Kiowa

| Kiowa |

|---|

| Three Kiowa men, 1898 |

| Total population |

| 12,000 |

| Regions with significant populations |

| United States (Oklahoma) |

| Languages |

| English, Kiowa |

| Religions |

| Traditional |

| Related ethnic groups |

| other Tanoan peoples |

The Kiowa are a nation of Native Americans who lived mostly in north Texas, Oklahoma, and eastern New Mexico at the time of the arrival of Europeans, having migrated from their earlier homeland in Montana. The name "Kiowa" was designated at the time of European contact; contemporary Kiowa call themselves Kaui-gu, meaning the "principal people" or "main people." Today, the Kiowa Tribe is federally recognized, with about 12,000 members living in southwestern Oklahoma.

The Kiowa were once a dominant force in the Southern Plains, known as fierce warriors and effectively using their horses for hunting and fighting. However, they were crushed by both military and cultural pressures from the United States in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Despite the loss of land and control over their lives, the Kiowa survived and have emerged as a leader among Native American peoples. They achieved a balance between preserving many aspects of their traditional culture through art, song, and dance, while also progressing in education and economic development for the future. Essentials of their old ways, such as the Sun Dance and their pictographic art on animal skins, may have passed, but their legacy lives on in the spirit of many contemporary Kiowas and continues to be offered to the world by their talented writers and artists.

History

According to historic accounts the Kiowa originally resided in Montana, in the northern basin of the Missouri River. The Crow Nation first met them in the Pryor Mountains. With permission of the Crow, the Kiowa then migrated east to the Black Hills, around 1650. There they acquired the sacred Tai-me or "Sundance Medicine" from their Crow allies. At this time, they used dogs and travois for travel, as was the custom of the Northern peoples.

Then, pushed southward by the invading Cheyenne and Sioux, who were being moved out of their lands in the Great Lakes regions by the Ojibwa tribes, the Kiowa moved down the Platte River basin to the Arkansas River area. There, they fought with the Comanche, who already occupied the land. In this area they acquired horses, dramatically changing the Kiowa lifestyle into that of the Plains Indians.

In the early spring of 1790, at the place that would become Las Vegas, New Mexico, a Kiowa party led by war leader Guikate made an offer of peace to a Comanche party while both were visiting the home of a friend of both tribes. This led to a later meeting between Guikate and the head chief of the Nokoni Comanches. The two groups made an alliance to share the same hunting grounds, and entered into a mutual defense pact. From that time on, the Comanche and Kiowa hunted, traveled, and made war together. An additional group, the Plains Apache (also called Kiowa-Apache), affiliated with the Kiowa at this time.

From their hunting grounds south of the Arkansas River the Kiowa were notorious for long-distance raids as far west as the Grand Canyon region, south into Mexico and Central America, and north into Canada. They were fierce warriors and killed numerous white settlers and soldiers as well as members of other native tribes.

The Indian Wars

After 1840, the Kiowa, with their former enemies the Cheyenne, as well as their allies the Comanche and the Apache, fought and raided the Eastern natives then moving into the Indian Territory. The United States military intervened, and in the Treaty of Medicine Lodge of 1867, the Kiowa agreed to settle on a reservation in southwestern Oklahoma. In return, the Kiowa and their allies were to be protected from the white hunters that were invading the buffalo range, issued certain annuities, provided with schools, churches, farming implements, and generally taught how to live in the style of European settlers. This treaty changed the status of the Kiowa and their allies from that of independent tribes with free and unrestricted range over the plains to dependency on the government, confined to the narrow limits of a reservation and subject to constant military and civilian supervision.

Some bands of Kiowa and others rejected the end of their traditional lifestyle, remaining at large for several years. In 1871, Kiowa leaders Satanta (White Bear), Satank (Sitting Bear), and Big Tree were accused, arrested, transported, and confined at Fort Richardson, Texas, after being convicted by a "cowboy jury" in Jacksboro, Texas, for participating in the Warren Wagon Train Raid. During the transport to Fort Richardson, Texas, Satank, preferring to die fighting rather than be imprisoned, and was shot by accompanying cavalry troops in an escape attempt near Fort Sill, Indian Territory.

In 1874, war parties made up of young Cheyennes, Arapahos, Comanches, and Kiowas who refused to live on the reservations, frustrated and angered by the greatly diminished buffalo herd, attacked white hunters and settlers. Defeated by the cavalry in 1875, seventy-three of those considered most dangerous were rounded up and taken from Fort Sill, Oklahoma, to Fort Marion in Florida. There, several of these warriors developed what has become known as "Plains Indian ledger art."

Culture

After their migrations, the Kiowa lived a typical Plains Indian lifestyle. Mostly nomadic, they survived on buffalo meat and gathered vegetables, lived in tipis, and depended on their horses for hunting and military uses. The buffalo were essential to the Kiowa, providing food and raw materials for living necessities such as shelter and clothing.

Warrior societies

Like other Plains tribes, the Kiowa organized warrior societiesâexclusive groups of those who have proven their courage and skills in fighting. These societies were called "Dog Soldiers" because of visions and dreams of dogs.

The Koitsenko, or "Principal Dogs," was a group of the ten greatest warriors of the Kiowa tribe as a whole, were elected from the five adult warrior societies. The leader wore a long sash and when the Kiowa were engaged in battle he dismounted from his horse and fastened the sash to the earth with his spear. He then fought on the ground there, shouting encouragement to the other warriors. He could not leave that place, even when wounded and in the greatest danger, until another Principal Dog removed the spear (Waldman, 2006). Probably the most famous of the Koitsenko was the great war leader Satank, who died fighting for his freedom.

Art

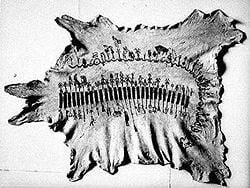

Kiowa ledger art derives from a historical tradition that used traditional pictographs to keep historical records and serve as mnemonic reminders for storytelling. A traditional male art form, Plains Indian warriors drew pictographic representations of heroic deeds and sacred visions, which served to designate their positions in the tribe. Traditionally the artist's medium for their pictographic images were rocks and animal skins, but for the Kiowa in captivity the lined pages of the white man's record keeping books (ledgers) became a popular substitute, hence the name, "ledger art."

The earliest of these Kiowa artists were held in captivity by the U.S. Army at Fort Marion in St. Augustine, Florida, at the conclusion of the Southern Plains Indian war. Captain Richard Henry Pratt was sympathetic and very liberal for his time, wanting to educate his captives and make them self-sufficient. At Fort Marion, he initiated an educational experiment as an alternative to standard imprisonment, culminating in his founding of the Carlisle Indian School in 1879. Throughout their incarceration, the Plains Indian leaders followed Pratt's rules and met his educational demands even as they remained true to their own identities, practicing traditional dances and ceremonies (Lookingbill 2006). In addition to regular studies Pratt encouraged them to pursue their native arts and to sell the products, keeping the profits for themselves. As a result, many of the Kiowa achieved self-sufficiency, as well as developing their art form into the now famous ledger art. For these former warriors their art was not just a way of making money but a form of resistance. The warrior-artists of Fort Marion preserved their history in their traditional pictographic representations, drawn on the the very records, the ledgers, that recorded the expansion of the Euro-American lifestyle. The warrior-artist drawing pictographic representations of his tribal history in a ledger book can be seen as a significant transition from their old traditional identity and finding a place in the new culture, "an attempt to negotiate between oneâs individual/tribal identity and a new dominant cultureâ (Wong 1992).

After the return of the Fort Marion warriors to the reservation there was a withering of this artistic flowering. However, the tradition survived and eventually blossomed again. The most significant ledger book artist was a Kiowa named Haungooah (Silver Horn), whose brother, Ohettoit, was one of the captives in Fort Marion. Silver Horn worked with his brother decorating traditional tipis and then to produce ledger book art work. Silver Horn reputedly influenced both James Auchiah and Stephen Mopope in their work before they became a part of the Kiowa Five, a group of artists who studied at the University of Oklahoma in the 1920s. The "Five" referred to are the male members of the groupâSpenser Asah, James Auchiah, Jack Hokeah, Stephen Mopope, and Monroe Tsatokeâalthough there was a sixth member, a woman named Lois Smokey. Their artistic style is generally recognized as the beginning of the modern Native American Art Movement.

Calendars

Pictorial art was used by the Kiowa as well as other Plains Indians to maintain formal calendar records as well as to illustrate stories. Kiowa calendar keepers kept the history of the tribe in written form by inscribing pictographic records of significant events on animal hides. The Kiowa had a complex calendar system with events recorded for both summer and winter of each year. The Sun Dance ceremony provided the reference point for the summer on these calenders.

A particularly complex calendar produced by Silver Horn (or Haungooah), in 1904, was richly illustrated. Silver Horn's calendar begins with the year 1828 and ends in 1904, with summer and winter pictures for most years. Summers are indicated by a green, forked pole, representing the center pole of the Sun Dance, and winters by a bare tree. Silver Horn was one of the artists employed by James Mooney, an anthropologist with the Smithsonian's Bureau of American Ethnology, who worked on the Kiowa Reservation for many years. The calendar contains many interpretive notes made by Mooney, as he employed the artists to produce illustrations for field notes, not works of art for display. Nevertheless, many such art works have been retained and are considered fine works of art in their own right.

Music

Kiowa music, one of the most heavily recorded Native American musics, is part of the larger Southern Plains Indian music that is heavily influenced by the Omaha, often via the Ponca. Kiowa traditional music is strongly focused on dancing, such as the Sun Dance (k'aw-tow). Courtship is a traditional part of k'aw-tow celebrations, and this facet is often reflected in the music.

Much of Kiowa music is related to their warrior society. The Kiowas' significant contributions to world music include the maintenance of traditions such as the Black Leggins Society, the Oh-Ho-Mah Lodge, the Kiowa Gourd Clan, Peyote songs, and sacred Kiowa hymns (Carney and Foley 2003).

Kiowa music is often noted for its hymns that were traditionally played on the flute. Cornel Pewewardy (flautist and full blood Comanche/Kiowa) is a leading performer of contemporary Kiowa/Southern Plains music, including Kiowa Christian hymns which include prominent glissandos (Broughton and Ellingham 2000).

Gourd Dance

The Gourd Dance originated with the Kiowa tribe. It has spread to many other tribes and societies, most of which do not have the blessing of the Kiowa Elders. The dance in the Kiowa Language is called "ti-ah pi-ah" which means "ready to go, ready to die."

The Kiowa consider this dance as their dance since it was given to them by "Red Wolf." A Kiowa story recounts the tale of a young man who had been separated from the rest of the tribe. Hungry and dehydrated after many days of travel, the young man approached a hill and heard an unusual kind of singing coming from the other side. There he saw a red wolf singing and dancing on its hind legs. The man listened to the songs all afternoon and through the night and when morning came, the wolf spoke to him and told him to take the dance and songs back to the Kiowa people. The "howl" at the end of each gourd dance song is a tribute to the red wolf.

Like pow-wow dancing, Gourd Dancing is performed in a circular arena, around which the dancers take their place. The drum can be placed on the side or in the center of the arena. It is a man's dance. Women participate by dancing in place behind their male counterparts and outside the perimeter formed by the men. During most of the song, the dancers dance in place, lifting their feet in time to the drumbeats, and shaking their rattles from side to side. The rattles, traditionally made from gourds can have peyote-stitch beadwork on the handle.

The Gourd Dance was once part of the Kiowa Sun Dance ceremony.

Sun Dance

The Sun Dance was the most important religious ceremony for the Kiowa, as it was for many other plains Indian People. It was not a ceremony worshiping the sun, but rather derived its name from the practice of gazing upward into the sun. It has also been called the Medicine Dance, because of the ceremonial significance of the event. The Sun Dance was usually held once a year during the summer, usually around the time of the summer solstice, and provided a time not only for ceremonial and religious celebration, but also for gathering of the tribe and sharing of news, as well as individual healing and self-renewal.

The Tai-me Keeper or priest played a central role in the Sun Dance, from decidingâbased on inspiration received in a dreamâwhether the ceremony would be held leading to the preparations. The Tai-me was a small decorated stone figure covered with ermine and feathers. The Kiowa received their first Tai-me figure from an Arapaho man who married into the Kiowa tribe. The Arapaho had originally obtained a Tai-me figure from the Crow Indians during their Sun Dance.

Originally, the Kiowa Sun Dance celebration lasted for about ten days, with six days of preparation, followed by four dancing days. The celebration followed a strict pattern of rituals on each of the ten days. On the dancing days, the dance began at sunrise and the dancer's family selected an artist to paint designs on the dancer's body. Following prayers and ceremonial smokes, the dance continued throughout the day. During the four dancing days, spectators and singers were allowed to leave at midnight, but the dancers were required to remain in the sweat lodge without food or water. The only relief the dancers could receive from the heat of the day were waterlillies to cool their heads and traditional ceremonial food. The Tai-me keeper would also fan the dancers. At certain times dancers would fall unconscious and experience visions. Unlike Sun Dances of other tribes, such as the Sioux, the Kiowa never pierced their skin or shed blood in any way during the ceremony. For them, this was considered taboo and would bring misfortune upon the Kiowa People.

On the final day, offerings were made to the Tai-me for good fortune. The last dance performed by the participants was the buffalo dance, so that those leaving would be protected by the buffalo guardian spirit for the coming year. This prayer was last offered in 1887, when the Kiowa people held their last fully completed Sun dance:

- O Dom-oye-alm-k' hee, Creater of the earth,

- Bless my prayer and heal our land,

- Increase our food, the buffalo power,

- Multiply my people, prolong their lives on earth,

- Protect us from troubles and sickness,

- That happiness and joy may be ours in life,

- That life we live is so uncertain,

- Consider my supplications with kindness,

- For I talk to you as yet living for my people.

While the Sun Dance ceremonies were eventually banned by the United States government at the end of the nineteenth century, and the dance itself is no longer performed today, it still impacts Kiowa life. For example, the ten Kiowa Tah-lee Medicine bundles, which played a central role in the Sun Dance purification rituals are still cared for by tribal members charged with their safe protection. Purification through the use of the sweat lodge continues to this day. Other cultural activities such as the Warrior Society dances and the varied songs and music of the Kiowa have also been maintained.

The "peyote religion" or Native American Church, founded by Comanche Quanah Parker, includes aspects of the traditional Kiowa religion, such as daybreak to daylight rituals and dancing.

Contemporary life

On August 6, 1901, Kiowa land in Oklahoma was opened for white settlement, effectively dissolving the contiguous reservation established in the 1867 treaty. Today, most of the Kiowa lands, now protected as a federal trust area, are located in Caddo County in Oklahoma. Many Kiowa have adopted contemporary professional lifestyles; others practice farming or lease oil rights to their lands.

Despite the efforts of the U.S. government in the nineteenth century to eradicate Kiowa traditional culture and religion, they have managed to maintain their stories, songs, and dances. The traditional Gourd Dance is performed frequently at pow-wows today. Kiowa artists are recognized for the flowering of Native American art. Following the internationally acclaimed work of the Kiowa Five in the 1920s, others continued in this Southern Plains style of painting.

The influence of Kiowa art and the revival of ledger art is illustrated in the early work of Cherokee-Creek female artist Virginia Stroud and Spokane artist George Flett. While Stroud is of Cherokee-Creek descent, she was raised by a Kiowa family and the traditions of that culture, and the influence of the Kiowa tradition is evident in her early pictographic images. Well known Kiowa artists of the later twentieth century include Bobby Hill (White Buffalo), Robert Redbird, Roland N. Whitehorse, and T. C. Cannon. The pictographic art of contemporary and traditional artist Sherman Chaddlesone has again revived the ledger art form that was absent in most of the art of the Second Generation Modernists that had developed since Silverhorn and the Kiowa Five.

In addition to their art and music, several contemporary Kiowas have emerged as successful writers. Kiowa author N. Scott Momaday won the 1969 Pulitzer Prize for his novel House Made of Dawn. Other Kiowa authors include playwright Hanay Geiogamah, poet and filmmaker Gus Palmer, Jr., Alyce Sadongei, and Tocakut.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Berlo, Jane Catherine. 1996. Plains Indian Drawings 1865-1935. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0810937420.

- Boyd, Maurice. 1981. Kiowa Voices: Ceremonial Dance, Ritual, and Song, Vol. 1. Texas Christian University Press. ISBN 978-0912646671.

- Boyd, Maurice. 1983. Kiowa Voices: Myths, Legends and Folktales. Texas Christian University Press. ISBN 978-0912646763.

- Broughton, Simon, and Mark Ellingham. 2000. Rough Guide to World Music Volume Two: Latin and North America, the Caribbean, Asia & the Pacific. ISBN 1858286360.

- Carney, George, and Hugh Foley Jr. 2003. Oklahoma Music Guide: Biographies, Big Hits, and Annual Events. ISBN 1581071043.

- Corwin, Hugh. 1958. The Kiowa Indians, Their History and Life Stories.

- Greene, Candace S. 2002. Silver Horn: Master Illustrator of the Kiowas. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806133072.

- Hoig, Stan. 2000. The Kiowas and the Legend of Kicking Bird. Boulder, CO: The University Press of Colorado. ISBN 0870815644.

- Lookingbill, Brad D. 2006. War Dance at Fort Marion: Plains Indian War Prisoners. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0806137391.

- Mishkin, Bernard. 1988. Rank and Warfare Among The Plains Indians. AMS Press. ISBN 0404629032.

- Momaday, N. Scott. 1977. The Way to Rainy Mountain. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0826304362.

- Mooney, James. 2007. Calender History of the Kiowa Indians. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-0548136461.

- Nye, Colonel W.S. 1983. Carbine and Lance: The Story of Old Fort Sill. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0806118563.

- Richardson, Jane. 1988. Law & Status Among the Kiowa Indians American Ethnological Society Monographs; No 1. AMS Press. ISBN 0404629016.

- Waldman, Carl. 2006. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. New York, NY: Checkmark Books. ISBN 978-0816062744.

- Wong, Hertha Dawn. 1992. Sending My Heart Back Across the Years: Tradition and Innovation in Native American Autobiography. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195069129.

External links

All links retrieved March 3, 2025.

- Kiowa Collection: Selections from the Papers of Hugh Lenox Scott.

- Kiowa-Comanche-Apache Indian Lands.

- Kiowa ledger drawing in the Smithsonian.

- Photographs of Kiowa Indians hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- The Kiowa Five by Les Kruger.

- About The Kiowa Six The Jacobson House Native Art Center.

- Silver Horn Pictorial Calendar National Anthropological Archives and Human Studies Film Archives.

- Kiowa Nation.

- SKAW-TOW The Last Kiowa Sun Dance.

| ||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.