Lake Superior

| Lake Superior | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | |

| Primary sources | Nipigon River, St. Louis River Pigeon River Pic River White River Michipicoten River Kaministiquia River |

| Primary outflows | St. Marys River |

| Basin countries | Canada, USA |

| Max length | 563 km (350 mi) |

| Max width | 257 km (160 mi) |

| Surface area | 82,414 km² (31,820 mi²)[1] Canadian portion 28,700 km² (11,080 mi²) |

| Average depth | 147 m (482 ft) |

| Max depth | 406 m (1333 ft)[1] |

| Water volume | 12,100 km³ (2900 mi³) |

| Residence time (of lake water) | 191 years |

| Shore length1 | 4385 km (2725 mi) |

| Surface elevation | 183 m (600 ft)[1] |

| Islands | Isle Royale Apostle Islands |

| Settlements | Duluth, Minnesota Superior, Wisconsin Thunder Bay, Ontario Marquette, Michigan Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario |

| 1 Shore length is an imprecise measure which may not be standardized for this article. | |

Lake Superior, bounded by Ontario, Canada, and the U.S. state of Minnesota to the north, and the states of Wisconsin and Michigan to the south, is the largest of North America's Great Lakes. Receiving water from approximately 200 rivers, it is the largest freshwater lake in the world by surface area and is the world's third-largest freshwater lake by volume. Its shoreline is almost 2,800 miles long.

With an average depth approaching 500 feet, it is also is the coldest and deepest (1,332 feet at its deepest point) of the Great Lakes. Its drainage basin covers 49,300 square miles. Most of the basin is sparsely populated, and heavily forested, with little agriculture because of a cool climate and poor soils.

Name

In the Ojibwe language, the lake is called "Gichigami" (Shining Big-Sea-Water), but it is better known as "Gitche Gumee," as recorded by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in "The Song of Hiawatha." Lake Superior is referred to as "Gitche Gumee" in the song "The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald," by Gordon Lightfoot.

The lake was named le lac supérieur, or "Upper Lake," in the seventeenth century by French explorers because it was located above Lake Huron.

History

The first people came to the Lake Superior region 10,000 years ago after the retreat of the glaciers in the last Ice Age. They were known as the Plano, and they used stone-tipped spears to hunt caribou on the northwestern side of Lake Minong.

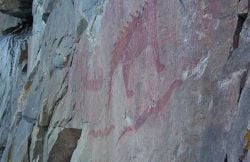

The next documented people were known as the Shield Archaic (c. 5000-500 B.C.E.). Evidence of this culture can be found at the eastern and western ends of the Canadian shore. They used bows and arrows and dugout canoes; fished, hunted, mined copper for tools and weapons, and established trading networks. They are believed to be the direct ancestors of the Ojibwe and Cree.[2]

The Laurel people (c. 500 B.C.E. to 500 C.E.) developed seine net fishing, according to evidence in rivers emptying into Superior such as the Pic and Michipicoten.

Another culture, known as the Terminal Woodland Indians (c. 900-1650 C.E.), has been found. They were Algonquan people who hunted, fished, and gathered berries. They used snow shoes, birch bark canoes, and conical or domed lodges. Nine layers of their encampments have been discovered at the mouth of the Michipicoten River. Most of the Pukaskwa Pits were likely made during this time.[2]

The Anishinabe, also known as the Ojibwe or Chippewa, have inhabited the Lake Superior region for over five hundred years, and were preceded by the Dakota, Fox, Menominee, Nipigon, Noquet, and Gros Ventres. They called Lake Superior Anishnaabe Chi Gaming, or "the Ojibwe's Ocean." After the arrival of Europeans, the Anishinabe made themselves the middle-men between the French fur traders and other Native peoples. They soon became the dominant Indian nation in the region: they forced out the Sioux and Fox and defeated the Iroquois west of Sault Ste. Marie in 1662. By the mid-1700s, the Ojibwe occupied all of Lake Superior's shores.[2]

In the 1700s, the fur trade in the region was booming, with the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) having a virtual monopoly. In 1783, however, the North West Company (NWC) was formed to compete with HBC. The NWC built forts on Lake Superior at Grand Portage, Nipigon, the Pic River, the Michipicoten River, and Sault Ste. Marie. But by 1821, with competition taking too great a toll on both, the companies merged under the Hudson's Bay Company name.

Many towns around the lake are either current or former mining areas, or engaged in processing or shipping. Today, tourism is another significant industry as the sparsely populated Lake Superior country, with its rugged shorelines and wilderness, attracts tourists and adventurers.

Geology

Lake Superior's North Shore dates back to the beginnings of the earth. About 2.7 billion years ago, magma forcing its way to the surface created the intrusive granite rock of the Canadian Shield. This rock sank into the mantle numerous times, finally rising and cooling to become the formations that can be seen on the North Shore today. It was in this period, the Kenora Orogeny, that many valuable metals were deposited. This is why the land surrounding the lake has proved to be rich in minerals. Copper, iron, silver, gold, and nickel are or were the most frequently mined. Examples include the Hemlo gold mine near Marathon, copper at Point Mamainse, silver at Silver Islet, and uranium at Theano Point.

The mountains steadily eroded starting about 2.49 billion years ago, depositing layers of sediment which compacted and became limestone, dolostone, taconite, and the shale at Kakabeka Falls.

About 1.1 billion years ago, the continent drifted apart, creating one of the deepest rifts in the world. The lake lies above this long-extinct Mesoproterozoic rift valley, the Midcontinent Rift, which explains its great depths. Magma was injected between layers of sedimentary rock, forming diabase sills, a hard rock which resists corrosion. This hard diabase protects the layers of sedimentary rock below, forming the flat-topped mesas in the Thunder Bay area.

Lava erupting from the rift cooled, forming the black basalt rock of Michipicoten Island, Black Bay Peninsula, and St. Ignace Island.

Around 1.6 million years ago, during the last Great Ice Age, ice covered the region at a thickness of 1.25 miles (2 km). The land contours familiar today were carved by the advance and retreat of the ice sheet. The retreat, 10,000 years ago, left gravel, sand, clay, and boulder deposits. Glacial meltwaters gathered in the Superior basin creating Lake Minong, a precursor to Lake Superior.[2] Without the immense weight of the ice, the land rebounded, and a drainage outlet formed at Sault Ste. Marie, which would become known as St. Mary's River.

Geography

The largest island in Lake Superior is Isle Royale, part of the U.S. state of Michigan, off the Upper Peninsula. Other large islands include Madeline Island in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and Michipicoten in the Canadian province of Ontario.

The larger towns on Lake Superior include: The twin ports of Duluth, Minnesota and Superior, Wisconsin; Thunder Bay, Ontario; Marquette, Michigan; and the two cities of Sault Ste. Marie, in Michigan and in Ontario. Duluth, at the western tip of Lake Superior, is the most inland point on the Saint Lawrence Seaway and the most inland port in the world.

Among the scenic areas on the lake are: The Apostle Islands National Lakeshore; Isle Royale National Park; Pukaskwa National Park; Lake Superior Provincial Park; Grand Island National Recreation Area; Sleeping Giant (Ontario); and Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore.

Hydrography

Lake Superior is the largest freshwater lake in the world by surface area. Lake Baikal in Russia is larger by volume, as is Lake Tanganyika. The Caspian Sea, while vastly larger than Lake Superior in both surface area and volume, is saline; presently isolated, in the past, it has been repeatedly connected to, and isolated from, the Mediterranean via the Black Sea.

Lake Superior (48°00’N, 88°00’W) has a surface area of 31,820 square miles (82,414 km²)[1]—which is larger than the U.S. state of South Carolina. It has a maximum length of 350 miles (563 km) and maximum width of 160 miles (257 km). Its average depth is 483 feet (147 m) with a maximum depth of 1,333 feet (406 m).[1] Lake Superior contains 2,900 cu mi (12,100 km³) of water. There is enough water in Lake Superior to cover the entire land mass of North and South America with a foot (30 cm) of water. The shoreline of the lake stretches 2,726 miles (4,385 km) (including islands). The lake's elevation is 600 feet (183 m)[1] above sea level. American limnologist J. Val Klump was the first person to reach the lowest depth of Lake Superior on July 30, 1985, as part of a scientific expedition.

Annual storms on Lake Superior regularly record wave heights of over 20 feet (6 m). Waves well over 30 feet (9 m) have been recorded.[2]

Water levels, including diversions of water from the Hudson Bay watershed, are governed by the International Lake Superior Board of Control which was established in 1914, by the International Joint Commission.

Tributaries and outlet

The lake is fed by over 200 rivers. The largest include the Nipigon River, the St. Louis River, the Pigeon River, the Pic River, the White River, the Michipicoten River, the Brule River, and the Kaministiquia River. Lake Superior drains into Lake Huron through the St. Marys River. The rapids on the river resulting from the 25 foot (7.6 m) difference in elevation between Lake Superior and Lake Huron necessitated the building of the Sault Locks (pronounced "soo"), a part of the Great Lakes Waterway, to move boats between the Lakes. The first locks were built in 1855, between the twin cities of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario and Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan. There are now five locks; the largest of which is the Poe Lock.[3]

Climate

Lake Superior's size creates a localized oceanic or maritime climate (more typically seen in locations like Nova Scotia). The water's slow reaction to changing temperatures helps to moderate surrounding air temperatures in the summer and winter, and creates lake effect snow in colder months. The hills and mountains that border the lake form a bowl, which holds moisture and fog, particularly in the autumn.

Ecology

Although part of a single system, each of the Great Lakes is different. In volume, Lake Superior is the largest. It is also the deepest and coldest of the five. Superior could contain all the other Great Lakes and three more Lake Eries. Because of its size, Superior has a retention time of 191 years, the longest recharge time of the five Lakes.

According to a study by professors at the University of Minnesota Duluth, Lake Superior has been warming faster than its surrounding climate. Summer surface temperatures in the lake have increased about 4.5 degrees Fahrenheit since 1979, compared with about a 2.7-degree increase in the surrounding average air temperature. The increase in the lake’s surface temperature is not only due to climate change but also to the decreasing lack of ice cover. Less winter ice cover allows more solar radiation to penetrate the lake and warm the water.[4]

The Lake Superior Basin is home to many diverse micro-climates, environments, and habitats. Some of the more unusual include the Kakagon Slough, sometimes referred to as the "Everglades of the North," a vast cold water wetland encompassing 16,000 acres. Along with other rare species, the Slough provides nesting areas for the threatened Piping plover, and nurseries for the ever shrinking population of lake sturgeon. Farther north, the Algoma Highlands on the eastern shore of Lake Superior in Ontario is a rare example of old-growth forest. With nearly 30 inches (762 mm) of rainfall and 13 feet (four meters) of snow annually, the forest is one of Canada's most diversified biomes. The Lake Superior Highlands is another setting for an immense range of plant and animal species living in rocky shoreline communities and old-growth hardwood forests. The undisturbed wild lands edging Lake Superior create habitats for black bears, lynxes, migrating raptors, including peregrine falcons and bald eagles. Considered "disjunct," these communities are threatened because the nearest neighboring habitats can be hundreds of miles distant. Considerable effort is being expended to leave these habitats and environments intact despite encroaching development.

Shipping

Lake Superior has been an important link in the Great Lakes Waterway, providing a route for the transportation of iron ore and other mined and manufactured materials. Large cargo vessels called lake freighters, as well as smaller ocean-going freighters, transport these commodities across Lake Superior. Cargo as varied as taconite, coal, chromium ore, wheat, corn, beet pulp pellets, salt, and wind turbine parts travel across Lake Superior in one month.

Shipwrecks

The last major shipwreck on Lake Superior was that of SS Edmund Fitzgerald, in 1975.

According to an old sailor's tale, Lake Superior never gives up her dead. This is due to the temperature of the water. Normally, bacteria feeding off a sunken decaying body will generate gas inside the body, causing it to float to the surface after a few days. The water in Lake Superior however, is cold enough year-round to inhibit bacterial growth, meaning bodies tend to sink and never surface.[2] This is poetically referenced in Gordon Lightfoot's famous ballad, "The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald."

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 John W. Wright, (ed.), The New York Times Almanac (New York: Penguin Books, 2004, ISBN 0143038206).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Barbara Chisholm (ed.), Superior: Under the Shadow of the Gods (Lynx Images, 1998, ISBN 978-0969842774).

- ↑ The Soo Locks Pure Michigan. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- ↑ Study: Lake Superior is one of the fastest-warming lakes in the world MPR News, January 14, 2016. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Armbruster, Ann. Lake Superior. New York: Children's Press, 1996. ISBN 0516200151.

- Beckett, Harry. Lake Superior. Vero Beach, FL: Rourke Corp., 1999. ISBN 0865935289.

- Chisholm, Barbara (ed.), Superior: Under the Shadow of the Gods. Lynx Images, 1998. ISBN 978-0969842774

- Prevost, John F. Lake Superior. Edina, MN: Abdo Pub., 2002. ISBN 1577651049.

- Wright, John W. (ed.). The New York Times Almanac. New York: Penguin Books, 2004. ISBN 0143038206

- Ylvisaker, Anne. Lake Superior. Mankato, MN: Capstone Press, 2004. ISBN 0736822127.

External links

All links retrieved October 21, 2022.

- Lake Superior. United States Environmental Protection Agency.

- Lake Superior Facts

- Lake Superior Magazine

- Lake Superior: Facts About the Greatest Great Lake Live Science.

- Lake Superior Pure Michigan

| North American Great Lakes |

| Lake Superior | Lake Michigan | Lake Huron | Lake Erie | Lake Ontario |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.