Cat

| Cat | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

|

Conservation status: Domesticated

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Felis catus Linnaeus, 1758 |

The cat (or domestic cat, house cat) (Felis catus) is a member of the Felidae family of the Carnivora order of the mammals.

The domesticated cat has been associated with humans for at least 9,500 years, and it is one of humankind's most popular pet animals. The numerous adaptations that allow it to be an effective predator of agricultural and household pests, such as rodents, also have made it valued in human society, and likewise is prized for the companionship and wonder it brings to people.

Characteristics

Domestic cats are considered to be descended from the wild cat Felis silvestris, which is found naturally over much of Europe, Asia, and Africa, and which is one of the smaller members of the cat family. It is thought that the original ancestor of the domestic cat is the African subspecies, Felis silvestris lybca (Nowak 1983).

Wild cats weigh about 3 to 8 kg (6 to 18 lbs) and domestic cats typically weigh between 2.5 and 7 kg (5.5 to 16 pounds); however, some breeds of domestic cat, such as the Maine coon, can exceed 11.3 kg (25 pounds). Some have been known to reach up to 23 kg (50 pounds) due to overfeeding. Conversely, very small cats (less than 1.8 kg / 4.0 lb) have been reported.

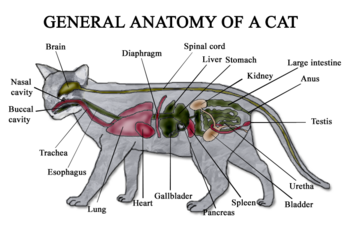

Like all members of the Felidae family, cats are specialized for a life of hunting other animals. Cats have highly specialized teeth and a digestive tract suitable to the digestion of meat. The premolar and first molar together compose the carnassial pair on each side of the mouth, which efficiently functions to shear meat like a pair of scissors. While this is present in canines, it is highly developed in felines. The cat's tongue has sharp spines, or papillae, useful for retaining and ripping flesh from a carcass. These papillae are small backward-facing hooks that contain keratin and assist in their grooming.

Cat senses are attuned for hunting. The senses of smell, hearing, and vision of cats are superior to those of humans. Cats' eyes have a reflective layer, which greatly improves their vision in dark conditions. They can not, however, see in total darkness (Siegal 2004). To aid with navigation and sensation, cats have dozens of movable vibrissae (whiskers) over their body, especially their face. Li (2005) reports that due to a mutation in an early cat ancestor, one of two genes necessary to taste sweetness has been lost by the cat family (Li 2005).

Thirty-two individual muscles in the ear allow for a manner of directional hearing; the cat can move each ear independently of the other. Because of this mobility, a cat can move its body in one direction and point its ears in another direction. Most cats have straight ears pointing upward. Unlike dogs, flap-eared breeds are extremely rare. (Scottish Folds are one such exceptional genetic mutation.) When angry or frightened, a cat will lay back its ears, to accompany the growling or hissing sounds it makes. Cats will also turn their ears back when they are playing or to listen to a sound coming from behind them. The angle of a cat's ears is an important clue to their mood.

Cats also possess rather loose skin; this enables them to turn and confront a predator or another cat in a fight, even when caught in a grip. The particularly loose skin at the back of the neck is known as the "scruff" and is the area by which a mother cat grips her kittens to carry them. As a result, cats have a tendency to relax and become quiet and passive when gripped there. This tendency often extends into adulthood and can be useful when attempting to treat or move an uncooperative cat. However, since an adult cat is quite a bit heavier than a kitten, a pet cat should never be carried by the scruff, but should instead have their weight supported at the rump and hind legs, and also at the chest and front paws. Often (much like a small child) a cat will lie with its head and front paws over a person's shoulder, and its back legs and rump supported under the person's arm.

Like almost all mammals, cats possess seven cervical vertebrae. They have thirteen thoracic vertebrae (compared to twelve in humans), seven lumbar vertebrae (compared to five in humans), three sacral vertebrae like most mammals (humans have five because of their bipedal posture), and twenty-two or twenty-three caudal vertebrae (humans have three to five, fused into an internal coccyx). The extra lumbar and thoracic vertebrae account for the cat's enhanced spinal mobility and flexibility, compared to humans; the caudal vertebrae form the tail, used by the cat for counterbalance to the body during quick movements (Zoolab 2007).

Cats, like dogs, are digitigrades: They walk directly on their toes, the bones of their feet making up the lower part of the visible leg. Cats are capable of walking very precisely, because like all felines they directly register; that is, they place each hind paw (almost) directly in the print of the corresponding forepaw, minimizing noise and visible tracks. This also provides sure footing for their hind paws when they navigate rough terrain.

Unlike dogs and most mammals, cats walk by moving both legs on one side and then both legs on the other. Most mammals move legs on alternate sides in sequence. Cats share this unusual gait with camels, giraffes, some horses (pacers), and a few other mammals.

Like all members of family Felidae except the cheetah, cats have retractable claws. In their normal, relaxed position, the claws are sheathed with the skin and fur around the toe pads. This keeps the claws sharp by preventing wear from contact with the ground and allows the silent stalking of prey. Cats can extend their claws voluntarily on one or more paws at will. They may extend their claws in hunting or self-defense, climbing, "kneading," or for extra traction on soft surfaces. It is also possible to make a cooperative cat extend its claws by carefully pressing both the top and bottom of the paw. The curved claws may become entangled in carpet or thick fabric, which may cause injury if the cat is unable to free itself.

Most cats have five claws on their front paws, and four or five on their rear paws. Because of an ancient mutation, however, domestic cats are prone to polydactyly, and may have six or seven toes. The fifth front claw (the dewclaw) is in a more proximal position than those of the other claws. More proximally, there is a protrusion that appears to be a sixth "finger." This special feature of the front paws, on the inside of the wrists, is the carpal pad, also found on the paws of dogs. It has no function in normal walking, but is thought to be an anti-skidding device used while jumping.

Metabolism

Cats conserve energy by sleeping more than most animals, especially as they grow older. Daily durations of sleep vary, usually 12–16 hours, with 13–14 being the average. Some cats can sleep as much as 20 hours in a 24-hour period. The term cat nap refers to the cat's ability to fall asleep (lightly) for a brief period and has entered the English lexicon—someone who nods off for a few minutes is said to be "taking a cat nap."

Due to their crepuscular nature, cats often are known to enter a period of increased activity and playfulness during the evening and early morning, dubbed the "evening crazies," "night crazies," "elevenses," or "mad half-hour" by some. The temperament of a cat can vary depending on the breed and socialization. Cats with "oriental" body types tend to be thinner and more active, while cats that have a "cobby" body type tend to be heavier and less active.

The normal body temperature of a cat is between 38 and 39°C (101 and 102.2°F). A cat is considered febrile (hyperthermic) if it has a temperature of 39.5°C (103°F) or greater, or hypothermic if less than 37.5°C (100°F). For comparison, humans have a normal temperature of approximately 36.8°C (98.6°F). A domestic cat's normal heart rate ranges from 140 to 220 beats per minute (bpm), and is largely dependent on how excited the cat is. For a cat at rest, the average heart rate should be between 150 and 180 bpm, about twice that of a human.

Cats enjoy heat and solar exposure, often sleeping in a sunny area during the heat of the day. Cats prefer warmer temperatures than humans do. People start to feel uncomfortable when their skin's temperature gets higher than about 44.5°C (112°F), but cats do not start to show signs of discomfort until their skin reaches about 52°C (126°F).

Being closely related to desert animals, cats can easily withstand the heat and cold of a temperate climate, but not for extended periods. Although certain breeds such as the Norwegian forest cat and Maine coon have developed heavier coats of fur than other cats, they have little resistance against moist cold (eg, fog, rain, and snow) and struggle to maintain their proper body temperature when wet.

Most cats dislike immersion in water; one major exception is the Turkish Van breed, also known as the swimming cat, which originated in the Lake Van area of Turkey and has an unusual fondness for water (Siegal 2004).

Domestication and relationship with humans

In 2004, a grave was excavated in Cyprus that contained the skeletons, laid close to one another, of both a human and a cat. The grave is estimated to be 9,500 years old. This is evidence that cats have been associating with humans for a long time (Pickrell 2004).

It is believed that wild cats chose to live in or near human settlements in order to hunt rodents that were feeding on crops and stored food and also to avoid other predators that avoid humans. It also is likely that wild cat kittens were sometimes found and brought home as pets. Naturalist Hans Kruuk observed people in northern Kenya doing just that. He also mentions that their domestic cats look just like the local wild cats (Kruuk 2002).

Like other domesticated animals, cats live in a mutualistic arrangement with humans. It is believed that the benefit of removing rats and mice from humans' food stores outweighed the trouble of extending the protection of a human settlement to a formerly wild animal, almost certainly for humans who had adopted a farming economy. Unlike the dog, which also hunts and kills rodents, the cat does not eat grains, fruits, or vegetables. A cat that is good at hunting rodents is referred to as a mouser. In Argentina, cats are used to kill vampire bats (Kruuk 2002).

The simile "like herding cats" refers to the seeming intractability of the ordinary house cat to training in anything, unlike dogs. Despite cohabitation in colonies, cats are lone hunters. It is no coincidence that cats are also "clean" animals; the chemistry of their saliva, expended during their frequent grooming, appears to be a natural deodorant. If so, the function of this cleanliness may be to decrease the chance a prey animal will notice the cat's presence. In contrast, dog's odor is an advantage in hunting, for a dog is a pack hunter; part of the pack stations itself upwind, and its odor drives prey towards the rest of the pack stationed downwind. This requires a cooperative effort, which in turn requires communications skills. No such communications skills are required of a lone hunter.

It is likely this lack of communication skills is part of the reason interacting with such an animal is problematic; cats in particular are labeled as opaque or inscrutable, if not obtuse, as well as aloof and self-sufficient. However, cats can be very affectionate towards their human companions, especially if they imprint on them at a very young age and are treated with consistent affection.

Human attitudes toward cats vary widely. Some people keep cats for companionship as pets. Others go to great lengths to pamper their cats, sometimes treating them as if they were children. When a cat bonds with its human guardian, the cat may, at times, display behaviors similar to that of a human. Such behavior may include a trip to the litter box before bedtime or snuggling up close to its companion in bed or on the sofa. Other such behavior includes mimicking sounds of the owner or using certain sounds the cat picks up from the human; sounds representing specific needs of the cat, which the owner would recognize, such as a specific tone of meow along with eye contact that may represent "I'm hungry." The cat may also be capable of learning to communicate with the human using non-spoken language or body language such as rubbing for affection (confirmation), facial expressions, and making eye contact with the owner if something needs to be addressed (e.g., finding a bug crawling on the floor for the owner to get rid of). Some owners like to train their cat to perform "tricks" commonly exhibited by dogs such as jumping, though this is rare.

Allergies to cat dander are one of the most common reasons people cite for disliking cats. However, in some instances, humans find the rewards of cat companionship outweigh the discomfort and problems associated with these allergies. Many choose to cope with cat allergies by taking prescription allergy medicine and bathing their cats frequently, since weekly bathing will eliminate about 90 percent of the cat dander present in the environment.

In rural areas, farms often have dozens of semi-feral cats. Hunting in the barns and the fields, they kill and eat rodents that would otherwise spoil large parts of the grain crop. Many pet cats successfully hunt and kill rabbits, rodents, birds, lizards, frogs, fish, and large insects by instinct, but might not eat their prey. They may even present their kills, dead or maimed, to their humans, perhaps expecting them to praise or reward them, or possibly even to complete the kill and eat the mouse. Others speculate that the behavior is a part of the odd relationship between human and cat, in which the cat is sometimes a "kitten" (playing, being picked up, and carried) and sometimes an adult (teaching these very large and peculiar human kittens how to hunt by demonstrating what the point of it all is).

Behavior

Social behavior

Many people characterize cats as "solitary" animals. Cats are highly social; a primary difference in social behavior between cats and dogs (to which they are often compared) is that cats do not have a social survival strategy, or a "pack mentality;" however, this only means that cats take care of their basic needs on their own (e.g., finding food, and defending themselves). This is not the same state as being asocial. One example of how domestic cats are "naturally" meant to behave is to observe feral domestic cats, which often live in colonies, but in which each individual basically looks after itself.

The domestic cat is social enough to form colonies, but does not hunt in groups as lions do. Some breeds like Bengal, Ocicat, and Manx are known to be very social. While each cat holds a distinct territory (sexually active males having the largest territories, and neutered cats having the smallest), there are "neutral" areas where cats watch and greet one another without territorial conflicts. Outside these neutral areas, territory holders usually aggressively chase away stranger cats, at first by staring, hissing, and growling, and if that does not work, by short but noisy and violent attacks. Fighting cats make themselves appear more impressive and threatening by raising their fur and arching their backs, thus increasing their visual size. Cats also behave this way while playing. Attacks usually comprise powerful slaps to the face and body with the forepaws as well as bites, but serious damage is rare; usually the loser runs away with little more than a few scratches to the face, and perhaps the ears. Cats will also throw themselves to the ground in a defensive posture to rake with their powerful hind legs.

Normally, serious negative effects will be limited to possible infections of the scratches and bites; though these have been known to sometimes kill cats if untreated. In addition, such fighting is believed to be the primary route of transmission of feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV). Sexually active males will usually be in many fights during their lives, and often have decidedly battered faces with obvious scars and cuts to the ears and nose. Not only males will fight; females will also fight over territory or to defend their kittens, and even neutered cats will defend their (smaller) territories aggressively.

Living with humans is a symbiotic social adaptation that has developed over thousands of years. The sort of social relationship cats have with their human keepers is hard to map onto more generalized wild cat behavior, but it is certain that the cat thinks of the human differently than it does other cats (i.e., it does not think of itself as human, nor that the human is a cat). This can be seen in the difference in body and vocal language it uses with the human, when compared to how it communicates with other cats in the household, for example. Some have suggested that, psychologically, the human keeper of a cat is a sort of surrogate for the cat's mother, and that adult domestic cats live forever in a kind of suspended kittenhood.

Fondness for heights

Most breeds of cat have a noted fondness for settling in high places, or perching. Animal behaviorists have posited a number of explanations, the most common being that height gives the cat a better observation point, allowing it to survey its "territory" and become aware of activities of people and other pets in the area. In the wild, a higher place may serve as a concealed site from which to hunt; domestic cats are known to strike prey by pouncing from such a perch as a tree branch, as does a leopard (Nash 2007).

If a cat falls, it can almost always right itself and land on its feet. This "righting reflex" is a natural instinct and is found even in newborn kittens (Siegal 2004).

This fondness for high spaces, however, can dangerously test the popular notion that a cat "always lands on its feet." The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals warns owners to safeguard the more dangerous perches in their homes, to avoid "high-rise syndrome," where an overconfident cat falls from an extreme height (Foster 2007).

Play

Domestic cats, especially young kittens, are known for their love of string play. Many cats cannot resist a dangling piece of string, or a piece of rope drawn randomly and enticingly across the floor. This well known love of string is often depicted in cartoons and photographs, which show kittens or cats playing with balls of yarn. It is probably related to hunting instincts, including the common practice of kittens hunting their mother's and each other's tails. If string is ingested, however, it can become caught in the cat’s stomach or intestines, causing illness, or in extreme cases, death. Due to possible complications caused by ingesting a string, string play is sometimes replaced with a laser pointer's dot, which some cats will chase. Some also discourage the use of laser pointers for pet play, however, because of the potential damage to sensitive eyes and/or the possible loss of satisfaction associated with the successful capture of an actual prey object, play or real. While caution is called for, there are no documented cases of feline eye damage from a laser pointer, and the combination of precision needed and low energy involved make it a remote risk. A common compromise is to use the laser pointer to draw the cat to a prepositioned toy so the cat gets a reward at the end of the chase.

Ecology

Feeding

Cats are highly specialized for hunting, compared to members of other carnivore families such as dogs and bears. This might be related to the cats' inability to taste sugars. Since they have a greatly reduced need to digest plants, their digestive tract has evolved to be shorter, too short for effective digestion of plants but less of a weight penalty for the rapid movement required for hunting. Hunting likewise has become central to their behavior patterns, even to their predilection for short bursts of intense exercise punctuating long periods of rest.

Like other members of the cat family, domestic cats are very effective predators. They ambush and immobilize vertebrate prey using tactics similar to those of leopards and tigers by pouncing; then they deliver a lethal neck bite with their long canine teeth that severs the victim's spinal cord, causes fatal bleeding by puncturing the carotid artery or the jugular vein, or asphyxiates it by crushing its trachea. The domestic cat hunts and eats over a thousand species, many of them invertebrates, especially insects.

Even well-fed domestic cats may hunt and kill birds, mice, rats, scorpions, cockroaches, grasshoppers, and other small animals in their environment. They often present such trophies to their owner. The motivation is not entirely clear, but friendly bonding behaviors are often associated with such an action. Ethologist Paul Leyhausen, in an extensive study of social and predatory behavior in domestic cats (documented in his book Cat Behavior), proposed a mechanism to explain this presenting behavior. In simple terms, cats adopt humans into their social group, and share excess kill with others in the group according to the local pecking order, in which humans place at or near the top. Another possibility is that presenting the kill might be a relic of a kitten feline behavior of demonstrating, for its mother's approval, that it has developed the necessary skill for hunting.

Reproduction

Female cats can come into heat several times a year. Males are attracted by the scent of the female's urine and by her calls and may fight with each other for the right to mate.

The gestation period for cats is approximately 63–65 days. The size of a litter averages three to five kittens, with the first litter usually smaller than subsequent litters. As in most carnivore young, newborn kittens are very small, blind, and helpless. They are cared for by their mother in a hidden nest or den that she prepares. Kittens are weaned at between six and seven weeks, and cats normally reach sexual maturity at 4–10 months (females) and to 5–7 months (males) (Voelker 1986, Siegal 2004).

Nomenclature

A group of cats is referred to as a clowder. A male cat is called a tom (or a gib, if neutered), and a female is called a queen. The male progenitor of a cat, especially a pedigreed cat, is its sire, and its female progenitor is its dam. An immature cat is called a kitten (which is also an alternative name for young rats, rabbits, hedgehogs, beavers, squirrels, and skunks). In medieval Britain, the word kitten was interchangeable with the word catling.

A cat whose ancestry is formally registered is called a pedigreed cat, purebred cat, or a show cat (although not all show cats are pedigreed or purebred). In strict terms, a purebred cat is one whose ancestry contains only individuals of the same breed. A pedigreed cat is one whose ancestry is recorded, but may have ancestors of different breeds (almost exclusively new breeds; cat registries are very strict about which breeds can be mated together). Cats of unrecorded mixed ancestry are referred to as domestic longhairs and domestic shorthairs or commonly as random-bred, moggies, mongrels, mutt-cats, or alley cats. The ratio of pedigree/purebred cats to random-bred cats varies from country to country. However, generally speaking, purebreds are less than ten percent of the total feline population (Richards 1999).

The word "cat" derives from Old English catt, which belongs to a group of related words in European languages, including Welsh cath, Spanish gato, Basque katu, Byzantine Greek κάττα, Old Irish cat, German Katze, and Old Church Slavonic kotka. The ultimate source of all these terms is unknown, although it may be linked to the ancient Nubian kadis and the Berber kadiska. The term puss (as in pussycat) may come from Dutch (from poes, a female cat, or the diminutive poesje, an endearing term for any cat) or from other Germanic languages.

History of cats and humans

Egypt

After associating with humans for several thousand years, cats entered the historical record in ancient Egypt. The first known painting of a cat dates to about 3,000 B.C.E. (Kruuk 2002).

Cats became very important in Egyptian society. They were associated with Bast, the goddess of the home, the domestic cat, protector of the fields and home from vermin infestations, and who sometimes took on the warlike aspect of a lioness. The first domesticated cats may have saved early Egyptians from many rodent infestations and likewise, Bast developed from the adoration for her feline companions. She was the daughter of the sun god Ra and played a significant role in Egyptian religion.

Cats were protected in Egypt and when they died their bodies were mummified. Some historians report that killing a cat was punishable by death and that when a family cat died family members would shave their eyebrows in mourning (Siegal 2002).

Roman and Medieval times

The Egyptians tried to prevent the export of cats from their country, but after Rome conquered Egypt in 30 B.C.E., pet cats became popular in Rome and were introduced throughout the Roman Empire (Nowak 1983).

Judaism considered the cat an unclean animal and cats are not mentioned in the Bible. As Christianity came to dominate European society, cats began to be looked on less favorably, often being thought to be associated with witchcraft. On some feast days, they were tortured and killed as a symbolic way of driving out the devil (Kruuk 2002).

Islam, however, looked at cats more favorably. It is said by some writers that Muhammad had a favorite cat, Muezza (Geyer 2004) It is said he loved cats so much that "he would do without his cloak rather than disturb one that was sleeping on it" (Reeves 2003).

During this time, pet cats also became popular over much of Asia. In different locations, distinct breeds of cats arose because of different environments and because of selection by humans. It is possible that interbreeding with local wild cats might have also played a part in this. Among the Asian cat breeds that developed this way are: The Persian, the Turkish Angora, the Siberian, and the Siamese (Siegal 2004). In Japan, the Maneki Neko is a small figurine of a cat that is thought to bring good fortune.

Modern times

In the Renaissance, Persian cats were brought to Italy and Turkish Angora cats were brought to France and then to England. Interest in different breeds of cats developed, especially among the wealthy. In 1871, the first cat exhibition was held in the Crystal Palace in London (Siegal 2004). Pet cats have continued to grow in popularity. It is estimated that 31 percent of United States households own at least one cat and the total number of pet cats in the United States is over 70 million (AVNA 2007).

Cats have also become very popular as subjects for paintings and as characters in children's books and cartoons.

Domesticated varieties

The list of cat breeds is quite large: Most cat registries recognize between 30 and 40 breeds of cats, and several more are in development, with one or more new breeds being recognized each year on average, having distinct features and heritage. The owners and breeders of show cats compete to see whose animal bears the closest resemblance to the "ideal" definition of the breed. Because of common crossbreeding in populated areas, many cats are simply identified as belonging to the homogeneous breeds of domestic longhair and domestic shorthair, depending on their type of fur.

Feral cats

Feral cats, domestic cats that have returned to the wild, are common throughout the world. In some places, especially islands that have no natural carnivores, they have been very destructive to native species of birds and other small animals. The Invasive Species Specialist Group has put the cat on its list of the "World's 100 Worst Invasive Species" (ISSG 2007).

The impacts of feral cats greatly depends on country or landmass. In the northern hemisphere, most landmasses have fauna adapted to wildcat species and other placental mammal predators. Here it may be argued that the potential for feral cats to cause damage is little unless cat numbers are very high, or the region supports unusually vulnerable native wildlife species. A notable exception is Hawaii, where feral cats have had extremely serious impacts on native birds species; "naive" fauna on islands of all sizes, in both hemispheres, are particularly vulnerable to feral cats.

In the southern hemisphere, there are many landmasses, including Australia, where cat species did not occur historically, and other placental mammal predators were rare or absent. Native species there are ecologically vulnerable and behaviorally "naive" to predation by feral cats. Feral cats have had extremely serious impacts on these wildlife species and have played a leading role in the endangerment and extinction of many of them. It is clear that in Australia, a large quantity of native birds, lizards, and small marsupials are taken every year by feral cats, and feral cats have played a role in driving some small marsupial species to extinction. Some organizations in Australia are now creating fenced islands of habitat for endangered species that are free of feral cats and foxes.

Feral cats may live alone, but most are found in large groups called feral colonies with communal nurseries, depending on resource availability. Some lost or abandoned pet cats succeed in joining these colonies, although animal welfare organizations note that few are able to survive long enough to become feral, most being killed by vehicles, or succumbing to starvation, predators, exposure, or disease. Most abandoned cats probably have little alternative to joining a feral colony. The average lifespan of such feral cats is much shorter than a domestic housecat, which can live sixteen years or more. Urban areas in the developed world are not friendly, nor adapted environments for cats; most domestic cats are descended from cats in desert climates and were distributed throughout the world by humans. Nevertheless, some feral cat colonies are found in large cities such as around the Colosseum and Forum Romanum in Rome.

Although cats are adaptable, feral felines are unable to thrive in extreme cold and heat, and with a very high protein requirement, few find adequate nutrition on their own in cities. They have little protection or understanding of the dangers from dogs, coyotes, and even automobiles. However, there are thousands of volunteers and organizations that trap these unadoptable feral felines, spay or neuter them, immunize the cats against rabies and feline leukemia, and treat them with long-lasting flea products. Before releasing them back into their feral colonies, the attending veterinarian often nips the tip off one ear to mark the feral as spayed/neutered and inoculated, since these cats will more than likely find themselves trapped again. Volunteers continue to feed and give care to these cats throughout their lives, and not only is their lifespan greatly increased, but behavior and nuisance problems, due to competition for food, are also greatly reduced. In time, if an entire colony is successfully spayed and neutered, no additional kittens are born and the feral colony disappears. Many hope to see an end to urban feral cat colonies through these efforts.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA). 2007. Market research statistics: Cat and dog ownership. American Veterinary Medical Association. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- Clutton-Brook, J. 1999. A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521634954

- Foster, R., and M. Smith. 2007. High-rise syndrome: Cats injured due to falls. PetEducation.com. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- Geyer, G. A. 2004. When Cats Reigned Like Kings: On the Trail of the Sacred Cats. Kansas City, MO: Andrews McMeel Publishing. ISBN 0740746979

- Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG). 2007. Felis catus. Invasive Species Specialist Group. Retrieved July 12, 2007.

- Kruuk, H. 2002. Hunter and Hunted: Relationships Between Carnivores and People. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521814103Ρ

- Li, X., W. Li, H. Wang, et al. 2005. Pseudogenization of a sweet-receptor gene accounts for cats' indifference toward sugar. PLOS Genetics. Retrieved July 17, 2007.

- Nash, H. 2007. Why do cats like high places? PetEducation.com. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- Nowak, R. M., and J. L. Paradiso. 1983. Walker's Mammals of the World. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801825253

- Pickrell, J. 2004. Oldest known pet cat? 9,500-year-old burial found on Cyprus. National Geographic News April 8, 2004. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- Reeves, M. 2003. Muhammad in Europe: A Thousand Years of Western Myth-Making. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0814775640

- Richards, J. 1999. ASPCA Complete Guide to Cats. New York: Chanticleer Press, Inc. ISBN 0811819299

- Siegal, M. (ed). 2004. The Cat Fanciers' Association Complete Cat Book. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0062702335

- Strain, G.M. n.d. How well do dogs and other animals hear?. Lousiana State University. Retrieved July 16, 2007.

- Voelker, W. 1986. The Natural History of Living Mammals. Medford, New Jersey: Plexus Publishing. ISBN 0937548081

- Wozencraft, W. C. 1992. Order Carnivora. In D. E. Wilson and D. M. Reeder (eds.), Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801882214

- Zoolab. 2002. Cat skeleton. ZooLab (BioWeb, University of Wisconsin).

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.