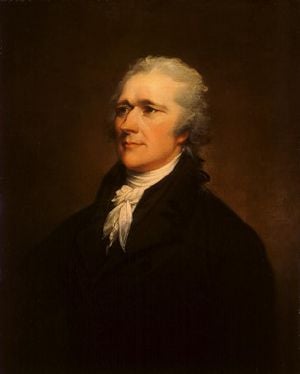

John Jay

| John Jay | |

| |

1st Chief Justice of the United States

| |

| In office October 19, 1789 – June 29, 1795 | |

| Nominated by | George Washington |

|---|---|

| Preceded by | None |

| Succeeded by | John Rutledge |

2nd Governor of New York

| |

| In office July 1, 1795 – June 30, 1801 | |

| Lieutenant(s) | Stephen Van Rensselaer |

| Preceded by | George Clinton |

| Succeeded by | George Clinton |

| Born | December 12, 1745 New York, New York |

| Died | May 17 1829 (aged 83) Westchester County, New York |

| Spouse | Sarah Livingston |

| Religion | Episcopalian |

John Jay (December 12, 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American politician, statesman, revolutionary, diplomat, and jurist, best known as the first Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Considered one of the "Founding Fathers" of the United States, Jay served in the Continental Congress and was elected president of that body in 1778. During and after the American Revolution, he was the ambassador to Spain and France, helping to fashion American foreign policy and to secure favorable peace terms from the British and French. He co-wrote the Federalist Papers with Alexander Hamilton and James Madison.

Jay served on the U.S. Supreme Court as the first Chief Justice of the United States from 1789 to 1795. In 1794, he negotiated the Jay Treaty with the British.

A leader of the new Federalist Party, Jay was elected Governor of New York from 1795-1801. He was a leading opponent of slavery and the slave trade in New York. A deeply religious man, in later life he served as president of the American Bible Society.

Early life

John Jay was born on December 12, 1745 to a wealthy family of merchants in New York City. His family, descended from French Huguenot stock, was prominent in New York City. Jay had numerous rich and prominent ancestors and relatives, including his maternal grandfather, Jacobus Van Cortlandt.

Jay attended King's College in New York, the forerunner of today's Columbia University, and began the practice of law in 1768 in partnership with his relative by marriage, Robert Livingston. A successful lawyer, Jay also engaged in land speculation. His first public role came as secretary to the New York committee of correspondence, where he represented the conservative faction that was interested in resisting British violations of American rights while protecting property rights and preserving the rule of law. Jay believed the British tax measures were wrong and that Americans were morally and legally justified in resisting them, but as a delegate to the First Continental Congress in 1774, he sided with those who wanted conciliation with Parliament.

Roles in the American Revolution

Having established a reputation as a “reasonable moderate” in New York, Jay was elected to serve as a delegate to the First and Second Continental Congresses which debated whether the colonies should declare independence. He attempted to reconcile America with Britain, up until the Declaration of Independence. Events such as the burning of Norfolk, Virginia by British troops in January 1776 pushed Jay to support independence. Jay's views became more radical as events unfolded; he became an ardent Patriot.

Jay did not personally attend sessions of the Continental Congress as it debated the independence question. However, in New York, he was instrumental in supporting the cause of independence:

- He served in the New York Provincial Congress in 1776 and 1777 and had a formative influence in drafting its first state constitution.

- He served on the committee of correspondence which was attempting to coordinate the activities of the various colonial states with the actual fighting in Massachusetts.

- He served on the committee to detect and defeat Loyalist conspiracies.

- He served as the first chief justice of the New York Supreme Court from April 1777 to December 1778.

- He was chosen as President of the Continental Congress from December 10, 1778 to September 27, 1779.

Diplomat

The fall of 1779, found Jay selected for a mission to Spain, where he spent a frustrating three years seeking diplomatic recognition, financial support, and a treaty of alliance and commerce. He was to spend the next four years abroad in his nation's service both as commissioner to Spain and then in Paris, where he was a member of the American delegation that negotiated the peace terms ending America's War of Independence with Britain. This process culminated with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in September 1783.

Jay returned to the United States in July, 1784 to discover that he had, in his absence, been elected Secretary for Foreign Affairs. In that role, he was confronted by difficult issues stemming from violations of the Treaty of Paris by both countries—issues that he would later revisit in negotiations with Britain in 1794 and which would be addressed again in the resulting Jay Treaty. Beyond his dealings with Great Britain, Jay succeeded in having the French accept a revised version of the Consular Convention that Benjamin Franklin had earlier negotiated; he attempted to negotiate a treaty with Spain in which commercial benefits would have been exchanged for a renunciation of American access to the Mississippi River for a number of years; and he endeavored, with limited resources, to secure the freedom of Americans captured and held for ransom in Algiers by so-called Barbary Pirates. The frustrations he suffered as Secretary for Foreign Affairs, a post he held until 1789, clearly impressed upon him the need to construct a government more powerful than that under the Articles of Confederation. Though not selected to attend the Philadelphia Convention, he was a leading proponent of the principles that the new Constitution embodied and played a critical role in its ratification.

Slavery

Jay was a leader against slavery after 1777, when he drafted a state law to abolish slavery. It failed to pass, as did a second attempt in 1785. Jay was the founder and president of the New York Manumission Society, in 1785. The Society organized boycotts against newspapers and merchants in the slave trade and provided legal counsel for free blacks who were claimed as slaves.

In the close 1792 gubernatorial election, Jay's antislavery work hurt his election chances in upstate New York Dutch areas, where slavery was still practiced. As a result, he was defeated by the Democratic-Republican candidate, George Clinton. In 1794, Jay angered southern slave-owners when, in the process of negotiating the Jay Treaty with the British, he dropped their demands for compensation for slaves owned by Patriots who had been captured and carried away during the Revolution.

The New York Manumission Society helped enact the gradual emancipation of slaves in New York in 1799, which Jay signed into law as governor. Jay himself made a practice of buying slaves, and then freeing them when they were adults. He judged that their labors had been a reasonable return on their price; he owned eight slaves in 1798, the year before the emancipation act was passed.

The 1799 "Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery" provided that, from July 4 of that year, all children born to slave parents would be free (subject only to apprenticeship) and that the export of slaves would be prohibited. However, these children would be required to serve the mother’s owner until age 28 for males and age 25 for females. The law thus defined the children of slaves as a type of indentured servant while slating them for eventual freedom. Aaron Burr introduced an amendment calling for immediate abolition, but eventually supported it as written.

The last New York slaves were emancipated by July 4, 1827; the process may perhaps have been the largest emancipation in North America before 1861, except for the British Army's recruitment of runaway slaves during the American Revolution.

Secretary of Foreign Affairs

In 1784-1790, Jay served as the second U.S. Secretary of Foreign Affairs, an office which after 1789 became Secretary of State. Among his goals for American foreign policy were:

- to seek the recognition of the young independent nation by the established foreign European powers

- to secure loans from European banks to establish a stable American currency and credit

- to pay off the country's heavy War debt and other commitments

- to secure the infant nation's territorial boundaries under the most-advantageous terms possible and against possible incursions by the Spanish, French, English, and Indians

- to solve regional difficulties among the colonies themselves

- to secure Newfoundland fishing rights

- to establish a robust maritime trade for American goods with new economic trading partners

- to protect American trading vessels against piracy

- to preserve America's reputation at home and abroad

Under the pre-Constitutional system, Jay's office was that of a sort of "prime minister" of United States, with the primary goal of strengthening the fledgling national government. Jay believed that both at home and abroad Americans must adhere to moral principles, among them honesty, patriotism, duty, and hard work along with obedience to God's will. At the same time, he advocated economic and military strength for the United States and worked to avoid crippling foreign entanglements. Through his domestic policies, Jay hoped to remake Congress into a House of Commons. The weakness of Congress under the Articles, however, frustrated Jay.

During the transition from a confederation to a constitutional government, Jay continued to serve as Secretary of Foreign Affairs well into the first administration of George Washington, in fact, remaining in office until Thomas Jefferson returned from France on March 22, 1790.

Federalism

Jay's heavy responsibility was not, however, matched by a commensurate level of authority, which helped to convince him that the national government under the Articles of Confederation was unworkable. Thus, he joined Alexander Hamilton and James Madison in criticizing the Articles. He argued in his "Address to the People of the State of New-York on the Subject of the Federal Constitution" that:

| “ | The Congress under the Articles of Confederation may make war, but are not empowered to raise men or money to carry it on—they may make peace, but without power to see the terms of it observed—they may form alliances, but without ability to comply with the stipulations on their part—they may enter into treaties of commerce, but without power to enforce them at home or abroad… In short, they may consult, and deliberate, and recommend, and make requisitions, and they who please may regard them. | ” |

Jay joined Hamilton and Madison in aggressively arguing in favor of the creation of a new and more powerful, centralized, but nonetheless balanced system of government. Writing under the shared pseudonym of "Publius," they articulated this vision in the Federalist Papers, a series of 85 articles, written in 1788 to persuade the citizenry to ratify the proposed Constitution of the United States. Jay wrote five of these articles: numbers 2, 3, 4, and 5 "Concerning Dangers from Foreign Force and Influence;" and number 64 on "The Powers of the Senate."

Jay's essays were shaped most powerfully by his training as a lawyer and his deep grasp of the importance of the figure of the lawgiver in the tradition of republican political thought. Jay combined such elements with a Christian aesthetic vision glorifying the idea of a national union, a rhetorical synthesis central to The Federalist's popular appeal in political debate.

The Jay Court, 1790-1795

In 1789, George Washington nominated Jay as the first Chief Justice of the United States. Serving from 1790-1795, Jay was instrumental in establishing the internal procedures of the Court and setting legal precedents. His most notable case was Chisholm v. Georgia (1793), in which Jay and the Court affirmed that some of the state's sovereignty was subordinate to the United States Constitution. Unfavorable reaction to the decision led to the adoption of the Eleventh Amendment which denied federal courts authority in suits against a state by citizens of a different state or by subjects or citizens of a foreign state.

However, Jay's decision set the groundwork for judicial activism under Chief Justice John Marshall in the early 1800s, whose work established that the courts are entitled to exercise judicial review, the power to strike down both state and federal laws that violate the Constitution.

The Jay Treaty

Relations with Britain verged on war in 1794. James Madison proposed a trade war, "A direct system of commercial hostility with Great Britain," assuming that Britain was so weakened by its war with France that it would agree to American terms and not declare war. Washington rejected that policy and—in collaboration with Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton—sent Jay as a special envoy to Great Britain to negotiate a new treaty. However, Jay remained Chief Justice. The main goals were to avert war with Britain, settle financial and boundary issues left over from the Revolution, open trading opportunities with British colonies in the Caribbean, and establish friendly relations with Britain as America's chief trading partner. Jay achieved those goals in the document known to history as the Jay Treaty. The British also achieved their main goal, which was to keep the United States neutral in the ongoing war between Britain and France.

Jay thought, and Washington agreed, that it was the best treaty he could negotiate, and Washington signed it. The Senate, however, would ratify it only if the British agreed to remove a provision restricting American shipment of cotton. When Washington consulted the British minister, it turned out that the British had no objection to removing the clause.

The Republicans denounced the treaty, but Jay, as Chief Justice, decided not to take part in the debates. Jay's failure to obtain compensation for slaves taken by the British during the Revolution was a major reason for the bitter Southern opposition. Jefferson and Madison, fearing a commercial alliance with aristocratic Britain might undercut republicanism, led the opposition. Jay became a convenient symbol for those opposed to the treaty, and he half-jokingly complained he could travel from Boston to Philadelphia at night, solely by the light of his burning effigies.

Washington put his prestige on the line behind the treaty, and Hamilton and the Federalists mobilized public opinion. The Senate ratified the treaty by a 20-10 vote, just enough to meet the two-thirds requirement. The treaty averted war, resolved the remaining issues of the Revolution, gave America control over its western lands, expanded trade, and brought a decade of peace and prosperous trade between American and the world's strongest naval power, Britain.

Governor of New York

While in Britain, Jay was elected governor of New York State as a Federalist. He resigned from the Supreme Court and served as governor until 1801. As Governor, he received a proposal from Hamilton to gerrymander New York for the Presidential election of that year. He noted on the letter: "Proposing a measure for party purposes which it would not become me to adopt," and filed it without replying. President John Adams later renominated him to the United States Supreme Court; the Senate quickly confirmed him, but he declined, citing his own poor health and the court's lack of "the energy, weight, and dignity which are essential to its affording due support to the national government."

The Federalists nominated Jay as governor again in 1801, but he declined and retired to the life of a gentleman farmer in Westchester County, New York. His home and part of his farm are now operated as the John Jay Homestead by the New York Department of Parks, Recreation, and Historic Preservation, and is located on New York state route 22 in Katonah, near Bedford.

Jay lived on for more than two and a half decades, dying at home on May 15, 1829. He was buried in a family plot on his son Peter's farm in Rye, New York.

Religion

An Anglican, Jay had been a warden (lay officer) of Trinity Church, New York since 1785. As Secretary for Foreign Affairs, he supported a proposal after the Revolution that the Archbishop of Canterbury approve the ordination of bishops for the Protestant Episcopal Church in America. Afterward, he continued to work as an active leader in the reconstitution of the Episcopal Church in the United States.

In New York, Jay argued unsuccessfully in the provincial convention for a prohibition against Catholics holding office. However, in February 1788, the New York legislature under Jay's guidance approved an act requiring officeholders to renounce all foreign authorities "in all matters ecclesiastical as well as civil," a law designed to discourage Catholics from holding public office, while not banning them outright.

Throughout his public career and in retirement Jay was active in various works of Christian philanthropy. Motivated by his faith, he became a leading advocate of manumission and the abolition of the slave trade.

Jay felt strongly about the role of Christianity in the life of the new nation. He declared:

- Providence has given to our people the choice of their rulers, and it is the duty, as well as the privilege and interest of our Christian nation to select and prefer Christians for their rulers. October 12, 1816

John Jay served as vice president of the American Bible Society in 1816 until his election as president of the organization in 1821. He then served as president until 1827. In accepting the position of president, he wrote, “They who regard these [bible] Societies as deriving their origin and success from the author and Giver of the Gospel cannot forbear concluding it to be the duty of Christians to promote the purposes for which they have been established; and that is particularly incumbent on their officers to be diligent in the business committed to them.”

An article in the October 1863 Bible Society Record describes Jay's tenure as president:

In all his duties, this useful, honoured, and excellent man observed great exactness, and this was the case especially with his domestic life. Every morning the whole family was summoned to religious worship, and precisely at nine in the evening the call was repeated, when he read them a chapter of God's Word, concluding the day with family prayer. Nothing ever interfered with these important and holy services.

Legacy

John Jay is remembered for his patriotism and service to his country. Although he was one of the most religious and politically conservative of the principal founders of America, he became an ardent supporter of the revolutionary cause and one of the leading exponents of the abolition of slavery. His eminence in public life included being a member and president of the Continental Congress, Chief Justice of New York State, diplomatic envoy, peace commissioner, Foreign Secretary of the United States, Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, and Governor of New York. Jay was also active in domestic and civil society as a dutiful son, faithful husband, and loving father. He was a vestryman in his local parish church, lay leader in the reformation of a Protestant denomination, president of the American Bible Society, and a founder and patron of the New York Manumission Society for the emancipation of African slaves. Jay's prominence as a statesman, churchman, citizen, and social reformer, driven by his dedication to the ideals of love and mercy, truth and justice, is his enduring legacy.

In 1787 and 1788, Jay collaborated with Alexander Hamilton and James Madison on the Federalist papers, thus contributing significantly to the political arguments and intellectual discourse that led to Constitution's ratification. Jay also played a key role in shepherding the Constitution through the New York State Ratification Convention in the face of vigorous opposition. In this battle, Jay relied not only on skillful political maneuvering, he also produced a pamphlet, An Address to the People of New York, that powerfully restated the Federalist case for the new Constitution.

In April 1794, Washington selected John Jay to negotiate a treaty with Great Britain aimed at resolving outstanding issues between the two nations. The resulting Treaty of Amity, Commerce and Navigation, commonly referred to as the Jay Treaty, was extremely controversial. Critics charged that it failed to address British impressment of American sailors or provide compensation for those slaves that the British had taken with them during the Revolutionary War. The Treaty's unpopularity played a significant role in the development of an organized opposition to the Federalists.

- John Jay's home today is a part of the Jay Heritage Center. It is also open as a museum.

- The Towns of Jay, Maine and Jay, New York and Jay, Vermont, and Jay County, Indiana are named after him. In 1964, the City University of New York's College of Police Science was officially renamed the John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

- Jay was named first among Columbia University's 250 Greatest Alumni by the Columbia Spectator. A large residence hall for undergraduates at Columbia is named for him, as well as the John Jay Award for alumni of Columbia College, and the John Jay Scholars program for exceptional students in the College. Columbia also has a John Jay professorship in classics.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Flanders, Henry. The Lives and Times of the Chief Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States: John Jay Through John Rutledge VI. Kessignger Publishing, 2006. ISBN 9781425497354

- Jay, William. The Life of John Jay: With Selections from His Correspondence and Miscellaneous Papers, Volume 1. Adamant Media Corporation, 2001. ISBN 9781402174018

- Johnson, Herbert A. John Jay: Colonial Lawyer. Beard Books, 1988. ISBN 9781587982705

- Stahr, Walter. John Jay: Founding Father. Hambledon & London, 2006. ISBN 9780826418791

External links

All links retrieved October 31, 2023.

- The Papers of John Jay Columbia University Libraries.

- John Jay History Channel.

- John Jay Oyez.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.