Choctaw

| Choctaw |

|---|

| Oklahoma Choctaw Battalion Flag during the American Civil War |

| Total population |

| 160,000 |

| Regions with significant populations |

(Oklahoma, Mississippi, Louisiana, Alabama) |

| Languages |

| English, Choctaw |

| Religions |

| Mainly Protestantism |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Five Civilized Tribes other Native American groups |

The Choctaws, or Chahtas, are a Native American people originally from the Southeastern United States (Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana) of the Muskogean linguistic group. They were supportive of the Americans against the British, but were forcibly removed to Oklahoma, herded westward along the Trail of Tears. Those who survived, reorganized and established themselves in their new home. They became known as one of the "Five Civilized Tribes," because they had integrated numerous cultural and technological practices of their European American neighbors.

Choctaw are remembered for their generosity in providing humanitarian relief during the Irish Potato Famine decades before the Red Cross was created. Choctaw also participated in World War I and World War II as code talkers. Contemporary Choctaw are of two distinct groups, the tribe (in Mississippi) and the nation (in Oklahoma), with additional bands settled in Alabama and Louisiana.

History

Antoine du Pratz, in his Historie de La Louisiane (Paris, 1758) recounted that "when I asked them from whence the Chat-kas came, to express the suddenness of their appearance they replied that they had come out from under the earth." Despite an authorial assumption that this story was intended to "express the suddenness of their appearance" and not a literal creation story, this is perhaps the first European writing to contain the seed of the story. Bernard Romans' 1771 account (Natural History of East and West Florida. New York, 1775) reiterated the story:

These people are the only nation from whom I could learn any idea of a traditional account of a first origin; and that is their coming out of a hole in the ground, which they shew between their nation and the Chickasaws; they tell us also that their neighbors were surprised at seeing a people rise at once out of the earth. [1]

As told by both early nineteenth century as well as contemporary Mississippi Choctaw storytellers, it was either Nanih Waiya or a cave nearby from which the Choctaw people emerged. Another story (Catlin's Smithsonian Report, 1885) linking the Choctaw people to Nanih Waiya explains that the Choctaw were originally inhabitants of a place far to the west:

The Choctaws, a great many winters ago, commenced moving from the country where they then lived, which was a great distance to the west of the great river and the mountains of snow, and they were a great many years on their way. A great medicine man led them the whole way, by going before with a red pole, which he stuck in the ground every night where they encamped. This pole was every morning found leaning to the east, and he told them that they must continue to travel to the east until the pole would stand upright in their encampment, and that there the Great Spirit had directed that they should live.

According to the story, it was at Nanih Waiya that the pole finally stood straight. (Nanih Waiya means "leaning hill" in Choctaw.) Nanih Waiya is in Neshoba County, Mississippi about ten miles southeast of Noxapater. Previously a State Park, it has now been returned to the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians.

Patricia Galloway argued from fragmentary archaeological and cartographic evidence that the Choctaw did not exist as a unified people before the seventeenth century, and only at that time did various southeastern peoples (remnants of Moundville, Plaquemine, and other Mississippian cultures) coalesce to form a self-consciously Choctaw people.[2] Regardless of the time frame, however, the homeland of the Choctaw or of the peoples from whom the Choctaw nation arose includes Nanih Waiya. The mound and the surrounding area are sacred ground to Choctaws, and are a central point of connection between the Choctaws and their homeland.

European contact

The Choctaw were no doubt a part of the Mississippian culture in the Mississippi River valley. At the time that the Spanish made their first forays into the gulf shores, the political centers of the Mississippians were already in decline or gone. The region is best described as a collection of moderately-sized native chiefdoms (such as the Coosa chiefdom on the Coosa River) interspersed with completely autonomous villages and tribal groups. This is what the earliest Spanish explorers encountered, beginning in 1519. Choctaws regularly traveled hundreds of miles from their homes for long periods of time. They set out early in the fall and returned to their reserved lands at the opening of spring to plant their gardens. At that time they encountered the Europeans.

In 1528, Pánfilo de Narváez traveled through what was likely the Mobile Bay area, encountering American Indians who fled and burned their towns in response to the Spaniard’s approach. This response was a prelude to Hernando de Soto’s extensive journeys in 1540 to 1543. De Soto traveled up through Florida, and then down into the Alabama-Mississippi area that later was inhabited by the Choctaw. Reading between the lines of his accounts of Native interactions provides a region full of tribes of various sizes and with various degrees of control over neighboring areas.

De Soto had the most well equipped army at the time. His successes were well-known throughout Spain, and many people from all backgrounds joined his quest for untold riches to be plundered in the New World. However, the brutalities of the De Soto expedition were known by the Choctaw, so they decided to aggressively defend their country. Bob Ferguson noted:

Hernando de soto, leading his well-equipped Spanish fortune hunters, made contact with the Choctaws in the year 1540. He had been one of a triumvirate which wrecked and plundered the Inca empire and, as a result, was one of the wealthiest men of his time. His invading army lacked nothing in equipage. In true conquistador style, he took as hostage a chief named Tuscaloosa (Black Warrior), demanding of him carriers and women. The carriers he got at once. The women, Tuscaloosa said, would be waiting in Mabila (Mobile). The chief neglected to mention that he had also summoned his warriors to be waiting in Mabila. On October 18, 1540, DeSoto entered the town and received a gracious welcome. The Choctaws feasted with him, danced for him, then attacked him.[3]

The Battle of Mabila was a turning point for the De Soto venture; the battle "broke the back" of the campaign, and they never fully recovered.

The impact of European diseases on the Choctaw is unclear. Reports of De Soto’s journeys do not describe illness among his men, although pigs traveling with them often escaped and may have been excellent vectors for dangerous microbes. The two subsequent brief forays into the Southeast by Tristán de Luna y Aellano in 1559 and Juan Pardo in 1565-1567 do not provide any evidence for widespread epidemics. After Pardo, the historical picture ends. There would be no official European contact in the area at all for more than a century, when in 1699, Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville recorded his experience with a Choctaw.

During that time the group identities of the region completely transformed. Illegal fur trading may have led to unofficial contact between the British settlers through tribes such as the Creek and Chickasaw, but unfortunately, the archaeological record for this period between 1567 and 1699 is not complete or well-studied. There are, however, similarities in pottery coloring and burials that suggest the following scenario for the emergence of the distinctive Choctaw culture: the Choctaw region (generally located between the Natchez bluffs to the south and the Yazoo basin to the north) was slowly occupied by Burial Urn people from the Bottle Creek area in the Mobile delta, along with remnants of the Moundville chiefdom that had collapsed some years before. Facing severe depopulation, they fled westward, where they combined with the Plaquemine and a group of “prairie people” living near the area. When precisely this occurred is not entirely clear, but in the space of several generations, a new culture had been born (albeit with a strong Mississippian background).

United States Relations

During the American Revolutionary War, Choctaws divided over whether to support Britain or Spain (who declared war on Britain in 1779) with most Choctaw warriors who fought in the Revolutionary War supported the newly formed United States of America. Ferguson states in "1775 The American Revolution began a period of new alignments for the Choctaws and other southern Indians. Choctaw scouts served under Washington, Morgan, Wayne and Sullivan." After the Revolutionary War, the Choctaws were reluctant to ally themselves with countries hostile to the U.S. John R. Swanton wrote:

The Choctaw were never at war with the Americans. A few were induced by Tecumseh to ally themselves with the hostile Creeks, but the Nation as a whole was kept out of anti-American alliances by the influences of Apushmataha, greatest of all Choctaw chiefs.[4]

Ferguson also writes that in "1783 [was the] end of American Revolution. Franchimastabe, Choctaw head chief, went to Savannah, Georgia to secure American trade." Some Choctaw scouts served with U.S. General Anthony Wayne in the Northwest Indian War. During the American Civil War, the Choctaws sided with the southern states. Major S. G. Spann, Commander of Dabney H. Maury Camp No. 1312, U.C.V., Meridian, Mississippi, wrote:

Many earnest friends and comrades insist that the Choctaw Indian as a Confederate soldier should receive his proper place on the scroll of events during the War between the States. This task having been so nearly ignored, I send some reminiscences that will be an exponent of the extraordinary merit of the Choctaw Indian on the American Continent. My connection with the Choctaw Indians was brought about incidentally: Major J.W. Pearce, of Hazelhurst, Mississippi, organized a battalion of Choctaw Indians, of Kemper, DeKalb, Neshoba, Jasper, Scott, and Newton Counties, Mississipi, known as "First Battalion of Choctaw Indians, Confederate army."

George Washington’s Indian policy was used to “civilize” Indians. He believed that Indians were equals, but believed their society was inferior. His six-point plan included: impartial justice toward Indians, regulated buying of Indian lands, promotion of commerce, promotion of experiments to 'civilize' or improve Indian society, presidential authority to give “presents,” and providing punishments to those who violated Indian rights.

Removal and treaties

Although there were many treaties with other European nations, only nine treaties were signed between the Choctaws and the United States between the years of 1786 and 1830. Ferguson writes, "nine treaties were signed during a forty-four-year period, from 1786 to 1830. I shall stress the amounts of Choctaw land involved in these treaties, even though they included agreements relating to other matters, because land was the Indians' most valuable resource."

The last treaty, the most significant, was the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek (1830). The treaty signed away the remaining traditional homeland of the Choctaw to the United States. Article 14 of that treaty allowed for some Choctaws to remain in the state of Mississippi:

Each Choctaw head of a family being desirous to remain and become a citizen of the States, shall be permitted to do so, by signifying his intention to the Agent within six months from the ratification of this Treaty, and he or she shall thereupon be entitled to a reservation of one section of six hundred and forty acres of land, to be bounded by sectional lines of survey; in like manner shall be entitled to one half that quantity for each unmarried child which is living with him over ten years of age; and a quarter section to such child as may be under 10 years of age, to adjoin the location of the parent. If they reside upon said lands intending to become citizens of the States for five years after the ratification of this Treaty, in that case a grant in fee simple shall issue; said reservation shall include the present improvement of the head of the family, or a portion of it. Persons who claim under this article shall not lose the privilege of a Choctaw citizen, but if they ever remove are not to be entitled to any portion of the Choctaw annuity.

The Choctaw would become the first of the "Five Civilized Tribes" to be removed from the southeastern United States, as the federal and state government desired Indian lands to accommodate a growing agrarian Anglo society. Along with the Creek, Cherokee, Chickasaw, and Seminole, the Choctaw attempted to resurrect their traditional lifestyle and government in their new homeland.

Those Choctaws who were "forcibly removed" to the Indian territory between 1831 and 1838 were organized as the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. Those who signed under article 14 of the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek later formed the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. In 1831, tens of thousands of Choctaw walked the 800km journey to Oklahoma and many died. The removals continued until the early twentieth century. Ferguson states, "1903 MISS: Three-hundred Mississippi Choctaws were persuaded to remove to the Nation [in Oklahoma]." The removals became known as the "Trail of Tears."

Irish Potato Famine aid

In 1847, midway through the Irish Potato Famine, a group of Choctaws collected $170 (although many articles say the original amount was $710 after a misprint in Angi Debo's "The Rise and Fall of the Choctaw Nation") and sent it to help starving Irish men, women, and children. "It had been just 16 years since the Choctaw people had experienced the Trail of Tears, and they had faced starvation… It was an amazing gesture. By today's standards, it might be a million dollars" noted Judy Allen, editor of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma's newspaper, Bishinik, based at the Oklahoma Choctaw tribal headquarters in Durant, Oklahoma. To mark the 150th anniversary, eight Irish people retraced the Trail of Tears.[5]

World War I code talkers

In World War I, a group of Choctaws serving in the U.S. Army used their native language as a code. With at least one Choctaw man placed in each field company headquarters, they handled military communications by field telephone, translated radio messages into the Choctaw language, and wrote field orders to be carried by "runners" between the various companies. The German army, which captured about one out of four messengers, never deciphered the messages written in Choctaw. These Choctaws were the forerunner to Native Americans from various nations, most notably the Navajo, who were used as radio operators, or code talkers, during World War II.

The Code Talker Recognition Act (HR 4597 and S 1035) recognized these veterans who were often until recently ignored for their service performed for the United States.[6]

Culture

The Choctaws were known for their rapid incorporation of European modernity. John R. Swanton wrote,

It is generally testified that the Creeks and Seminole, who had the most highly developed native institutions, were the slowest to become assimilated into the new political and social organism which was introduced from Europe. The Chickasaw come next and the Cherokee and Choctaw adapted themselves most rapidly of all.[4]

Language

The Choctaw language is a member of the Muskogean family. The language was well known among the frontiersmen of the early 1800s. The language is closely related to Chickasaw and some linguists consider the two dialects of a single language.

Early religion

The Choctaws believed in a good spirit and an evil spirit, and they may have been sun worshippers. Swanton wrote,

the Choctaws anciently regarded the sun as a deity … the sun was ascribed the power of life and death. He was represented as looking down upon the earth, and as long as he kept his flaming eye fixed on any one, the person was safe … fire, as the most striking representation of the sun, was considered as possessing intelligence, and as acting in concert with the sun … [having] constant intercourse with the sun.[4]

Prayers may have been introduced by missionaries; however, Choctaw prophets were known to address the sun: an old Choctaw informed Wright that, before the arrival of the missionaries, they had no conception of prayer. However, he adds, 'I have indeed heard it asserted by some, that anciently their hopaii, or prophets, on some occasions were accustomed to address the sun.[4]

The evil spirit, or Na-lusa-chi-to (black being/soul eater), sought to harm people. It may appear, as told in stories, in the form of a shadow person.

Crimes

Murder was usually dealt with by revenge. Swanton writes,

Murder, i.e., intratribal man-killing, could be atoned for ordinarily only by the death of the murderer himself or some substitute acceptable to the injured family… they cherish a desire for revenge for a generation.[4]

Stolen property was usually punishable by returning the stolen goods or other compensation. Swanton says, "thieves apprehended with the stolen property in their possession were forced to return it. If they could not produce the property, either they or their families were compelled to return goods of equal value."[4] Theft was later punishable by a whip. Swanton states of Cushman, "for minor offenses, whipping was the punishment; fifty lashes for the first offense, one hundred for the second, and death by the rifle for the third offense … (1899)."[4]

Incest was considered a crime: "incest … was anciently a major crime, but we have no record of the punishments inflicted on account of it."[4]

Warfare

Choctaw warfare had many associated customs. Before war was declared a council was held to discuss the matter, which would last about eight days. Swanton writes on Bossu's account:

The Choctaws love war and have some good methods of making it. They never fight standing fixedly in one place; they flit about; they heap contempt upon their enemies without at the same time being braggarts, for when they come to grips they fight with much coolness.[4]

Superstition was a part of Choctaw warfare:

The Choctaws are extremely superstitious. When they are about to go to war they consult their Manitou, which is carried by the chief. They always exhibit it on that side where they are going to march toward the enemy, the warriors standing guard about.[4]

When the Choctaw captured an enemy, he or she was displayed as a war trophy:

They never exercised so much cruelty upon their captive enemies as the other savages; they almost always brought them home to shew them, and then dispatched them with a bullet or hatchet; after which, the body being cut into many parts, and all the hairy pieces of skin converted into scalps, the remainder is buried and the above trophies carried home, where the women dance with them till tired; then they are exposed on the tops of the hot houses till they are annihilated.[4]

For some societies, the practice of decapitation was considered an honor; a fallen Choctaw warrior's head was brought back after a battle. This practice seems to be true for the Choctaw of Oskelagna. Swanton says of De Lusser (1730):

There was one who brought the head of one of their people who had been killed. He threw it at my feet telling me that he was a warrior who had lost his life for the French and that it was well to weep for his death.[4]

They also had ceremonies for peace in which they named, adopted, smoked, and performed dances. One such dance was the eagle tail dance. The Bald Eagle, who was seen as having direct contact with the upper world of the sun, was regarded as a symbol of peace. Choctaw women painted in white would adopt and name representatives of the former enemy as kin. Smoking sealed agreements between peoples and sanctified peace between the two nations.[7]

Mythology

The Choctaw have many stories about little people:

the Choctaws in Mississippi say that there is a little man, about two feet high, that dwells in the thick woods and is solitary in his habits … he often playfully throws sticks and stones at the people … the Indian's doctors say that Bohpoli [thrower] assists them in the manufacture of their medicines.[4]

The little people are said to take young children to the forest to teach them how to be medicine men.

Stories

Storytelling is a popular part of entertainment in many Native American societies. This stood also true for the Choctaws. Stories would recount their origins and would retell the deeds of heroes long gone. There are also stories about possums, raccoons, turtles, birds, chipmunks, and wolves:

The Choctaw believed that their people came forth from the sacred mound of Nanih Waiya. In relation to this creation myth is the legend of the Choctaw tribe's migration under the leadership of Chata. Several versions of their creation and migration legends have been perpetuated by the Native Americans and remain very popular among contemporary Choctaws, especially the elderly. The young, however, have a more active interest in the mischievous deed of various forest animals or in stories about the creation of the wild forests.[8]

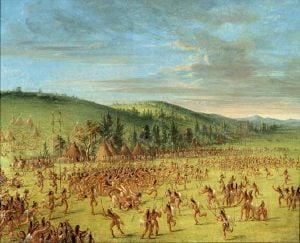

Stickball

Native American stickball, the oldest field sport in America, was also know as the "little brother of war" because of its roughness and substitution for war. When disputes arouse between Choctaw communities, stickball provided a "civilized" way to settle the issue. The earliest reference to stickball was in 1729 by a Jesuit priest.

The stickball games would involve as few as twenty or as many as 300 players, and even more people watching:

It is no uncommon occurrence for six or eight hundred or a thousand of these young men to engage in a game of ball, with five or six times that number of spectators, of men, women, and children, surrounding the ground, and looking on.[4]

The goal posts could be from a few hundred feet apart to a few miles. Goal posts were sometimes located within each opposing team's village.

The nature of the playing field was never strictly defined. The only boundaries were the two goalposts at either end of the playing area and these could be anywhere from 100 feet to five miles apart, as was the case in one game in the nineteenth century. (Kendall Blanchard, The Mississippi Choctaws at Play: The Serious Side of Leisure)

Stickball continues to be played today. The Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians play stickball every year at the Choctaw Indian Fair near Philadelphia, Mississippi, with the game played on a modern day football field.

Contemporary Choctaw

Return of Nanih Waiya

After nearly two hundred years, Nanih Waiya was returned. Nanih Waiya was a state park of Mississippi until the Mississippi Legislature State Bill 2803 officially returned control to Choctaws in 2006. The return of the land was a grandiose political statement to the testament of Choctaw respect.

Alabama

The MOWA Choctaw Reservation is located on 300 acres in between the small southwestern Alabama communities of McIntosh, Mt. Vernon and Citronelle. Aside from the reservation, tribal citizens numbering around 3,600, live in 10 small settlements near the reservation community. They are led by elected Chief Wilford Taylor and are some of the descendants of those Choctaw people who refused removal at the time of the 1830 Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. Their annual cultural festival, which includes Choctaw social dancing, stickball games, Choctaw princess contest, and an inter-tribal pow-wow occurs on the third weekend of June each year on their reservation lands.

Mississippi

Old Choctaw country included dozens of towns like Lukfata, Koweh Chito, Oka Hullo, Pante, Osapa Chito, Oka Cooply, and Yanni Achukma located in and around Neshoba and Kemper counties in Mississippi. The oldest Choctaw settlement is located in Neshoba county. The bones of great warriors are buried there.

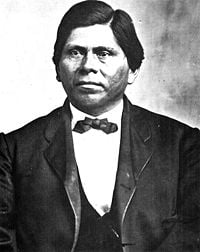

The Mississippi Choctaw Indian Reservation has eight communities: Bogue Chitto, Bogue Homa, Conehatta, Crystal Ridge, Pearl River, Red Water, Tucker, and Standing Pine. These communities are located in parts of nine counties throughout the state, although the largest concentration of land is in Neshoba County. The Choctaws still living in Mississippi make up the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, led by Chief Phillip Martin.

The Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians (MBCI) has one of the largest casinos located near Philadelphia, Mississippi, the Pearl River Resort.

Oklahoma

Most Choctaws were forcibly removed from Mississippi to Oklahoma during the 1830s. Choctaws contributed much to the early history of Oklahoma, even giving the state its name. Former Principal Chief Allen Wright suggested the name Oklahoma, from a contraction of the Choctaw words okla ("people") and humma ("red"). Oklahoma Choctaws comprise the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, established in the southeastern quadrant of the state. The capitol building, which was built in 1884, is located in Tushkahoma. Their elected Chief is Gregory E. Pyle, and the Nation's headquarters are located in Durant, Oklahoma, the nation's second largest city. McAlester is Choctaw Nation's largest city. Approximately 250,000 people live within the Choctaw Nation boundaries in Southeastern Oklahoma.

In 1959, the Choctaw Termination Act was passed. Unless repealed by the federal government, the Choctaw would effectively be terminated as a sovereign nation as of August 25, 1970. On August 24, 1970, just hours before it would become law, Richard Nixon signed a bill repealing the Termination Act of 1959. This close call prompted some Oklahoma Choctaw to spearhead a grassroots movement to change the direction of the tribal government.

In 1971, the Choctaw held their first popular election of a chief since Oklahoma entered the Union in 1907. Harry Belvin, who had been holding the position, was elected to a four year term as chief. In 1975, thirty-five year old David Gardner defeated Belvin to become the Choctaw Nation's second popularly elected chief. 1975 also marked the year that the United States Congress passed the landmark Indian Self-Determination and Education Act. This law revolutionized the relationship between Indian Nations and the federal government.

The Choctaw now had the power to negotiate and contract their own services, and have the power to determine what services were in the best interest of their own people. Under Gardner's term as chief, a tribal newspaper, Hello Choctaw was established. Discussions began on the issue of drafting and adopting a new constitution for the Choctaw people. A movement began to officially enroll more Choctaws, increase voter participation, and preserve the Choctaw language.

A new publication, the Bishinik, replaced Hello Choctaw in June 1978. Spirited debates over a proposed constitution divided the people, but in May 1979, a new constitution was adopted by the Choctaw nation. Faced with termination as a sovereign nation in 1970, the Choctaws emerged a decade later as a tribal government with a constitution, a popularly elected chief, a newspaper, and the prospects of an emerging economy and infrastructure that would serve as the basis for further empowerment and growth. The Oklahoma Choctaw today are a progressive and successful people, facing the twenty-first century with renewed hope and optimism.

Louisiana

The Jena Band of Choctaw Indians are located in LaSalle and Catahoula Parishes of Louisiana. After the relinquishment of the Louisiana Colony by France, members of the tribe began to move across the Mississippi River. By the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek in September of 1830 the main body of the Choctaw ceded all their land east of the Mississippi river. Choctaw migrated to the pine covered hills of what was then Catahoula Parish in Louisiana. Principle settlements were established on Trout Creek in LaSalle Parish and Bear Creek in Grant Parish.

The last traditional Chief died in 1968 and in 1974 the first tribal election of Tribal Chief was held. Subsequently the Jena Band of Choctaw Indians was officially recognized by the state of Louisiana as an Indian Tribe. The Jena Band of Choctaw Indians received federal recognition through the federal acknowledgment process in 1995. Tribal membership now totals 241.

The Jena Band of Choctaw Indians envisions the ideal future of The Jena Band of Choctaw Indians as being one in which "all Tribal members are both prosperous and contented in all aspects of their physical, emotional, economical, and spiritual well-being."[9]

Influential Choctaw leaders

- Tuscaloosa ("Dark Warrior") retaliated against Hernando de Soto at the Battle of Mabilia.

- Pushmataha (Apushmataha) was a Choctaw chief from 1764 to 1824. He negotiated treaties with the United States and fought on the American's side in the War of 1812. He is buried in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, DC.

- Greenwood LeFlore First Principal Chief of the Choctaw Nation.

- George W. Harkins was a Choctaw Chief during the removal era, and author of the “Farewell Letter to the American People”.

- Mosholatubbee was also a leader during the removal era.

- Hat-choo-tuck-nee ("The Snapping Turtle") (Peter Perkins Pitchlynn) was a highly influential leader during the removal era and after.

- Tulli was one of the greatest Choctaw stickball players.

- Josh Bolding, WWI Code Talker and War Hero.

- Muriel Wright, Choctaw Historian and Writer.

- Phillip Martin, chief of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians since 1979. Encouraged outside investment and reduced unemployment to nearly 0 percent on the reservation.

Notes

- ↑ Bernard Romans. Natural History of East and West Florida. (New York, 1775) A Concise History of East and West Florida, intro. By Rembert W. Patrick (Gainesville: Univ. of Florida Press, 1962)

- ↑ Patricia Galloway. Choctaw Genesis 1500-1700. (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1998)

- ↑ Bob Ferguson, Choctaw Chronology (1997)www.choctaw.org. Retrieved October 4, 2007.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 John R. Swanton, Source Material for the Social and Ceremonial Life of the Choctaw Indians. (Tuscaloosa and London: The University of Alabama Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0817311094)

- ↑ Mike Ward Irish Repay Choctaw Famine Gift: March Traces Trail of Tears in Trek for Somalian Relief American-Stateman Capitol Staff, 1992. Retrieved October 4, 2007.

- ↑ "Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma" (report), Choctaw Nation, 66, webpage: ChNat-66. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- ↑ Greg O'Brien, Choctaws in a Revolutionary Age, 1750-1830. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2002, ISBN 0803286228)

- ↑ Randy Jimmie and Leonard Jimmie, NANIH WAIYA Magazine (1974) I (3)

- ↑ Jena Band of Choctaw Indianswww.jenachoctaw.org. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Blanchard, Kendall. The Mississippi Choctaws at Play: The Serious Side of Leisure. University of Illinois Press, 1981. ISBN 0252008669

- Bushnell, David I. 1909. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 48: The Choctaw of Bayou Lacomb, St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Byington, Cyrus. 1915. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 46: A Dictionary of the Choctaw Language. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Carson, James Taylor. 1999. Searching for the Bright Path: The Mississippi Choctaws from Prehistory to Removal. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Ferguson, Bob. 1997. Choctaw Chronology. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- Galloway, Patricia. 1998. Choctaw Genesis 1500-1700. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803270704.

- Haag, Marcia and Henry Willis. 2001. Choctaw Language & Culture: Chahta Anumpa. Norman, Okla: University of Oklahoma Press. Bilingual edition 2007. ISBN 978-0806138558

- Jimmie, Randy., and Jimmie, Leonard. NANIH WAIYA Magazine (1974) 1 (3).

- Lincecum, Gideon. Pushmataha: A Choctaw Leader and His People. 2004. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

- Mould, Tom. 2004. Choctaw Tales. Jackson, Miss: University Press of Mississippi.

- O'Brien, Greg. 2002. Choctaws in a Revolutionary Age, 1750-1830. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- O'Brien, Greg. 2001. Mushulatubbee and Choctaw Removal: Chiefs Confront a Changing World Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- O'Brien, Greg. 2001. Pushmatha: Choctaw Warrior, Diplomat, and Chief Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- Pesantubbee, Michelene E. 2005. Choctaw Women in a Chaotic World: The Clash of Cultures in the Colonial Southeast. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico.

- Romans, Bernard. Natural History of East and West Florida. New York, 1775. online

- Spann, S. G., Choctaw Indians as Confederate Soldiers. www.choctaw.org.Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- Swanton, John R. 2001. Source Material for the Social and Ceremonial Life of the Choctaw Indians. Tuscaloosa and London: The University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0817311094

- Tingle, Tim. 2003. Walking the Choctaw Road. El Paso, Tex: Cinco Puntos Press.

- Mississippi Choctaw Reservation and Off-Reservation Trust Land, Mississippi United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- Waldman, Carl. 2006. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. Checkmark Books. ISBN 978-0816062744

External links

All links retrieved December 10, 2023.

- Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians (official site).

- Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma (official site).

- Jena Band of Choctaw Indians (official site).

- Mississippi Legislature returns Nanih Waiya.

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.