Lake

A lake (from the Latin word lacus) is an inland body of water, not part of the ocean, that is larger and deeper than a pond and is localized at the bottom of a basin.[1] There is, however, a lack of consensus on definitions used to distinguish between lakes and ponds. Some have defined a lake as a water body with a minimum surface area of 2 hectares (5 acres, 20,000 square meters), others have put the figure at 8 hectares (20 acres, 80,000 square meters). In ecology, the environment of a lake is described as lacustrine. The study of lakes, ponds, and other inland bodies of water and related ecosystems is called limnology.

A lake may receive water from one or more of the following sources: melting ice, streams, rivers, aquifers, and direct rainfall or snowfall. If the rate of replenishment is too low, the lake may lose water by evaporation or underground seepage or both.

A lake sustains a variety of living organisms and thus forms its own ecosystem. In addition, it moderates the area's temperature and climate by regulating wind temperature. If fed by a stream, it regulates the flow of the stream. For humans, a lake is usually valuable as a source of freshwater that may then be used for drinking and irrigating fields. It may also be used for recreational activities. Some saltwater lakes are useful for the minerals they contain. Some lakes have been artificially constructed or modified for hydroelectric power generation and industrial use.

Terminology

The term "lake" is occasionally used to describe a feature such as Lake Eyre, which is a dry basin most of the time but may become filled under seasonal conditions of heavy rainfall. In addition, a pool of molten lava may be called a "lava lake." Large lakes are occasionally referred to as "inland seas," and small seas are occasionally called lakes.

There is considerable uncertainty about definitions that distinguish between lakes and ponds. For example, limnologists have defined lakes as water bodies that are simply larger versions of ponds, or that have wave action on the shoreline, or where wind-induced turbulence plays a major role in mixing the water column. None of these definitions completely excludes ponds, and all are difficult to measure. Furthermore, in common usage, many lakes bear names ending with the word "pond," and a lesser number of bodies of water known as "lakes" could be better described (in quasi-technical terms) as ponds. In short, there is no current internationally accepted definition of either term across scientific disciplines or political boundaries. Within disciplines, authors are careful to define environmental geographic circumstances.

In light of these uncertainties, simple, size-based definitions are increasingly used to distinguish between ponds and lakes. In the United Kingdom, for example, the charity Pond Conservation has defined lakes as water bodies of 2 hectares (5 acres) or more in surface area.[2] Elsewhere, other researchers have treated lakes as water bodies of 5 hectares (12 acres) and above, or 8 hectares (20 acres) and above. Charles Elton, one of the founders of ecology, regarded lakes as water bodies of 40 hectares (99 acres) or more, a value larger than what most modern researchers consider appropriate.[3]

In naming lakes (at least in North America), the word "lake" is often placed after the name of a smaller lake, as in Green Lake (Seattle), but the word order is often inverted when naming larger lakes, as in Lake Ontario. In some places, the word "lake" does not correctly appear in the name at all (such as Windermere in Cumbria).

In the English Lake District, only one lake (Bassenthwaite Lake) is actually called a lake; the others are called "meres" or "waters." Only six bodies of water in Scotland are known as lakes (the others are lochs): the Lake of Menteith, the Lake of the Hirsel, Pressmennan Lake, Cally Lake near Gatehouse of Fleet, the saltwater Manxman's Lake at Kirkcudbright Bay, and The Lake at Fochabers. Of these only the Lake of Menteith and Cally Lake are natural bodies of freshwater.

Distribution of lakes

The vast majority of lakes on Earth are freshwater, and most lie in the Northern Hemisphere at higher latitudes. More than 60 percent of the world's lakes are in Canada, as a result of the deranged drainage system that dominates the country. Many lakes occupy the basins and valleys created by glaciers in past epochs.

Finland, known as The Land of the Thousand Lakes, has 187,888 lakes, of which 60,000 are large.[4] The U.S. state of Minnesota is referred to as The Land of Ten Thousand Lakes,, and issues automobile license plates boasting of its "10,000 lakes." The license plates of the Canadian province of Manitoba used to claim "100,000 lakes," as one-upmanship on Minnesota.

Globally, lakes are greatly outnumbered by ponds. Of an estimated 304 million standing water bodies worldwide, 91 percent are 1 hectare (2.5 acres) or less in area.[5] Also, small lakes are much more numerous than big ones. However, large lakes contribute disproportionately to the area of standing water with 122 large lakes of 1,000 square kilometers (390 sq mi, 100,000 ha, 247,000 acres) or more representing about 29 percent of the total global area of standing inland water.

Origins of natural lakes

A lake may be formed by any of a number of natural processes. For example, a recent tectonic uplift of a mountain range can create bowl-shaped depressions that accumulate water and form lakes. Alternatively, the advance and retreat of glaciers can scrape depressions in the surface where water accumulates. Such lakes are common in Scandinavia, Patagonia, Siberia, and Canada. Among the most notable examples are the Great Lakes of North America.

Lakes can also be formed by landslides or glacial blockages. An example of the latter occurred during the last ice age in the U.S. state of Washington, when a huge lake formed behind a glacial flow. When the ice retreated, the result was an immense flood that created the Dry Falls at Sun Lakes, Washington.

Salt lakes (also called saline lakes) can form where there is no natural outlet, or where the water evaporates rapidly and the drainage surface of the water table has a higher-than-normal salt content. Examples of salt lakes include Great Salt Lake, the Caspian Sea, the Aral Sea, and the Dead Sea. Some lakes, such as Lake Jackson in Florida, came into existence as a result of sinkhole activity.

Small, crescent-shaped lakes, called oxbow lakes, may form in river valleys as a result of meandering. The slow-moving river forms a sinuous shape as the outer side of bends are eroded away more rapidly than the inner side. Eventually a horseshoe bend is formed and the river cuts through the narrow neck. This new passage then forms the main passage for the river and the ends of the bend become silted up, thus forming a bow-shaped lake.

Crater lakes are formed in volcanic calderas which fill up with precipitation more rapidly than they empty via evaporation. An example is Crater Lake in Oregon, located within the caldera of Mount Mazama. The caldera was created in a massive volcanic eruption that led to the subsidence of Mount Mazama around 4860 B.C.E.

Lake Vostok is a subglacial lake in Antarctica, possibly the largest in the world. Based on the pressure from the ice atop it and its internal chemical composition, one may predict that drilling the ice into the lake would produce a geyser-like spray.

Most lakes are geologically young and shrinking, since the natural results of erosion will tend to wear away the sides and fill the basin. Exceptions are lakes such as Lake Baikal and Lake Tanganyika that lie along continental rift zones and were created by the crust's subsidence as two plates were pulled apart. These lakes are the oldest and deepest in the world. Lake Baikal, which is 25-30 million years old, is deepening at a faster rate than it is being filled by erosion and may be destined over millions of years to become attached to the global ocean. The Red Sea, for example, is thought to have originated as a rift valley lake.

Types of lakes

Lakes may be classified according to their manner of formation or current characteristics. Various types of lakes are noted below.

- Artificial lake: Many lakes are artificial. They may be constructed for various purposes, such as hydroelectric power generation, recreation, industrial use, agricultural use, or domestic water supply. An artificial lake may be created in different ways: by flooding land behind a dam (called an impoundment or reservoir); by deliberate human excavation; or by the flooding of an excavation incident to a mineral-extraction operation (such as an open pit mine or quarry). Some of the world's largest lakes are reservoirs.

- Crater lake: A lake that is formed in a volcanic caldera or crater after the volcano has been inactive for some time. Water in this type of lake may be fresh or highly acidic and may contain various dissolved minerals. Some crater lakes also have geothermal activity, especially if the volcano is merely dormant rather than extinct.

- Endorheic lake (also called terminal or closed): A lake that has no significant outflow, either through rivers or underground diffusion. Any water in an endorheic basin leaves the system only through evaporation or seepage. This type of lake, exemplified by Lake Eyre in central Australia and the Aral Sea in central Asia, is most common in desert locations.

- Eolic lake: A lake that has formed in a depression created by the activity of the winds.

- Fjord lake: A lake in a glacially eroded valley that has been eroded below sea level.

- Former lake: A lake that is no longer in existence. This category includes prehistoric lakes and those that have permanently dried up through evaporation or human intervention. Owens Lake in California, USA, is an example of a former lake. Former lakes are a common feature of the Basin and Range area of southwestern North America.

- Glacial lake: It is a lake that was formed from a melted glacier.

- Lava lake: This term refers to a pool of molten lava in a volcanic crater or other depression. The term lava lake may also be used after the lava has partly or completely solidified.

- Meromictic lake: A lake containing layers of water that do not intermix. The deepest layer of water in such a lake does not contain any dissolved oxygen. The layers of sediment at the bottom of a meromictic lake remain relatively undisturbed because there are no living organisms to stir them up.

- Oxbow lake: This type of lake, characterized by a distinctive curved shape, is formed when a wide meander from a stream or a river is cut off.

- Periglacial lake: Part of the lake's margin was formed by an ice sheet, ice cap, or glacier, the ice having obstructed the natural drainage of the land.

- Rift lake: A lake that is formed as a result of subsidence along a geological fault in the Earth's tectonic plates. Examples include the Rift Valley lakes of eastern Africa and Lake Baikal in Siberia.

- Seasonal lake: A lake that exists as a body of water during only part of the year.

- Shrunken lake: Closely related to former lakes, a shrunken lake is one that has drastically decreased in size over geological time. Lake Agassiz, which once covered much of central North America, is a good example of a shrunken lake. Two notable remnants of this lake are Lake Winnipeg and Lake Winnipegosis.

- Subglacial lake: A lake that is permanently covered by ice. Such lakes can occur under glaciers, ice caps, or ice sheets. There are many such lakes, but Lake Vostok in Antarctica is by far the largest. They are kept liquid because the overlying ice acts as a thermal insulator, retaining energy introduced to its underside in any of several ways: by friction, water percolating through crevasses, pressure from the mass of the ice sheet above, or geothermal heating below.

- Underground lake: A lake that is formed beneath the surface of the Earth's crust. Such a lake may be associated with caves, aquifers, or springs.

There is also evidence of extraterrestrial lakes, although they may not contain water. For instance, NASA has announced "definitive evidence of lakes filled with methane" on Saturn's moon Titan, as recorded by the Cassini Probe.

Characteristics

Lakes have a variety of characteristics in addition to those mentioned above. Their features include a drainage basin (or catchment area), inflow and outflow, nutrient content, dissolved oxygen, pollutants, pH, and sediment accumulation.

Changes in the level of a lake are controlled by the difference between the input and output, compared to the total volume of the lake. Significant input sources are: precipitation onto the lake, runoff carried by streams and channels from the lake's catchment area, groundwater channels and aquifers, and artificial sources from outside the catchment area. Output sources are evaporation from the lake, surface and groundwater flows, and any extraction of lake water by humans. As climate conditions and human water requirements vary, these will create fluctuations in the lake level.

Lakes can be also categorized on the basis of their richness in nutrients, which typically affects plant growth:

- Oligotrophic lakes are nutrient-poor and generally clear, having a low concentration of plant life.

- Mesotrophic lakes have good clarity and an average level of nutrients.

- Eutrophic lakes are enriched with nutrients (such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and organic substances), resulting in good plant growth and possible algal blooms.

- Hypertrophic lakes are bodies of water that have been excessively enriched with nutrients. These lakes typically have poor clarity and are subject to devastating algal blooms. Lakes typically reach this condition after heavy use of fertilizers in the lake catchment area. Such lakes are of little use to humans and have a poor ecosystem due to decreased dissolved oxygen.

Due to the unusual relationship between the temperature and density of water, lakes form layers called thermoclines—layers of drastically varying temperature relative to depth. Freshwater is most dense at about 4 degrees Celsius (39.2 °F) at sea level. When the temperature of the water at the surface of a lake reaches the same temperature as deeper water, as it does during the cooler months in temperate climates, the water in the lake can mix, bringing oxygen-starved water up from the depths and bringing oxygen down to decomposing sediments. Deep, temperate lakes can maintain a reservoir of cold water year-round, which allows some cities to tap that reservoir for deep lake water cooling.

Given that the surface water of deep tropical lakes never reaches the temperature of maximum density, there is no process that makes the water mix. The deeper layer becomes oxygen starved and can become saturated with carbon dioxide, or other gases such as sulfur dioxide if there is even a trace of volcanic activity. Exceptional events, such as earthquakes or landslides, can cause mixing, which rapidly brings up the deep layers and may release a vast cloud of toxic gases that lay trapped in solution in the colder water at the bottom of the lake. This is called a limnic eruption. An example of such a release is the 1986 disaster at Lake Nyos in Cameroon. The amount of gas that can be dissolved in water is directly related to pressure. As the once-deep water rises, the pressure drops, and a vast amount of gas comes out of solution. Under these circumstances, even carbon dioxide is toxic because it is heavier than air and displaces it, so it may flow down a river valley to human settlements, causing mass asphyxiation.

The material at the bottom of a lake, or lake bed, may be composed of a wide variety of inorganics, such as silt or sand, and organic material, such as decaying plant or animal matter. The composition of the lake bed has a significant impact on the flora and fauna found within the lake's environs by contributing to the amounts and the types of nutrients available.

Limnology

Limnology is the study of inland bodies of water and related ecosystems. In this field of study, lakes are divided into three zones:

- the littoral zone, a sloped area close to land;

- the photic or open-water zone, where sunlight is abundant;

- the deep-water profundal or benthic zone, which receives little sunlight.

The depth to which light can penetrate a lake depends on turbidity of the water, which in turn is determined by the density and size of suspended particles. The particles can be sedimentary or biological in origin and are responsible for the color of the water. Decaying plant matter, for instance, may be responsible for a yellow or brown color, while algae may produce greenish water. In very shallow water bodies, iron oxides make the water reddish brown. Biological particles include algae and detritus. Bottom-dwelling detritivorous fish can be responsible for turbid waters, because they stir the mud in search of food. Piscivorous fish contribute to turbidity by eating plant-eating (planktonivorous) fish, thus increasing the amount of algae.

Light depth or transparency is measured by using a Secchi disk, a 20-centimeter (8-inch) disk with alternating white and black quadrants. The depth at which the disk is no longer visible is the Secchi depth, a measure of transparency. The Secchi disk is commonly used to test for eutrophication.

A lake moderates the surrounding region's temperature and climate because water has a very high specific heat capacity (4,186 J•kg−1•K−1). In the daytime, a lake can cool the land beside it with local winds, resulting in a sea breeze; in the night, it can warm it with a land breeze.

How Lakes Disappear

On geologic time scales, lakes—including those created by man-made concrete edifices—are temporary bodies, as ongoing geologic forces will eventually either break the earth and rock dams that hold them, or fill the basin with sediments forming a fresh geologic record.

A lake may be infilled with deposited sediment and gradually become a wetland such as a swamp or marsh. Large water plants, typically reeds, accelerate this closing process significantly because they partially decompose to form peat soils that fill the shallows. Conversely, peat soils in a marsh can naturally burn and reverse this process to recreate a shallow lake. Turbid lakes and lakes with many plant-eating fish tend to disappear more slowly.

A "disappearing" lake (barely noticeable on a human timescale) typically has extensive plant mats at the water's edge. These become a new habitat for other plants, like peat moss when conditions are right, and animals, many of which are very rare. Gradually the lake closes, and young peat may form, producing a fen. In lowland river valleys, where a river can meander, the presence of peat is explained by the infilling of historical oxbow lakes. In the very last stages of succession, trees may grow in, eventually turning the wetland into a forest.

Some lakes disappear seasonally. They are called intermittent lakes and are typically found in karstic terrain. A prime example of an intermittent lake is Lake Cerknica in Slovenia.

Sometimes a lake will disappear quickly. On 3 June, 2005, in Nizhny Novgorod Oblast, Russia, a lake called Lake Beloye vanished in a matter of minutes. News sources reported that government officials theorized that this strange phenomenon may have been caused by a shift in the soil underneath the lake that allowed its water to drain through channels leading to the Oka River.[6]

The presence of ground permafrost is important to the persistence of some lakes. According to research published in the journal Science ("Disappearing Arctic Lakes," June 2005), thawing permafrost may explain the shrinking or disappearance of hundreds of large Arctic lakes across western Siberia. The idea here is that rising air and soil temperatures thaw permafrost, allowing the lakes to drain away into the ground.

Neusiedler See, located in Austria and Hungary, has dried up many times over the millennia. As of 2005, it is again rapidly losing water, giving rise to the fear that it will be completely dry by 2010.

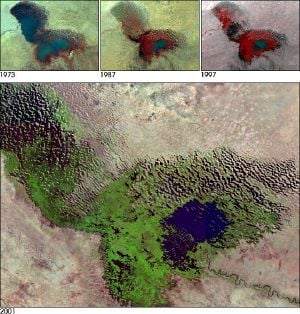

Some lakes disappear because of human development factors. The shrinking Aral Sea is described as being "murdered" by the diversion for irrigation of the rivers feeding it.

Extraterrestrial lakes

At present, the surface of the planet Mars is too cold and has too little atmospheric pressure to permit the pooling of liquid water on its surface. Geologic evidence appears to confirm, however, that ancient lakes once formed on the surface. It is also possible that volcanic activity on Mars will occasionally melt subsurface ice creating large lakes. Under current conditions, this water would quickly freeze and evaporate unless insulated in some manner, such as by a coating of volcanic ash.

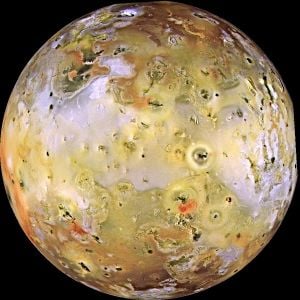

Jupiter's small moon Io is volcanically active due to tidal stresses, and as a result sulfur deposits have accumulated on the surface. Some photographs taken during the Galileo mission appear to show lakes of liquid sulfur on the surface.

Photographs taken by the Cassini-Huygens spacecraft on July 24, 2006, give strong evidence for the existence of methane or ethene lakes on Saturn's largest moon, Titan.

Dark basaltic plains on the Moon, similar to but smaller than lunar maria, are called lacus (Latin for "lake") because early astronomers thought they were lakes of water.

Notable lakes

- The largest lake in the world by surface area is the Caspian Sea. With a surface area of 394,299 km² (152,240 mi²), it has a surface area greater than the next six largest lakes combined.

- The deepest lake is Lake Baikal in Siberia, with a bottom at 1,637 m (5,371 ft). Its mean depth is also the highest in the world (749 m)

It is the world's largest freshwater lake by volume (23,000 km³), and the second longest (about 630 km from tip to tip). - The longest freshwater lake is Lake Tanganyika, with a length of about 660 km (measured along the lake's center line).

It is also the second deepest in the world (1,470 m) after lake Baikal. - The world's oldest lake is Lake Baikal, followed by Lake Tanganyika (Tanzania).

- The world's highest lake is an unnamed pool on Ojos del Salado on the border of Argentina and Chile at 6,390 meters (20,965 ft).[7] The Lhagba Pool in Tibet at 6,368 m (20,892 ft) comes second.[8]

- The world's highest commercially navigable lake is Lake Titicaca in Peru and Bolivia at 3,812 m (12,507 ft). It is also the largest freshwater (and second largest overall) lake in South America.

- The world's lowest lake is the Dead Sea, bordering Israel, Jordan at 418 m (1,371 ft) below sea level. It is also one of the lakes with highest salt concentration.

- Lake Superior is the largest freshwater lake by surface area (82,414 km²). It is also the third largest by water volume. However, Lake Huron and Lake Michigan form a single hydrological system with surface area 117,350 km², sometimes designated Lake Michigan-Huron. All these are part of the Great Lakes of North America.

- Lake Huron has the longest lake coastline in the world: about 2980 km, excluding the coastline of its many inner islands.

- The largest island in a freshwater lake is Manitoulin Island in Lake Huron, with a surface area of 2,766 km². Lake Manitou, located on Manitoulin Island, is the largest lake on an island in a freshwater lake.

- The largest lake located on an island is Nettilling Lake on Baffin Island.

- The largest lake in the world that drains naturally in two directions is Wollaston Lake.

- Lake Toba on the island of Sumatra is located in what is probably the largest resurgent caldera on Earth.

- The largest lake located completely within the boundaries of a single city is Lake Wanapitei in the city of Sudbury, Ontario, Canada.

Before the current city boundaries came into effect in 2001, this status was held by Lake Ramsey, also in Sudbury. - Lake Enriquillo in Dominican Republic is the only saltwater lake in the world inhabited by crocodiles.

- Lake of the Ozarks is one of the United States largest man made lakes, created by the Bagnell Dam [9]

Largest by continent

The largest lakes (in terms of surface area) are listed below, with their continental locations.

- Africa: Lake Victoria, the second largest freshwater lake on Earth. It is one of the Great Lakes of Africa.

- Antarctica: Lake Vostok (subglacial).

- Asia: Caspian Sea, the largest lake on Earth. However, the Europe-Asia border is conventionally drawn through it. The largest lake entirely in Asia is Lake Baikal.

- Australia: Lake Eyre.

- Europe: Lake Ladoga, followed by Lake Onega, both located in northwestern Russia.

- North America: Lake Michigan-Huron.

- South America: Lake Titicaca. It is the highest navigable body of water on Earth, located 3,821 m above sea level. Some consider Lake Maracaibo as the largest lake in South America, but it lies at sea level and has a relatively wide opening to the sea, so it is better described as a bay.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Lake. Dictionary.com. Retrieved August 9, 2008.

- ↑ P. Williams, M. Whitfield, J. Biggs, S. Bray, G. Fox, P. Nicolet and D. Sear. 2004. Comparative biodiversity of rivers, streams, ditches and ponds in an agricultural landscape in Southern England. Biological Conservation 115:329-341.

- ↑ C.S. Elton, and R.S. Miller. 1954. The ecological survey of animal communities: with a practical system of classifying habitats by structural characters. Journal of Ecology 42:460-496.

- ↑ Home Page. Statistics Finland. Retrieved August 9, 2008.

- ↑ J.A. Downing, Y.T. Prairie, J.J. Cole, C.M. Duarte, L.J. Tranvick, R.G. Striegel, W.H. McDowell, P. Kortelainen, J.M. Melack and J.J. Middleburg. 2006. The global abundance and size distribution of lakes, ponds and impoundments. Limnology and Oceanography 51:2388-2397.

- ↑ Kim Murphy, 2005. Lake's disappearing act stuns Russian town. The Montana Standard. Retrieved August 9, 2008.

- ↑ Andes Website - Information about Ojos del Salado volcano, a high mountain in South America and the World's highest volcano. Andes.org.

- ↑ Carl Drews, 2002. Highest Lake. HighestLake.com. Retrieved August 9, 2008.

- ↑ Home Page. LakeOzark.com. Retrieved August 9, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barnes, Julia. 2004. 101 Facts About Lakes. 101 Facts About Our World. Milwaukee, WI: Gareth Stevens Pub. ISBN 083683707X.

- Scheffer, Marten. 2004. Ecology of Shallow Lakes. Population and Community Biology Series. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 1402023065.

- Wetzel, Robert G. 2001. Limnology: Lake and River Ecosystems. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. ISBN 0127447601.

External links

All links retrieved October 21, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.