| Sioux |

|---|

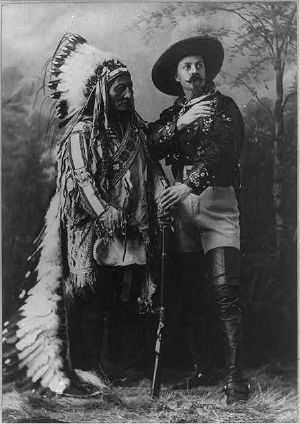

Photograph of Sitting Bull, a Hunkpapa Lakota chief and holy man, circa 1885 |

| Total population |

| 170,110[1] |

| Regions with significant populations |

| United States of America (SD, MN, NE, MT, ND), Canada (MB, SK, AB) |

| Languages |

| English, Sioux |

| Religions |

| Christianity (incl. syncretistic forms), Midewiwin |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Assiniboine, Stoney (Nakoda), and other Siouan peoples |

The Sioux (IPA /su/) are a Native American and First Nations people. The term can refer to any ethnic group within the Great Sioux Nation or any of the nation's many dialects. The Sioux nation was and is comprised of three major subdivisions: generally known as the Lakota, the Dakota, and the Nankota.

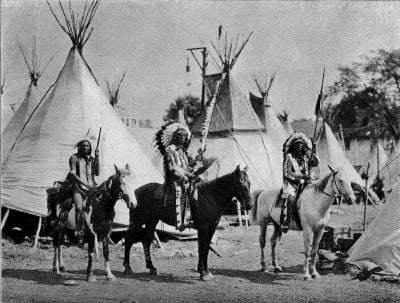

The images that have become the standard of American Indiansâwearing long eagle-feathered war bonnets and fringed leather clothing with colorful beadwork, living in tipis, and riding on horseback across the plains, hunting buffalo and fighting the Unites States armyâdepict the Sioux, particularly the Lakota. The Sioux offered the most resolute resistance to white invasions into their land, and violent reactions to violations of treaties. Their variation on the Ghost Dance aroused fear and hostility in the white Americans, with the Sioux continuing their practice despite its banning by the US authority. The famous incidents of bloodshed in American history, the Battle of the Little Bighorn (also known as Custer's Last Stand) and the Wounded Knee Massacre, both involved the Sioux.

Today, the Sioux maintain many separate tribal governments scattered across several reservations and communities in North and South Dakota, Minnesota, Nebraska, and also in Manitoba and southern Saskatchewan in Canada. The Sioux have rebuilt their lives after their difficult course of suffering and bloodshed. They have revived their religious beliefs and practice traditional ceremonies and crafts, and encourage traditional values among the youth. Many live in urban areas; others have established casinos to bring revenue to their reservation. While the path of the Sioux is still not smooth, many have made effort to unite with other Indian groups and with the American culture, seeking to resolve the past divisions and find a way of harmony and prosperity for all.

Introduction

The Sioux comprise three major divisions based on dialect and subculture:

- Teton (âDwellers on the Prairieâ): the westernmost Sioux, known for their hunting and warrior culture, and are often referred to as the Lakota.

- Isanti ("Knife," originating from the name of a lake in present-day Minnesota): residing in the extreme east of the Dakotas, Minnesota, and northern Iowa, and are often referred to as the Santee or Dakota.

- Ihanktowan-Ihanktowana ("Village-at-the-end" and "little village-at-the-end"): residing in the Minnesota River area, they are considered to be the middle Sioux, and are often referred to as the Yankton-Yanktonai or Nakota.

The term Dakota has also been applied by anthropologists and governmental departments to refer to all Sioux groups, resulting in names such as Teton Dakota, Santee Dakota, and so forth. This was due in large part to the misrepresented translation of the Ottawa word from which Sioux is derived (supposedly meaning "snake").[2] The name "Sioux" is an abbreviated form of Nadouessioux borrowed into French Canadian from NadoĂźessioĂźak from the early Ottawa exonym: naâ˘toweâ˘ssiwak "Sioux." It was first used by Jean Nicolet in 1640.[3] The Proto-Algonquian form *nÄtowÄwa meaning "Northern Iroquoian" has reflexes in several daughter languages that refer to a small rattlesnake (massasauga, Sistrurus).[4]

The name Lakota comes from the Lakota autonym, lakhĂłta "feeling affection, friendly, united, allied." The early French literature does not distinguish a separate Teton division, instead putting them into a "Sioux of the West" group with other Santee and Yankton bands.

History

The earliest known European record of the Sioux was in Minnesota, Iowa, and Wisconsin.[4] Furthermore, after the introduction of the horse, the Sioux dominated larger areas of landâfrom present day Canada to the Platte River, from Minnesota to the Yellowstone River, including the Black Hills and the Powder River country.[5]

Alliance with French fur merchants

In the late seventeenth century, the Dakota entered into an alliance with French merchants,[6] who were trying to gain advantage in the struggle for the North American fur trade against the English, who had recently established the Hudson's Bay Company. The Dakota were thus lured into the European economic system and the bloody inter-aboriginal warfare that stemmed from it.

Dakota War of 1862

When 1862 arrived shortly after a failed crop the year before and a winter starvation, the federal payment was late. The local traders would not issue any more credit to the Santee and one trader, Andrew Myrick, went so far as to tell them that they were 'free to eat grass or their own dung'. As a result, on August 17, 1862 the Dakota War of 1862 began when a few Santee men murdered a white farmer and most of his family, igniting further attacks on white settlements along the Minnesota River. The Santee then attacked the trading post, and Myrick was later found among the dead with his mouth stuffed full of grass.[7]

On November 5, 1862 in Minnesota, in courts-martial, 303 Santee Sioux were found guilty of rape and murder of hundreds of Caucasian and European farmers and were sentenced to a hanging. No attorneys or witness were allowed as a defense for the accused, and many were convicted in less than five minutes of court time with the judge.[8] President Abraham Lincoln remanded the death sentence of 284 of the warriors, signing off on the execution of 38 Santee men by hanging on December 26, 1862 in Mankato, Minnesota, the largest mass-execution in US history.[9]

Afterwards, annuities to the Dakota were suspended for four years and the monies were awarded to the white victims. The men who were pardoned by President Lincoln were sent to a prison in Iowa, where more than half died.[8]

Aftermath of Dakota War

During and after the revolt, many Santee and their kin fled Minnesota and Eastern Dakota to Canada, or settled in the James River Valley in a short-lived reservation before being forced to move to Crow Creek Reservation on the east bank of the Missouri. A few joined the Yanktonai and moved further west to join with the Lakota bands to continue their struggle against the United States military.[8]

Others were able to remain in Minnesota and the east, in small reservations existing into the twenty-first century, including Sisseton-Wahpeton, Flandreau, and Devils Lake (Spirit Lake or Fort Totten) Reservations in the Dakotas. Some eventually ended up in Nebraska, where the Santee Sioux Tribe today has a reservation on the south bank of the Missouri. Those who fled to Canada now have descendants residing on eight small Dakota Reserves, four of which are located in Manitoba (Sioux Valley, Long Plain [Dakota Tipi], Birdtail Creek, and Oak Lake [Pipestone]) and the remaining four (Standing Buffalo, Moose Woods [White Cap], Round Plain [Wahpeton], and Wood Mountain) in Saskatchewan.

Red Cloud's War

Red Cloud's War (also referred to as the Bozeman War) was an armed conflict between the Sioux and the United States in the Wyoming Territory and the Montana Territory from 1866 to 1868. The war was fought over control of the Powder River Country in north central Wyoming, which lay along the Bozeman Trail, a primary access route to the Montana gold fields.

The war is named after Red Cloud, a prominent chief of Oglala Sioux who led the war against the United States following encroachment into the area by the U.S. military. The war, which ended with the Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868, resulted in a complete victory for the Sioux and the temporary preservation of their control of the Powder River country.[10]

Black Hills War

Between 1876 and 1877, the Black Hills War took place. The Lakota and their allies fought against the United States military in a series of conflicts. The earliest being the Battle of Powder River, and the final battle being at Wolf Mountain. Included are the Battle of the Rosebud, Battle of the Little Bighorn, Battle of Warbonnet Creek, Battle of Slim Buttes, Battle of Cedar Creek, and the Dull Knife Fight.

Wounded Knee Massacre

The Battle at Wounded Knee Creek was the last major armed conflict between the Lakota and the United States, subsequently described as a "massacre" by General Nelson A. Miles in a letter to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs.[11]

Usage of the Ghost Dance reportedly instigated the massacre. The traditional ritual used in the Ghost Dance, the circle dance, has been used by many Native Americans since pre-historic times, but was first performed in accordance with Jack Wilson's teachings among the Nevada Paiute in 1889. The practice swept throughout much of the American West, quickly reaching areas of California and Oklahoma. As the Ghost Dance spread from its original source, Native American tribes synthesized selective aspects of the ritual with their own beliefs, often creating change in both the society that integrated it and the ritual itself. At the core of the movement was the prophet of peace Jack Wilson, known as Wovoka among the Paiute, who prophesied a peaceful end to white American expansion while preaching messages of clean living, an honest life, and cross-cultural cooperation.

The Sioux variation on the Ghost Dance, however, tended towards millenarianism, an innovation which distinguished their interpretation from Jack Wilson's original teachings.[12] The Lakota interpretation is drawn from the idea of a ârenewed Earthâ in which âall evil is washed away.â This included the removal of all Anglo Americans from their lands, unlike the original version of the Ghost Dance which encouraged harmonious co-existence with Anglos.[13]

In February 1890, the United States government broke a Lakota treaty by adjusting the Great Sioux Reservation of South Dakota (an area that formerly encompassed the majority of the state) into five smaller reservations.[13] This was done to accommodate white homesteaders from the Eastern United States and was in accordance with the governmentâs clearly stated âpolicy of breaking up tribal relationshipsâ and âconforming Indians to the white manâs ways, peaceably if they will, or forcibly if they must.â[14] Once on the reduced reservations, tribes were separated into family units on 320 acre plots, forced to farm, raise livestock, and send their children to boarding schools that forbade any inclusion of Native American traditional culture and language.

To help support the Sioux during the period of transition, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), was delegated the responsibility of supplementing the Sioux with food and hiring white farmers as teachers for the people. The farming plan failed to take into account the difficulty Sioux farmers would have in trying to cultivate crops in the semi-arid region of South Dakota. By the end of the 1890 growing season, a time of intense heat and low rainfall, it was clear that the land was unable to produce substantial agricultural yields. Unfortunately, this was also the time when the governmentâs patience with supporting the so-called âlazy Indiansâ ran out, resulting in rations to the Sioux being cut in half. With the buffalo virtually eradicated from the plains a few years earlier, the Sioux had no options available to escape starvation.

Increased performances of the Ghost Dance ritual ensued, frightening the supervising agents of the BIA. Kicking Bear was forced to leave Standing Rock, but when the dances continued unabated, Agent McLaughlin asked for more troops, claiming that Hunkpapa spiritual leader Sitting Bull was the real leader of the movement. A former agent, Valentine McGillycuddy, saw nothing extraordinary in the dances and ridiculed the panic that seemed to have overcome the agencies, saying: âThe coming of the troops has frightened the Indians. If the Seventh-Day Adventists prepare the ascension robes for the Second Coming of the Savior, the United States Army is not put in motion to prevent them. Why should not the Indians have the same privilege? If the troops remain, trouble is sure to come.â[15]

Nonetheless, thousands of additional U.S. Army troops were deployed to the reservation. On December 15, 1890, Sitting Bull was arrested on the reservation for failing to stop his people from practicing the Ghost Dance.[13] During the incident, a Sioux witnessing the arrest fired at one of the soldiers prompting an immediate retaliation; this conflict resulted in deaths on both sides, including the loss of Sitting Bull himself.

Big Foot, a Miniconjou leader on the U.S. Armyâs list of trouble-making Indians, was stopped while en route to convene with the remaining Sioux chiefs. U.S. Army officers forced him and his people to relocate to a small camp close to the Pine Ridge Agency so that the soldiers could more closely watch the old chief. That evening, December 28-, the small band of Sioux erected their tipis on the banks of Wounded Knee Creek. The following day, during an attempt by the officers to collect any remaining weapons from the band, one young and deaf Sioux warrior refused to relinquish his arms. A struggle followed in which somebody's weapon discharged into the air. One U.S. officer gave the command to open fire and the Sioux responded by taking up previously confiscated weapons; the U.S. forces responded with carbine firearms and several rapid fire light artillery (Hotchkiss) guns mounted on the overlooking hill. When the fighting had concluded, 25 U.S. soldiers lay dead amongst the 153 dead Sioux, most of whom were women and children.[13] Some of the soldiers are believed to have been the victims of "friendly fire" as the shooting took place at point blank range in chaotic conditions.[16] Around 150 Lakota are believed to have fled the chaos, many of whom may then have died from hypothermia.

Reservation life

After the Massacre at Wounded Knee the spirit of the Sioux was crushed. They retreated and accepted reservation life in exchange for the rest of their lands, and domestic cattle and corn in exchange for buffalo. Red Cloud became an important leader of the Lakota as they transitioned from the freedom of the plains to the confinement of the reservation system. He outlived the other major Sioux leaders of the Indian wars and died in 1909 on the Pine Ridge Reservation, where he is buried.

Languages

The earlier linguistic three-way division of the Dakotan branch of the Siouan family identified Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota as dialects of a single language, where Lakota = Teton, Dakota = Santee and Yankton, Nakota = Yanktonai & Assiniboine. This classification was based in large part on each group's particular pronunciation of the autonym DakhĂłta-LakhĂłta-NakhĂłta, meaning the Yankton-Yanktonai, Santee, and Teton groups all spoke mutually intelligible varieties of a Sioux idiom.[4] However, more recent study identifies Assiniboine and Stoney as two separate languages with Sioux being the third language that has three similar dialects: Teton, Santee-Sisseton, Yankton-Yanktonai.

Derived names

The U.S. states of North Dakota and South Dakota are named after the Dakota tribe. One other U.S. state has a name of Siouan origin: Minnesota is named from mni ("water") plus sota ("hazy/smoky, not clear"), and the name Nebraska comes from the related Chiwere language. Furthermore, the states Kansas, Iowa, and Missouri are named for cousin Siouan tribes, the Kansa, Iowa, and Missouri, respectively, as are the cities Omaha, Nebraska and Ponca City, Oklahoma. The names vividly demonstrate the wide dispersion of the Siouan peoples across the Midwest U.S.

More directly, several Midwestern municipalities utilize Sioux in their names, including Sioux City, Iowa, Sioux Center, Iowa, and Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Midwestern rivers include the Little Sioux River in Iowa and Big Sioux River along the Iowa/South Dakota border.

Many smaller towns and geographic features in the Northern Plains retain their Sioux names or English translations of those names, including Wasta, Owanka, Oacoma, Rapid City (Mne luza: "cataract" or "rapids"), Sioux Falls/Minnehaha County (Mne haha: "waterfall"), Belle Fourche (Mniwasta, or "Good water"), Inyan Kara, Sisseton (Sissetowan: tribal name), Winona ("first daughter"), etc.

Culture

Political organization

The historical political organization was based on the participation of individuals and the cooperation of many to sustain the tribeâs way of life. Leadership was chosen from noble birth and through demonstrations of bravery, fortitude, generosity, and wisdom.[2]

Societies

The leadership positions were usually hereditary with future leaders being chosen by their war record and generosity. Tribal leaders were members of the Naca Ominicia society and decided matters of tribal hunts, camp movements, whether to make war or peace with their neighbors, or any other community action.[5] Societies were similar to fraternities, whereas the men joined to raise their position in the tribe. Societies were composed of smaller clans and varied in number among the seven divisions. There were two types of societies: Akicita, for the younger men, and Naca, for elders and former leaders.[2]

Akicita societies

Akicita societies put their efforts into training men as warriors, participating in tribal hunts, policing, and upholding civility among the community. There were many smaller Akicita societies, including the Kit-Fox, Strong Heart, Elk, and so on.[5]

Naca societies

Leaders in the Naca societies, per Naca Ominicia, were the tribal elders and leaders, who would elect seven to ten men, depending on the division, called Wicasa Itacans. The Wicasa Itacans interpreted and enforced the decisions of the Naca.[5]

The Wicasa Itacans would elect two to four Shirt Wearers who were the voice of the Wicasa. Concerned with the welfare of the nation, they could settle quarrels among families or with foreign nations, among their responsibilities. Shirt Wearers were generally elected from highly respected sons of the leaders; however, men with obscure parents who displayed outstanding leaderships skills and had earned the respect of the community could be elected, exemplified by Crazy Horse.[2]

Under the Shirt Wearers were the Wakincuza, or Pipe Holders. They held a prominent position during peace ceremonies, regulated camp locations, and supervised the Akicita societies during buffalo hunts.[5]

Religion

Spiritual beings

Lakota mythology was complex, with numerous spiritual beings. Animist beliefs were an important part of a their life, as they believed that all things possessed spirits. Their worship was centered on one main god, in the Sioux language Wakan Tanka (the Great Spirit). The Great Spirit had power over everything that had ever existed. Earth was also important, as she was the mother of all spirits.

- Wakan Tanka

In the Sioux tradition, Wakan Tanka (correct Siouan spelling WakaĹ TČaĹka) is the term for the "sacred" or the "divine." It is often translated as "The Great Spirit." However, its meaning is closer to "Great Mystery" as Lakota spirituality is not monotheistic. Before the attempted conversion to Christianity, WakaĹ TČaĹka was used to refer an organization of sacred entities whose ways were mysterious; thus the meaning of "the Great Mystery." It is typically understood as the power or the sacredness which resides in everything, similar to many animistic and pantheistic notions. This term describes every creature and object as wakan ("holy") or having aspects that are wakan.

- Iktomi

Another important spiritual being is Iktomi, a spider-trickster spirit, and a culture-hero for the Lakota people. According to the Lakota, Iktomi is the son of Inyan, the rock spirit. His appearance is that of a spider, but he can take any shape, including that of a human. When he is a human he is said to wear red, yellow and white paint, with black rings around his eyes. Iktomi is the tricksterâaccording to tradition, in the ancient days, Iktomi was Ksa, or wisdom, but he was stripped of this title and became Iktomi because of his troublemaking ways. He began playing malicious tricks because people would jeer at his strange or funny looks. Most of his schemes end with him falling into ruin when his intricate plans backfire. These tales are usually told as a way to teach lessons to Lakota youth. Because it is Iktomi, a respected (or perhaps feared) deity playing the part of the idiot or fool, and the story is told as entertainment, the listener is allowed to reflect on misdeeds without feeling like they are being confronted. In other tales, Iktomi is depicted with dignity and seriousness, such as in the popularized myth of the dreamcatcher.

Sun Dance

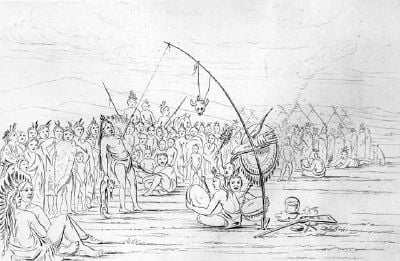

The Sun Dance is a ceremony practiced by a number of Native Americans, and was one of the most important rituals practiced by Plains Indians. The ceremony involves dancing, singing, praying, drumming, the experience of visions, fasting, and in some cases piercing of the chest or back. During the Sun Dance, a Heyoka sacred clown may appear to tempt the dancers with water and food and to dance backwards around the circle in a show of respect. Frederick Schwatka wrote about a Sioux Sun Dance he witnessed in the late 1800s:

Each one of the young men presented himself to a medicine-man, who took between his thumb and forefinger a fold of the loose skin of the breastâand then ran a very narrow-bladed or sharp knife through the skinâa stronger skewer of bone, about the size of a carpenter's pencil was inserted. This was tied to a long skin rope fastened, at its other extremity, to the top of the sun-pole in the center of the arena. The whole object of the devotee is to break loose from these fetters. To liberate himself he must tear the skewers through the skin, a horrible task that even with the most resolute may require many hours of torture (Schwatka 1889).

In fact, the object of being pierced is to sacrifice one's self to the Great Spirit, and to pray while connected to the Tree of Life, a direct connection to the Great Spirit. Breaking from the piercing is done in one moment, as the man runs backwards from the tree at a time specified by the leader of the dance. A common explanation, in context with the intent of the dancer, is that a flesh offering, or piercing, is given as part of prayer and offering for the improvement of one's family and community.

Heyoka

Heyoka refers to the Lakota concept of a contrarian, jester, satirist or sacred clown. Their formalized role as comedic entertainers is referred to as a clown society. The Heyoka symbolize and portray many aspects of the sacred, the Wakan, and specifically may represent the trickster character in religious ceremonies. Other times their purpose is only to parody excessive seriousness, or to deflate pomposity. Their satire presents important questions by fooling around.

Heyoka are thought of as being backwards-forwards, upside-down, or contrary in nature. This is often manifest by doing things backwards or unconventionallyâriding a horse backwards, wearing clothes inside-out, or speaking in a backwards language. For example, if food were scarce, a Heyoka would sit around and complain about how full he was; during a baking hot heat wave a Heyoka would shiver with cold and put on gloves and cover himself with a thick blanket. Similarly, when it is 40 degrees below freezing he will wander around naked for hours complaining that it is too hot. A unique example is the famous Heyoka sacred clown called "the Straighten-Outer":

He was always running around with a hammer trying to flatten round and curvy things (soup bowls, eggs, wagon wheels, etc.), thus making them straight.[17]

Sioux music

Among the Dakota, traditional songs generally begin in a high pitch, led by a single vocalist (solo) who sings a phrase that is then repeated by a group. This phrase then cascades to a lower pitch until there is a brief pause. Then, the song's second half, which echoes the first, is sung (incomplete repetition). The second part of the song often includes "honor beats," usually in the form of four beats representing cannon fire in battle. The entire song may be repeated several times, at the discretion of the lead singer.

Many songs use only vocables, syllabic utterances with no lexical meaning. Sometimes, only the second half of the song has any lyrics.

In some traditional songs, women sing one octave above the men, though they do not sing the first time the song is sung or the lead line at any time.

Percussion among the Dakota use drums, sometimes with syncopation. In competition songs, beats start off irregular and are then followed by a swift regular beat.

The Dakota Flag Song begins special events, such as powwows, and is not accompanied by a dance. Other kinds of songs honor veterans, warriors or others, or are sacred in origin, such as inipi songs.

Contemporary Sioux

Today, one half of all enrolled Sioux in the United States live off the reservation. Also, to be an enrolled member in any of the Sioux tribes in the United States, 1/4 degree is required.[18]

Today many of the tribes continue to officially call themselves Sioux which the Federal Government of the United States applied to all Dakota/Lakota/Nakota people in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. However, some of the tribes have formally or informally adopted traditional names: the Rosebud Sioux Tribe is also known as the SiÄangu Oyate (BrulĂŠ Nation), and the Oglala often use the name Oglala Lakota Oyate, rather than the English "Oglala Sioux Tribe" or OST. (The alternative English spelling of Ogallala is considered improper).[3] The Lakota have names for their own subdivisions.

The Sioux maintain many separate tribal governments scattered across several reservations and communities in the Dakotas, Minnesota, Nebraska, and also in Manitoba and southern Saskatchewan in Canada. In Canada, the Canadian government recognizes reserves as "First Nations."

Lakota

The Lakota (IPA: [laËkËŁota]) (also Lakhota, Teton, Titonwon) are a Native American tribe. They form one of a group of seven tribes (the Great Sioux Nation) and speak Lakota, one of the three major dialects of the Sioux language.

The Lakota are the westernmost of the three Sioux groups, occupying lands in both North and South Dakota. The seven branches or "sub-tribes" of the Lakota are BrulĂŠ, Oglala, Sans Arcs, Hunkpapa, Miniconjou, Sihasapa, and Two Kettles.

Yankton-Yanktonai (Nakota)

The Ihanktowan-Ihanktowana, or the Yankton ("campers at the end") and Yanktonai ("lesser campers at the end") divisions consist of two bands or two of the seven council fires. According to Nasunatanka and Matononpa in 1880, the Yanktonai are divided into two sub-groups known as the Upper Yanktonai and the lower Yanktonai (Hunkpatina).[4]

Economically, they were involved in quarrying pipestone. The Yankton-Yanktonai moved into northern Minnesota. In the 1700s, they were recorded as living in the Mankato region of Minnesota.[19]

Santee (Dakota)

The Santee people migrated north and westward from the south and east into Ohio then to Minnesota. The Santee were a woodland people who thrived on hunting, fishing and subsistence farming. Migrations of Anishinaabe/Chippewa people from the east in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, with muskets supplied by the French and British, pushed the Santee further into Minnesota and west and southward, giving the name "Dakota Territory" to the northern expanse west of the Mississippi and up to its headwaters.[4]

Teton (Lakota)

The western Santee obtained horses, probably in the seventeenth century (although some historians date the arrival of horses in South Dakota to 1720), and moved further west, onto the Great Plains, becoming the Titonwan tribe, subsisting on the buffalo herds and corn-trade with their linguistic cousins, the Mandan and Hidatsa along the Missouri.[4]

Famous Sioux

Historical

- Taoyateduta (Little Crow) (ca. 1810âJuly 3, 1863)âChief famous for role in the Dakota War of 1862

- Tatanka Iyotanke (Sitting Bull)(1831-1890)âChief famous for role in the Battle of the Little Bighorn

- Makhpiya-luta (Red Cloud)(ca. 1819-1909)âChief famous for role in Red Cloud's War

- Tasunka Witko (Crazy Horse)(1849-1877)âFamous for leadership and courage in battle

- Hehaka Sapa (Black Elk)âLakota holy man, source of Black Elk Speaks and other books

- Tahca Ushte (Lame Deer)âLakota holy man, carried traditional knowledge into modern era

- Charles EastmanâAuthor, physician and reformer

- Colonel Gregory "Pappy" BoyingtonâWorld War II Fighter Ace and Medal of Honor recipient; (one quarter Sioux)

Modern

- Robert "Tree" Cody, Native American flutist (Dakota)

- Elizabeth Cook-Lynn, activist, academic, and writer

- Mary Crow Dog, writer and activist

- Vine Deloria, Jr., activist and essayist

- Indigenous, blues band (Nakota)

- Illinois Jacquet, jazz saxophonist (half Sioux and half African American)

- Russell Means, activist (Oglala)

- Ed McGaa, author, (Oglala) CPT US Marine Corp F-4 Phantom Fighter Pilot

- Eddie Spears, actor (Lakota Sioux Lower Brule)

- Michael Spears, actor (Lakota Sioux Lower Brule)

- John Trudell, actor

- Floyd Red Crow Westerman, singer and actor (Dakota)

- Leonard Peltier, imprisoned for allegedly killing two FBI agents in 1975

Notes

- â The American Indian and Alaska Native Population: 2010 United States Census Data. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- â 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Royal B. Hassrick, The Sioux: Life and Customs of a Warrior Society (University of Oklahoma Press, 1964, ISBN 0806106077).

- â 3.0 3.1 Michael Johnson, The Tribes of the Sioux Nation (Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2000, ISBN 185532878X).

- â 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Stephen R. Riggs, Dakota Grammar: With Texts and Ethnography (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0873514729).

- â 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Thomas E. Mails, Dog Soldiers, Bear Men, and Buffalo Women: A Study of the Societies and Cults of the Plains Indians (New York: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1973, ISBN 013217216X).

- â Gerry van Houten, Corporate Canada: An Historical Outline (Progress Books, 1991, ISBN 978-0919396548), 6-7.

- â Mark Steil and Tim Post, Minnesota's Uncivil War. Minnesota's Uncivil War: Let them eat grass Minnesota Public Radio (September 26, 2002). Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- â 8.0 8.1 8.2 Time-Life Books, War for the Plains (Time-Life Books, 1994, ISBN 0809494450).

- â Mark Steil and Tim Post, Minnesota's Uncivil War: Execution and expulsion 'Minnesota Public Radio (September 26, 2002). Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- â Dee Brown, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (Owl Books/Holt, 30th Anniversary Edition, 2001, ISBN 978-0805066692).

- â Letter: General Nelson A. Miles to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, March 13, 1917.

- â Robert Utley, The Last Days of the Sioux Nation (Yale University Press, 1963, ISBN 0300002459).

- â 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Alice Beck Kehoe, The Ghost Dance: Ethnohistory and Revitalization (Waveland Press, 2006, ISBN 978-1577664536)

- â Anthony F.C. Wallace, "Revitalization Movements: Some Theoretical Considerations for Their Comparative Study" American Anthropologist (n.s.) 58(2) (1956): 264-281.

- â Ghost Dance. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- â Karen Strom, The Massacre at Wounded Knee. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- â John Fire Lame Deer and Richard Erdoes, Lame Deer, Seeker of Visions (New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 1972, ISBN 0671553925), 250.

- â Enrollment Ordinance. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- â Amos E. OneRoad and Alanson Skinner, Being Dakota: Tales and Traditions of the Sisseton and Wahpeton (Minnesota Historical Society, 2003, ISBN 087351453X).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brown, Dee. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. Owl Books/Holt, 30th Anniversary Edition, 2001. ISBN 978-0805066692

- Cox, Hank H. Lincoln and the Sioux Uprising of 1862. Nashville, TN: Cumberland House, 2005. ISBN 1581824572

- DeMallie, Raymond, and William Sturtevant (eds.). Handbook of North American Indians, Volume 13: Plains, Pt. 1 and Pt. 2. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 2001. ISBN 978-0160504006

- Hassrick, Royal B. The Sioux: Life and Customs of a Warrior Society. University of Oklahoma Press, 1964. ISBN 0806106077

- Johnson, Michael. The Tribes of the Sioux Nation. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2000. ISBN 185532878X

- Kehoe, Alice Beck. The Ghost Dance: Ethnohistory And Revitalization. Waveland Press, 2006. ISBN 978-1577664536

- Lame Deer, John (Fire), and Richard Erdoes. Lame Deer, Seeker of Visions. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 1972. ISBN 0671553925

- Mails, Thomas E. Dog Soldiers, Bear Men, and Buffalo Women: A Study of the Societies and Cults of the Plains Indians. New York: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1973. ISBN 013217216X

- Matson, William, and Mark Frethem. "The Authorized Biography of Crazy Horse and His Family Part One: Creation, Spirituality, and the Family Tree." The Crazy Horse family tells their oral history and with explanations of Lakota spirituality and culture on DVD. Reelcontact.com, 2006.

- OneRoad, Amos E., and Alanson Skinner. Being Dakota: Tales and Traditions of the Sisseton and Wahpeton. Minnesota Historical Society, 2003. ISBN 087351453X

- Riggs, Stephen R. Dakota Grammar: With Texts and Ethnography. Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0873514729

- Time-Life Books. War for the Plains. Time-Life Books, 1994. ISBN 0809494450.

- Utley, Robert M. The Last Days of the Sioux Nation. Yale University, 1963. ISBN 0300002459

- van Houten, Gerry. Corporate Canada: An Historical Outline. Progress Books, 1991. ISBN 978-0919396548

- Waldman, Carl. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. Checkmark Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0816062744

- Wallace, Anthony F.C. "Revitalization Movements: Some Theoretical Considerations for Their Comparative Study." American Anthropologist (n.s.) 58(2): 264-281. (1956)

External links

All links retrieved November 22, 2023.

- Lakota Language Consortium

- Standing Rock Sioux Tribe

- Sioux Treaty of 1868 National Archives

- The Dakota People Historic Fort Snelling

| ||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Sioux history

- Lakota_people history

- Sioux_music history

- Wakan_Tanka history

- Iktomi history

- Heyoka history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.