Turtle

| Turtles

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

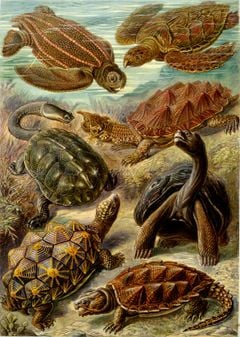

"Chelonia" from Ernst Haeckel's Kunstformen der Natur, 1904

| ||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||

| ||||||||

blue: sea turtles, black: land turtles

| ||||||||

|

Cryptodira |

Turtle is any aquatic or terrestrial reptile of the order Testudines (or Chelonia), characterized by toothless jaws with horny beaks and generally having a body shielded by a special bony or cartilagenous shell. Tortoise and terrapin are the names for two sub-groups commonly recognized within Testudines. Tortoise is the common name for any land-dwelling turtle, especially those belonging to the family Testudinidae. Terrapin is the common name for large freshwater or brackish water turtles belonging to the family Emydidae, especially the genus Malaclemys, and sometimes the genus Pseudemys (or Chrysemys).

As they advance their own survival and reproduction, turtles also play a vital role in food chains, both as herbivores and carnivores and as prey (particularly as vulnerable hatchlings). Their unique adaptations also provide unique aesthetic and practical values to human beings, with their shells collected as ornaments, and their behaviors (such as the new hatchlings making their way on the beach to the ocean) adding to human fascination with nature. Turtles have historically served as food or skinned for leather.

Not all turtles (also known technically as chelonians) have armor-like shells. The Trionychidae family has members commonly referred to as "softshell turtles," such as with the North American genus Apalone, because their carapace (outer, upper covering) lacks scutes (scales). The Australasian pig-nose turtle, Carettochelys insculpta, found in New Guinea and Australia and also known as the "plateless turtle," is a species of soft-shelled turtle whose gray carapace has a leathery texture. The leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea), found in all tropical and subtropical oceans, has a shell that lacks the bony scutes of other turtles, comprising mainly of connective tissue.

Turtles are found in most parts of the world, and there are about 300 species alive today. Turtles are ectothermic or cold-blooded, which means that their body temperature changes with their environment. They all breathe with lungs and, whether aquatic or terrestrial, reproduction involves laying eggs on land, including the highly aquatic sea turtles.

While turtles offer important ecological, commercial, and aesthetic values, and as a group have survived for millions of years, today many of the species are rare or endangered. This is largely due to anthropogenic factors, such as loss of habitat, pollution, and accidental catch in commercial fishing.

Anatomy and morphology

As reptiles, turtles are tetrapods (four-legged vertebrates) and amniotes (animals whose embryos are surrounded by an amniotic membrane that encases it in amniotic fluid.

Turtles vary widely in size, although marine turtles tend to be relatively bigger animals than their land and freshwater relatives.

The largest extant turtle is a marine turtle, the great leatherback sea turtle, which reaches a shell length of over 2.7 meters (8.8 feet) and weight of 900 kilograms (kg) (2,000 lb)—the world's fourth largest reptile, behind the larger crocodiles. Freshwater turtles are generally smaller, but with the largest species, the Asian softshell turtle Pelochelys cantorii, a few individuals have been reported to measure up to 200 centimeters (80 inches) (Das 1991). This dwarfs even the better-known alligator snapping turtle, the largest chelonian in North America, which attains a shell length of up to 80 centimeters (31½ inches) and a weight of about 60 kg (170 lb).

Giant tortoises of the genera Geochelone, Meiolania, and others were relatively widely distributed around the world into prehistoric times, and are known to have existed in North and South America, Australia, and Africa. They became extinct at the same time as the appearance of humans, and it is assumed that humans hunted them for food. The only surviving giant tortoises are on the Seychelles and Galápagos Islands and can grow to over 130 centimeters (50 inches) in length, and weigh about 300 kg (670 lb) (Connor 2007).

The largest known chelonian in the fossil record was Archelon ischyros, a Late Cretaceous sea turtle known to have been up to 4.6 meters (15 feet) long (Everhart 2007).

The smallest turtle is the speckled padloper tortoise of South Africa. It measures no more than 8 centimeters (3 inches) in length and weighs about 140 grams (5 ounces). Two other species of small turtles are the American mud turtles and musk turtles that live in an area that ranges from Canada to South America. The shell length of many species in this group is less than 13 centimeters (5 inches) in length.

Neck folding

Turtles are broken down into two groups, according to how they evolved a solution to the problem of withdrawing their neck into their shell. In most turtles, the Cryptodira, the neck is folding under their spine, being drawn directly back into the shell in an S-shaped curve. In the remainder, the Pleurodira, or side-necked turtles, the neck is tucked next to the shoulder. Ancestral turtles are believed to have not been able to retract their neck.

Head

Most turtles that spend most of their life on land have their eyes looking down at objects in front of them. Some aquatic turtles, such as snapping turtles and soft-shelled turtles, have eyes closer to the top of the head. These species of turtles can hide from predators in shallow water where they lie entirely submerged except for their eyes and nostrils.

Sea turtles possess glands near their eyes that produce salty tears that rid their body of excess salt taken in from the water they drink.

Turtles are thought to have exceptional night vision due to the unusually large amount of rod cells in their retinas. Normal daytime vision is marginal at best due to their color-blindness and poor visual acuity. In addition to daytime vision problems, turtles have very poor pursuit movement abilities, which are normally reserved for predators that hunt quick moving prey. However, carnivorous turtles can move their heads quickly to snap.

Turtles have a rigid, toothless beak. Turtles use their jaws to cut and chew food. Instead of teeth, the upper and lower jaws of the turtle are covered by horny ridges. Carnivorous turtles usually have knife-sharp ridges for slicing through their prey. Herbivorous turtles have serrated edged ridges that help them cut through tough plants. Turtles use their tongues to swallow food, but, unlike most reptiles, they cannot extend their tongues to catch food.

Shell

The upper shell or upper outer covering of a turtle is called the carapace. The lower shell that encases the belly is called the plastron. The carapace and plastron are joined together on the turtle's sides by bony structures called bridges.

The inner layer of a turtle's shell is made up of about 60 bones that include portions of the backbone and the ribs, meaning the turtle cannot crawl out of its shell.

In most turtles, the outer layer of the shell is covered by horny scales called scutes that are part of its outer skin, or epidermis. Scutes are made up of a fibrous protein called keratin that also makes up the scales of other reptiles. These scutes overlap the seams between the shell bones and add strength to the shell. Some turtles do not have horny scutes. For example, the leatherback sea turtle and the soft-shelled turtles have shells covered with leathery skin instead.

The shape of the shell gives helpful clues to how the turtle lives. Most tortoises have a large dome-shaped shell that makes it difficult for predators to crush the shell between their jaws. One of the few exceptions is the African pancake tortoise, which has a flat, flexible shell that allows it to hide in rock crevices. Most aquatic turtles have flat, streamlined shells, which aid in swimming and diving. American snapping turtles and musk turtles have small, cross-shaped plastrons that give them more efficient leg movement for walking along the bottom of ponds and streams.

The color of a turtle's shell may vary. Shells are commonly colored brown, black, or olive green. In some species, shells may have red, orange, yellow, or gray markings and these markings are often spots, lines, or irregular blotches. One of the most colorful turtles is the eastern painted turtle, which includes a yellow plastron and a black or olive shell with red markings around the rim.

Tortoises, being land-based, have rather heavy shells. In contrast, aquatic and soft-shelled turtles have lighter shells that help them avoid sinking in water and allow them to swim faster with more agility. These lighter shells have large spaces called fontanelles between the shell bones. The shell of a leatherback turtle is extremely light because they lack scutes and contain many fontanelles.

Skin and molting

The outer layer of the shell is part of theskin. Every scute (or plate) on the shell corresponds to a single modified scale. The remainder of the skin is composed of skin with much smaller scales, similar to the skin of other reptiles. Growth requires molting of a turtle's skin, although not the scutes.

Turtles, including terrapins, do not molt their skins all in one event, as snakes do, but continuously, in small pieces. When kept in aquaria, small sheets of dead skin can be seen in the water when it has been sloughed off, (often appearing to be a thin piece of plastic), and often when the animal deliberately rubs itself against a piece of wood or stone. Tortoises also shed skin, but a lot of dead skin is allowed to accumulate into thick knobs and plates that provide protection to parts of the body outside the shell.

The scutes on the shell are never molted, and, as they accumulate over time, the shell becomes thicker. By counting the rings formed by the stack of smaller, older scutes on top of the larger, newer ones, it is possible to estimate the age of a turtle, if you know how many scutes are produced in a year. This method is not very accurate, partly because growth rate is not constant, but also because some of the scutes eventually fall away from the shell.

Limbs

Terrestrial tortoises have short, sturdy feet. Tortoises are famous for moving slowly. In part this is because of their heavy, cumbersome shell. However, it also is a result of the relatively inefficient sprawling gait that they have, with the legs being bent, as with lizards rather than being straight and directly under the body, as is the case with mammals.

The amphibious turtles normally have limbs similar to those of tortoises except that the feet are webbed and often have long claws. These turtles swim using all four feet in a way similar to the dog paddle, with the feet on the left and right side of the body alternately providing thrust. Large turtles tend to swim less than smaller ones, and the very big species, such as alligator snapping turtles, hardly swim at all, preferring to simply walk along the bottom of the river or lake. As well as webbed feet, turtles also have very long claws, used to help them clamber onto riverbanks and floating logs, upon which they like to bask. Male turtles tend to have particularly long claws, and these appear to be used to stimulate the female while mating. While most turtles have webbed feet, a few turtles, such as the pig-nose turtles, have true flippers, with the digits being fused into paddles and the claws being relatively small. These species swim in the same way as sea turtles.

Sea turtles are almost entirely aquatic and instead of feet they have flippers. Sea turtles "fly" through the water, using the up-and-down motion of the front flippers to generate thrust; the back feet are not used for propulsion but may be used as rudders for steering. Compared with freshwater turtles, sea turtles have very limited mobility on land, and apart from the dash from the nest to the sea as hatchlings, male sea turtles normally never leave the sea. Females must come back onto land to lay eggs. They move very slowly and laboriously, dragging themselves forwards with their flippers. The back flippers are used to dig the burrow and then fill it back with sand once the eggs have been deposited.

Ecology and life history

Even though many spend large amounts of their lives underwater, all turtles are air-breathing reptiles, and must surface at regular intervals to refill their lungs with fresh air. They can also spend a lot of their lives on dry land.

Some species of Australian freshwater turtles have large cloacal cavities that are lined with many finger-like projections. These projections, called "papillae," have a rich blood supply, and serve to increase the surface area of the cloaca. The turtles can take up dissolved oxygen from the water using these papillae, in much the same way that fish use gills to respire.

Turtles lay eggs, like other reptiles, which are slightly soft and leathery. The eggs of the largest species are spherical, while the eggs of the rest are elongated. Their albumen is white and contains a different protein than do bird eggs, such that it will not coagulate when cooked. Turtle eggs prepared to eat consist mainly of yolk.

In some species, temperature determines whether an egg develops into a male or a female: a higher temperature causes a female, a lower temperature causes a male.

Turtles lay the eggs on land. Large numbers of eggs are deposited in holes dug into mud or sand. They are then covered and left to incubate by themselves. When the turtles hatch they squirm their way to the surface and make for the water. There are no known species wherein the mother cares for the young.

Sea turtles lay their eggs on dry sandy beaches, and are highly endangered largely as a result of beach development and overhunting.

Turtles can take many years to reach breeding age. Often turtles only breed every few years or more.

Researchers have recently discovered a turtle’s organs do not gradually break down or become less efficient over time, unlike most other animals. It was found that the liver, lungs, and kidneys of a centenarian turtle are virtually indistinguishable from those of its immature counterpart. This has inspired genetic researchers to begin examining the turtle genome for genes related to longevity.

Evolutionary history

The first turtles are believed to have existed in the early Triassic period of the Mesozoic era, about 200 million years ago. The Permian-Triassic mass extinction event preceded the Triassic, and laid the foundation for the dominance of dinosaurs.

The exact ancestry of turtles is disputed. It was believed that they are the only surviving branch of the ancient clade Anapsida, which includes groups such as procolophonoids, millerettids, protorothyrids, and pareiasaurs. The millerettids, protorothyrids, and pareiasaurs became extinct in the late Permian period and the procolophonoids during the Triassic (Laurin 1996). All anapsid skulls lack a temporal opening, while all other extant amniotes have openings near the temples (although in mammals, the hole has become the zygomatic arch). Turtles are believed by some to be surviving anapsids, indeed the only surviving anapsids, as they also share this skull structure.

However, this point has become contentious, with some arguing that turtles reverted to this primitive state in the process of improving their armor. That is, the anapsid-like turtle skull is not a function of anapsid descent. More recent phylogenetic studies with this in mind placed turtles firmly within diapsids (which possess a pair of holes in their skulls behind the eyes, along with a second pair located higher on the skull), slightly closer to Squamata than to Archosauria (Rieppel and DeBraga 1996).

Molecular studies have upheld this new phylogeny, though some place turtles closer to Archosauria (Zardoya and Meyer 1998). Re-analysis of prior phylogenies suggests that they classified turtles as anapsids both because they assumed this classification (most of them studying what sort of anapsid turtles are) and because they did not sample fossil and extant taxa broadly enough for constructing the cladogram.

There is now some consensus that Testudines diverged from other diapsids between 285 and 270 million years ago (McGeoch and Gatherer 2005).

The earliest known modern turtle is proganochelys (family Proganochelyidae), that lived about 215 million years ago (EL 2007). However, this species already had many advanced turtle traits, and thus probably had many millions of years of preceding "turtle" evolution and species in its ancestry. It did lack the ability to pull its head into its shell (and it had a long neck), and had a long, spiked tail ending in a club, implying an ancestry occupying a similar niche to the ankylosaurs (though, presumably, only parallel evolution). Its tracing to the Triassic makes turtles one of the oldest reptile groups, and a much more ancient group than the lizards and snakes. Others, citing genetic evidence, consider turtles, along with crocodiles, a more modern reptile group.

Turtle, tortoise, or terrapin?

The word "turtle" is widely used to describe all members of the order Testudines. However, it is also common to see certain members described as terrapins, tortoises, or sea turtles as well. Precisely how these alternative names are used, if at all, depends on the type of English being used.

- British English normally describes these reptiles as turtles if they live in the sea; terrapins if they live in fresh or brackish water; or tortoises if they live on land. However, there are exceptions to this where American or Australian common names are in wide use, as with the Fly River turtle.

- American English tends to use the word turtle for all species regardless of habitat, although tortoise may be used as a more precise term for any land-dwelling species. Oceanic species may be more specifically referred to as sea turtles. The name "terrapin" is strictly reserved for the brackish water diamondback terrapin, Malaclemys terrapin; the word terrapin in this case being derived from the Algonquian word for this animal.

- Australian English uses turtle for both the marine and freshwater species, but tortoise for the terrestrial species.

To avoid confusion, the word "chelonian" is popular among veterinarians, scientists, and conservationists working with these animals as a catch-all name for any member of the order Testudines. It is based on the Ancient Greek word χελώνη (chelone, modern Greek χελώνα), meaning tortoise.

Taxonomy

There are approximately 300 extant species of testudines, split into two suborders: Cryptodira (11 extant families, 74 genera, over 200 species) and Pleurodira (3 extant families, 16 genera, over 60 species). The distinction between these two suborders is based on the mode in which they cover their head and neck. The Pleurodirans, also called the side-necked turtles, have long necks, and fold them sideways to align them with the shell. The Cryptodirans pull their neck straight back to conceal their head within the shell. A third order, the Paracryptodirans, are extinct.

Suborder Paracryptodira (extinct)

Suborder Cryptodira

- Family Chelydridae (Snapping Turtles)

- Family Meiolaniidae (Horned turtle, extinct)

- Superfamily Chelonioidea (Sea Turtles)

- Family Protostegidae (extinct)

- Family Thalassemyidae (extinct)

- Family Toxochelyidae (extinct)

- Family Cheloniidae (Green Sea Turtles and relatives)

- Family Dermochelyidae (Leatherback Turtles)

- Superfamily Kinosternoidea

- Family Dermatemydidae (River Turtles)

- Family Kinosternidae (Mud Turtles)

- Family Platysternidae (Big-headed Turtles)

- Superfamily Testudinoidea

- Family Haichemydidae (extinct)

- Family Lindholmemydidae (extinct)

- Family Sinochelyidae (extinct)

- Family Emydidae (Pond Turtles/Box and Water Turtles)

- Family Geoemydidae (Asian River Turtles, Leaf and Roofed Turtles, Asian Box Turtles)

- Family Testudinidae (Tortoises)

- Superfamily Trionychoidea

- Family Adocidae (extinct)

- Family Carettochelyidae (Pignose Turtles)

- Family Trionychidae (Softshell Turtles)

Suborder Pleurodira

- Family Araripemydidae (extinct)

- Family Proterochersidae (extinct)

- Family Chelidae (Austro-American Sideneck Turtles)

- Superfamily Pelomedusoidea

- Family Bothremydidae (extinct)

- Family Pelomedusidae (Afro-American Sideneck Turtles)

- Family Podocnemididae (Madagascan Big-headed and American Sideneck River Turtles)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cogger, H. G., R. G. Zweifel, and D. Kirshner. 1998. Encyclopedia of Reptiles and Amphibians. San Diego, CA : Academic Press. ISBN 0121785602.

- Connor, M. J. 2007. California Turtle and Tortoise Club turtle trivia. California Turtle and Tortoise Club. Retrieved June 2, 2007.

- Enchanted Learning (EL). 2007. Archelon. Enchanted Learning. Retrieved June 2, 2007.

- Everhart, M. 2007. Marine turtles from the Western Interior Sea. Oceans of Kansas Paleontology. Retrieved June 2, 2007.

- Laurin, M. 1996. Introduction to Procolophonoidea: A Permo-Triassic group of anapsids. University of California Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved June 2, 2007.

- McGeoch, D. J., and D. Gatherer. 2005. Integrating reptilian herpesviruses into the family herpesviridae. J. Virol. 79(2): 725–731. Retrieved June 2, 2007.

- Pritchard, P. C. H. 1979. Encyclopedia of Turtles. Neptune, N.J., T.F.H. ISBN 0876669186.

- Rieppel, O., and M. DeBraga. 1996. Turtles as diapsid reptiles. Nature 384: 453-455.

- Zardoya, R., and A. Meyer. 1998. Complete mitochondrial genome suggests diapsid affinities of turtles. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 95(24): 14226-14231.

External links

All links retrieved May 2, 2023.

- Introduction to Testudines: The Turtles UC Berkeley Museum of Paleontology.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.