Salamander

| Salamanders

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Salamandra salamandra

| ||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

|

Salamander is the common term for any member of the order Caudata (also called Urodela) of the class Amphibia. Although lizard-like in external appearance, salamanders can be distinguished readily from the reptiles by the their lack of scales and claws. Salamanders can be differentiated from other amphibians (frogs and caecilians) by the presence of a tail in all larvae, juveniles, and adults, and by the fact that their forelimbs and hindlimbs typically are of about the same size (sirens lack hindlimbs) and are set at right angles to the body (Larson et al. 2006).

Salamanders characteristically have slender bodies, short legs, long tails, and moist, smooth skin, although rough-skinned species exist. The moist skin of the amphibians adapts them to habitats either near water or under some protection on moist ground, usually in a forest.

Salamanders not only provide benefit to their ecosystem through their role in food webs, but also provide benefit to humans beings. They help to control pest species, such as mosquitoes, are model organisms in medical and genetic research, and provide aesthetic benefits in art, literature, and simply through increasing the human enjoyment of nature.

Salamanders generally have a biphasic life cycle, typified by an aquatic larval stage with external gills and a terrestrial adult form that utilizes lungs or breathes through moist skin (Larson et al. 2006). However, some species are aquatic throughout life, not undergoing metamorphosis to a terrestrial, air-breathing adult, and some are terrestrial throughout life, hatching on land and lacking the larval aquatic stage. Furthermore, some aquatic forms lack gills and use lungs.

Overview

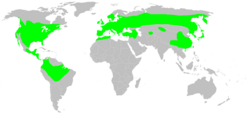

Salamanders are found in most moist or aqueous habitats in temperate regions of the northern hemisphere. Although salamander habitat is generally restricted to mostly the northern hemisphere, and to where there are moist and cool habitats, lungless salamanders (family Plethodontidae) are found in tropical areas of Central and South America (Larson et al. 2000). The greatest diversity is in North America, with representatives of 9 of the 10 living families (Larson et al. 2000). Although common on the European mainland, salamanders are not a native species of either Great Britain or Ireland. North American blind salamanders live in underground caves, wells, and streams.

Most salamanders are small, but some reach up to 5 feet (1.5 m) in length. The hellbender and the mudpuppy in North America can reach the length of a foot (30 cm) or more. In Japan and China, the giant salamander is found, which reaches 5 feet (1.5 m) and weighs up to 30 kilograms. There are references to an Andrias davidianus (giant salamander) in China that reaches a total body length of 1.8 to 2.0 m and a weight of 20~25 kg, with a record weight of over 100 kg claimed (GSPIW 2004), and Andrias japonicus in Japan that exceed 1.4 meters, and another one that lived for 51 years (GSPIW 2004b).

Salamanders are capable of regenerating lost limbs. The members of Plethodontidae (lungless salamanders) breath through the skin rather than utilize lungs. Among the salamanders that practice neoteny (those that do not undergo [metamorphosis]], but retain juvenile traits, but can reproduce) are included species in the families Sirenidae (sirens) and Protidae (mudpuppies), among others, including the species axolotl, which usually remains fully aquatic as it matures.

Salamanders are carnivores, eating insects and other arthropods, mollusks, worms, and sometimes aquatic crustaceans.

While amphibians are known as far back as the Devonian, and were diverse and common by the middle of the Carboniferous period, salamanders have been traced back only to the Middle Jurassic period, about 161 million years ago (Gianaro 2003). Prior to a 1996 discovery of numerous salamander fossils in Asia, the oldest such fossils were traced only to about 65 million years ago. The older fossil shows "extraordinary morphological similarity to its living relatives," and exhibits structures that "have remained little changed for more than 160 million years" (Gianaro 2003).

Distinguishing characteristics

In addition to approximately equal-sized limbs and the presence of a tail from the larval to adult stages, Larson et al. (2006) note a number of other featurs that distinguish salamanders from other amphibians:

- Absence of a middle ear and otic arch

- presence of ribs

- presence on both jaws of true teeth

- external gills and gill slits in aquatic larvae, when this stage is present

- absence of the following bones: postorbital, postpariental, tabular, jugal, supratemporal, suraoccipital, basioccipital, and ectoterygoid

Classification

Salamanders comprise the taxonomic order Urodela (or Caudata). Extant (living) salamanders are placed in ten families within this order, divided into three suborders:

Newts, which are placed in the family "Salamandridae," are small, usually bright-colored semiaquatic salamanders of North America, Europe, and Asia, distinguished from other salamanders by the lack of rib or costal grooves along the sides of the body

However, salamanders are known in the fossil record as far back as the Jurassic period. Larson et al. (2006) note one additional suborder (Karauroidea) and four additional families (Karauridae, Batrachosauroididae, Prosirenidae, and Scapherpetontidae—the last three placed in Aalamandroidea) known only from fossils.

Salamanders and humans

Salamanders have a long history interacting with human culture, being represented in mythology, legends, folklore, literature, and art.

Mythology and misunderstanding are linked to salamanders. Early travelers to China were shown garments supposedly woven from salamander wool; the cloth was completely unharmed by fire. The garments had actually been woven from asbestos. They are also tied to activities of witches, as noted in the Shakespeare reference to "eye of newt" being used as an ingredient by the three witches in Macbeth. Truly mythical salamanders have six legs and are highly valued by witches. "Lizards leg" is the hind left leg of one of these mythical beasts. The mythical salamander resembles the real salamander somewhat in appearance, but has six legs and makes its home in fires, the hotter the better. (Similarly, the salamander in heraldry is shown in flames, but is otherwise depicted as a generic lizard.)

Leonardo da Vinci wrote the following on the salamander: "This has no digestive organs, and gets no food but from the fire, in which it constantly renews its scaly skin. The salamander, which renews its scaly skin in the fire, for virtue."

Later, Paracelsus suggested that the salamander was the elemental of fire. These "fire salamander" myths likely originate in Europe from the fire salamander, Salamandra salamandra, which hibernates in and under rotting logs. When wood was brought indoors and put on the fire, the creatures mysteriously appeared from the flames. Because of this connection with fire, salamanders have often been associated with dragons.

Salamanders are popular objects in literature, having role in Karel Čapek´s science fiction novel War with the Salamanders (or War with the Newts), C.S. Lewis's fantasy book The Silver Chair, in the Harry Potter series, in Ray Bradbury's book, Fahrenheit 451, and other books. They are likewise featured in artwork, and video games.

Salamanders provide great benefit to humans, consuming mosquito larvae and helping to control other insect and pest populations. They are model organisms in a variety of research areas related to human health and disease, including limb regeneration, and are a source of compounds of medicinal value. They are important in food webs.

However, salamanders are facing threats from habitat loss, pollution, over-collecting, and introduction of invasive species. Many are sensitive to pollution.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Gianaro, C. 2003. New salamander species provide new answers to old questions in evolution. The University of Chicago Chronicle 22(13). Retrieved March 30, 2007.

- Giant Salamander Protection International Website (GSPIW). 2004a. Outline of Global Giant Salamanders Resources. Giant Salamander Protection International Website. Retrieved March 30, 2007.

- Giant Salamander Protection International Website (GSPIW). 2004b. 2004 b. Japanese Giant Salamander. Giant Salamander Protection International Website. Retrieved March 30, 2007.

- Larson, A., D. Wake, and T. Devitt, Tom. 2006. Caudata: Salamanders. Version 05. The Tree of Life Web Project.

- San Mauro, D., M. Vences, M. Alcobendas, R. Zardoya, and A. Meyer. 2005. Initial diversification of living amphibians predated the breakup of Pangaea. American Naturalist 165: 590-599. Retrieved March 30, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.