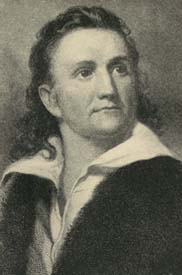

John James Audubon

| John James Audubon |

|---|

John James Audubon

|

| Born |

| April 26, 1785 (then called : Saint Domingue) |

| Died |

| January 27, 1851 |

John James Audubon (April 26, 1785 â January 27, 1851) was a self-taught American ornithologist, naturalist, hunter, and painter. He painted, cataloged, and described the birds of North America, as well as its mammals. Sailing between Europe and America for more than a decade, spending enough time at home to hunt and draw his subjects and enough time in Liverpool, Edinburgh, London, and Paris to display his work and secure subscribers for publication, made it possible for him to continue his quest to draw each species of American bird.

In March, 2000, Audubon's complete, double-elephant folio copy of The Birds of America came up for sale at Christie's (Auction House) New York and fetched $8.8 million. Single prints, taken from dismembered copies, change hands at over $100,000 apiece, such is the fame and rarity of the most celebrated ornithological work ever published.

Life

Audubon was born in Haiti (then called Saint-Domingue), the illegitimate son of Jean Audubon, a French sea captain and slavemaster, and Jeanne Rabin, his SpanishâCreole chambermaid.[1] The circumstances of his parentage may have been the basis for later claims that he was instead Louis XVII, the "Lost Dauphin" of France. Since Audubon's parents weren't married, he was first named Jean Rabin.

His father took him to Nantes, France, to be raised by his wife, Anne Moynet.[2] He was formally adopted in March 1789, and named Jean-Jacques Fougere Audubon, which he later Americanized. He was educated in Paris, where he took lessons from the French painter Jacques-Louis David.[3]

In 1803, his father obtained a false passport for him to travel to the United States to avoid the Napoleonic Wars. He caught yellow fever and the sea captain placed him in a boarding house run by Quaker women who nursed him to recovery and taught him the unique Quaker form of English. The destination was his father's family farm in Mill Grove, near Philadelphia,[4] where he took no interest in the running of it and instead went hunting. In 1803, he began the study of natural history by conducting the first known bird-banding on the continent: He tied yarn to the legs of Eastern Phoebes and determined that they returned to the same nesting spots year after year. As an intense young man, Audubon had many talents, he danced well, played music, and was an accomplished horseman. He seemed to know everything about animals and birds. He could fence and swim and was a superb marksman. As a regular visitor at Fatland Ford, he endeared himself to William Bakewell and his affluent English family, now resettled, raising livestock and pointing dogs. In that year, he became engaged to one of his neighbors' daughters, Lucy Bakewell, whom he married in 1808. He also began drawing and painting birds. In later years, he claimed to have hunted in the Appalachians with Daniel Boone.

He started a general store in Louisville, Kentucky, lived in Henderson, Kentucky, and witnessed the 1811-1812 earthquakes. He had two sons: Victor Gifford (b. June 12, 1809) and John Woodhouse (b. November 30, 1812), and two daughters: Lucy (1815-1817) and Rose (1819).

After years of business success in Pennsylvania and Kentucky, he went bankrupt. This compelled him to pursue his nature study and painting more vigorously, and he sailed down the Mississippi with his gun, paintbox, and assistant, intent on finding and painting all the birds of North America.

On his arrival in New Orleans in the spring of 1821, he lived for a time at 706 Barracks Street. That summer, he moved upriver to the Oakley Plantation in the Felicianas to teach drawing to Eliza Pirrie, the young daughter of the owners, and where he spent much of his time roaming and painting in the woods. (The plantation, located at 11788 Highway 965, between Jackson and St. Francisville, is now Audubon State Historic Site, and guided tours are available almost daily.)

When he first painted and drew birds, they were what they looked like, dead and lifeless. Seeking inspiration, he stopped drawing and just looked at birds. One morning, he awoke early from a dream, in which he painted birds and, inspired, immediately rode off to purchase different gauges of wire. Quickly, he went out and shot a Kingfisher, then used fixed wires to prop it up, restoring a natural position. By attaching wires in various parts of the bird he could achieve a more natural look, even being able to open the eyelids, as if to bring them back to life. To draw or paint birds, he shot them first, using fine shot to prevent them from being torn to pieces. His paintings of birds are set true-to-life in their natural habitat. This was in stark contrast with the stiff representations of birds by his contemporaries, such as Alexander Wilson. Audubon once wrote: "I call birds few when I shoot less than one hundred per day." One of his biographers, Duff Hart-Davis, reveals, "The rarer the bird, the more eagerly he pursued it, never apparently worrying that by killing it he might hasten the extinction of its kind."

It was his lust for knowledge rather than lust for blood that drove him on. He was always searching, not only for new species but for small variations within speciesâbetween male and female, between juvenile and matureâand at the same time seeking to defray his expenses by collecting skins that he could sell to European museums.

Since he had no other income, Audubon eked out a living selling portraits on demand, while his wife, Lucy, worked as a tutor to rich plantation families. He sought a publisher for his birds in Philadelphia but was rebuffed, in part because he had earned the enmity of some of the city's leading scientists at the Academy of Natural Sciences.

Many facets of Audubon's character and behavior can be inferred from his own writing. A devout Quaker, he said his prayers out loud every night, kneeling beside his bed and firmly believed that the natural world, along with all its creatures, had been created by God. He once wrote that whenever he set eyes on a "Red Indian," he felt, "the greatness of our Creator in all its splendor, for there I see a man naked from His hand and yet free from acquired sorrow."

His admiration of nature, in all its forms, was unbounded and he was haunted by the fear that humankind had already begun to destroy the environment. Although vain about his looks, he was racked with doubts about his competence as an artist and his lack of formal education. He was ambidextrous, disliked heights, and suffered from vertigo. In spite of his lack of learning, he had a good knowledge of literature, as Lucy had often read to him at home in the evenings. He was fond of music and played the flute well. Endowed with unquenchable energy, he dreaded having nothing to do.

Europe

Finally, in 1826, he set sail with his portfolio to Liverpool. A friend from New Orleans, Vincent Nolte, furnished him with an excellent, down-to-earth, letter of introduction to Richard Rathbone, of a powerful trading firm, Rathbone Brothers & Co., reading that, "Audubons' 400 drawings, I should think convey a far better idea of American birds than all the stuffed birds of all the museums put together."

The British couldn't get enough of images of backwoods America and he was an instant success. By chance Audubon arrived in England at a time when interest in ornithology was growing rapidly and several outstanding bird artists were at work. The study of birds was by no means new in England and the renewal of activity was auspicious for the American artist as it raised general awareness of ornithological illustration.

An anonymous writer described the backwoods stranger as:

The tall and somewhat stooping form, the clothes not made by a West End but a Far West tailor, the steady, rapid, springing step, the long hair, the aquiline features and the glowing, angry eyesâthe expression of a handsome man conscious of ceasing to be young and an air and manner which told you that whoever you might be, he was John Audubon, will never be forgotten by anyone who knew or saw him.

During his visit to Europe, he kept a voluminous journal in which he chronicled his daily encounters. In this, he constantly addressed his wife and "beloved friend," Lucy, as if the diaries were a series of letters and it was as though he was talking to her. Although often given to skirting the truth as to details of his life to others, it is assumed that most of what he wrote here was true. He had claimed for instance, in the past, that his father had been an admiral in the French navy, when in fact he had only been a lieutenant and that his mother had been a Spanish Creole, when in reality she was French. When he wrote about early episodes in his life, he often ran different events together, whether intentionally or not is difficult to know. However, in this case his diary contains passages of painfully honest doubt, self-criticism, and reproach.

He was lionized as "The American Woodsman" and raised enough money to publish his Birds of America. This consisted of hand-colored, life-size prints made from engraved plates measuring around 39 by 26 inches. This original edition was engraved in aquatint by Robert Havell junior; known as the Double Elephant folio, it is often regarded as the greatest picture book ever produced. All 435 of the preparatory watercolors for "The Birds of America" are currently housed at the New-York Historical Society in New York City.

He knew that although Bohn (the publisher) had come around to the double-elephant format, some of his friends were worried by the size of the sheets and he himself worried that the published work was going to be "rather bulky," but his heart remained on presenting even the biggest birds at life-size.

Even King George IV was an avid fan of Audubon. Audubon was elected a fellow of London's Royal Society. In this, he followed the footsteps of Benjamin Franklin, who was the first American fellow. While in Edinburgh to seek subscriptions for his book, he gave a demonstration of his method of using wires to prop up birds at professor Robert Jameson's Wernerian Natural History Association with the student Charles Darwin in the audience and also visited the dissecting theater of the anatomist Robert Knox (not long before Knox became associated with Burke and Hare).

He paid tribute, "To Britain I owe nearly all my success. She has furnished the artists through whom all my labors were to be presented to the world; she has granted me the highest patronage and honors; in a word, she had thus far supported the prosecution of my illustrations. To Britain, therefore, I shall be ever grateful."

In Paris, a five year-old letter of introduction led Audubon to a meeting with Pierre Joseph Redoute, the elderly flower painter, who admired his work so much that he arranged for him to meet the Duc d'Orleans who on seeing a print of the Baltimore Orioles, declared, "this surpasses all that I have see!" Promising references to many heads of state he helped secure many subscriptions including that of the King Charles X and other members of the Royal family.

He followed his Birds of America up with a companion work, Ornithological Biographies, life histories of each species written with Scottish ornithologist William MacGillivray. Both the books of paintings and the biographies were published between 1827 and 1839. The greatest production, published from 1831 to 1893, consisted of five volumes of biographies of birds and four volumes of portraits of birds. The portraits contained over four hundred drawings, colored and life-size.

Returning home

On return to his native land after an absence of nearly three years, Audubon did not at first return to his wife, Lucy. Writing from England he said, "it is not my wish to go to Louisiana, if I can help it." He wished to go further south and west, "Thou knowest I must draw hard from nature every day that I am in America." He intended to put work before pleasure or personal gratification.

During that time, Audubon continued making expeditions in North America and bought an estate on the Hudson River, now Audubon Park. In 1842, he published a popular edition of Birds of America in the United States. His final work was on mammals, the Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America, which was written in collaboration with his good friend Rev. John Bachman (of Charleston, South Carolina) who supplied much of the scientific text. It was completed by his sons and son-in-law and published posthumously.

He may be buried in the Trinity Churchyard Cemetery at 155th Street and Broadway in Manhattan, New York, where there is an imposing monument in his honor, but the exact location of his remains is unclear.

Legacy

Audubon's biographer, Francis Hobart Herrick, writing in 1917, described the making of the Birds of America as:

one of the most remarkable and interesting undertakings in the history of literature and science in the nineteenth century. Unique, as it was in every detail of its workmanship, it will remain for centuries a shining example of the triumph of human endeavor and of the spirit and will of man.

The National Audubon Society was incorporated and named in his honor in 1905. Several towns and one county (in Iowa) also bear his name. The John James Audubon Parkway in Amherst, New York, which encircles the main campus of the University at Buffalo, is named in his honor.

In Henderson, Kentucky, he is remembered by the 692-acre John James Audubon State Park. The Audubon Museum houses many of Audubonâs original watercolors, oils, engravings and personal memorabilia. The Nature Center features a wildlife observatory, which nurtures Audubonâs own love for nature and the great outdoors. The Park offers facilities for camping, hiking, fishing, swimming, golf, and tennis.

In Natchez, Mississippi, there is a gallery and, at one time, there was a tableau in the Natchez Pageant dedicated to him.

Posthumous collections

- John James Audubon, Writings & Drawings (Christoph Irmscher, ed.) (The Library of America, 1999) ISBN 978-1883011680.

- John James Audubon, The Audubon Reader (Richard Rhodes, ed.) (Everyman Library, 2006) ISBN 1400043697

- John James Audubon, Capturing Nature, The Writings and Art of John James Audubon, Edited by Peter and Connie Roop with Illustrations by Rick Farley, 1993, Walker Publishing Company Inc., ISBN 0802782043.

Notes

- â Rootsweb.com, John James Audubon. Retrieved April 16, 2008.

- â www.audubon.org, Audubon Biography. Retrieved April 16, 2008.

- â Maurice Garland Fulton, Southern Life in Southern Literature (Kessinger Publishing, 1917). ISBN 0766146243

- â About.com, John James Audubon. Retrieved July 3, 2015.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Fulton, Maurice Garland. Southern Life in Southern Literature. Kessinger Publishing, 1917. ISBN 0766146243

- Hart, Davis Duff. Audubon's Elephant: America's Greatest Naturalist and the Making of the Birds of America. Henry Holt and Company, LLC., 2004. ISBN 0805075682

- Sounder, William. Under A Wild Sky: John James Audubon and the Making of the Birds of America. North Point Press, 2004. ISBN 0865476713

- Stevenson, Janet. Painting America's Wildlife, John James Audubon. Chicago: Kingston House, 1961.

External links

All links retrieved January 30, 2025.

- Audubon biography National Audubon Society.

- Audubon Prints.

- Audubon House & Tropical Gardens.

- National Audubon Society.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.