the six orthodox (astika) schools, Samkhya and Mimamsa, can be characterized as atheistic. Unlike other astika schools, Samkhya lacks the notion of a “higher being” that is the ground of all existence. Instead, Samkhya proposes a thoroughly dualistic understanding of the cosmos, in which two coexisting realities form the basis of reality: Purusha, the spiritual and Prakriti, the physical. The aim of life is the attainment of liberating self-knowledge through the separation of Purusha (spirit) from Prakriti (matter). Here, no God is present, yet Ultimate Reality in the form of the Purusha does exist. Therefore, Samkhya can be said to be a variety of Hinduism which falls into the classification of theistic atheism.

The Mimamsa schools focused their primary inquiry more upon the nature of dharma than the properties of a supreme deity. In doing so, they rejected theistic conceptions of the cosmos more outwardly than did the Samkhya. These rejections were developed in response to the theistic arguments being developed by the Nyaya and Vaisesika schools. The Purva Mimamsa school attacked their lines of reasoning vehemently, asserting no such god existed. Though Uttara Mimamsa (a sister school) was less forceful in its rejection of personal theism, it still viewed the concept of God as being ultimately illusory.

As well, Carvaka (also Charvaka) was an explicitly atheist school of Indian philosophy. It was not a religious tradition but rather a materialist school of thought, which rejected all sources of knowledge other than the senses. For the Charvakan, only the physical world exists, and therefore the only purpose of life is to live long and enjoy physical pleasures. There is no afterlife, no soul, and no God to them.

Jainism

Another heterodox school of Indian thought that is explicitly atheistic is Jainism. However, unlike the Carvakas, Jains acknowledge a spiritual realm beyond the physical, believing that the soul (jiva) is caught in an endless cycle of rebirth, and limited from its potential for eternal bliss by the material world. Jains follow a rigorous path of asceticism in order to release the soul from this cycle. The Jain cosmos is eternal, having no beginning and no end, which they believe obviates the necessity of having a creator. Additionally, Jain teachings provide a plethora of other arguments as to why there is no need for the conception of a god. These include many parallels with arguments for atheism from other traditions, including questions of divine mutability, perfection and accountability (theodicy). Hence, Jain philosophy denies all theistic sentiment.

While Jains have to some extent venerated Mahavira (the last prophet (Tirthankara) who achieved kevala—enlightenment or absolute knowledge—and systematized the Jain doctrine) throughout history (and still do at present), their gratitude toward him can hardly be considered the worship of a god.

Buddhism

While some schools of Buddhism—such as Theravada—are called atheistic, this label is misleading because Buddhism does believe in God but does not see them as eternal or creative forces in the origin of the universe. It also sees such gods as stuck in the wheel of samsara (rebirth and suffering). In the Pali Canon, earliest of the Buddhist scriptures, the Buddha criticizes the concept of a changeless deity as highly incoherent. Vasubandhu and Yasomitra, later Buddhist writers, note that if god is the singular cause of all things in existence, then all things should logically have been created at once. Since the world is constantly spawning new forms, however, one cause could never be considered adequate for the totality of existence. Further, since all things are created out of a succession of dharmas in a process called pratitya-samutpada, without exception everything is dependent on something else in order to come into existence. This precludes the possibility of an original cause without cause, as was popular in Aristotelian conceptions of God. Like the Jains, Buddhists also question a creator god's motivation for rendering the world, noting that god must enjoy human suffering, having created a world replete with it.

However, all canonical Buddhist texts affirm the existence (as distinct from the authority) of a great number of spiritual beings, including the Vedic deities. From the point of view of Western theism, certain concepts found in the Mahayana school of Buddhism (e.g. the characterization of Amitabha Buddha and the Pure Land) may seem to share characteristics with Western concepts of God, despite the fact that Shakyamuni Buddha himself denied that he was a god or divine. Furthermore, both the Nikaya/Mahayana schools of Buddhism provide deep spiritual regard to bodhisattvas, highly enlightened beings who are dedicated to assisting all sentient beings in achieving Buddhahood. However, in all cases it is necessary to recall the tradition's dogmatic insistence on the fundamental impermanence of all things. As such, though Amitabha Buddha and various bodhisattvas may be venerated, they are never (doctrinally-speaking) seen as possessing eternal life.

Confucianism

Confucius viewed obedience to the will of Heaven (Tian) as tantamount to correctly following social and ritual prescriptions. Xunzi, a later Confucian, while hearkening back to the teachings of Confucius, developed the first genuinely atheistic system of thought in Confucianism. He claimed that heaven was little more than a designation for the natural processes of cosmos, whereby good is rewarded and evil punished. In this conceptualization of the universe, Xunzi denied the existence of supernatural beings and spirits, and claimed that religious acts have no effect, a view somewhat congruent with atheism. Neo-Confucian writings, such as those of Zhu Xi, are considerably vaguer as to whether their conception of the Great Ultimate is like a personal deity or not, and whether their metaphysical worlds are structured on impersonal forces (such as material force (qi) and principle (li) rather than on god-like entities.

Daoism

The Dao, literally translated as "way," represents for Daoists the normative ontological and ethical standard by which the entire universe is constructed. According to Laozi, author of the Dao De Jing, all things are emanations of the Dao, from which they originate and eventually return. The Dao, however, cannot be described in words and can never be fully comprehended, though it can be perceived ever so vaguely in the processes of nature. The atheistic bent of Daoism is even more pronounced in the writings of Zhuangzi, who stresses both the futility of metaphysical speculation and the (likely) finality of death.

Since the Dao is so impersonal and incomprehensible, and is therefore in marked contrast to theistic belief systems, Daoists could be considered atheistic. Some scholars have claimed otherwise, accepting the concept of the Dao as sufficiently parallel with “god” in the Western understanding. Although the Western translation of the Dao as “god” in some editions of the Dao De Jing has been described as highly misleading, it is still a matter of debate whether the actual descriptions of the Dao have theistic or atheistic undertones.

Other Forms

Although atheistic beliefs are often accompanied by a total lack of spiritual beliefs, this is not an essential aspect, or even a necessary consequence, of atheism, as is evident in the aforementioned religious traditions. In addition, there are many modern movements which do not believe in God, yet cannot be classified as irreligious or secular. The Thomasine Church, for example, teaches that rational illumination (or gnosis) is the ultimate goal of their sacraments and meditations, as opposed to relating to a conception of God. Hence, the church does not require belief in theism. The Fellowship of Reason is an organization based in Atlanta, Georgia, which does not believe in God or other supernatural entities, but nonetheless affirms that churches and other religious organizations function to provide a moral community for their followers. There is also an atheist presence in Unitarian Universalism, an extremely liberal and inclusivist religion which accepts Buddhist, Christian, pantheist and even atheist creeds into its fold, among others.

Criticisms of atheism

Throughout human history, atheists and atheism have received much criticism, opposition, and persecution, chiefly from theistic sources. These have ranged from mere philosophical contempt to full-fledged persecution, as seen in medieval polemical literature and in Hitler's murderous vendetta against them. The most direct arguments against atheism are those in favor of the existence of deities, which would imply that atheism is simply untrue (for examples of these types of argument, see ontological argument, teleological argument and cosmological argument). However, more pointed criticisms exist. Both theists and weak atheists alike criticize the assertiveness of strong atheism, questioning whether or not one can assert the positive knowledge that something does not exist. While the strong atheist can make the claim that no evidence has been found for the existence of God, they cannot prove God does not exist. Atheists who make such statements have often been accused of dogmatism. Ultimately, these critics believe that atheism, if it is to remain philosophically coherent, should keep an open mind that evidence confirming a transcendent deity could appear in the future, rather than writing off the possibility entirely.

Another line of criticism has frequently associated atheism with immorality and evil, often characterizing it as a willful and malicious repudiation of divinity. This trend, as discussed above, has a long history and is likely tied to the once-undeniable role of religion as sole source of moral instruction. The modern secularization of the world and the growing acceptance of the sciences are currently diminishing the validity of this particular critique.

Regardless of the attempts made by atheists to defend their philosophical stance and alleviate negative misunderstandings of their beliefs, atheism is still viewed rather negatively by the general public. A 2006 study by researchers at the University of Minnesota involving a poll of two thousand households in the United States found atheists to be the most distrusted of minorities. Many of these respondents associated atheism with immorality, including criminal behavior, extreme materialism, and elitism.

See also

- agnosticism

- deism

- humanism

- nihilism

- objectivism

- panentheism

- pantheism

- rationalism

- secular humanism

- secularism

- theism

Footnotes

- ↑ Julian Baggini, Atheism: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003, ISBN 0192804243), 17.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ayer, A. J. “What I Believe.” Humanist 81(8) (1966): 226-228.

- Baggini, Julian. Atheism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0192804243

- Berman, David. A History of Atheism in Britain: from Hobbes to Russell. London: Routledge, 1990. ISBN 0415047277

- Berman, David. “David Hume and the Suppression of Atheism.” Journal of the History of Philosophy 21(3) (1983): 375-387.

- Borne, Étienne. Atheism. New York, NY: Hawthorn Books, 1961.

- Buckley, M. J. At the Origins of Modern Atheism. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0300048971

- Cudworth, Ralph. The True Intellectual System of the Universe: The First Part, Wherein all the Reason and Philosophy of Atheism is Confuted and its Impossibility Demonstrated. Reprint edition. Nabu Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1143641428

- d'Holbach, P. H. T. 1772. Good Sense. Electronic Text at Project Gutenberg. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- d'Holbach, P. H. T. (1770). The System of Nature. Available online from Project Gutenberg:

- de Mornay, Phillipe. A woorke concerning the Trewnesse of the Christian Religion, written in French; Against Atheists, Epicures, Paynims, Iewes, Mahumetists. London, 1587.

- Drachmann, A. B. Atheism in Pagan Antiquity. Chicago, IL: Ares Publishers, 1977 (original 1922). ISBN 0890052018

- Everitt, Nicholas. The Non-existence of God: An Introduction. London: Routledge, 2004. ISBN 0415301076

- Flew, Antony. God and Philosophy. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2005. ISBN 978-1591023302

- Flew, Antony. God, Freedom, and Immortality: A Critical Analysis. Amherst, NY: Prometheus, 1984. ISBN 0879751274

- Flew, Antony. “The Presumption of Atheism,” in God Freedom and Immorality: A Critical Analysis. Amherst, NY: Prometheus, 1984.

- Available online from Positive Atheism. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- Flint, Robert. Anti-Theistic Theories: Being the Baird Lecture for 1877, 5th ed. London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1894.

- Gaskin, J. C. A. (ed.). Varieties of Unbelief: from Epicurus to Sartre. New York, NY: Macmillan, 1989. ISBN 002340681X

- Harbour, Daniel. An Intelligent Person's Guide to Atheism. London: Duckworth, 2001. ISBN 0715632299

- James, George Alfred. "Atheism." Encyclopedia of Religion. Edited by Mercia Eliade. New York, NY: MacMillan Publishing, 1987.

- Krueger, D. E. What is Atheism?: A Short Introduction. Amherst, NY: Prometheus, 1998. ISBN 1573922145

- Le Poidevin, R. Arguing for Atheism: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion. London: Routledge, 1996. ISBN 0415093384

- Levin, S. Jewish Atheism. New Humanist 110(2) (1995): 13-15.

- Lovgren, Stefan. “Evolution and Religion Can Coexist, Scientists Say.” National Geographic (October 18, 2004). Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- Lyas, Colin. “On the Coherence of Christian Atheism.” Philosophy: the Journal of the Royal Institute of Philosophy 45(171) (1970): 1-19.

- Mackie, J. L. The Miracle of Theism: Arguments for and Against the Existence of God. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982. ISBN 019824682X

- Maritain, Jacques. The Range of Reason. London: Geoffrey Bles, 1953. Available online from The Jacques Maritain Center, University of Notre Dame. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- Martin, Michael. Atheism: A Philosophical Justification. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1990. ISBN 0877229430

- Martin, Michael, and R. Monnier (eds.). The Impossibility of God. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2003. ISBN 1591021200

- McGrath, A. The Twilight of Atheism: The Rise and Fall of Disbelief in the Modern World. Toronto: Doubleday, 2004. ISBN 0385500629

- Mills, D. Atheist Universe. Xlibris, 2004. ISBN 1413434819

- Nagel, Ernest. “A Defence of Atheism,” in A Modern Introduction to Philosophy: Readings from Classical and Contemporary Sources, edited by Paul Edwards and Arthur Pap, 460-472. New York, NY: Free Press, 1965.

- Nielsen, Kai. Philosophy and Atheism. Amherst, NY: Prometheus, 1985. ISBN 0879752890

- Reid, J. P. “Atheism,” in New Catholic Encyclopedia, 1000-1003. New York, NY McGraw-Hill, 1967.

- Robinson, Richard. An Atheist's Values. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing, 1975. ISBN 978-0631159704

- Sharpe, R.A. The Moral Case Against Religious Belief. London: SCM Press, 1997. ISBN 0334026806

- Smith, George H. Atheism, Ayn Rand, and Other Heresies. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 1990. ISBN 978-0879755775

- Excerpt: “Defining Atheism” at Positive Atheism.

- Smith, George H. Atheism: The Case Against God. Amherst, NY: Prometheus, 1979. ISBN 087975124X

- Excerpt: “The Scope of Atheism” at Positive Atheism. Retrieved September 5, 2007.

- Sobel, Jordan H. Logic and Theism: Arguments For and Against Beliefs in God. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. ISBN 0521826071

- Stein, G. (ed.). The Encyclopaedia of Unbelief. 2 vols. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 1984. ISBN 0879753072

- "Systems of Religious and Spiritual Belief." The New Encyclopedia Britannica. Vol. 26, 530-577. Chicago, IL: Encyclopedia Britannica Inc., 2002.

- Thrower, James. A Short History of Western Atheism. London: Pemberton, 1971. ISBN 0301711011

- Vitz, Paul. Faith of the Fatherless: The Psychology of Atheism. Dallas, TX: Spence, 1999. ISBN 1890626120

External links

All links retrieved August 19, 2023.

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Paideia Project Online

- Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.