Native Americans in the United States

- This article is about the people indigenous to the United States. For broader uses of "Native American" and related terms, see Indigenous peoples of the Americas.

| Native Americans and Alaska Natives |

|---|

|

| Total population |

| American Indian and Alaska Native One race: 2.5 million[1] In combination with one or more other races: 1.6 million[2] |

| Regions with significant populations |

(predominantly the Midwest and West) |

| Languages |

| American English Native American languages |

| Religions |

| Native American Church Christianity Sacred Pipe Kiva Religion Long House |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Other Indigenous peoples of the Americas |

Native Americans in the United States are the indigenous peoples from the regions of North America now encompassed by the continental United States, including parts of Alaska. They comprise a large number of distinct tribes, and ethnic groups, many of which are still enduring as political communities. There is a wide range of terms used, and some controversy surrounding their use: they are variously known as American Indians, Indians, Amerindians, Amerinds, or Indigenous, Aboriginal or Original Americans.

Many of the indigenous peoples died as a result of the arrival of Europeans, some through disease to which they had no immunity, others through the wars and forced migrations to lands that did not support their traditional lifestyle. Yet, today, these diverse peoples are emerging with a renewed sense of pride in their traditional culture, finding their place in the world as part of the family of humankind.

Introduction

Not all Native Americans come from the contiguous U.S. Some come from Alaska, Hawaii, and other insular regions. These other indigenous peoples, including Arctic/Alaskan Native groups such as the Yupik, Eskimos, and Aleuts, are not always counted as Native Americans, although Census 2000 demographics listed "American Indian and Alaskan Native" collectively. Native Hawaiians (also known as Kanaka Māoli and Kanaka ʻOiwi) and various other Pacific Islander American peoples, such as the Chamorros (Chamoru), can also be considered Native American, but it is not common to use such a designation.

Generally, those Native Americans within the U.S. are grouped according to region. These ethnic groups all share both similarities and also quite stark contrast in terms of culture and lifestyle, and each has a unique history.

The Northeastern tribes such as the Algonquin and the Huron, which both led very similar lifestyles and enjoyed a lucrative fur trade with the French. Both of these tribes were defeated by the fierce Iroquois, who were also similarly adept at trading with the European settlers. All three of these ethnic groups were passionate and war-like clans, sustaining themselves more from warring and trade than hunting and gathering. All three tribes were famous for their birchbark canoes, which enabled them to trade furs and weapons by lakes and rivers.

The Great Plains Indians such as the Blackfoot, Pawnee, and the Sioux were nomadic tribes, following the buffalo herds in seasonal and annual migrations. They lived without horses for thousands of years, maintaining a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, and when the European settlers finally introduced them to horses sometime before 1730, they were thought to be sacred animals and a gift from the heavens. Each of these tribes were fiercely independent, with much emphasis being put on a man's ability to hunt and provide for his family. After countless centuries of oral traditions being passed on, the Blackfoot, Pawnee and the Sioux were extremely adept at being successful warriors.

The Pueblo Indians, such as the Zuni and Hopi tribes, of the southwest were more peaceful people, making decorative pottery for their food supplies, which consisted greatly of wild rice, corn, and squash. They would hunt the desert game, but for the most part did not war with each other like their fierce cousins to the north and northeast. They were incensed by some of the cruel and insensitive missionaries, but could do little to prevent the overwhelming influx of Christianity. The Zuni and Hopi are best known for their decorative basket weaving, and colorful pottery designs. Despite the regional similarities, the Navajo and Apache Indian tribes were more warring than their Zuni and Hopi neighbors, and were famous for their brutality to enemies and condemned criminals. Although violent, they still participated in commerce with the local Spanish settlers and the Comanche tribes.

The Northwestern Coast Indians such as the Haida, Tlingit, and Tsimshian were all hunter-gatherers as well, living off the lush forests, lakes and rivers of the Pacific Northwest. Large game such as moose and caribou was their main food source, and they endured very harsh freezing winter conditions. These northwestern tribes all put a huge emphasis on kinship and family, and shared a sacred communal aspect of their culture.

The Great Basin tribes such as the Paiute, Shoshone, and Ute all shared similar family values and religious rituals, often living in large extended family groups and putting an emphasis on story-telling and oral tradition. These tribes all resisted the encroachment of their land from the European settlers, but ultimately all shared the same coerced relocation experience. The Paiute, Shoshone, and Ute were widely known for their decorative art forms. The Northern Ute, and in particular the Uncompahgre Ute from Colorado, are exceptional artisans and produced extraordinary examples of religious and ceremonial beadwork, unusual art forms, and cunningly designed and decorated weapons of war in their traditional culture. The Ute obtained glass beads and other trade items from early trading contact with Europeans and rapidly incorporated their use into religious, ceremonial, and utilitarian objects. Northern Ute beadwork are some of the finest examples of native American art produced in ancient and modern times by any of the Great Basin tribes.

The Southeastern tribes such as the Choctaw and Seminole had similar lifestyles because of the warm humid tropical environment, but had very different religious viewpoints. The Seminoles held much reverence for their shamans and medicine men, whereas the more superstitious Choctaw more actively participated in worshipping the sun as an ancient deity. The Choctaw were used as code talkers during World War I and World War II, like their Navajo brethren.

Terminology

When Christopher Columbus arrived in the "New World," he described the people he encountered as Indians because he mistakenly believed that he had reached the Indies, the original destination of his voyage. The name Indian (or American Indian) stuck, and for centuries the people who first came to the Americas were collectively called Indians in America, and similar terms in Europe. The problem with this traditional term is that the peoples of India are also known as "Indians." The term "Red Man" was common among the early settlers of New England because the northeastern tribes colored their bodies with red pigments, but later this term became a pejorative and insulting epithet during the western push into America, with the corruption redskin becoming its most virulent form. A usage in British English was to refer to natives of North America as 'Red Indians', though now old fashioned, it is still widely used.

The term Native American was originally introduced in the United States by anthropologists as a more accurate term for the indigenous people of the Americas, as distinguished from the people of India. Because of the widespread acceptance of this newer term in and outside of academic circles, some people believe that "Indians" is outdated or offensive. People from India (and their descendants) who are citizens of the United States are known as Indian Americans.

Criticism of the neologism Native American, however, comes from diverse sources. Some American Indians have misgivings about the term Native American. Russell Means, a famous American Indian activist, opposes the term Native American because he believes it was imposed by the government without the consent of American Indians.[3] Furthermore, some American Indians question the term Native American because, they argue, it serves to ease the conscience of "white America" with regard to past injustices done to American Indians by effectively eliminating "Indians" from the present.[4] Still others (both Indians and non-Indians) argue that Native American is problematic because "native of" literally means "born in," so any person born in the Americas could be considered "native." However, very often the compound "Native American" will be capitalized in order to differentiate this intended meaning from others. Likewise, "native" (small 'n') can be further qualified by formulations such as "native-born" when the intended meaning is only to indicate place of birth or origin.

History

The American Indian tribes of the United States have lived for centuries off the land, and prior to European contact, most Native Americans sustained themselves by hunting and fishing, although quite a few supplemented their diet by cultivating corn, beans, squash, and wild rice. One of the earliest oral accounts of the history of one of the Native American tribes surmises that the Algonquins were from the Atlantic coast, arriving at the "First Stopping Place" near Montreal. While the other Anicinàpe peoples continued their journey up the Saint Lawrence River, the Algonquins settled along the Kitcisìpi (Ottawa River), an important highway for commerce, cultural exchange, and transportation. A distinct Algonquin identity, though, was not fully-realized until after the dividing of the Anicinàpek at the "Third Stopping Place," estimated at about 5000 years ago near present day Detroit in Michigan.

The Iroquois Nation or Iroquois Confederacy was a powerful and unique gathering of Native American tribes that lived prosperously prior to the arrival of Europeans in the area around New York State. In many ways, the constitution that bound them together, the Great Binding Law, was a precursor to the American Constitution. It was received by the spiritual leader, Deganawida (The Great Peacemaker), and assisted by the Mohawk leader, Hiawatha, five tribes came together in adopting it. These were the Cayuga, Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, and Seneca. Later, the Tuscarora joined and this group of six tribes united together under one law and a common council. A constitution known as Gayanashagowa (or "Great Law of Peace") was created by The Iroquois Nation, and has been suggested to have influenced the makers of the American constitution. Most anthropologists have traditionally speculated that this constitution was created between the middle 1400s and early 1600s. However, recent archaeological studies have suggested the accuracy of the account found in oral tradition, which argues that the federation was formed around August 31, 1142 based on a coinciding solar eclipse.

Archaeological sites on Morrison Island near Pembroke, within the territory of the Kitcisìpiriniwak, reveal a 1000-year-old culture that manufactured copper tools and weapons. Copper ore was extracted north of Lake Superior and distributed down to northern New York State. Local pottery artifacts from this period show widespread similarities that indicate the continuing use of the river for cultural exchange throughout the Canadian Shield and beyond. On Morrison Island, at the location of where 5,000-year-old copper artifacts were discovered, the Kitcisìpirini band levied a toll on canoe flotillas descending the river, which proves the American Indians have been flourishing for many millennia prior to European contact.

European colonization

The first Native American group encountered by Christopher Columbus in 1492, were the Island Arawaks (more properly called the Taino). It is estimated that of the 250 thousand to one million Island Arawaks, only about 500 survived by the year 1550, and the group was considered extinct before 1650. Yet DNA studies show that the genetic contribution of the Taino to that region continues, and the mitochondrial DNA studies of the Taino are said to show relationships to the Northern Indigenous Nations, such as Inuit (Eskimo) and others.[5]

In the sixteenth century, Spaniards and other Europeans brought horses to the Americas. Some of these animals escaped and began to breed and increased their numbers in the wild. Ironically, the horse had originally evolved in the Americas, but the early American horse became game for the earliest humans and became extinct about 7000 B.C.E., just after the end of the ice age.[6] The re-introduction of the horse had a profound impact on Native American culture in the Great Plains of North America. As a new mode of travel the horse made it possible for some tribes to greatly expand their territories, exchange goods with neighboring tribes, and more easily capture game.

European settlers brought diseases against which the Native Americans had no natural immunity. Chicken pox and measles, though common and rarely fatal among Europeans, often proved deadly to Native Americans. Smallpox, always a terrible disease, proved particularly deadly to Native American populations. Epidemics often immediately followed European exploration, sometimes destroying entire villages. While precise figures are difficult to ascertain, some historians estimate that up to 80 percent of some Native populations died due to European diseases.[7]

Spanish explorers of the early sixteenth century were probably the first Europeans to interact with the native population of Florida.[8] The first documented encounter of Europeans with Native Americans of the United States came with the first expedition of Juan Ponce de León to Florida in 1513, although he encountered at least one native that spoke Spanish. In 1521, he encountered the Calusa people during a failed colonization attempt in which they drove off the Europeans. In 1526, Lucas Vásquez de Ayllón tried to found a colony in what is now South Carolina, but for multiple reasons it failed after only a year. The remaining slaves of the colony revolted and fled into the wilderness to live among the Cofitachiqui people.

Some European settlers used Native American contacts to further their activities in the fur trade; others sold European technology to the natives, including firearms which fueled tribal wars. Peaceful coexistence was established in some times and places. For example, the careful diplomacy of William Pynchon facilitated the founding of what would become Springfield, Massachusetts in a desirable farming location close to the native Agawam settlement.

Struggles for economic and territorial dominance also continued to result in armed conflict. In some cases these latent conflicts resulted in escalating tensions, gradually followed by escalating multi-party violence. In other cases sudden, relatively unprovoked raids were conducted on native and colonial settlements, which might involve arson, massacre, or kidnapping for slavery.

Pre-existing rivalries among both the Native American tribes and confederacies and the European nations led groups from both continents to find war allies among the others against their traditional enemies. When transatlantic civilizations clashed, better technology (including firearms) and the epidemics decimating native populations gave Europeans a substantial military advantage.

In 1637, the Pequot War erupted in the Massachusetts and Plymouth colonies. Indian Wars in the English colonies would continue on and off into the American Revolution. In the early 1680s, Philadelphia was established by William Penn in the Delaware Valley, which was home to the Lenni-Lenape nation. Chief Tamanend reputably took part in a peace treaty between the leaders of the Lenni-Lenape nation and the leaders of the Pennsylvania colony held under a large elm tree at Shakamaxon.

Four delegates of the Iroquoian Confederacy, the "Indian Kings," traveled to London, England, in 1710 to meet Queen Anne in an effort to cement an alliance with the British. Queen Anne was so impressed by her visitors that she commissioned their portraits by court painter John Verelst. The portraits are believed to be some of the earliest surviving oil portraits of Native American peoples taken from life.[9]

In the Spanish sphere, many of the Pueblo people harbored hostility toward the Spanish, primarily due to their denigration and prohibition of the traditional religion (the Spanish at the time being staunchly and aggressively Roman Catholic). The traditional economies of the pueblos were likewise disrupted when they were forced to labor on the encomiendas of the colonists. However, the Spanish had introduced new farming implements and provided some measure of security against Navajo and Apache raiding parties. As a result, they lived in relative peace with the Spanish following the founding of the Northern New Mexican colony in 1598. In the 1670s, however, drought swept the region, which not only caused famine among the Pueblo, but also provoked increased attacks from neighboring hunter-gatherer tribes—attacks against which Spanish soldiers were unable to defend. Unsatisfied with the protective powers of the Spanish crown, the Pueblo revolted in 1680. In 1692, Spanish control was reasserted, but under much more lenient terms.

Native Americans and African American slaves

There were historical treaties between the European Colonists and the Native American tribes requesting the return of any runaway slaves. For example, in 1726, the British Governor of New York exacted a promise from the Iroquois to return all runaway slaves who had joined up with them. There are also numerous accounts of advertisements requesting the return of African Americans who had married Native Americans or who spoke a Native American language. Individuals in some tribes owned African slaves; however, other tribes incorporated African Americans, slave or freemen, into the tribe. This custom among the Seminoles was part of the reason for the Seminole Wars where the European Americans feared their slaves fleeing to the Natives. The Cherokee Freedmen and tribes such as the Lumbee in North Carolina include African American ancestors.

After 1800, the Cherokees and some other tribes started buying and using black slaves, a practice they continued after being relocated to Indian Territory in the 1830s. The nature of slavery in Cherokee society often mirrored that of white slave-owning society. The law barred intermarriage of Cherokees and blacks, whether slave or free. Blacks who aided slaves were punished with one hundred lashes on the back. In Cherokee society, blacks were barred from holding office, bearing arms, and owning property, and it was illegal to teach blacks to read and write.[10][11]

Relations during and after the American Revolutionary War

During the American Revolutionary War, the newly proclaimed United States competed with the British for the allegiance of Native American nations east of the Mississippi River. Most Native Americans who joined the struggle sided with the British, hoping to use the war to halt further colonial expansion onto Native American land. Many native communities were divided over which side to support in the war. For the Iroquois Confederacy, the American Revolution resulted in civil war. Cherokees split into a neutral (or pro-American) faction and the anti-American Chickamaugas, led by Dragging Canoe.

Frontier warfare during the American Revolution was particularly brutal, and numerous atrocities were committed by settlers and native tribes. Noncombatants suffered greatly during the war, and villages and food supplies were frequently destroyed during military expeditions. The largest of these expeditions was the Sullivan Expedition of 1779, which destroyed more than 40 Iroquois villages in order to neutralize Iroquois raids in upstate New York. The expedition failed to have the desired effect: Native American activity became even more determined.[12]

The British made peace with the Americans in the Treaty of Paris (1783), and had ceded a vast amount of Native American territory to the United States without informing the Native Americans. The United States initially treated the Native Americans who had fought with the British as a conquered people who had lost their land. When this proved impossible to enforce, the policy was abandoned. The United States was eager to expand, and the national government initially sought to do so only by purchasing Native American land in treaties. The states and settlers were frequently at odds with this policy.[13]

Removal and reservations

In the nineteenth century, the incessant Westward expansion of the United States incrementally compelled large numbers of Native Americans to resettle further west, often by force, almost always reluctantly. Under President Andrew Jackson, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which authorized the President to conduct treaties to exchange Native American land east of the Mississippi River for lands west of the river. As many as 100,000 Native Americans eventually relocated in the West as a result of this Indian Removal policy. In theory, relocation was supposed to be voluntary (and many Native Americans did remain in the East), but in practice great pressure was put on Native American leaders to sign removal treaties. Arguably the most egregious violation of the stated intention of the removal policy was the Treaty of New Echota, which was signed by a dissident faction of Cherokees, but not the elected leadership. The treaty was brutally enforced by President Andrew Jackson, which resulted in the deaths of an estimated four thousand Cherokees on the Trail of Tears.

The explicit policy of Indian Removal forced or coerced the relocation of major Native American groups in both the Southeast and the Northeast United States, resulting directly and indirectly in the deaths of tens of thousands. The subsequent process of assimilations was no less devastating to Native American peoples. Tribes were generally located to reservations on which they could more easily be separated from traditional life and pushed into European-American society. Some Southern states additionally enacted laws in the nineteenth century forbidding non-Indian settlement on Indian lands, intending to prevent sympathetic white missionaries from aiding the scattered Indian resistance.

At one point, President Jackson told people to kill as many bison as possible in order to cut out the Plains Indians' main source of food.

Conflicts, generally known as "Indian Wars," broke out between U.S. forces and many different tribes. U.S. government authorities entered numerous treaties during this period, but later abrogated many for various reasons. Well-known military engagements include the Native American victory at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876 and the massacre of Native Americans at Wounded Knee in 1890. This, together with the near-extinction of the American Bison that many tribes had lived on, set about the downturn of Prairie Culture that had developed around the use of the horse for hunting, travel, and trading.

American policy toward Native Americans has been an evolving process. In the late nineteenth century, reformers, in efforts to "civilize" or otherwise assimilate Indians (as opposed to relegating them to reservations), adapted the practice of educating native children in Indian Boarding Schools. These schools, which were primarily run by Christian missionaries, often proved traumatic to Native American children, who were forbidden to speak their native languages, taught Christianity instead of their native religions and in numerous other ways forced to abandon their various Native American identities and adopt European-American culture.

The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 gave United States citizenship to Native Americans, in part because of an interest by many to see them merged with the American mainstream, and also because of the heroic service of many Native American veterans in World War I.

Culture

Though cultural features, language, clothing, and customs vary enormously from one tribe to another, there are certain elements which are encountered frequently and shared by many tribes. Many American Indians upheld hunter-gatherer nomadic ways of life, following the herds which sustained them. Among all of the Native American ethnic groups, the most common implements were the bow and arrow, the war club, and the spear. Quality, materials, and designs varied widely.

Large mammals like mammoths and mastodons were largely extinct by around 8000 B.C.E., and the Native Americans switched to hunting other large game, such as buffalo. Early hunter-gatherer tribes made stone weapons from around 10,000 years ago; as the age of metallurgy dawned, newer technologies were used and more efficient weapons produced. The Great Plains tribes were still hunting the bison when they first encountered the Europeans. The acquisition of the horse and horsemanship from the Spanish in the seventeenth century greatly altered the natives' culture, changing the way in which these large creatures were hunted and making them a central feature of their lives.

Many tribes had a chieftain or village leader known as a sachem. Many tribes had no centralized form of government or chief, but would band together with neighboring communities that shared similar lifestyles. The right of electing its sachem and chiefs was done often either by a democratic and unanimous vote, usually one who was widely known in the tribe for conquests in war and hunting, or by hereditary inheritance. The right to bestow any name upon the tribal children as well as adopting children and marrying outside of the tribe was also a common facet. Many ethnic groups celebrated very similar oral traditions of story-telling, religious practices, and ritualistic dancing. Subdivision and differentiation took place between various groups. Upwards of 40 stock languages developed in North America, with each independent tribe speaking a dialect of one of those languages. Some functions and attributes of tribes are the possession of a territory and a name, maintaining the exclusive possession of a dialect.

Housing

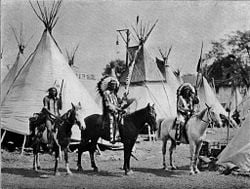

In many instances, American Indian beliefs were symbolized in their dwelling structures. The more migratory tribes such as the Omaha lived in earth lodges, which were quite ingenious structures with a timber frame and a thick soil covering. At the center of the lodge was a fireplace that recalled their creation myth. The earth lodge entrance faced east, to catch the rising sun and remind the people of their origin and migration upriver. The circular layout of tribal villages reflected the tribe's beliefs. Sky people lived in the north half of the village, the area that symbolized the heavens. Earth people lived in the south half which represented the earth. Within each half of the village, individual clans were carefully located based on their member's tribal duties and relationship to other clans. Earth lodges were as large as 60 feet in diameter and might hold several families, even their horses. The woodland custom of these earth lodges was replaced with easier to build and more practical tipis. Tipis are basically tents covered in buffalo hides like those used by the Sioux. Tipis were also used during buffalo hunts away from the villages, and when relocating from one village area to another.

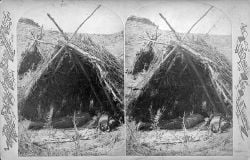

The Paiute, like other tribes of the Great Basin area, lived in domed, round shelters known as Wickiups or Kahn by the Kaibab Paiute. The curved surfaces made them ideal shelters for all kinds of conditions; an escape from the sun during summer, and when lined with bark they were as safe and warm as the best houses of early colonists in winter. The structures were formed with a frame of arched poles, most often wooden, which are covered with some sort of roofing material. Details of construction varied with the local availability of materials, but generally included grass, brush, bark, rushes, mats, reeds, hides, or cloth. They built these dwellings in different locations as they moved throughout their territory. Since all their daily activities took place outside, including making fires for cooking or warmth, the shelters were primarily used for sleeping.

An igloo, translated sometimes as "snowhouse," is a shelter constructed from blocks of snow, generally in the form of a dome. Although iglooit are usually associated with all Inuit, they were predominantly constructed by people of Canada's Central Arctic and Greenlands Thule area. Other Inuit people tended to use snow to insulate their houses which consisted of whalebone and hides. The use of snow is due to the fact that snow is an insulator (due to its low density). On the outside, temperatures may be as low as -45 °C (-49 °F), but on the inside the temperature may range from -7 °C (19 °F) to 16 °C (61 °F) when warmed by body heat alone.[14]

Religion

Native American spirituality includes a number of stories and legends that are mythological. Many Native Americans would describe their religious practices as a form of spirituality, rather than religion, although in practice the terms may sometimes be used interchangeably. Shamanism was practiced among many tribes. Common spirituality focused on the maintenance of a harmonious relationship with the spirit world, and often consisted of worshiping several lesser spirits and one great creator. This was often achieved by ceremonial acts, usually incorporating sandpainting. The colors—made from sand, charcoal, cornmeal, and pollen—depicted specific spirits. These vivid, intricate, and colorful sand creations were erased at the end of the ceremony.

Some tribes in the prairie regions of the United States and Canada permanent structures that were apparently used for religious purposes. These medicine wheels, or "sacred hoops," were constructed by laying stones in a particular pattern on the ground. Most medicine wheels resemble a wagon wheel, having a center cairn of stones surrounded by an outer ring of stones, and then "spokes," or lines of rocks, coming out from the cairn. The outer rings could be large, reaching diameters of as much as 75 feet.

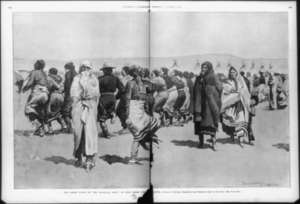

One of the most famous religious rituals was known as the Ghost Dance, which was a religious movement that began in 1889 and was readily incorporated into numerous Native American belief systems. At the core of the movement was the visionary Indian leader Jack Wilson, known as Wovoka among the Paiute. Wovoka prophesied an end to white American expansion while preaching messages of clean living, an honest life, and peace between whites and Indians. First performed in accordance with Wilson's teachings among the Nevada Paiute, the Ghost Dance is built on the foundation of the traditional circle dance. The practice swept throughout much of the American West, quickly reaching areas of California and Oklahoma. As it spread from its original source, Native American tribes synthesized selective aspects of the ritual with their own beliefs, creating changes in both the society that integrated it and the ritual itself.

The Ghost Dance took on a more militant character among the Lakota Sioux who were suffering under the disastrous U.S. government policy that had sub-divided their original reservation land and forced them to turn to agriculture. By performing the Ghost Dance, the Lakota believed they could take on a "Ghost Shirt" capable of repelling the white man's bullets. Seeing the Ghost Dance as a threat and seeking to suppress it, U.S. Government Indian agents initiated actions that tragically culminated with the death of Sitting Bull and the later Wounded Knee massacre. The Ghost Dance and its ideals as taught by Wokova soon began to lose energy and it faded from the scene, although it was still practiced by some tribes into the twentieth century.

The Longhouse Religion refers to the religious movement in indigenous peoples who formerly lived in longhouses. Prior to the adoption of the single family dwelling, various groups of peoples lived in large, extended family homes also known as long houses. During inclement weather these homes served as meeting places, town halls, and theater. The religious movement known as Handsome Lake cult or Gai'wiio (Good Message in Seneca) was started by the Seneca Chief Handsome Lake (Ganioda'yo) who designated the long house structure as their place of worship. Founded in 1799, it is the oldest active prophet movement in North America. At the age of 64, after a lifetime of poverty and alcoholism, Ganioda'yo received his revelations while in a trance, after which he formed the movement. While it has similarities to the Quakers in practice, this new Seneca religion contained elements from both Christianity and traditional beliefs. Ganioda'yo's teachings spread through the populations of western New York, Pennsylvania, and Iroquois country, eventually being known as The Code of Handsome Lake. The movement is currently practiced by about five thousand people.

The most widespread religion at the present time is known as the Native American Church. It is a syncretistic church incorporating elements of native spiritual practice from a number of different tribes as well as symbolic elements from Christianity. Its main rite is the peyote ceremony. Quanah Parker of the Comanche is credited as the founder of the Native American Church Movement, which started in the 1890s and was formally incorporated in 1918. Parker adopted the peyote religion after reportedly seeing a vision of Jesus Christ when given peyote by a Ute medicine man to cure the infections of his wounds following a battle with Federal Troops. Parker taught that the Sacred Peyote Medicine was the Sacrament given to all Peoples by the Creator, and was to be used with water when taking communion in some Native American Church medicine ceremonies. The Native American Church was the first truly "American" religion based on Christianity outside of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In the American Southwest, especially New Mexico, a syncretism between the Catholicism brought by Spanish missionaries and the native religion is common; the religious drums, chants, and dances of the Pueblo people are regularly part of Masses at Santa Fe's Saint Francis Cathedral.[15] Native American-Catholic syncretism is also found elsewhere in the United States. (for example, the National Kateri Tekakwitha Shrine in Fonda, New York and the National Shrine of the North American Martyrs in Auriesville, New York).

Gender roles

Most Native American tribes had traditional gender roles. In some tribes, such as the Iroquois nation, social, and clan relationships were matrilineal and/or matriarchal, although several different systems were in use. One example is the Cherokee custom of wives owning the family property. Men hunted, traded, and made war, while women cared for the young and the elderly, fashioned clothing and instruments, and cured meat. The cradle board was used by mothers to carry their baby while working or traveling. However, in some (but not all) tribes a kind of transgender was permitted, known as the Two-Spirit person.

Apart from making home, women had many tasks that were essential for the survival of the tribes. They made weapons and tools, took care of the roofs of their homes and often helped their men hunt buffalo.[16] In some of these tribes girls were also encouraged to learn to ride and fight. Though fighting was mostly left to the boys and men, there had been cases of women fighting alongside them, especially when the existence of the tribe was threatened.[17]

Music and art

Native American music is almost entirely monophonic, but there are notable exceptions. Traditional Native American music often includes drumming and/or the playing of rattles or other percussion instruments but little other instrumentation. Flutes and whistles made of wood, cane, or bone are also played, generally by individuals, but in former times also by large ensembles (as noted by Spanish conquistador de Soto). The tuning of these flutes is not precise and depends on the length of the wood used and the hand span of the intended player, but the finger holes are most often around a whole step apart and, at least in Northern California, a flute was not used if it turned out to have an interval close to a half step.

The most widely practiced public musical form among Native Americans in the United States is that of the pow-wow. At pow-wows, such as the annual Gathering of Nations in Albuquerque, New Mexico, members of drum groups sit in a circle around a large drum. Drum groups play in unison while they sing in a native language and dancers in colorful regalia dance clockwise around the drum groups in the center. Familiar pow-wow songs include honor songs, intertribal songs, crow-hops, sneak-up songs, grass-dances, two-steps, welcome songs, going-home songs, and war songs. Most indigenous communities in the United States also maintain traditional songs and ceremonies, some of which are shared and practiced exclusively within the community.[18]

Performers with Native American parentage have occasionally appeared in American popular music, such as Rita Coolidge, Wayne Newton, Gene Clark, Tori Amos, and Redbone (band). Some, such as John Trudell have used music to comment on life in Native America, and others, such as R. Carlos Nakai integrate traditional sounds with modern sounds in instrumental recordings. A variety of small and medium-sized recording companies offer an abundance of music by Native American performers young and old, ranging from pow-wow drum music to hard-driving rock-and-roll and rap.

Native American art comprises a major category in the world art collection. Native American contributions include pottery, paintings, jewelry, weaving, sculpture, basketry, and carving. The Pueblo peoples crafted impressive items associated with their religious ceremonies. Kachina dancers wore elaborately painted and decorated masks as they ritually impersonated various ancestral spirits. Sculpture was not highly developed, but carved stone and wood fetishes were made for religious use. Superior weaving, embroidered decorations, and rich dyes characterized the textile arts. Both turquoise and shell jewelry were created, as were high-quality pottery and formalized pictorial arts.

Many American Indian tribes prided themselves on the spiritual carvings known as totem poles, which are monumental sculptures carved from great trees, typically Western Redcedar, by a number of Indigenous cultures along the Pacific Northwest coast of North America. The word "totem" is derived from the Ojibwe word odoodem, "his totem, his kinship group" (root -oode). The fur trade gave rise to a tremendous accumulation of wealth among the coastal peoples, and much of this wealth was spent and distributed in lavish potlatches frequently associated with the construction and erection of totem poles. Poles were commissioned by many wealthy leaders to represent their social status and the importance of their families and clans.

The beginning of totem pole construction started in North America. Being made of wood, they decay easily in the rain forest environment of the Northwest Coast, so no examples of poles carved before 1800 exist. However eighteenth century accounts of European explorers along the coast indicate that poles certainly existed at that time, although small and few in number. In all likelihood, the freestanding poles seen by the first European explorers were preceded by a long history of monumental carving, particularly interior house posts. Early twentieth-century theories, such as those of the anthropologist Marius Barbeau who considered the poles an entirely post-contact phenomenon made possible by the introduction of metal tools, were treated with skepticism at the time and are now discredited.

Traditional economy

As these native peoples encountered European explorers and settlers and engaged in trade, they exchanged food, crafts, and furs for trinkets, glass beads, blankets, iron, and steel implements, horses, firearms, and alcoholic beverages. Many and most of the American Indians were hunter-gatherers, and as such, relied heavily on the barter system rather than cash money. Over time however, many became reliant on their ability to produce arts and crafts, and highly decorative weapons in order to sustain themselves in matters of commerce with the white people.

A ceremonial feast called a potlatch, practiced among a diverse group of Northwest Coast Indians as an integral part of indigenous culture, had numerous social implications. The Kwakiutl, of the Canadian Pacific Northwest, are the main group that still practices the potlatch custom. Although there were variants in the external form of the ceremony as conducted by each tribe, the general form was that of a feast in which gifts were distributed. The size of the gathering reflected the social status of the host, and the nature of the gifts given depended on the status of the recipients. Potlatches were generally held to commemorate significant events in the life of the host, such as marriage, birth of a child, death, or the assumption of a new social position. Potlatches could also be conducted for apparently trivial reasons, because the true reason was to validate the host's social status. Such ceremonies, while reduced to external materialistic form in Western society, are important in maintaining stable social relationships as well as celebrating significant life events. Fortunately, through studies by anthropologists, the understanding and practice of such customs has not been lost.

Contemporary

There are 561 federally recognized tribal governments in the United States. These tribes possess the right to form their own government, to enforce laws (both civil and criminal), to tax, to establish membership, to license and regulate activities, to zone and to exclude persons from tribal territories. Limitations on tribal powers of self-government include the same limitations applicable to states; for example, neither tribes nor states have the power to declare war, engage in foreign relations, or coin money (this includes paper currency).

The largest tribes in the U.S. by population are Navajo, Cherokee, Choctaw, Sioux, Chippewa, Apache, Lumbee, Blackfeet, Iroquois, and Pueblo. The majority of Americans with Native American ancestry are of mixed blood.

In addition, there are a number of tribes that are recognized by individual states, but not by the federal government. The rights and benefits associated with state recognition vary from state to state.

Some tribal nations have been unable to establish their heritage and obtain federal recognition. The Muwekma Ohlone of the San Francisco bay area are pursing litigation in the federal court system to establish recognition.[19] Many of the smaller eastern tribes have been trying to gain official recognition of their tribal status. The recognition confers some benefits, including the right to label arts and crafts as Native American and permission to apply for grants that are specifically reserved for Native Americans. But gaining recognition as a tribe is extremely difficult; to be established as a tribal group, members have to submit extensive genealogical proof of tribal descent.

Military defeat, cultural pressure, confinement on reservations, forced cultural assimilation, outlawing of native languages and culture, termination policies of the 1950s and 1960s and earlier, slavery, and poverty have had deleterious effects on Native Americans' mental and physical health. Contemporary health problems suffered disproportionately include alcoholism, heart disease, and diabetes.

As recently as the 1970s, the Bureau of Indian Affairs was still actively pursuing a policy of "assimilation," dating at least to the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924.[20] The goal of assimilation — plainly stated early on — was to eliminate the reservations and steer Native Americans into mainstream U.S. culture. Forced relocations continued into the twenty-first century to gain access to coal and uranium contained in Native American land .[21]

Gambling has become a leading industry. Casinos operated by many Native American governments in the United States are creating a stream of gambling revenue that some communities are beginning to use as leverage to build diversified economies. Native American communities have waged and prevailed in legal battles to assure recognition of rights to self-determination and to use of natural resources. Some of those rights, known as treaty rights are enumerated in early treaties signed with the young United States government. Tribal sovereignty has become a cornerstone of American jurisprudence, and at least on the surface, in national legislative policies. Although many Native American tribes have casinos, they are a source of conflict. Most tribes, especially small ones such as the Winnemem Wintu of Redding, California, feel that casinos and their proceeds destroy culture from the inside out. These tribes refuse to participate in the gaming industry.

Native Americans are the only known ethnic group in the United States requiring a federal permit to practice their religion. The Eagle Feather Law, (Title 50 Part 22 of the Code of Federal Regulations), stipulates that only individuals of certifiable Native American ancestry enrolled in a federally recognized tribe are legally authorized to obtain eagle feathers for religious or spiritual use. Native Americans and non-Native Americans frequently contest the value and validity of the eagle feather law, charging that the law is laden with discriminatory racial preferences and infringes on tribal sovereignty. The law does not allow Native Americans to give eagle feathers to non-Native Americans, a common modern and traditional practice. Many non-Native Americans have been adopted into Native American families, made tribal members, and given eagle feathers.

In the early twenty-first century, Native American communities remain an enduring fixture on the United States landscape, in the American economy, and in the lives of Native Americans. Communities have consistently formed governments that administer services like firefighting, natural resource management, and law enforcement. Most Native American communities have established court systems to adjudicate matters related to local ordinances, and most also look to various forms of moral and social authority vested in traditional affiliations within the community. To address the housing needs of Native Americans, Congress passed the Native American Housing and Self Determination Act (NAHASDA) in 1996. This legislation replaced public housing, and other 1937 Housing Act programs directed towards Indian Housing Authorities, with a block grant program directed towards Tribes.

Notes

- ↑ Profiles of General Demographic Characteristics 2000: 2000 Census of Population and Housing. U.S. Census Bureau, May, 2001.

- ↑ "In combination with one or more of the other races listed." Figure here derived by subtracting figure for "One race (American Indian and Alaska Native)": 2,475,956, from figure for "Race alone or in combination with one or more other races (American Indian and Alaska Native)": 4,119,301, giving the result 1,643,345. Other races counted in the census include: "White"; "Black or African American"; "Asian"; "Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander"; and "Some other race."

- ↑ Dennis Gaffney, "American Indian" or "Native American"? Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ↑ American Indian vs. Native American: A note on terminology Octoroon. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ↑ Fernando Luna Calderón, DNA in the Dominican Republic Journal of Caribbean Amerindian History and Anthropology (2002). Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ↑ Jay F. Kirkpatrick and Patricia M. Fazio, The Surprising History of America's Wild Horses Live Science, July 24, 2008. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ↑ Smallpox epidemic ravages Native Americans on the northwest coast of North America in the 1770s HistoryLink.org. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ↑ Paul Schneider, Brutal Journey: The Epic Story of the First Crossing of North America (Henry Holt and Company, 2006), 70–71.

- ↑ Four Indian Kings National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ↑ James W. Duncan, An Act to Prevent Amalgamation with Colored Persons Mixed Race Studies. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ↑ J.B. Davis, "Slavery in the Cherokee Nation" Chronicles of Oklahoma 11(4) (December, 1933).

- ↑ Ron Soodalter, Massacre & Retribution: The 1779-80 Sullivan Expedition HistoryNet. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ↑ Wilcomb E. Washburn, Indians and the American Revolution AmericanRevolution.org. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ↑ Rich Holihan, Dan Keeley, Daniel Lee, Powen Tu and Eric Yang, How Warm is an Igloo? Cornell University Library. BEE453 (Spring 2003). Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ↑ Jay Fikes, A Brief History of the Native American Church Entheology.com. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ↑ Native American Women Indians.org. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ↑ Sara Kettler, Native American Heritage Month: Celebrating the Original Women of the Americas Biography.com, November 7, 2017. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ↑ John Bierhosrt, A Cry from the Earth: Music of North American Indians (Ancient City Press, 1992, ISBN 978-0941270533).

- ↑ The Muwekman Ohlone Tribe of San Francisco, California Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ↑ The Allotment and Assimilation Era (1887 - 1934) Howard University Law Library. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ↑ Brigitte Thimiakis, The Genocide and Relocation of the Dine'h (Navajo) Senaa. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adams, David Wallace. Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience 1875–1928, University Press of Kansas, 1975. ISBN 0700608389

- Bierhorst, John. A Cry from the Earth: Music of North American Indians. Ancient City Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0941270533

- Calloway, Colin G. The American Revolution in Indian Country: Crisis and Diversity in Native American Communities. Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 0521475694

- Davis, Mary B., Joan Berman, Mary E. Graham, and Lisa A. Mitten (eds.). Native America in the Twentieth Century: An Encyclopedia. Garland Publishing, 1996. ISBN 978-0815325833

- Deloria, Vine. Custer Died for Your Sins: An Indian Manifesto. New York, NY: Macmillan, 1988. ISBN 978-0806121291

- Downes, Randolph C. Council Fires on the Upper Ohio: A Narrative of Indian Affairs in the Upper Ohio Valley until 1795. University of Pittsburgh Press, 1940.

- Graymont, Barbara. The Iroquois in the American Revolution. Syracuse University Press, 1975. ISBN 0815601166

- Hirschfelder, Arlene B., Mary G. Byler, and Michael Dorris. Guide to research on North American Indians. American Library Association, 1983. ISBN 0838903533

- Jones, Peter N. Respect for the Ancestors: American Indian Cultural Affiliation in the American West. Boulder, CO: Bauu Press, 2005. ISBN 0972134921

- Krech, Shepard. The Ecological Indian : Myth and History. W.W. Norton, 1999. ISBN 0393047555

- Nichols, Roger L. Indians in the United States & Canada, A Comparative History. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1998. ISBN 0803283776

- Nies, Judith. Native American History: A Chronology of a Culture's Vast Achievements and Their Links to World Events. Ballantine Books, 1996. ISBN 978-0345393500

- O’Donnell, James. Southern Indians in the American Revolution. University of Tennessee Press, 1973. ISBN 0870491318

- Pohl, Frances K. Framing America: A Social History of American Art. New York, NY: Thames & Hudson, 2002. ISBN 978-0500283349

- Pritzker, Barry M. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0195138771

- Schneider, Paul. Brutal Journey: the epic story of the first crossing of North America. Henry Holt and Company, 2006. ISBN 080506835X

- Singer, Joseph William. Property Law: Rules, Policies, Practices. Aspen Publishers, 2006. ISBN 978-0735555471

- Sletcher, Michael. "North American Indians," in Will Kaufman and Heidi Macpherson, eds., Britain and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History. 2 vols., Oxford, 2005. ISBN 978-1851094318

- Snipp, C.M. American Indians: The First of this Land. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation, 1991. ISBN 978-0871548238

- Sturtevant, William C. (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1978–present.

- Tiller, Veronica E. (ed.) Discover Indian Reservations USA: A Visitors' Welcome Guide. Foreword by Ben Nighthorse Campbell. Denver, CO: Council Publications, 1992. ISBN 0963258001

- Waldman, Carl. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. Checkmark Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0816062744

- Wilson, James. The Earth Shall Weep: A History of Native America. Grove Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0802136800

External Links

All links retrieved November 11, 2022.

- Comanche Lodge

- American Indian Studies California State University, Long Beach

- American Indians of the Pacific Northwest

- McKenney and Hall Tribes of North America University of Washington Libraries.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.