Murder

Murder is the unlawful and intentional killing of one human being by another. The penalty for murder is usually life imprisonment, and in jurisdictions with capital punishment, the death penalty may be imposed. Murder is distinguished from other forms of homicide, such as manslaughter, by the intentions or malice of the perpetrator toward the victim. It is also distinguished from non-criminal homicides, such as the state-sanctioned execution of a criminal convicted of murder and the killing of another in self-defense.

While all religions regard murder as a sin, and all legal jurisdictions regard it as a crime, there continues to be dispute about whether all killings, including those that have been deemed "justifiable," should be regarded as wrong. For example, abortion and "fetal homicide" both involve the killing of an unborn fetus, one being legal in many jurisdictions while some might still consider it murder. Equally contentious is the question of capital punishment, with many arguing that lex talionis (based on "an eye for an eye, a life for a life") seriously violates human rights, specifically the most precious and irrevocable right—the right to life. In the ideal society, people should be able to recognize, based on their own conscience, that killing another human being constitutes undesirable, unacceptable behavior.

Definition

Murder is a homicide committed intentionally. As with most legal terms, the precise definition varies among jurisdictions. For example, in some parts of the United States anyone who commits a serious crime during which a person dies may be prosecuted for murder (see felony murder). Many jurisdictions recognize a distinction between murder and the less serious offense of manslaughter.

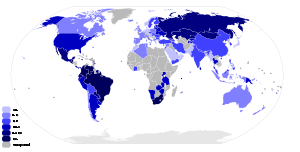

Murder demographics

Murder occurrences vary greatly among different countries and societies. In the Western world, murder rates in most countries have declined significantly during the twentieth century and are now between one to four cases per 100,000 people per year. Murder rates in Japan and Iceland are among the lowest in the world, around 0.5; the rate of the United States is among the highest among all developed countries, around 5.5, [1] with rates in major cities sometimes over 50 per 100,000.[2] Developing countries often have rates of 10-100 murders per 100,000 people per year.

Within the Western world, nearly 90 percent of all murders are committed by males, with males also being the victims of 74.6 percent of murders.[3] There is a sharp peak in the age distribution of murderers between the ages of 17 and 30. People become increasingly unlikely to commit a murder as they age. Incidents of children and adolescents committing murders are also extremely rare, notwithstanding the strong media coverage such cases receive.

Murder demographics are affected by the improvement of trauma care, leading to reduced lethality of violent assaults—thus the murder rate may not necessarily indicate the overall level of societal violence.[4]

Murder in law

Degrees of murder

Modern codifications tend to create a genus of offenses, known collectively as homicide, of which murder is the most serious species, followed by manslaughter which is less serious, and ending finally in justifiable homicide, which is not a crime at all.

Most countries have a number of different categories of murder, the qualifications and penalties for which differ greatly. These degrees vary according to who is killed, the motive of the murder, and the corresponding punishment. First degree murder is typically classified as deliberate and premeditated, while second degree murder is the deliberate killing of a victim without premeditation. Many states also have degrees reserved for the murder of police officers or other public officials.

Some countries, such as Canada, differentiate based on whether the murder was premeditated or if it was a heat of the moment act. Others, like Finland, Germany, and Romania, differentiate murder from manslaughter depending on whether or not there was particular cruelty, endangering of the public, if the murder was for pleasure or if it was intended to conceal another crime. Israel distinguishes between murderers who knew what they were doing versus those who were unaware of the consequences of their actions.

Depending on the determined degree of murder, some countries have a minimum length of prison sentence or automatically seek the death penalty.

Felony murder

The felony murder rule is a legal doctrine current in some common law countries that broadens the crime of murder in two ways. First, when a victim dies accidentally or without specific intent in the course of an applicable felony, it increases what might have been manslaughter (or even a simple tort) to murder. Second, it makes any participant in such a felony criminally responsible for any deaths that occur during or in furtherance of that felony. While there is some debate about the original scope of the rule, modern interpretations typically require that the felony be an obviously dangerous one, or one committed in an obviously dangerous manner. For this reason, the felony murder rule is often justified as a means of deterring dangerous felonies.

The concept of "felony murder" originates in the rule of transferred intent, which is older than the limit of legal memory. In its original form, the malicious intent inherent in the commission of any crime, however trivial, was considered to apply to any consequences of that crime, however unintended. Thus, in a classic example, a poacher shoots his arrow at a deer and hits a boy who was hiding in the bushes. Although he intended no harm to the boy, and did not even suspect his presence, the mens rea of the poaching is transferred to the actus reus of the killing.[5]

However, the actual situation is not as clear-cut as the above summary implies. In reality, not all felonious actions will apply in most jurisdictions. When the original felony contained no intent to kill there is dispute about the validity of transferring the malice and so invoking the charge of murder as opposed to manslaughter.[6] To qualify for the felony murder rule, the felony must present a foreseeable danger to life, and the link between the underlying felony and the death must not be too remote. Thus, if the receiver of a forged check has a fatal allergic reaction to the ink, most courts will not hold the forger guilty of murder. To counter the common law style interpretations of what does and does not merge with murder (and thus what does not and does qualify for felony murder), many jurisdictions explicitly list which offenses qualify. For example, the American Law Institute's Model Penal Code lists robbery, rape, arson, burglary, kidnapping, and felonious escape. Federal law specifies additional crimes, including terrorism and hijacking.

Defenses

Most countries allow conditions that "affect the balance of the mind" to be regarded as mitigating circumstances. This means that a person may be found guilty of "manslaughter" on the basis of "diminished responsibility" rather than murder, if it can be proved that the killer was suffering from a condition that affected their judgment at the time. Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and medication side-effects are examples of conditions that may be taken into account when assessing responsibility.

The defense of insanity may apply to a wide range of disorders including psychosis caused by schizophrenia, and excuse the person from the need to undergo the stress of a trial as to liability. In some jurisdictions, following the pre-trial hearing to determine the extent of the disorder, the verdict "not guilty by reason of insanity" may be used. Some countries, such as Canada, Italy, the United Kingdom, and Australia, allow post-partum depression (post-natal depression) as a defense against murder of a child by a mother, provided that a child is less than a year old (this may be the specific offense of infanticide rather than murder and include the effects of lactation and other aspects of post-natal care). Those who successfully argue a defense based on a mental disorder are usually referred to mandatory clinical treatment, rather than prison, until they are certified safe to be released back into the community.

Year-and-a-day rule

In some common law jurisdictions, a defendant accused of murder is not guilty if the victim survives for longer than one year and one day after the attack. This reflects the likelihood that if the victim dies, other factors will have contributed to the cause of death, breaking the chain of causation. Subject to any statute of limitations, the accused can still be charged with an offense representing the seriousness of the initial assault. However, with advances in modern medicine, most countries have abandoned a fixed time period and test causation on the facts of the case.

Murder of a fetus

Under the common law, if an assault on a pregnant woman resulted in a stillbirth, it was not considered murder; the child had to have breathed at least once to be murdered. Remedies were limited to criminal penalties for the assault on the woman, and a tort action for loss of the economic services of the eventual child and/or emotional pain and suffering. With the widespread adoption of laws against abortion, the assailant could of course be charged with that offense, but the penalty was often only a fine and a few days in jail.

When the United States Supreme Court greatly restricted laws prohibiting abortions in its famous Roe v. Wade decision (1973), even those sanctions became harder to use. This, among other factors, meant that a more brutal attack, ensuring that the baby died without breathing, would result in a lesser charge. Various states passed "fetal homicide" laws, making killing of an unborn child murder; the laws differ about the stage of development at which the child is protected. After several well-publicized cases, Congress passed the Unborn Victims of Violence Act, which specifically criminalizes harming a fetus, with the same penalties as for a similar attack upon a person, when the attack would be a federal offense. Most such attacks fall under state laws; for instance, Scott Peterson was convicted of murdering his unborn son as well as his wife under Californian pre-existing fetal homicide law.[7]

Murder and religion

The unlawful killing of another human is seen as evil and a sin in all of the world's major religions.[8]

Religions such as Hinduism and Buddhism espouse beliefs of absolute non-violence. The Hindu Laws of Manu state: He who commits murder must be considered as the worst offender, more wicked than a defamer, than a thief, and than he who injures with a staff" (Laws of Manu 8.345). The Buddhist Dhammapada says:

All tremble at the rod. All fear death. Comparing others with oneself, one should neither strike nor cause to strike.

All tremble at the rod. Life is dear to all. Comparing others with oneself, one should neither strike nor cause to strike.

Whoever, seeking his own happiness, harms with the rod other pleasure-loving beings, experiences no happiness hereafter.

Whoever, seeking his own happiness, harms not with the rod other pleasure-loving beings, experiences happiness hereafter (Dhammapada 129-32).

The Islamic Qur'an bars unjust killing: "And slay not the soul which God has forbidden except for the just cause…" (17:33) and "…If anyone killed a person not in retaliation for murder or to spread mischief in the land, it would be as if he killed the whole of mankind. And if anyone saved a life, it would be as if he saved the whole of mankind" (Surah Al-Maaida 5:32).[9]

In Judaism and Christianity, murder is banned in the Ten Commandments. Supporting this view is the passage in the Gospel of Matthew 26.51-52:

Then they came up and laid hands upon Jesus and seized him. And behold, one of those who were with Jesus stretched out his hand, and drew his sword, and struck the slave of the high priest, and cut off his ear. Then Jesus said to him, "Put your sword back into its place; for all who take the sword will perish by the sword." (Matthew 26.51-52)

In the Jewish Talmud is recorded:

"A man once came before Raba and said to him, "The ruler of my city has ordered me to kill a certain person, and if I refuse he will kill me." Raba told him, "Be killed and do not kill; do you think that your blood is redder than his? Perhaps his is redder than yours" (Talmud, Pesahim 25b).

Sun Myung Moon, founder of the Unification Church, has echoed this sentiment,

We could surmise that murdering an enemy whom all people, as well as yourself, dislike cannot be a crime. But even the hated man has the same cosmic value as you. Murdering is a crime, because by murdering a person you infringe upon a cosmic law (Sun Myung Moon, 9-30-1979).

Notes

- ↑ Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, Murder - Crime in the United States in 2004.

- ↑ Infoplease.com, Crime Rates for Selected Large Cities, 2003. Retrieved July 6, 2007.

- ↑ National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, Male Victims of Violence Facts. Retrieved June 13, 2007.

- ↑ Anthony R. Harris, Stephen H. Thomas, Gene A. Fisher, and David J. Hirsch, "Murder and medicine: the lethality of criminal assault 1960-1999" (2002). in Homicide studies Vol. 6, No. 2, 128-166. Retrieved January 8, 2006.

- ↑ Lawteacher.net, Explanation of Transferred Intent. Retrieved July 7, 2007.

- ↑ Prisons Foundation, Prisons Foundation objection to the rule.

- ↑ BBC News, US beach bodies killer convicted. Retrieved July 6, 2007.

- ↑ World Scripture, Murder. Retrieved July 4, 2007.

- ↑ Diane S. Dew Islam and Christianity (2001). Retrieved July 5, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Guyora, Binder. October 2004. "The Origins of American Felony Murder Rules." Stanford Law Review.

- Smith, J. C. and Brian Hogan. 1996. Smith & Hogan: Criminal Law. Virginia: Lexis Law Publishing. ISBN 0406081875

- United Kingdom Parliament. Lord Mustill on the Common Law concerning murder. Retrieved July 6, 2007.

- Wilson, Andrew (ed.). World Scripture: A Comparative Anthology of Sacred Texts. Paragon House, 1998. ISBN 978-1557787231

External links

All links retrieved June 2, 2025.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.