Huguenot

The term Huguenot refers to a member of the Protestant Reformed Church of France, historically known as the French Calvinists. Calvinism, and its related faith groups (including the Huguenots, Puritans, Presbyterians, and other Reformed Churches), represents the continuation of John Calvin’s unique interpretation of Christian theology. In addition to championing the supremacy of faith over works, Calvinism is most distinguished by two tenets: first, the doctrine of “life as religion” (which implies the sanctification of all aspects of human endeavor), and second, the doctrine of predestination, which claims that salvation is entirely predetermined by God.

Eight American Presidents (George Washington, Ulysses S. Grant, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Theodore Roosevelt, William Taft, Harry Truman, Gerald Ford and Lyndon Johnson) had significant proven Huguenot ancestry.[1] Additionally, Paul Revere senior was a Huguenot American colonist whose son, Paul Revere, became the famous United States revolutionary.

Etymology

Originally used as a term of derision, the origin of the name Huguenot remains uncertain. It may have been a French corruption of the German word Eidgenosse, meaning "a Confederate," perhaps in combination with a reference to the name Besançon Hugues (d 1532). In Geneva, Hugues was the leader of the "Confederate Party," so called because it favored an alliance between the city-state of Geneva and the Swiss Confederation. The label Huguenot was first applied in France to those conspirators involved in the Amboise plot of 1560: a foiled attempt to transfer power in France from the influential House of Guise, a move which would have had the side-effect of fostering relations with the Swiss. Thus, Hugues plus Eidgenosse becomes Huguenot. However, Roche writes that the term "Huguenot" is rather:

"a combination of a Flemish and a German word. In the Flemish corner of France, Bible students who gathered in each other's houses to study secretly were called Huis Genooten, or 'house fellows,' while on the Swiss and German borders they were termed Eid Genossen, or 'oath fellows,' that is, persons bound to each other by an oath. Gallicized into 'Huguenot,' often used deprecatingly, the word became, during two and a half centuries of terror and triumph, a badge of enduring honor and courage."[2]

Other scholars discredit dual linguistic origins, arguing that for the word to have spread into common use in France, it must have originated in the French language. The "Hugues hypothesis" argues that the name can be accounted for by connection with Hugues Capet king of France,[3] who reigned long before the Reform times, but was regarded by the Gallicans and Protestants as a noble man who respected people's dignity and lives. Janet Gray and other supporters of the theory suggest that the name huguenote would be roughly equivalent to little Hugos, or those who want Hugo.[3]

A derogatory etymology suggests an origin from the phrase, les guenon de Hus (the monkeys or apes of Jan Hus).[4]

Early history and beliefs

The availability of the Bible in local language was important to the spread of the Protestant movement and the development of the Reformed church in France, and the country had a long history of struggles with the papacy by the time the Protestant Reformation finally arrived. Around 1294, a French version of the Scriptures was prepared by the Catholic priest, Guyard de Moulin. The first known Provençal language translation of the Bible had been prepared by the twelfth century religious radical, Pierre de Vaux (Peter Waldo). Long after the sect was suppressed by the Roman Catholic Church, the remaining Waldensians sought to join William Farel and the Protestant Reformation, and Olivetan would publish a French Bible for them, but those who emerged from secrecy were eradicated by Francis I in 1545. A two-volume folio version of this translation appeared in Paris, in 1488.

Other predecessors of the Reformed church included the pro-reform and Gallican Roman Catholics, like Jacques Lefevre. The Gallicans briefly achieved independence for the French church, on the principle that the religion of France could not be controlled by the Bishop of Rome, a foreign power.[5] In the time of the Protestant Reformation, Lefevre, a professor at the University of Paris, prepared the way for the rapid dissemination of Lutheran ideas in France with the publication of his French translation of the New Testament in 1523, followed by the whole Bible in the French language, in 1528. William Farel was a student of Lefevre who went on to become a leader of the Swiss Reformation, establishing a Protestant government in Geneva. Jean Cauvin (John Calvin), another student at the University of Paris, also converted to Protestantism. The French Confession of 1559 shows a decidedly Calvinistic influence.[6] Sometime between 1550 and 1580, members of the Reformed church in France came to be commonly known as Huguenots.

Criticisms of Roman Catholic Church

Above all, Huguenots became known for their fiery criticisms of worship as performed in the Roman Catholic Church, in particular the focus on ritual and what seemed an obsession with death and the dead. They believed the ritual, images, saints, pilgrimages, prayers, and hierarchy of the Catholic Church did not help anyone toward redemption. They saw Christian faith as something to be expressed in a strict and godly life, in obedience to Biblical laws, out of gratitude for God's mercy.

Like other Protestants of the time, they felt that the Roman church needed radical cleansing of its impurities, and that the Pope represented a worldly kingdom, which sat in mocking tyranny over the things of God, and was ultimately doomed. Rhetoric like this became fiercer as events unfolded, and stirred up the hostility of the Catholic establishment.

Violently opposed to the Catholic Church, the Huguenots attacked images, monasticism, and church buildings. Most of the cities in which the Huguenots gained a hold saw iconoclast attacks, in which altars and images in churches, and sometimes the buildings themselves were torn down. The cities of Bourges, Montauban and Orleans saw substantial activity in this regard.

Reform and growth

Huguenots faced periodic persecution from the outset of the Reformation; but Francis I (reigned 1515–1547) initially protected them from Parlementary measures designed for their extermination. The Affair of the Placards of 1534 changed the king's posture toward the Huguenots: he stepped away from restraining persecution of the movement.

Huguenot numbers grew rapidly between 1555 and 1562, chiefly amongst the nobles and city-dwellers. During this time, their opponents first dubbed the Protestants Huguenots; but they called themselves reformés, or "Reformed." They organized their first national synod in 1558, in Paris.

By 1562, the estimated number of Huguenots had passed one million, concentrated mainly in the southern and central parts of the country. The Huguenots in France likely peaked in number at approximately two million, compared to approximately sixteen million Catholics during the same period.

In reaction to the growing Huguenot influence, and the aforementioned instances of Protestant zeal, Catholic violence against them grew, at the same time that concessions and edicts of toleration became more liberal.

In 1561, the Edict of Orléans, for example, declared an end to the persecution; and the Edict of Saint-Germain recognized them for the first time (January 17, 1562); but these measures disguised the growing strain of relations between Protestant and Catholic.

Civil wars

Tensions led to eight civil wars, interrupted by periods of relative calm, between 1562 and 1598. With each break in peace, the Huguenots' trust in the Catholic throne diminished, and the violence became more severe, and Protestant demands became grander, until a lasting cessation of open hostility finally occurred in 1598.

The wars gradually took on a dynastic character, developing into an extended feud between the Houses of Bourbon and Guise, both of which—in addition to holding rival religious views—staked a claim to the French throne. The crown, occupied by the House of Valois, generally supported the Catholic side, but on occasion switched over to the Protestant cause when politically expedient.

The French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion began with a massacre at Vassy on March 1, 1562, when 23[7] (some sympathetic sources say hundreds[8]) of the Huguenots were killed, and about 200 were wounded.

The Huguenots transformed themselves into a definitive political movement thereafter. Protestant preachers rallied a considerable army and a formidable cavalry, which came under the leadership of Admiral Gaspard de Coligny. Henry of Navarre and the House of Bourbon allied themselves to the Huguenots, adding wealth and holdings to the Protestant strength, which at its height grew to 60 fortified cities, and posed a serious threat to the Catholic crown and Paris over the next three decades.

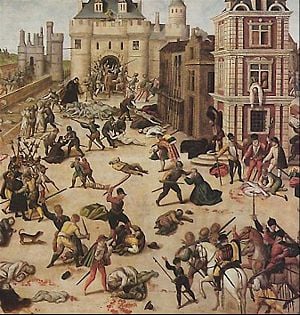

Saint Bartholomew's Day massacre

In what became known as the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre of 24 August – 17 September, 1572, Catholics killed thousands of Huguenots in Paris. Similar massacres took place in other towns in the weeks following, with death toll estimates again ranging wildly, from thousands to as high as 110,000. An amnesty granted in 1573 pardoned the perpetrators.

Edict of Nantes

The fifth war against the Huguenots began on February 23, 1574. The conflict continued periodically until 1598, when Henry of Navarre, having converted to Catholicism and become King of France as Henry IV, issued the Edict of Nantes. The Edict granted the Protestants equality with Catholics under the throne and a degree of religious and political freedom within their domains. The Edict simultaneously protected Catholic interests by discouraging the founding of new Protestant churches in the Catholic-controlled regions.

With the proclamation of the Edict of Nantes, and the subsequent protection of Huguenot rights, pressures to leave France abated, as did further attempts at colonization. However, under King Louis XIV (reigned 1643–1715), chief minister Cardinal Mazarin (who held real power during the king's minority up to his death in 1661) resumed persecution of the Protestants using soldiers to inflict dragonnades that made life so intolerable that many fled.

Edict of Fontainebleau

The king revoked the "irrevocable" Edict of Nantes in 1685 and declared Protestantism illegal with the Edict of Fontainebleau. After this, huge numbers of Huguenots (with estimates ranging from 200,000 to 1,000,000) fled to surrounding Protestant countries: England, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Norway, Denmark and Prussia—whose Calvinist Great Elector Friedrich Wilhelm I of Brandenburg] welcomed them to help rebuild his war-ravaged and underpopulated country. The Huguenot population of France had dropped to 856,000 by the mid 1660s, of which a plurality was rural. The greatest populations of surviving Huguenots resided in the regions of Basse-Guyenne, Saintonge-Aunis-Angoumois and Poitou.[9]

Huguenot Exodus from France

Early emigration

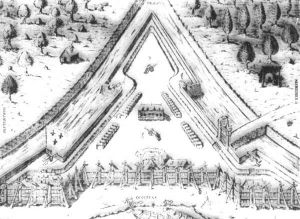

The first Huguenots to leave France seeking freedom from persecution had done so years earlier under the leadership of Jean Ribault in 1562. The group ended up establishing the small colony of Fort Caroline in 1564, on the banks of the St. Johns River, in what is today Jacksonville, Florida.

The colony was the first attempt at any permanent European settlement in the present-day United States, but the group survived only a short time. In September 1565, an attack against the new Spanish colony at St. Augustine backfired, and the Spanish wiped out the Fort Caroline garrison.

Settlement in South Africa

On December 31, 1687 a band of Huguenots set sail from France to the Dutch East India Company post at the Cape of Good Hope, South Africa. Individual Huguenots settled at the Cape of Good Hope from as early as 1671 with the arrival of Francois Villion (Viljoen) and an organized, large scale emigration of Huguenots to the Cape of Good Hope took place during 1688 and 1689. A notable example of this is the emigration of Huguenots from La Motte d'Aigues in Provence, France.

Many of these settlers chose as their home an area called Franschhoek, Dutch for French Corner, in the present day Western Cape province of South Africa. A large monument to commemorate the arrival of the Huguenots in South Africa was inaugurated on 7 April 1948 at Franschhoek.

Many of the farms in the Western Cape province in South Africa still bear French names and there are many families, today mostly Afrikaans speaking, whose surnames bear witness to their French Huguenot ancestry. Examples of these are: Blignaut, de Klerk (Le Clercq), de Villiers, Visagie (Visage), du Plessis, du Toit, Fourie, Fouche, Giliomee (Guilliaume), Hugo, Joubert, and Labuschagne (la Buscagne), le Roux, Malan, Malherbe, Marais, Theron, Jordaan (Jurdan) and Viljoen amongst others, which are all common surnames in present day South Africa.[10] The wine industry in South Africa owed a significant debt to the Huguenots, many of whom had vineyards in France.

Settlement in North America

Barred from settling in New France, many Huguenots moved instead to the Dutch colony New Netherland, which was later incorporated into New York and New Jersey, and to the 13 colonies of Great Britain in North America.

Huguenot immigrants founded New Paltz, New York. Another Huguenot settlement was established on the south shore of Staten Island, New York was founded by Daniel Perrin in 1692. The present day neighborhood of Huguenot was named after Perrin and these early settlers.

Some of the settlers chose the Virginia Colony, and formed communities in present-day Chesterfield County and at Manakintown, an abandoned Monacan village now located in Powhatan County about 20 miles west of downtown Richmond, Virginia, where their descendants continue to reside. On May 12, 1705, the Virginia General Assembly passed an act to naturalize the 148 Huguenots resident at Manakintown. [11]

Many Huguenots also settled in the area around the current site of Charleston, South Carolina. In 1685, Rev. Elie Prioleau from the town of Pons in France settled in what was then called Charlestown. He became pastor of the first Huguenot church in North America in that city.

Most of the Huguenot congregations in North America merged or affiliated with other Protestant denominations, such the Presbyterian Church (USA), United Church of Christ, Reformed Churches, and the Reformed Baptists.

Huguenots in America often married outside their immediate French Huguenot communities, leading to rapid assimilation. They made an enormous contribution to American economic life, especially as merchants and artisans in the late Colonial and early Federal periods. One outstanding contribution was the establishment of the Brandywine powder mills by E.I. du Pont, a former student of Lavoisier.

Asylum in the Netherlands

French Huguenots already fought alongside the Dutch and against Spain during the first years of the Dutch Revolt. The Dutch Republic became rapidly the exile haven of choice for Huguenots. Early ties were already visible in the Apologie of William the Silent, condemning the Spanish Inquisition and written by his court reverend Huguenot Pierre L'Oyseleur, Lord of Villiers.

Louise de Coligny, sister of murdered Huguenot leader Gaspard de Coligny had married the Calvinist Dutch revolt leader William the Silent. As both spoke French in everyday life, their court church in the Prinsenhof in Delft was providing French spoken Calvinist services, a practice still continued to today. The Prinsenhof is now one of the remaining 14 active Walloon churches of the Dutch Reformed Church.

These very early ties between Huguenots and the Dutch Republic's military and political leadership, the House of Orange-Nassau, explains the many early settlements of Huguenots in the Dutch Republic's colonies around Cape of Good Hope in South-Africa and the New Netherlands colony in America.

Stadtholder William III of Orange, who later became King of England, emerged as the strongest opponent of Louis XIV, after Louis' attack on the Dutch Republic in 1672. He formed the League of Augsburg as main opposition coalition. Consequently, many Huguenots saw the wealthy and Calvinist Dutch Republic as the most attractive country for exile after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes. They also found established many more French speaking Calvinist churches there.

The Dutch Republic received the largest group of Huguenot refugees with an estimated 75,000 to 100,000 Huguenots after the revocation of the Edict. Amongst them were 200 reverends. This was a huge influx, the entire population of the Dutch Republic amounted to ca. two million at that time. Around 1700, it is estimated that nearly 25 percent of the Amsterdam population was Huguenot. Amsterdam and the area of West-Frisia were the first areas providing full citizens rights to Huguenots in 1705, followed by the entire Dutch Republic in 1715. Huguenots married with Dutch from the outset.

One of the most prominent Huguenots refugees to the Netherlands was Pierre Bayle, who started teaching in Rotterdam, while publishing his multi-volume masterpiece Historical and Critical Dictionary. This composition became one of the one hundred foundational texts that formed the first collection of the U.S. Library of Congress.

Most Huguenot descendants in the Netherlands today are recognizable by French family names with typical Dutch surnames. Due to their early ties with the Dutch Revolt's leadership and even participation in the revolt, parts of the Dutch patriciate is of Huguenot descent. After 1815, when the Netherlands became a monarchy under the House of Orange-Nassau, some Huguenot patriciate families have been provided with an aristocratic predicate.

Asylum in Britain and Ireland

An estimated 50,000 Protestant Walloons and Huguenots fled to England, with about 10,000 moving on to Ireland. A leading Huguenot theologian and writer who led the exiled community in London, Andrew Lortie (born André Lortie), became known for articulating Huguenot criticism of the Holy See and transubstantiation.

Of these refugees, upon landing on the Kent coast, many gravitated towards Canterbury, then the county's hub, where many Walloon and Huguenot families were granted asylum. Edward VI granted them the whole of the Western crypt of Canterbury Cathedral for worship. This privilege in 1825 shrank to the south aisle and, in 1895, to the former chantry chapel of the Black Prince, where services are still held in French according to the reformed tradition every Sunday at 3pm. Other evidence of the Walloons and Huguenots in Canterbury includes a block of houses in Turnagain Lane where weavers' windows survive on the top floor, and 'the Weavers', a half-timbered house by the river. Many of the refugee community were weavers, but naturally some practiced other occupations necessary to sustain the community distinct from the indigenous population, this separation being a condition of their initial acceptance in the City. They also settled elsewhere in Kent, particularly Sandwich, Faversham and Maidstone - towns in which there used to be refugee churches.

Huguenot refugees flocked to Shoreditch, London in large numbers. They established a major weaving industry in and around Spitalfields, and in Wandsworth. The Old Truman Brewery, then known as the Black Eagle Brewery, appeared in 1724. The fleeing of Huguenot refugees from Tours, France had virtually wiped out the great silk mills they had built.

Many Huguenots settled in Ireland during the Plantations of Ireland. Huguenot regiments fought for William of Orange in the Williamite war in Ireland, for which they were rewarded with land grants and titles, many settling in Dublin.[12] Some of them took their skills to Ulster and assisted in the founding of the Irish linen industry.

Huguenots refugees found a safe haven in the Lutheran and Reformed states in Germany and Scandinavia. Nearly 44,000 Huguenots established themselves in Germany, and particularly in Prussia where many of their descendants rose to positions of prominence. Several congregations were founded, such as the Fredericia (Denmark), Berlin, Stockholm, Hamburg, Frankfurt, and Emden. Around 1700, a significant proportion of Berlin's population was of French mother tongue and the Berlin Huguenots preserved the French language in their religious service for nearly a century. They ultimately decided to switch to German in protest against the occupation of Prussia by Napoleon in 1806/1807.

Effects

The exodus of Huguenots from France created a kind of "brain drain" from which the kingdom did not fully recover for years. The French crown's refusal to allow Protestants to settle in New France was a factor behind that colony's slow population growth, which ultimately led to its conquest by the British by 1763. By the time of the French and Indian War, there may have been more people of French ancestry living in Britain's American colonies than there were in New France.

Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg invited Huguenots to settle in his realms, and a number of their descendants rose to positions of prominence in Prussia. The last Prime Minister of the (East) German Democratic Republic, Lothar de Maizière, is a scion of a Huguenot family.

The persecution and flight of the Huguenots greatly damaged the reputation of Louis XIV abroad, particularly in England; the two kingdoms, which had enjoyed peaceful relations prior to 1685, became bitter enemies and fought against each other in a series of wars from 1689 onward.

Persecution of Protestants continued in France after 1724, but ended in 1764 and the French Revolution of 1789 finally made them full-fledged citizens.

During the German occupation of France in the Second World War, a significant number of Protestants - not persecuted themselves - were active in hiding and saving Jews. Up to the present, many French Protestants, due to their history, feel a special sympathy for and tendency to support "The Underdog" in various situations and conflicts.

Notes

- ↑ Tommy Ingram, Huguenots for Newbies. Austin Genealogical Society. Retrieved July 22, 2008.

- ↑ Owen I.A. Roche. The Days of the Upright, A History of the Huguenots. (New York: C. N. Potter, 1965).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Janet G. Gray, "The Origin of the Word Huguenot," in Sixteenth Century Journal 14 (1983): 349-359.

- ↑ Association d'humanisme et renaissance. Bibliothèque d'humanisme et Renaissance. Travaux et documents. (Genève [etc.]: Librairie Droz, 1941. ISSN 00061999), 217.

- ↑ Margaret R. Miles. The Word Made Flesh A History of Christian Thought. (Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub, 2005. ISBN 1405108452), 381.

- ↑ Philip Schaff. The Creeds of Christendom With a History and Critical Notes. (New York: Harper, 1877. OCLC 2589524)

- ↑ New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia: Huguenots Retrieved July 15, 2008.

- ↑ Thomas M. Lindsay. A History of the Reformation. (New York: C. Scribner's Sons, 1906. OCLC 3960339), 190.

- ↑ Philip Benedict. The Huguenot Population of France, 1600-1685 The Demographic Fate and Customs of a Religious Minority. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, v. 81, pt. 5. (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1991. ISBN 0871698153)

- ↑ Bernard Lugan. Ces Français qui ont fait l'Afrique du Sud. Collection "Gestes." [Etrepilly]: Bartillat, 1996. ISBN 2841000869

- ↑ Virginia Naturalizations, 1657—1776.

- ↑ The Irish Pensioners of William III's Huguenot Regiments, Celticcousins.net. Retrieved July 22, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Baird, Charles Washington. History of the Huguenot Emigration to America. Baltimore: Genealogical Pub. Co, 1973. ISBN 0806305541

- Battles, Ford Lewis, and John Walchenbach. 2001. Analysis of the "Institutes of the Christian Religion" of John Calvin. P & R Publishing. ISBN 0875521827

- Benedict, Philip. The Huguenot Population of France, 1600-1685 The Demographic Fate and Customs of a Religious Minority. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, v. 81, pt. 5. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society, 1991. ISBN 0871698153

- Calvin, John. Institutes of the Christian Religion. Hendrickson Publishers, (1599 in Latin)1960. ISBN 0664220282

- Gray, Janet G. "The Origin of the Word Huguenot," in Sixteenth Century Journal 14 (1983): 349-359.

- Lindsay, Thomas M. A History of the Reformation. New York: C. Scribner's Sons, (original 1906) reprinted as A History Of The Reformation - The Reformation In Germany From Its Beginning To The Religious Peace Of Augsburg. London: Hesperides Press, 2006. ISBN 1406701041

- Lugan, Bernard. Ces Français qui ont fait l'Afrique du Sud. Collection "Gestes. [Etrepilly]: Bartillat, 1996. ISBN 2841000869

- McNeill, John Thomas. 1954. The History and Character of Calvinism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195007433

- Miles, Margaret R. The Word Made Flesh A History of Christian Thought. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub, 2005. ISBN 1405108452

- Purves, Andrew, and Charles Partee. Encountering God: Christian Faith in Turbulent Times. Nashville: Westminster Press, 2000. ISBN 0664222420

- Roche, Owen I. A. The Days of the Upright, A History of the Huguenots. New York: C. N. Potter, 1965.

- Schaff, Philip. The Creeds of Christendom With a History and Critical Notes. New York: Harper, 1877. OCLC 2589524.

- Wesley, John. 2001. Calvinism Calmly Considered. Salem, OH: Schmul Publishing Co. ISBN 0880194383

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.