Skunk

| Skunks | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Striped skunk

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

Conepatus |

Skunk is the common name for any of the largely omnivorous mammals comprising the carnivore family Mephitidae, characterized by conspicuous patterns of black and white stripes and spots and well-developed anal scent glands used to produce noxious odors to deter threats. In a more specific sense, skunk can be used to refer to those members comprising the New World genera Mephitis, Conepatus, and Spilogale, with eleven extant species, while stink badger is the common name for members of the Old World genus Mydaus of Southeast Asia, with two extant species. Stink badgers only recently have been placed as part of the skunk clade. Skunks sometimes are referred to as polecats.

Skunks, as omnivores, play an important role in food chains and impact a variety of plant and animal life. They consume insects, rodents, bees, salamanders, leaves, grasses, fungi, and numerous other plant and animal matter, while being consumed by owls and larger carnivores, such as coyotes, foxes, lynx, civets, and pumas (Wund 2005). For humans, the consumption of pests such as insects and rodents is beneficial, and skunk furs are sometimes traded, while stink badgers sometimes are eaten as food after the sting glands are removed (Wund 2005).

Overview and description

Skunks were formerly considered to be a subfamily, Mephitinae, of the Mustelidae family of weasels and related animals. Some taxonomies still have the skunks within Mustelidae; however, generally they are now placed in their own family of Mephitidae. This placement is supported by genetic evidence indicating that they are not as closely related to the Mustelidae as formerly thought (Dragoo and Honeycutt 1997).

There are 13 species of skunks, which are divided into four genera: Mephitis (hooded and striped skunks, two species), Spilogale (spotted skunks, four species), Mydaus (stink badgers, two species), and Conepatus (hog-nosed skunks, five species). The two skunk species in the Mydaus genus inhabit Indonesia and the Philippines; all other skunks inhabit the Americas from Canada to central South America.

Extant mephitids tend to have a broad, squat body, a long rostra, short, well-muscled limbs, long and robust front claws, and a thickly-furred tail (Wund 2005). Skunk species vary in size from about 15.6 to 37 inches (40 to 70 centimeters) and in weight from about 1.1 pounds (0.5 kilograms) (the spotted skunks) to 18 pounds (8.2 kilograms) (the hog-nosed skunks).

Skunks are recognized by their striking color patterns, generally with a black or brown basic fur color and with a prominent, contrasting pattern of white fur on their backs, faces, or tails; commonly they have a white stripe running from the head, down the back to the tail, or white spots (Wund 2005). Although the most common fur color is black and white, some skunks are brown or gray, and a few are cream-colored. All skunks have contrasting stripes or spots, even from birth. They may have a single thick stripe across back and tail, two thinner stripes, or a series of white spots and broken stripes (in the case of the spotted skunk). Some also have stripes on their legs.

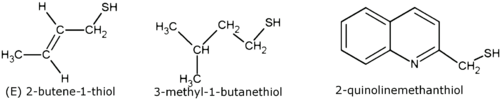

Members of Mephitidae are best known for their ability to excrete a strong, foul-smelling odor. All mephitids have scent glands that are well-developed and produce noxious odors to deter predators (Wund 2005). They are similar to, though much more developed than, the glands found in species of the Mustelidae family. Skunks have two glands, one on either side of the anus, that produce a mixture of sulfur-containing chemicals (methyl and butyl thiols (mercaptans)) that has a highly offensive smell that can be described as a combination of the odors of rotten eggs, garlic, and burnt rubber. Muscles located next to the scent glands allow them to spray with high accuracy as far as 2 to 5 meters (7 to 15 ft).

Skunk spray is composed mainly of low molecular weight thiol compounds, namely (E)-2-butene-1-thiol, 3-methyl-1-butanethiol, and 2-quinolinemethanethiol, as well as acetate thioesters of each of these (Wood et al. 2002; Wood 2008). These compounds are detectable at concentrations of about 2 parts per million (Helmenstine 2008).

Because of the singular, musk-spraying ability of the skunk, the names of the family and the most common genus (Mephitidae, Mephitis) mean "stench," and Spilogale putorius means "stinking spotted weasel." The word skunk is a corruption of an Abenaki name for them, segongw or segonku, which means "one who squirts" in the Algonquian dialect.

Behavior and diet

Skunks are crepuscular or nocturnal, and are solitary animals when not breeding, though in the colder parts of their range they may gather in communal dens for warmth. During the day, they shelter in burrows that they dig with their powerful front claws, or in other man-made or natural hollows as the opportunity arises. Both sexes occupy overlapping home ranges through the greater part of the year; typically 2 to 4 km² for females, up to 20 km² for males.

Skunks are omnivorous, eating both plant and animal material and changing their diet as the seasons change. They eat insects and larvae, earthworms, small rodents, lizards, salamanders, frogs, snakes, birds, moles, and eggs. They also commonly eat berries, roots, leaves, grasses, fungi, and nuts.

Less often, skunks may be found acting as scavengers, eating bird and rodent carcasses left by cats or other animals. In settled areas, skunks also seek human garbage. Pet owners, particularly those of cats, may experience a skunk finding its way into a garage or basement where pet food is kept.

Skunks are one of the primary predators of the honeybee, relying on their thick fur to protect them from stings. The skunk scratches at the front of the beehive and eats the guard bees that come out to investigate. Mother skunks are known to teach this to their young. A skunk family can virtually depopulate a healthy hive in just a few days.

Skunks tend to be gluttonous feeders. They gain weight quickly if their diet becomes too fatty.

Skunks do not hibernate in the winter. However, they do remain generally inactive and feed rarely. They often overwinter in a huddle of one male and multiple (as many as twelve) females. The same winter den is often repeatedly used.

Although they have excellent senses of smell and hearing—vital attributes in a crepuscular omnivore—they have poor vision. They cannot see objects more than about 3 meters away with any clarity, which makes them vulnerable to road traffic. Roughly half of all skunk deaths are caused by humans, as roadkill, or as a result of shooting and poisoning.

Reproduction and life cycle

Skunks typically mate in early spring and are a polygynous species, meaning that males usually mate with more than one female. Before giving birth, the female will excavate a den to house her litter. The gestation period varies with species. In members of Mephitis and Conepatus, the gestation period typically is from two to three months (Wund 2005). Spilogale gracilis exhibits delayed implantation, with the fertilized egg not implanting into the uterine wall for a prolonged period, and a total gestation time lasting 250 days or more; Spilogale putorius exhibits delayed implantation in the northern part of its range (Wund 2005).

There are from two to 10 young born per year in a single litter (Wund 2005). When born, skunk kits are altrical, being blind, deaf, and covered in a soft layer of fur. After one week, they can begin to use their stink glands in defense, but until that time rely on the mother (Wund 2005). About three weeks after birth, their eyes open. The kits are weaned about two months after birth, and begin foraging on their own, but generally stay with their mother until they are ready to mate, at about one year of age.

Skunks suffer high mortality from disease and predation, with about fifty to seventy percent dying in their first year (Wund 2005). Five to six years is the typical life span in the wild, although they can live up to seven years in the wild and up to ten years in captivity (Wund 2005).

Defense and anal scent glands

The notorious feature of skunks is their anal scent glands, which they can use as a defensive weapon. The odor of the fluid is strong enough to ward off bears and other potential attackers, and can be difficult to remove from clothing. They can spray some distance with great accuracy. The smell aside, the spray can cause irritation and even temporary blindness, and is sufficiently powerful to be detected by even an insensitive human nose anywhere up to a mile downwind. Their chemical defense, though unusual, is effective, as illustrated by this extract from Charles Darwin's Voyage of the Beagle (1839):

We saw also a couple of Zorrillos, or skunks—odious animals, which are far from uncommon. In general appearance the Zorrillo resembles a polecat, but it is rather larger, and much thicker in proportion. Conscious of its power, it roams by day about the open plain, and fears neither dog nor man. If a dog is urged to the attack, its courage is instantly checked by a few drops of the fetid oil, which brings on violent sickness and running at the nose. Whatever is once polluted by it, is for ever useless. Azara says the smell can be perceived at a league distant; more than once, when entering the harbour of Monte Video, the wind being off shore, we have perceived the odour on board the Beagle. Certain it is, that every animal most willingly makes room for the Zorrillo.

Skunks are reluctant to use their smelly weapon, as they carry just enough of the chemical for five or six uses—about 15 cc—and require some ten days to produce another supply. Their bold black and white coloring, however, serves to make the skunk's appearance memorable. Where practical, it is to a skunk's advantage to simply warn a threatening creature off without expending scent: The black and white warning color aside, threatened skunks will go through an elaborate routine of hisses, foot stamping, and tail-high threat postures before resorting to the spray. Interestingly, skunks will not spray other skunks (with the exception of males in the mating season); though they fight over den space in autumn, they do so with tooth and claw.

Most predatory animals of the Americas, such as wolves, foxes, and badgers, seldom attack skunks—presumably out of fear of being sprayed. The exception is the great horned owl, the animal's only serious predator, which, like most birds, has a poor-to-nonexistent sense of smell.

Skunks and humans

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recorded 1,494 cases of rabies in skunks in the United States for the year 2006—about 21.5 percent of reported cases in all species (Blanton et al. 2007). Skunks trail raccoons as vectors of rabies, although this varies regionally. (Raccoons dominate along the Atlantic coast and eastern Gulf of Mexico, skunks throughout the Midwest and down to the western Gulf, and in California.) Despite this prevalence, all recorded cases of human rabies from 1990 to 2002 are attributed by the CDC to dogs or bats.

Domesticated skunks can legally be kept as pets in the United Kingdom. However, the Animal Welfare Act 2006 has made it illegal to remove their scent glands (it is considered to be a cosmetic operation), thus making them impractical as pets.

The keeping of skunks as pets is legal only in certain states of the United States. Mephitis mephitis, the striped skunk species, is the most social skunk and the one most commonly domesticated. When the skunk is kept as a pet, the scent gland is removed. Typical life spans for domesticated skunks are considerably longer than for wild skunks, often reaching 10 years, though it is not unusual for a well cared skunk to live well past 20 years.

One problem with U.S. skunks kept as pets is genetic problems due to a lack of genetic diversity. The few breeders of skunks are using the same genetic stock (as none are allowed to be taken from the wild) that was available many decades ago, when skunks were bred for the fur trade instead of the pet trade. Many problems such as undescended testicles, epileptic seizures, and so forth are often found with the domestic stock.

Some skunks were reported by European settlers in America as being kept as pets by certain Native Americans. The Pilgrims are said to have kept skunks as pets (AUW 2008).

Classification

- Order Carnivora

- Family Canidae: Dogs, 35 species

- Family Ursidae: Bears, 8 species

- Family Procyonidae: Raccoons, 19 species

- Family Mustelidae: Weasels and allies, 55 species

- Family Ailuridae: Red pandas, 1 species

- Family Mephitidae

- Striped skunk, Mephitis mephitis

- Hooded skunk, Mephitis macroura

- Southern spotted skunk, Spilogale angustifrons

- Western spotted skunk, Spilogale gracilis

- Channel Islands spotted skunk, Spilogale gracilis amphiala

- Eastern spotted skunk, Spilogale putorius

- Pygmy spotted skunk, Spilogale pygmaea

- Western hog-nosed skunk, Conepatus mesoleucus

- Eastern hog-nosed skunk, Conepatus leuconotus

- Striped hog-nosed skunk, Conepatus semistriatus

- Andes skunk, Conepatus chinga

- Patagonian skunk, Conepatus humboldtii

- Indonesian or Javan stink badger (Teledu), Mydaus javanensis (sometimes included in Mustelidae)

- Palawan stink badger, Mydaus marchei (sometimes included in Mustelidae)

- Family Felidae: Cats, 37 species

- Family Viverridae: Civets and genets, 35 species

- Family Herpestidae: Mongooses, 35 species

- Family Hyaenidae: Hyenas, 4 species

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Arkansas Urban Wildlife (AUW). 2008. Skunk. Arkansas Urban Wildlife. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- Blanton, J. D., C. A. Hanlon, and C. E. Rupprecht. 2007. Rabies surveillance in the United States during 2006. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 231(4): 540-556. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- Darwin, C. 1839. Voyage of the Beagle. Penguin, 1989. ISBN 014043268X.

- Dragoo, J. W., and R. L. Honeycutt. 1997. Systematics of mustelid-like carnivores. Journal of Mammalology 78(2): 426–443.

- Helmenstine, A. M. 2008. What is the worst smelling chemical? About.com. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- Wilson, D. E., and D. M. Reeder. 2005. Mammal Species of the World. A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, 3rd edition. John Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801882214.

- Wood W. F., B. G. Sollers, G. A. Dragoo, and J. W. Dragoo. 2002. Volatile components in defensive spray of the hooked skunk, Mephitis macroura. Journal of Chemical Ecology 28(9): 1865. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- Wood, W. F. 1998. Chemistry of skunk spray. Dept. of Chemistry, Humboldt State University. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

- Wund, M. 2005a. Mephitidae. Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved September 09, 2008.

| ||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.