Bald Eagle

| Bald Eagle | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Haliaeetus leucocephalus (Linnaeus, 1766) | ||||||||||||||

Bald Eagle range

██ Resident, breeding██ Summer visitor, breeding██ Winter visitor██ On migration only██ Star: accidental records

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

Falco leucocephalus Linnaeus, 1766 |

Bald eagle is the common name for a North American bird of prey, (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), that is most recognizable as the national bird and symbol of the United States. Its range includes most of Canada and Alaska, all of the contiguous United States, and northern Mexico. It is found near large bodies of open water with an abundant food supply and old-growth trees for nesting.

The species was on the brink of extirpation in the continental United States (while flourishing in much of Alaska and Canada) late in the twentieth century, largely because of anthropogenic factors (hunting, loss of habitat, pollution). However, just as human activity lead to its reduction to only about 412 nesting pairs in the continental United States by the 1950s, regulations and environmental education advanced its recovery. The bald eagle now has a stable population and has been officially removed from the U.S. federal government's list of endangered species. The bald eagle was officially reclassified from "Endangered" to "Threatened" on July 12, 1995 by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service. On July 6, 1999, a proposal was initiated "To Remove the Bald Eagle in the Lower 48 States From the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife." It was delisted on June 28 2007.

Overview

Eagles are large birds of prey (a bird that hunts for food primarily on the wing, also known as a raptor) that mainly inhabit Eurasia and Africa. Outside this area, just two species (the Bald and golden eagles) are found in North America north of Mexico, with a few more species in Central and South America, and three in Australia.

Eagles are members of the bird order Falconiformes (or Accipitriformes, according to alternative classification schemes), family Accipitridae, and belong to several genera that are not necessarily closely related to each other in any sort of way.

Eagles are differentiated from other birds of prey mainly by their larger size, more powerful build, and heavier head and bill. Even the smallest eagles, like the booted eagle (which is comparable in size to a common buzzard or red-tailed hawk), have relatively longer and more evenly broad wings, and more direct, faster flight. Most eagles are larger than any other raptors apart from the vultures.

Like all birds of prey, eagles have very large powerful hooked beaks for tearing flesh from their prey, strong legs, and powerful talons. They also have extremely keen eyesight to enable them to spot potential prey from a very long distance.[1] This keen eyesight is primarily contributed by their extremely large pupils, which cause minimal diffraction (scattering) of the incoming light.

Bald eagles are part of a group of eagles known as "sea eagles," birds of prey in the genus Haliaeetus. Bald eagles have two known sub-species and forms a species pair with the white-tailed eagle (i Eurasia). A species pair is a group of species that satisfy the biological definition of species—that is, they are reproductively isolated from each other—but which are not morphologically distinguishable.

The genus Haliaeetus is possibly one of the oldest genera of living birds. A distal left tarsometatarsus (DPC 1652) recovered from early Oligocene deposits of Fayyum, Euzbakistan (Jebel Qatrani Formation, around 33 million years ago (mya) is similar in general pattern and some details to that of a modern sea-eagle.[2] The genus was present in the middle Miocene (12-16 mya) with certainty.[3]

Description

The Bald eagle, (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), is a large bird, with an adult body length of 71-96 centimeters (28-38 inches), a wingspan of 168–244 centimeters (66–88 inches), and a weight of 3–6.3 kilograms (6.6–14 pounds); females are about 25 percent larger than males.[4] Adult females have a wingspan of up to 2.44 meters (88 inches), while adult males may be as small as 1.68 meters (66 inches). Adult females weigh approximately 5.8 kilograms (12.8 pounds), males weigh 4.1 kilograms (9 pounds).[5] The size of the bird varies by location; the smallest specimens are those from Florida, where an adult male may barely exceed 2.3 kilograms (5 pounds) and a wingspan of 1.8 meters (6 feet). The largest are Alaskan birds, where large females may exceed 7.5 kilograms (16.5 pounds) and have a wingspan of over 2.4 meters (8 feet).[6]

The adult bald eagle has an evenly brown body with a white head and tail. The beak, feet, and irises are bright yellow. Males and females are identical in plumage coloration.

Juveniles are completely brown except for the yellow feet. The plumage of the immature is brown, speckled with white until the fifth (rarely fourth, very rarely third) year, when it reaches sexual maturity.[7] Immature bald eagles are distinguishable from the golden eagle in that the former has a more protruding head with a larger bill, straighter edged wings that are held flat (not slightly raised) and with a stiffer wing beat, and feathers which do not completely cover the legs.[8] Also, the immature Bald Eagle has more light feathers in the upper arm area, especially around the very top of the arm.

The tail of the bald eagle is moderately long and slightly wedge-shaped. The legs are unfeathered, and the toes are short and powerful with long talons. The highly developed talon of the hind toe is used to pierce the vital areas of prey while it is held immobile by the front toes. The beak is large and hooked, with a yellow cere.[9]

The diet of a bald eagle consists mainly of fish, but it is an opportunistic feeder. It hunts fish by swooping down and snatching the fish out of the water with its talons.

The bald eagle is sexually mature at four years or five years of age. It builds the largest nest of any North American bird, up to 4 meters (13 feet) deep, 2.5 meters (8 feet) wide, and one metric ton (1.1 short ton) in weight.[10]

This sea eagle gets both its common and scientific names from the distinctive appearance of the adult's head. Bald in the English name is derived from the word "piebald," and refers to the white head and tail feathers and their contrast with the darker body. The scientific name is derived from Haliaeetus, New Latin for "sea eagle" (from the Ancient Greek haliaetos), and leucocephalus, Latinized Ancient Greek for "white head," from λευκος leukos ("white") and κεφαλη kephale ("head").[11][12]

Habitat and range

The bald eagle prefers habitats near seacoasts, rivers, large lakes, and other large bodies of open water with an abundance of fish. Studies have shown a preference for bodies of water with a circumference greater than 11 kilometers (7 miles), and lakes with an area greater than 10 km² (3.8 square miles) are optimal for breeding bald eagles.[13]

The bald eagle requires old-growth and mature stands of coniferous or hardwood trees for perching, roosting, and nesting. Selected trees must have good visibility, an open structure, and proximity to prey, but the height or species of tree is not as important as an abundance of comparatively large trees surrounding the body of water. Forests used for nesting should have a canopy cover of less than 60 percent, and as low as 20 percent, and be in close proximity to water.[14]

The bald eagle is extremely sensitive to human activity, and occurs most commonly in areas free of human disturbance. It chooses sites more than 1.2 kilometers (0.75 miles) from low-density human disturbance and more than 1.8 kilometers (1.2 miles) from medium- to high-density human disturbance.[15]

The bald eagle's natural range covers most of North America, including most of Canada, all of the continental United States, and northern Mexico. It is the only sea eagle native to only North America. The bird itself is able to live in most of North America's varied habitats from the bayous of Louisiana to the Sonoran Desert and the eastern deciduous forests of Quebec and New England. Northern birds are migratory, while southern birds are resident, often remaining on their breeding territory all year. The bald eagle previously bred throughout much of its range but at its lowest population was largely restricted to Alaska, the Aleutian Islands, northern and eastern Canada, and Florida.[16]

The bald eagle has occurred as a vagrant at least twice in Ireland; a juvenile was shot illegally in Fermanagh on January 11 1973 (misidentified at first as a white-tailed eagle), and an exhausted juvenile was captured in Kerry on November 15 1987.[17]

Bald eagles will also congregate in certain locations in winter. From November until February, one to two thousand birds winter in Squamish, British Columbia, about halfway between Vancouver and Whistler. The birds primarily gather along the Squamish and Cheakamus Rivers, attracted by the salmon spawning in the area.[18]

Taxonomy

The bald eagle was one of the many species originally described by Linnaeus in his eighteenth century work Systema Naturae, under the name Falco leucocephalus.[19]

There are two recognized subspecies of Bald Eagle:[20]

- H. l. leucocephalus (Linnaeus, 1766) is the nominate subspecies. It is separated from H. l. alascanus at approximately latitude 38° N, or roughly the latitude of San Francisco.[21] It is found in the southern United States and Baja California.[22]

- H. l. washingtoniensis (Audubon, 1827), synonym H. l. alascanus Townsend, 1897, the northern subspecies, is larger than southern nominate leucocephalus. It is found in the northern United States, Canada, and Alaska.[23] This subspecies reaches further south than latitude 38° N on the Atlantic Coast, where they occur in the Cape Hatteras area.[24]

The bald eagle forms a species pair with the Eurasian white-tailed eagle. This species pair consists of a white-headed and a tan-headed species of roughly equal size. The white-tailed eagle also has overall somewhat paler brown body plumage. The pair diverged from other sea eagles at the beginning of the Early Miocene (around 10 million years before present) at the latest, but possibly as early as the Early/Middle Oligocene, 28 million years before present, if the most ancient fossil record is correctly assigned to this genus.[25] The two species probably diverged in the North Pacific, as the white-tailed eagle spread westwards into Eurasia and the Bald Eagle spread eastwards into North America.[26]

Relationship with humans

Population decline and recovery

Once a common sight in much of the continent, the bald eagle was severely affected in the mid-twentieth century by a variety of factors. These factors included widespread loss of suitable habitat and illegal shooting, the later of which was described as "the leading cause of direct mortality in both adult and immature bald eagles," according to a 1978 report in the Endangered Species Technical Bulletin. In 1984, the National Wildlife Federation listed hunting, power line electrocution, and collisions in flight as the leading causes of eagle deaths. Bald eagle populations have also been negatively affected by oil, lead, and mercury pollution, and by human and predator intrusion.[27]

Another factor considered as impacting eagle populations is the thinning of egg shells, attributed to the use of the pesticide DDT.[28] Bald eagles, like many birds of prey, were believed to be especially affected by DDT due to biomagnification. DDT itself was not lethal to the adult bird, but it is believed that it interfered with the bird's calcium metabolism, making the bird either sterile or unable to lay healthy eggs. Female eagles laid eggs that were too brittle to withstand the weight of a brooding adult, making it nearly impossible to produce young.

By the 1950s there were only 412 nesting pairs in the 48 contiguous states of the US.

The species was first protected in the U.S. and Canada by the 1918 Migratory Bird Treaty, later extended to all of North America. The 1940 Bald Eagle Protection Act in the U.S., which protected the Bald Eagle and the golden eagle, prohibited commercial trapping and killing of the birds. The bald eagle was declared an endangered species in the U.S. in 1967, and amendments to the 1940 act between 1962 and 1972 further restricted commercial uses and increased penalties for violators. Also in 1972, DDT was banned in the United States.[29] DDT was completely banned in Canada in 1989, though its use had been highly restricted since the late 1970s.[30]

With regulations in place and DDT banned, the eagle population rebounded. The bald eagle can be found in growing concentrations throughout the United States and Canada, particularly near large bodies of water. In the early 1980s, the estimated total population was 100,000 birds, with 110,000–115,000 by 1992. The U.S. state with the largest resident population is Alaska, with about 40,000–50,000 birds, with the next highest population being the Canadian province of British Columbia with 20,000–30,000 birds in 1992.

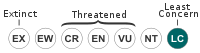

The bald eagle was officially removed from the U.S. federal government's list of endangered species on July 12, 1995 by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, when it was reclassified from "Endangered" to "Threatened." On July 6, 1999, a proposal was initiated "To Remove the Bald Eagle in the Lower 48 States From the List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife." It was delisted on June 28, 2007.[31]It has also been assigned a risk level of Least Concern category on the IUCN Red List.[32]

In captivity

Permits are required to keep bald eagles in captivity in the United States. Permits are only issued to public educational institutions, and the eagles which they show are permanently injured individuals that cannot be released to the wild. The facilities where eagles are kept must be equipped with adequate caging and facilities, as well as workers experienced in the handling and care of eagles. Bald eagles cannot legally be kept for falconry in the United States. As a rule, the bald eagle is a poor choice for public shows, being timid, prone to becoming highly stressed, and unpredictable in nature. The bald eagle can be long-lived in captivity if well cared for, but does not breed well even under the best conditions.[33] In Canada, a license is required to keep bald eagles for falconry.[34]

National bird of the United States

The bald eagle is the national bird of the United States of America. It is one of the country's most recognizable symbols, and appears on most of its official seals, including the Seal of the President of the United States.

Its national significance dates back to June 20 1782, when the Continental Congress officially adopted the current design for the Great Seal of the United States including a bald eagle grasping arrows and an olive branch with its talons.[35]

In 1784, after the end of the Revolutionary War, Benjamin Franklin wrote a famous letter from Paris to his daughter, criticizing the choice and suggesting the wild turkey as a better representative of American qualities. He described the Bald Eagle as "a Bird of bad moral character," who, "too lazy to fish for himself" survived by robbing the osprey of its catch. He also called the bald eagle "a rank Coward" who was easily driven from a perch by the much smaller kingbird. In the letter, Franklin wrote that he favored the turkey, "a much more respectable Bird," which he described as "a little vain & silly [but] a Bird of Courage."[36]

Despite Franklin's objections, the Bald Eagle remained the emblem of the United States. It can be found on both national seals and on the back of several coins (including the quarter dollar coin until 1999), with its head oriented towards the olive branch. Between 1916 and 1945, the Presidential Flag showed an eagle facing to its left (the viewer's right), which gave rise to the urban legend that the seal is changed to have the eagle face towards the olive branch in peace, and towards the arrows in wartime.[37]

Role in Native American culture

The Bald Eagle is a sacred bird in some North American cultures, and its feathers, like those of the golden eagle, are central to many religious and spiritual customs among Native Americans. Eagles are considered spiritual messengers between gods and humans by some cultures.[38] Many pow wow dancers use the eagle claw as part of their regalia as well. Eagle feathers are often used in traditional ceremonies, particularly in the construction of regalia worn and as a part of fans, bustles, and head dresses. The Lakota, for instance, give an eagle feather as a symbol of honor to person who achieves a task. In modern times, it may be given on an event such as a graduation from college.[39]The Pawnee considered eagles as symbols of fertility because their nests are built high off the ground and because they fiercely protect their young. The Kwakwaka'wakw scattered eagle down to welcome important guests.[40]

During the Sun Dance, which is practiced by many Plains Indian tribes, the eagle is represented in several ways. The eagle nest is represented by the fork of the lodge where the dance is held. A whistle made from the wing bone of an eagle is used during the course of the dance. Also during the dance, a medicine man may direct his fan, which is made of eagle feathers, to people who seek to be healed. The medicine man touches the fan to the center pole and then to the patient, in order to transmit power from the pole to the patient. The fan is then held up toward the sky, so that the eagle may carry the prayers for the sick to the Creator.[41]

Current eagle feather law stipulates that only individuals of certifiable Native American ancestry enrolled in a federally recognized tribe are legally authorized to obtain bald or golden eagle feathers for religious or spiritual use. The constitutionality of these laws has been questioned by Native American groups on the basis that it violates the First Amendment by affecting ability to practice their religion freely.[42] Additionally, as only members of federally recognized tribes are legally allowed to possess eagle feathers, this prevents non-federally recognized tribe members from practicing religion freely. The laws have also been criticized on grounds of racial preferences and infringements on tribal sovereignty.[43]

Notes

- ↑ R. Shlaer, "An eagle's eye: Quality of the retinal image," Science 176(1972)(4037): 920-922. Retrieved November 20, 2007.

- ↑ D. Rasmussen, O. Tab, L. Storrs, and E. L. Simons, "Fossil birds from the Oligocene Jebel Qatrani Formation, Fayum Province, Egypt," Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 62(1987): 1-20.

- ↑ K. Lambrecht, Handbuch der Palaeornithologie (Berlin: Gebrüder Bornträger, 1933).

- ↑ J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, and J. Sardals, eds., Handbook of the Birds of the World], Volume 2. (Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, 1994). ISBN 8487334156.

- ↑ D. M. Bird, The Bird Almanac: A Guide to Essential Facts and Figures of the World's Birds. (Ontario: Firefly Books, 2004. ISBN 1552979259).

- ↑ Cornell Lab of Ornithology, "Bald Eagle, Haliaeetus leucocephalus,", Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved:2007-06-21

- ↑ M. S. Harris, "Bald Eagle Haliaeetus leucocephalus," University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ↑ D. Sibley, The Sibley Guide to Birds. (National Audubon Society, 2000. ISBN 0679451226)

- ↑ Cornell Lab of Ornithology, "Bald Eagle, Haliaeetus leucocephalus,", Cornell Lab of Ornithology (2003). Retrieved:2007-06-21

- ↑ name=hbw

- ↑ J. Dietz, "What's in a name," Smithsonian National Zoological Park (2003). Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ↑ H. G. Liddell, and R. S. George, A Greek-English Lexicon, abridged edition. (United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 1980). ISBN 0199102074.

- ↑ S. A. Snyder, "Haliaeetus leucocephalus, In Fire Effects Information System, Online, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service (1993). Retrieved December 22, 2007

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ J. Bull and J. Farrand, Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds: Eastern Region. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987. ISBN 0394414055), 468-469.

- ↑ British Ornithologists Union Records Committee, "25th Report,"British Ornithologists' Union (1998). Retrieved August 19, 2007.

- ↑ H. Rutledge, "Where to view bald eagles," BaldEagleInfo.com (2007). Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ↑ C. Linnaeus, Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata. (Holmiae. Laurentii Salvii., 1766).

- ↑ Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS), "Haliaeetus leucocephalus," Integrated Taxonomic Information System (n. d.). Retrieved June 21, 2007.

- ↑ Pacific Wildlife Foundation, "Bald Eagle Haliaeetus leucocephalus," The Pacific Wildlife Foundation (n. d). Retrieved June 27, 2007.

- ↑ N. L. Brown, "Bald eagle Haliaeetus leucocephalus" Endangered Species Recovery Program (n.d). Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Pacific Wildlife Foundation

- ↑ M. Wink, P. Heidrich, and C. Fentzloff. "A mtDNA phylogeny of sea eagles (genus Haliaeetus) based on nucleotide sequences of the cytochrome b gene," Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 24 (1996): 783-791. Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ↑ Bald Eagles Info, "Bald Eagle Habitat," Bald-Eagles.info. (2006). Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ↑ S. Milloy, "Bald eagle," Fox News July 6, 2006. Retrieved August 15, 2008.

- ↑ L. Brown, Birds of Prey: Their Biology and Ecology. (london: Hamlyn, 1976).

- ↑ United States Environmental Protection Agency, "DDT ban takes effect," EPA press release December 31, 1972. Retrieved August 22, 2007.

- ↑ J. Barrera, "Agent Orange has left deadly legacy: Fight continues to ban pesticides and herbicides across Canada,", Nben.ca (July 2005). Retrieved August 22, 2007.

- ↑ U.S. Department of the Interior, [http://www.doi.gov/news/07_News_Releases/070628.html "Bald eagle soars off endangered species list," U.S. Department of the Interior. (June 28, 2007). Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- ↑ BirdLife International, "Haliaeetus leucocephalus," 2006 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2006. Retrieved August 21, 2007.

- ↑ J. R. Maestrelli and S. N. Wiemeyer, "Breeding bald eagles in captivity," The Wilson Bulletin 87(1975). Retrieved August 19, 2007].

- ↑ Ministry of Attorney General of Canada, "Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act, 1997," Ministry of Attorney General (1997). Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- ↑ National Archives and Records Administration, "Original Design of the Great Seal of the United States,", National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C. (1986). Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ B. Mikkelson and D. P. Mikkelson, "A turn of the head,". Snopes.com (n.d.). Retrieved August 19, 2007.

- ↑ J. Collier, "The sacred messengers," Mashantucket Pequot Museum (2003).

- ↑ D. Melmer, "Bald eagles may come off threatened list," Indian Country Today June 11, 2007.

- ↑ S. C. Brown and L. J. Averill, Sun Dogs and Eagle Down: The Indian Paintings of Bill Holm (University of Washington Press, 2000. ISBN 029597947X). Retrieved December 22, 2007.

- ↑ E. A. Lawrence, "The symbolic role of animals in the Plains Indian sun dance,". Society & Animals Journal of Human-Animal Studies 1(1993)(1). Retrieved December 22, 2007].

- ↑ A. M. DeMeo, Access to eagles and eagle parts: Environmental protection v. Native American free exercise of religion. Hastings Constitutional Law Quarterly 22(1995)(3): 771-813. Retrieved August 22, 2007. Retrieved August 22, 2007.

- ↑ T. S. Boradiansky, "Conflicting values: The religious killing of federally protected wildlife," University of New Mexico School of Law (1990). Retrieved August 23, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bird, D.M. The Bird Almanac: A Guide to Essential Facts and Figures of the World's Birds. Ontario: Firefly Books, 2004. ISBN 1552093239

- Brown, L. Birds of Prey: Their Biology and Ecology. London: Hamlyn, 1976. ISBN 0600313069

- Brown, S. C. and L. J. Averill, Sun Dogs and Eagle Down: The Indian Paintings of Bill Holm University of Washington Press, 2000. ISBN 029597947X

- del Hoyo, J. A. Elliott, and J. Sardals, (eds.) Handbook of the Birds of the World, Volume 2. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions, 1994. ISBN 8487334156

- Liddell, H.D. and R. S. George. A Greek-English Lexicon, abridged edition. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 1980. ISBN 0199102074

- Linnaeus, Carolus. Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata. Holmiae. Laurentii Salvii., 1766.

- Rasmussen, D., O. Tab, L. Storrs, and E. L. Simons, "Fossil birds from the Oligocene Jebel Qatrani Formation, Fayum Province, Egypt," Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 62(1987).

- Sibley, J. The Sibley Guide to Birds. National Audubon Society, 2000. ISBN 0679451226

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.