Crocodile

| Crocodilians

| ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

black: range of Crocodilia

| ||||||||||||

|

Crocodile is the common name for any species belonging to the reptile family Crocodylidae (order Crocodilia). The term also is used to refer to all members of the order Crocodilia, a group that includes the "true crocodiles" (family Crocodylidae), the alligators and caimans (family Alligatoridae), and the gharials (family Gavialidae), as well as the Crocodylomorpha, which includes prehistoric crocodile relatives and ancestors.

Crocodiles (both family and order) are large, primarily aquatic reptiles that are primarily found in tropical regions of Asia, the Americas, Africa, and Oceania, and occupy both freshwater and marine environments. They have a lizard-like form and swim and feed in the water, but breed on the land.

While advancing their own individual need for survival, maintenance, and reproduction, crocodiles also provide benefit for the ecosystem and for humans. Ecologically, they serve as apex predators, keeping prey populations in check. While the larger crocodiles can be very dangerous to human beings, crocodiles do provide commercial, nutritional, and aesthetic benefit. Their hide is tanned and used to make leather goods, and crocodile meat is considered a delicacy in many parts of the world. They also add to the human wonder and enjoyment of nature.

Order Crocodilia

Crocodilia is an order of large reptiles that appeared about 84 million years ago in the late Cretaceous period. The basic crocodilian body plan is a very successful one; modern species closely resemble their Cretaceous ancestors. Mammals, too, have adapted to this body plan at least once in history.

The standard vernacular term for this group is "crocodilians" rather than "crocodiles," but the latter term also is used in reference to this group. Crocodilian will be the term used here to refer to the members of the order.

Crocodilians are considered the closest living relatives of birds, as the two groups are believed to be the only survivors of the Archosauria (Goodisman 2002). Members of the crocodilian stem group, the clade Crurotarsi, appeared about 220 million years ago in the Triassic period and exhibited a wide diversity of forms during the Mesozoic era.

The group is often spelled Crocodylia for consistency with the genus Crocodylus Laurenti, 1768. However, Richard Owen used the -i- spelling when he published the name in 1842, so it is generally preferred in the scientific literature. The -i- spelling is also a more accurate Latinization of the Greek κροκόδειλος (krokodeilos, literally "pebble-worm," referring to the shape and texture of the animal). The crocodile gets its name from the Greeks who observed them in the Nile River. The Greeks called them krokodilos, a compound word from kroke, which means "pebbles" and drilos, which means "worm." To the Greeks, this "worm of the stones" was so named because of the crocodiles’ habit of basking in the sun on gravel-covered river banks.

Description

Crocodilians have a flexible semi-erect (semi-sprawled) posture. They can walk in low, sprawled "belly walk," or hold their legs more directly underneath them to perform the "high walk" (Britton 2001). Most other reptiles can only walk in a sprawled position, and chameleons are the only modern reptiles with a more erect posture than crocodilians. The semi-erect posture makes it possible for some species to gallop on land if necessary (Britton 2001). An Australian species can reach a speed of over 16 km/h while galloping on an irregular forest floor. Their ankle bones, or tarsi are highly modified. Modern crocodilian locomotion is not a primitive trait, but a specialization for their semi-aquatic lifestyle.

All crocodilians have, like Homo sapiens (humans), thecodont dentition (teeth set in bony sockets), but unlike mammals, they replace their teeth throughout life (though not in “extreme” old age). Juvenile crocodilians replace teeth with larger ones at a rate as high as 1 new tooth per socket every month. After reaching adult size in a few years, however, tooth replacement rates can slow to two years and even longer. Very old members of some species have been seen in an almost "edentulous" (toothless) state, after teeth have been broken and replacement slowed or ceased. The result of this is that a single crocodile can go through at least 3,000 teeth in its lifetime. Each tooth is hollow, and the new one is growing inside the old. In this way, a new tooth is ready once the old is lost.

Crocodilians have a secondary bony palate that enables them to breathe when partially submerged, even if the mouth is full of water. Their internal nostrils open in the back of their throat, where a special part of the tongue called the "palatal valve" closes off their respiratory system when they are underwater. This way they can open their mouths underwater without choking. Most reptiles lack a secondary palate, but some skinks (family Scincidae) have a bony secondary palate too, to varying degrees.

Crocodiles and gharials have modified salivary glands on their tongue (salt glands), which are used for excreting excess salt ions from their body. Alligators and caimans have them too, but here they are non-functioning. This indicates that at some point the common origin of the Crocodylia was adapted to saline/marine environments. This also explains their wide distribution across the continents (i.e. marine dispersal). Species like the saltwater crocodile (C. porosus) can survive protracted periods of time in the sea, and can hunt prey within this environment.

Crocodilians are often seen lying with their mouths open, a behavior called gaping. One of its functions is probably to cool them down, but since they also do this at night and when it is raining, it is possible that gaping has a social function too.

Internal organs

Crocodilians lack a vomeronasal organ (yet it is detectable in the embryo) and a urinary bladder.

Like mammals and birds, and unlike other reptiles, crocodiles have a four-chambered heart; however, unlike mammals, oxygenated and deoxygenated blood can be mixed because of the presence of the left aortic arch. The right ventricle has two arteries leaving it; a pulmonary artery, which goes to the lungs, and the left aortic arch, which goes to the body, or systemic circulation. There is also a hole, the foramen of Panizza, between the left and right aortic arches (Hicks 2002). Because the left aortic arch goes directly to the gut, the shunting of oxygen-depleted blood which is high in CO2 may serve to aid in creating stomach acid to assist in digesting bones from its prey (Farmer 2006).

They have alveoli in their lungs and a unique muscular attachment to the liver and viscera that acts as a piston to breathing, separating the thoracic and abdominal cavities (similar to the diaphragm of mammals). Although tegu lizards have a primitive proto-diaphragm, separating the pulmonary cavity from the visceral cavity and allowing greater lung inflation, this is considered to have a different evolutionary history.

Crocodilians are known to swallow stones, gastroliths ("stomach-stones"), which act as a ballast in addition to aiding post-digestion processing of their prey. The crocodilian stomach is divided into two chambers, the first one is described as being powerful and muscular, like a bird gizzard. This is where the gastroliths are found. The other stomach has the most acidic digestive system of any animal, and it can digest mostly everything from their prey; including bones, feathers, and horns.

The gender of the juvenile is determined by the incubation temperature. This means crocodilians do not have genetic sex determination (like us), but a form of environmental sex determination that is based upon temperature embryos undergo early in their development.

Sensory organs

Like all reptiles, crocodilians have a relatively small brain, but it is more advanced than in other reptiles. Among other things it has a true cerebral cortex.

As in many other aquatic or amphibian tetrapods, the eyes, ears, and nostrils are all located on the same plane. They see well during the day and may even have color vision, plus the eyes have a vertical, cat-like pupil that also gives them excellent night vision. The iris is silvery (light-reflecting layer of tapetum behind the retina greatly increases their ability to see in weak light), making their eyes glow in the dark. A third transparent eyelid, the nictitating membrane, protects their eyes underwater. However, they cannot focus underwater, meaning other senses are more important when submerged underwater.

While birds and most reptiles have a ring of bones around each eye that supports the eyeball (the sclerotic ring), the crocodiles lack these bones, just like mammals and snakes. The eardrums are located behind the eyes and are covered by a movable flap of skin. This flap closes, along with the nostrils and eyes, when they dive, preventing water from entering their external head openings. The middle ear cavity has a complex of bony air-filled passages and a branching eustachian tube. There is also a small muscle (which is also seen in geckos) next to or upon the stapes, the stapedius, which probably functions in the same way as the mammalian stapedius muscle does, dampening strong vibrations.

The upper and lower jaws are covered with sensory pits, seen as small, black speckles on the skin, the crocodile version of the lateral organ seen in fish and many amphibians. But they have a completely different origin. These pigmented nodules encase bundles of nerve fibers that respond to the slightest disturbance in surface water, detecting vibrations and small pressure changes in water, making it possible for them to detect prey, danger, and intruders even in total darkness. These sense organs are known as DPRs (Dermal Pressure Receptors). While alligators and caimans only have them on their jaws, crocodiles have similar organs on almost every scale on their body. The function of the DPRs on the jaws is clear, but it is still not quite clear what the organs on the rest of the body in crocodiles actually do. They are probably doing the same as the organs on their jaws, but it seems like they can do more than that, like assisting in chemical reception or even salinity detection.

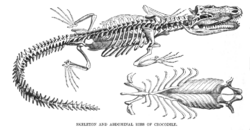

Skin and skeleton

The skin is covered with non-overlapping scales composed of the protein keratin (the same protein that forms hoofs, skin, horns, feathers, hair, claws, and nails in other tetrapods), which are shed individually. On the head, the skin is actually fused to the bones of the skull. There are small plates of bone, called osteoderms or scutes, under the scales. Just like a tree, crocodile osteoderms have annual growth rings, and by counting them it is possible to tell their age. Osteoderms are found especially on the back, and in some species also on the belly. The overlapping rows of scutes cover the crocodile's body from head to tail, forming a tough protective armor. Beneath the scales and osteoderms is another layer of armor, both strong and flexible and built of rows of bony overlapping shingles called osteoscutes, which are embedded in the animal's back tissue. The blood-rich bumpy scales seen on their backs act as solar panels.

The spool-shaped vertebrae in their ancestors went from being biconcave to having a concave front and a convex back in the modern forms. This made the vertebral column more flexible and strong, a useful adaptation when hunting in water.

They possess ribs of dermal origin restricted to the sides of the ventral body wall. The collar bone (clavicle) is absent.

Family Crocodylidae

| Crocodiles

| ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Nile Crocodile

| ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

See taxonomy. |

The family Crocodylidae comprises the "true crocodiles." These live throughout the tropics in Africa, Asia, the Americas, and Australia. Crocodiles tend to congregate in freshwater habitats like rivers, lakes, wetlands, and sometimes in brackish water. Some species, notably the saltwater crocodile of Australia, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific islands often live along the coastal areas. It is also known to venture far out to sea.

Crocodiles are more closely related to birds and dinosaurs than to most animals classified as reptiles, the three being included in the group Archosauria (“ruling reptiles”).

Crocodiles mostly feed on vertebrates like fish, reptiles, and mammals, and sometimes on invertebrates like mollusks and crustaceans, depending on species.

Their external morphology is a sign of their aquatic and predatory lifestyle. A crocodile’s physical traits allow it to be a successful predator. They have a streamlined body that enables them to swim faster. They also tuck their feet to their sides while swimming, which makes the animal even faster, by decreasing the water resistance. They have webbed feet which, although not used to propel the animal through the water, allow it to make fast turns and sudden moves in the water or initiate swimming. Webbed feet are an advantage in shallower water where the animals sometimes move around by walking.

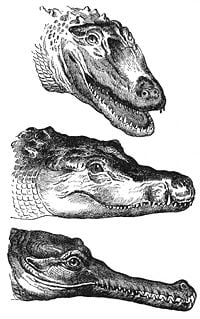

While often confused with each other, alligators and crocodiles belong to two quite separate taxonomic families, and are as distinct from one another as humans are from gorillas. As for appearance, one generally reliable rule is that alligators have U-shaped heads, while crocodiles are V-shaped—which can be remembered by noting that "A" in alligator comes before "C" in crocodile, and "U" comes before "V."

Crocodiles are very fast over short distances, even out of water. They have extremely powerful jaws capable of biting down with 3,000 pounds of pressure per square inch, and sharp teeth for tearing flesh, but cannot easily open their mouth if it is held closed. There are stories of people escaping from the long-snouted Nile crocodile by holding its jaws shut. Zoologists will often subdue crocodiles for study or transport by taping their jaws or holding their jaws shut with large rubber bands cut from automobile inner tubes. All large crocodiles also have sharp and powerful claws. They have limited lateral movement in their neck, so on land protection can be found by getting even a small tree between the crocodile's jaws and oneself.

Age and size

There is no reliable way of measuring crocodile age, although several techniques could be used to derive a reasonable guess. The most common method is to measure lamellar growth rings in bones and teeth—each ring corresponds to a change in growth rate, which typically occurs once a year between dry and wet seasons (Britton 2002).

Bearing these inaccuracies in mind, the oldest crocodilians appear to be the largest species. C. porosus is estimated to live around 70 years on average, and there is limited evidence that some individuals may exceed 100 years. One of the oldest crocodiles recorded died in a zoo in Russia apparently aged 115 years old (Britton 2002).

Size greatly varies between species, from the dwarf crocodile to the enormous saltwater crocodile. Large species can reach over 5 or 6 meters long and weigh well over 1200 kilograms (2,640 pounds). Despite their large adult size, crocodiles start their life at around 20 centimeters long. The largest species of crocodile is the saltwater crocodile, found in northern Australia and throughout Southeast Asia.

Biology and behavior

Crocodiles eat fish, birds, mammals, and occasionally smaller crocodiles.

Crocodiles are ambush hunters, waiting for fish or land animals to come close, then rushing out to attack. As cold-blooded predators, they can survive long periods without food, and rarely need to actively go hunting. The crocodile's bite strength is up to 3,000 pounds per square inch (psi), comparing to just 100 psi for a Labrador retriever, 350 psi for a large shark, or 800 psi for a hyena. Despite their slow appearance, crocodiles are top predators in their environment, and various species have been observed attacking and killing sharks. A famous exception is the Egyptian plover, a bird which is said to enjoy a mutually beneficial symbiotic relationship with the crocodile. According to reports, the plover feeds on parasites that infest the crocodile's mouth and the reptile will open its jaws and allow the bird to enter to clean out the mouth.

Crocodiles and humans

Wild crocodiles are protected in many parts of the world, but they also are farmed commercially. Their hide is tanned and used to make leather goods, such as shoes, wallets, briefcases, belts, hats, and handbags. Crocodile meat is also considered a delicacy in many parts of the world. The most commonly farmed species are the saltwater and Nile crocodiles, while a hybrid of the saltwater and the rare Siamese crocodile is also bred in Asian farms. Farming has resulted in an increase in the saltwater crocodile population in Australia, as eggs are usually harvested from the wild, so landowners have an incentive to conserve crocodile habitat.

Crocodile meat is consumed in some countries, such as Australia, Ethiopia, Thailand, South Africa, and also Cuba (in pickled form). It can also be found in specialty restaurants in some parts of the United States. The meat is white and its nutritional composition compares favorably with that of more traditional meats. It does tend to have a slightly higher cholesterol level than other meats. Crocodile meat has a delicate flavor and its taste can be complemented by the use of marinades. Choice cuts of meat include backstrap and tail fillet.

The larger species of crocodiles can be very dangerous to humans. Crocodiles are the leading cause of animal-related deaths as of 2001. The saltwater and Nile crocodiles are the most dangerous, killing hundreds of people each year in parts of Southeast Asia and Africa. Mugger crocodiles and possibly the endangered black caiman also are very dangerous to humans. American alligators are less aggressive and rarely assault humans without provocation.

The most deaths in a single crocodile attack incident may have occurred during the Battle of Ramree Island, on February 19, 1945, in what is now Myanmar. Nine hundred soldiers of an Imperial Japanese Army unit, in an attempt to retreat from the Royal Navy and rejoin a larger battalion of the Japanese infantry, crossed through ten miles of mangrove swamps that contained saltwater crocodiles. Twenty Japanese soldiers were captured alive by the British, and almost five hundred are known to have escaped Ramree. Many of the remainder may have been eaten by the crocodiles, although gunfire from the British troops was undoubtedly a contributory factor.

Taxonomy

Classification

- Superorder Crocodylomorpha

- Order Crocodilia

- Superfamily Gavialoidea

- Family Gavialidae – Gharials and false gharials

- Superfamily Alligatoroidea

- Family Alligatoridae

- Subfamily Diplocynodontinae (extinct)

- Subfamily Alligatorinae – Alligators

- Subfamily Caimaninae – Caimans

- Family Alligatoridae

- Superfamily Crocodyloidea

- Family Crocodylidae

- Subfamily Mekosuchinae (extinct)

- Subfamily Crocodylinae – Crocodiles

- Family Crocodylidae

- Superfamily Gavialoidea

- Order Crocodilia

Taxonomy of the family Crocodylidae

Most species in the family Crocodylidae are grouped into the genus Crocodylus. The two other living genera of this family are both monotypic: Osteolaemus and Tomistoma.

- Family Crocodylidae

- Subfamily Mekosuchinae (extinct)

- Subfamily Crocodylinae

- Genus Euthecodon (extinct)

- Genus Rimasuchus (extinct, formerly Crocodylus lloydi)

- Genus Osteolaemus

- Dwarf crocodile, Osteolaemus tetraspis (there has been controversy whether or not this is actually two species; current thinking is that there is one species with 2 subspecies: O. tetraspis tetraspis and O. t. osborni)

- Genus Crocodylus

- Crocodylus acutus, American crocodile

- Crocodylus cataphractus, Slender-snouted crocodile (Recent DNA studies suggest that this species may actually be more basal than Crocodylus, and belong in its own genus, Mecistops.)

- Crocodylus intermedius, Orinoco crocodile

- Crocodylus johnstoni, Freshwater crocodile

- Crocodylus mindorensis, Philippine crocodile

- Crocodylus moreletii, Morelet's crocodile or Mexican crocodile

- Crocodylus niloticus, Nile crocodile or African crocodile (the subspecies found in Madagascar is sometimes called the black crocodile)

- Crocodylus novaeguineae, New Guinea crocodile

- Crocodylus palustris, Mugger crocodile, marsh crocodile, or Indian crocodile

- Crocodylus porosus, Saltwater crocodile or estuarine crocodile

- Crocodylus rhombifer, Cuban crocodile

- Crocodylus siamensis, Siamese crocodile

- Subfamily Tomistominae (recent studies may show that this group is actually more closely related to the Gavialidae)

- Genus Kentisuchus (extinct)

- Genus Gavialosuchus (extinct)

- Genus Paratomistoma (extinct)

- Genus Thecachampsa (extinct)

- Genus Kentisuchus (extinct)

- Genus Rhamphosuchus (extinct)

- Genus Tomistoma

- Tomistoma schlegelii, False gharial or Malayan gharial

- Tomistoma lusitanica (extinct)

- Tomistoma cairense (extinct)

- Tomistoma machikanense (extinct; Pleistocene species from Japan)

- Sarcosuchus (extinct; also known as Super Croc)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Britton, A. 2001. Locomotion. Crocodilian Biology Database. Retrieved January 16, 2008.

- Britton, A. 2002. FAQ: How long do crocodiles live for? Crocodilian Biology Database. Retrieved January 16, 2008.

- Farmer, C. 2006. The role of left aortic blood flow in digestion in American alligators. American Physiological Society Conference, Abstract 21.5.

- Goodisman, D. 2002. Crocodilia. Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved January 16, 2008.

- Hicks, J. 2002. The physiological and evolutionary significance of cardiovascular shunting patterns in reptiles. News in Physiological Sciences 17: 241–245.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.