Coyote

| Coyote[1] | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Canis latrans Say, 1823 | ||||||||||||||

Modern range of Canis latrans

|

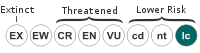

Coyote is the common name for a New World canine, Canis latrans, that resembles a small wolf or medium-sized dog and is characterized by a narrow, pointed snout, grayish brown to yellowish gray fur on the upper parts and buff or white colored fur below, reddish brown forelegs, and a bushy, black-tipped, tail. Also known as prairie wolf, the coyote is native to western North America, but now extends throughout North and Central America, ranging in the north from Alaska and all but the northernmost parts of Canada, south through the continental United States and Mexico, and throughout Central America to Panama (Tokar 2001). There are currently 19 recognized subspecies, with 16 in Canada, Mexico, and the United States, and three in Central America (Postanowicz 2008).

Mainly carnivores, who hunt largely in pairs, coyotes also supplement their diet with some plant matter and scavenge as well. As top carnivores, they help control populations of animals such as rodents, rabbits, and squirrels, and also consume birds, snakes, invertebrates (such as large insects), and even deer (which they may hunt in packs). As such, they play a vital role in food chains.

However, coyotes also hunt livestock and, thus, they have been a frequent target of land and aerial hunting, trapping, and poisoning. In the twentieth century, an estimated 20 million coyotes were killed by livestock ranchers, government bounty hunters, and others (Nash 2003). Yet, despite being extensively hunted, the coyote is one of the few medium-to-large-sized animals that actually has enlarged its range since human encroachment began. They are remarkably adaptable mammals, and reflect the reality that humans often cannot control nature as they desire (Nash 2003). They also provide a valuable service in controlling pest populations and filling a niche abandoned by the loss of larger predators, particularly wolves.

Unlike the gray wolf, which is Eurasian in origin, the coyote evolved in North America about two million years ago, alongside the dire wolf. Some believe the North American origin may account for their greater adaptability than the wolf, due to North America's greater prehistoric predation pressures (Geist 2007).

Description

Coyotes are members of the Canidae family within the order Carnivora. This family, whose members are called canids, is divided into the "true dog" (or canines) of the tribe Canini and the "foxes" of the tribe Vulpini. The coyote is a member of the Canini along with jackals, gray wolf, domestic dog, and so forth.

The color of the coyote's pelt varies from grayish brown to yellowish gray on the upper parts, while the throat and belly tend to have a buff or white color. The forelegs, sides of the head, muzzle, and feet are reddish brown. The back has tawny-colored underfur and long, black-tipped guard hairs that form a black dorsal stripe and a dark cross on the shoulder area. The black-tipped tail has a scent gland located on its dorsal base. Coyotes shed once a year, beginning in May with light hair loss, ending in July after heavy shedding. Mountain dwelling coyotes tend to be dark furred while desert coyotes tend to be more yellowish in color (Postanowicz 2008).

The feet are relatively small in relation to the rest of the body and the ears are proportionately large in relation to the head (Tokar 2001). As with other canids, coyotes are digitigrade, meaning that they walk on their toes. Their claws are blunt and help give them traction in running but are not used to capture prey. During pursuit, a coyote may reach speeds up to 43 mph (69 kph) (AMNH and Doherty), and can jump over 4 meters (13⅛ feet) (Tokar 2001). The upper frequency limit of hearing for coyotes is 80 kHZ, compared to the 60 kHz of domestic dogs (Mech and Boitani 2003).

Coyotes typically grow from 75 to 87 centimeters (30–34 inches) in length and, on average, weigh from 7 to 21 kilograms (15–46 pounds) (Tokar 2001). Northern coyotes are typically larger than southern subspecies, with one of the larger coyotes on record weighing almost 75 pounds (33.7 kilograms) and measuring over five feet in total length (Rible 2006).

The coyote's dental formula is I 3/3, C 1/1, Pm 4/4, M usually 2/3 or 2/2 (occasionally 3/3 or 3/2), which times two means 40, 42, or 44 teeth (Davis and Schmidly 1994; Schwartz and Schwartz 2001); usually they have 42 teeth (Schwartz and Schwartz 2001). Normal spacing between the upper canine teeth is 1⅛ to 1⅜ inches (29 to 35 millimeters) and 1 to 1¼ inches (25 to 32 millimeters) between the lower canine teeth (Wade and Bowns 1997).

Unlike wolves, but similarly to domestic dogs, coyotes have sweat glands on their paw pads. This trait is however absent in the large New England coyotes, which are thought to have some wolf ancestry (Coppinger and Coppinger 2001).

The name "coyote" is borrowed from Mexican Spanish, ultimately derived from the Nahuatl word coyotl (pronounced co-llo-tlh). Its scientific name, Canis latrans, means "barking dog."

Range

The coyote's pre-Columbian range was limited to the south-west and plains regions of the U.S. and Canada, and northern and central Mexico. By the nineteenth century, the species expanded north and west, expanding further after 1900, coinciding with land conversion and the extirpation of wolves. By this time, its range encompassed all of the U.S. and Mexico, southward into Central America, and northward into most of Canada and Alaska. This expansion is ongoing, and the species now occupies the majority of areas between 8°N (Panama) and 70°N (northern Alaska).

Although it was once widely believed that coyotes are recent immigrants to southern Mexico and Central America, aided in their expansion by deforestation, Pleistocene-Early Holocene records, as well as records from the Pre-Columbian period and early European colonization show that the animal was present in the area long before modern times. Nevertheless, range expansion did occur south of Costa Rica during the late 1970s and northern Panama in the early 1980s, following the expansion of cattle grazing lands into tropical rainforests.

Behavior

Coyotes are primarily nocturnal, but can occasionally be seen during daylight hours (Tokar 2001). Coyotes were once considered to be essentially diurnal, but have adapted to more nocturnal behavior with pressure from humans (McClennen et al. 2001).

Though coyotes have been observed to travel in large groups, they primarily live and hunt in pairs. They sometimes will hunt larger animals in packs. When there are packs, the typically consist of six closely related adults, yearlings, and young. Coyote packs are generally smaller than wolf packs and associations between individuals are less stable. It has been theorized that this is due to an earlier expression of aggression, and the fact that coyotes reach their full growth in their first year, unlike wolves who reach it in their second (Macdonald 1984). Common names of coyote groups are a band, a pack, or a rout.

Coyotes are capable of digging their own burrows, though they often appropriate the burrows of woodchucks or American badgers. They also may make dens in crevices of rocks or under tree roots. Coyote territorial ranges can be as much as 19 kilometers in diameter around the den and travel occurs along fixed trails (Tokar 2001).

In areas where wolves have been exterminated, coyotes usually flourish. For example, as New England became increasingly settled and the resident wolves were eliminated, the coyote population increased, filling the empty biological niche. Coyotes appear better able than wolves to live among people (Zimmerman 2005).

Hearing a coyote is much more common than seeing one. The calls a coyote makes are high-pitched and variously described as howls, yips, yelps, and barks. These calls may be a long rising and falling note (a howl) or a series of short notes (yips). These calls are most often heard at dusk or night, but may be heard in the day. Although these calls are made throughout the year, they are most common during the spring mating season and in the fall when the pups leave their families to establish new territories.

Coyotes have been known to live a maximum of 10 years in the wild and 18 years in captivity (Tokar 2001). They seem to be better than dogs at observational learning (Coppinger and Coppinger 2001).

Ecology

Diet and hunting

Coyotes are versatile carnivores with a 90 percent mammalian diet, depending on the season. They primarily eat small mammals, such as voles, eastern cottontails, ground squirrels, and mice, though they will eat birds, snakes, lizards, deer, javelina, and livestock as well as large insects and other large invertebrates. Though they will consume large amounts of carrion, they tend to prefer fresh meat. Part of the coyote's success as a species is its dietary adaptability. As such, coyotes have been known to eat human rubbish and domestic pets. Fruits and vegetables are a significant part of the coyote's diet in the autumn and winter months (Tokar 2001).

Coyotes shift their hunting techniques in accordance to their prey. When hunting small animals such as mice, they slowly stalk through the grass and use their acute sense of smell to track down the prey. When the prey is located, the coyotes stiffen and pounce on the prey in a cat-like manner. Coyotes will commonly work in teams when hunting large ungulates such as deer. Coyotes may take turns in baiting and pursuing the deer to exhaustion, or they may drive it towards a hidden member of the pack (Tokar 2001). When attacking large prey, coyotes attack from the rear and the flanks of their prey. Occasionally they also grab the neck and head, pulling the animal down to the ground. Coyotes are persistent hunters, with successful attacks sometimes lasting from 14 minutes to about 21 hours; even unsuccessful ones can vary from 2 minutes to more than 8 hours before the coyotes give up. Depth of snow can affect the likelihood of a successful kill (NPS 2006).

The average distance covered in a night's hunting is 4 kilometers (2½ mi) (Tokar 2001).

Interspecific predatory relationships

The gray wolf is a significant predator of coyotes wherever their ranges overlap. Since the Yellowstone Gray Wolf Reintroduction in 1995 and 1996, the local coyote population went through a dramatic restructuring. Until the wolves returned, Yellowstone National Park had one of the densest and most stable coyote populations in America due to a lack of human impacts. Two years after the wolf reintroductions, 50 percent of the pre-wolf population of coyotes had been reduced, through both competitive exclusion and predation. In Grand Teton, coyote densities were 33% lower than normal in the areas where they coexisted with wolves, and 39% lower in the areas of Yellowstone where wolves were reintroduced. In one study, about 16 percent of radio-collared coyotes were preyed upon by wolves (Robbins 1998; LiveScience 2007).

As a result of wolf reintroductions, Yellowstone coyotes have had to shift their territories, moving from open meadows to steep terrain. Carcasses in the open no longer attract coyotes; when a coyote is chased on flat terrain, it is often killed. They exhibit greater security on steep terrain, where they will often lead a pursuing wolf downhill. As the wolf comes after it, the coyote will turn around and run uphill. Wolves, being heavier, cannot stop as quickly and the coyote gets a huge lead. Though physical confrontations between the two species are usually dominated by the larger wolves, coyotes have been known to attack wolves if the coyotes outnumber them. Both species will kill each other's pups given the opportunity (Robbins 1998; LiveScience 2007).

Cougars sometimes kill coyotes. The coyote's instinctive fear of cougars has led to the development of anti-coyote sound systems that repel coyotes from public places by replicating the sounds of a cougar (QAW 2008).

In sympatric populations of coyotes and red foxes, fox territories tend to be located largely outside of coyote territories. The principal cause of this separation is believed to be active avoidance of coyotes by the foxes. Interactions between the two species vary in nature, ranging from active antagonism to indifference. The majority of aggressive encounters are initiated by coyotes, and there are few reports of red foxes acting aggressively toward coyotes except when attacked or when their pups were approached. Conversely, foxes and coyotes have sometimes been seen feeding together (Sargeant and Allen 1989).

Coyotes sometimes will form a symbiotic relationship with American badgers. Because coyotes are not very effective at digging rodents out of their burrows, they will chase the animals while they are above ground. Badgers on the other hand are not fast runners, but are well-adapted to digging. When hunting together, they effectively leave little escape for prey in the area (Tokar 2001).

In some areas, coyotes share their ranges with bobcats. It is rare for these two similarly sized species to physically confront one another, though bobcat populations tend to diminish in areas with high coyote densities. Coyotes (both single individuals and groups) have been known to occasionally kill bobcats, but in all known cases, the victims were relatively small specimens, such as adult females and juveniles (Gipson and Kamler 2002).

Coyotes have also competed with and occasionally eaten Canadian lynxes in areas where both species overlap (Unnell et al. 2006; CN 2008).

Reproduction

Female coyotes are monoestrus and remain in heat for 2 to 5 days between late January and late March, during which mating occurs. Once the female chooses a partner, the mated pair may remain temporarily monogamous for a number of years. Depending on geographic location, spermatogenesis in males takes around 54 days and occurs between January and February. The gestation period lasts from 60 to 63 days. Litter size ranges from 1 to 19 pups; though the average is 6 (Tokar 2001). These large litters act as compensatory measures against the high juvenile mortality rate, with approximately 50 to 70 percent of pups not surviving to adulthood (MDNR 2007).

The pups weigh approximately 250 grams at birth and are initially blind and limp-eared (Tokar 2001). Coyote growth rate is faster than that of wolves, being similar in length to that of the dhole (Cuon alpinus, Asiatic wild dog) (Fox 1984). The eyes open and ears erect after 10 days. Around 21 to 28 days after birth, the young begin to emerge from the den and by 35 days they are fully weaned. Both parents feed the weaned pups with regurgitated food. Male pups will disperse from their dens between months 6 and 9, while females usually remain with the parents and form the basis of the pack. The pups attain full growth between 9 and 12 months. Sexual maturity is reached by 12 months (Tokar 2001).

Interspecific hybridization

Coyotes will sometimes mate with domestic dogs, usually in areas like Texas and Oklahoma where the coyotes are plentiful and the breeding season is extended because of the warm weather. The resulting hybrids, called coydogs, maintain the coyote's predatory nature, along with the dog's lack of timidity toward humans, making them a more serious threat to livestock than pure blooded animals. This cross breeding has the added effect of confusing the breeding cycle. Coyotes usually breed only once a year, while coydogs will breed year-round, producing many more pups than a wild coyote. Differences in the ears and tail are generally what can be used to distinguish coydogs from domestic/feral dogs or pure coyotes.

Coyotes have also been known on occasion to mate with wolves, although this is less common as with dogs due to the wolf's hostility to the coyote. The offspring, known as a coywolf, is generally intermediate in size to both parents, being larger than a pure coyote, but smaller than a pure wolf. A study showed that of 100 coyotes collected in Maine, 22 had half or more wolf ancestry, and one was 89 percent wolf. A theory has been proposed that the large eastern coyotes in Canada are actually hybrids of the smaller western coyotes and wolves that met and mated decades ago as the coyotes moved toward New England from their earlier western ranges (Zimmerman 2005). The red wolf is thought by certain scientists to be in fact a wolf/coyote hybrid rather than a unique species. Strong evidence for hybridization was found through genetic testing, which showed that red wolves have only 5 percent of their alleles unique from either gray wolves or coyotes. Genetic distance calculations have indicated that red wolves are intermediate between coyotes and gray wolves, and that they bear great similarity to wolf/coyote hybrids in southern Quebec and Minnesota. Analyses of mitochondrial DNA showed that existing red wolf populations are predominantly coyote in origin (DOB 2008).

Relationship with humans

Adaptation to human environment

Despite being extensively hunted, the coyote is one of the few medium-to-large-sized animals that has enlarged its range since human encroachment began. It originally ranged primarily in the western half of North America, but it has adapted readily to the changes caused by human occupation and, since the early nineteenth century, has been steadily and dramatically extending its range (Gompper 2002). Sightings now commonly occur in California, Oregon, New England, New Jersey, and eastern Canada. Although missing in Hawaii, coyotes have been seen in nearly every continental U.S. state, including Alaska. Coyotes have moved into most of the areas of North America formerly occupied by wolves, and are often observed foraging in suburban trashcans.

Coyotes also thrive in suburban settings and even some urban ones. A study by wildlife ecologists at Ohio State University yielded some surprising findings in this regard. Researchers studied coyote populations in Chicago over a seven-year period (2000–2007), proposing that coyotes have adapted well to living in densely populated urban environments while avoiding contact with humans. They found, among other things, that urban coyotes tend to live longer than their rural counterparts, kill rodents, and small pets, and live anywhere from parks to industrial areas. The researchers estimate that there are up to 2,000 coyotes living in "the greater Chicago area" and that this circumstance may well apply to many other urban landscapes in North America (OSU 2006). In Washington DC's Rock Creek Park, coyotes den and raise their young, scavenge roadkill, and hunt rodents. As a testament to the coyote's habitat adaptability, a coyote (known as "Hal the Central Park Coyote") was even captured in Manhattan's Central Park, in March 2006, after being chased by city wildlife officials for two days.

Attacks on humans

Coyote attacks on humans are uncommon and rarely cause serious injuries, due to the relatively small size of the coyote. However, coyote attacks on humans have increased since 1998 in the state of California. Data from USDA Wildlife Services, the California Department of Fish & Game, and other sources show that while 41 attacks occurred during the period of 1988-1997, 48 attacks were verified from 1998 through 2003. The majority of these incidents occurred in Southern California near the suburban-wildland interface (Timm et al. 2004).

Due to an absence of harassment by residents, urban coyotes lose their natural fear of humans, which is further worsened by people intentionally feeding coyotes. In such situations, some coyotes begin to act aggressively toward humans, chasing joggers and bicyclists, confronting people walking their dogs, and stalking small children (Timm et al. 2004). Like wolves, non-rabid coyotes usually target small children, mostly under the age of 10, though some adults have been bitten. Some attacks are serious enough to warrant as many as 200 stitches (Linnell et al. 2002).

Fatal attacks on humans are very rare. In 1981 in Glendale, California, however, a coyote attacked a toddler who, despite being rescued by her father, died in surgery due to blood loss and a broken neck (Timm et al. 2004).

Livestock and pet predation

Coyotes are presently the most abundant livestock predators in western North America, causing the majority of sheep, goat, and cattle losses (Wade and Bowns 1997). According to the National Agricultural Statistics Service, coyotes were responsible for 60.5 percent of the 224,000 sheep deaths that were attributed to predation in 2004 (NASS), but the total number of sheep deaths in 2004 comprised only 2.22 percent of the total sheep and lamb population in the United States (NASS 2008). By virtue of the fact that coyote populations are typically many times greater and more widely distributed than those of wolves, coyotes cause more overall predation losses. However, an Idaho consensus taken in 2005 showed that individual coyotes were 20 times less likely to attack livestock than individual wolves (Collinge).

Coyotes will typically bite the throat just behind the jaw and below the ear when attacking adult sheep or goats, with death commonly resulting from suffocation. Blood loss is usually a secondary cause of death. Calves and heavily fleeced sheep are killed by attacking the flanks or hind-quarters, causing shock and blood loss. When attacking smaller prey, such as young lambs and kids, the kill is made by biting the skull and spinal regions, causing massive tissue and ossular damage. Small or young prey may be completely carried off, leaving only blood as evidence of a kill. Coyotes will usually leave the hide and most of the skeleton of larger animals relatively intact unless food is scarce, in which case they may leave only the largest bones. Scattered bits of wool, skin, and other parts are characteristic where coyotes feed extensively on larger carcasses (Wade and Bowns 1997).

Coyote predation can usually be distinguished from dog or coydog predation by the fact that coyotes partially consume their victims. Tracks are also an important factor in distinguishing coyote from dog predation. Coyote tracks tend to be more oval-shaped and compact than those of domestic dogs, plus, claw marks are less prominent and the tracks tend to follow a straight line more closely than those of dogs. With the exception of sighthounds, most dogs of similar weight to coyotes have a slightly shorter stride (Wade and Bowns 1997). Coyote kills can be distinguished from wolf kills by the fact that there is less damage to the underlying tissues. Also, coyote scats tend to be smaller than wolf scats (MSU 2006).

Coyotes are often attracted to dog food and animals that are small enough to appear as prey. Items like garbage, pet food, and sometimes even feeding stations for birds and squirrels will attract coyotes into backyards. Approximately 3 to 5 pets attacked by coyotes are brought into the Animal Urgent Care Hospital of South Orange County each week, the majority of which are dogs, since cats typically do not survive the attacks (Hardesty 2005). Scat analysis collected near Claremont, California, revealed that coyotes relied heavily on pets as a food source in winter and spring (Timm et al. 2004). At one location in Southern California, coyotes began relying on a colony of feral cats as a food source. Over time, the coyotes killed most of the cats and then continued to eat the cat food placed daily at the colony site by citizens who were maintaining the cat colony (Timm et al. 2004).

Coyotes attack smaller or similar sized dogs and they have been known to attack even large, powerful breeds like the Rottweiler in exceptional cases (NEN 2007). Dogs larger than coyotes are usually able to capably defend themselves, although small breeds are more likely to suffer injury or be killed by such attacks.

Pelts

In the early days of European settlement in North Dakota, American beavers were the most valued and sought after furbearers, though other species were also taken, including coyotes (NPWRC 2006a). Coyotes are an important furbearer in the region. During the 1983-86 seasons, North Dakota buyers purchased an average of 7,913 pelts annually, for an average annual combined return to takers of $255,458. In 1986-87, South Dakota buyers purchased 8,149 pelts for a total of $349,674 to takers (NPWRC 2006b).

The harvest of coyote pelts in Texas has varied over the past few decades, but has generally followed a downward trend. A study from the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, however, found that there was no indication of population decline, and suggested that, as pelt prices were not increasing, the decrease in harvest was likely due to decreasing demand, and not increasing scarcity (where pelt prices would go up). It suggested that fashion, and the changing custom of wearing fur garments, may be significant among these factors (Cpple 1995).

Today, coyote fur is still used for full coats and trim and is particularly popular for men’s coats.

Coyotes and culture

Traditional stories from many Native American nations include a character whose name is translated into English as "Coyote." Although especially common in stories told by southwestern Native American nations, such as the Diné and Apache, stories about Coyote appear in dozens of Native American nations from Canada to Mexico.

Usually appearing as a trickster, a culture hero or both, Coyote also often appears in creation myths and etiological myths. Although usually appearing in stories as male, Coyote can also be female or even a hermaphrodite, in some traditional Native American stories.

The coyote is a popular figure in folklore and popular culture. References may invoke either the animal or the mythological figure. Traits commonly described in pop culture appearances include inventiveness, mischievousness, and evasiveness.

Genus controversy

In 1816, in the third volume of Lorenz Oken's Lehrbuch der Naturgeschichte, the author found sufficient similarities in the dentition of coyotes and jackals to place these species into a new separate genus from Canis called Thos after the classical Greek word θώς (jackal). Oken's idiosyncratic nomenclatorial ways, however, aroused the scorn of a number of zoological systematists. Nearly all the descriptive words used to justify the genus division were relative terms without a reference measure, and the argument did not take into account the size differences between the species, which can be considerable. Angel Cabrera, in his 1932 monograph on the mammals of Morocco, briefly touched upon the question of whether or not the presence of a cingulum on the upper molars of the jackals and its corresponding absence in the rest of Canis could justify a subdivision of the genus Canis. In practice, he chose the undivided-genus alternative and referred to the jackals as Canis (Homann 2004). A few authors, however, Ernest Thompson Seton being among them, accepted Oken's nomenclature, and went as far as referring to the coyote as American jackal (Seton 2006).

The Oken/Heller proposal of the new genus Thos did not affect the classification of the coyote. Gerrit S. Miller still had, in his 1924 edition of List of North American Recent Mammals, in the section “Genus Canis Linnaeas,” the subordinate heading “Subgenus Thos Oken” and backed it up with a reference to Heller. In the reworked version of the book in 1955, Philip Hershkovitz and Hartley Jackson led him to drop Thos both as an available scientific term and as a viable subgenus of Canis. In his definitive study of the taxonomy of the coyote, Jackson had, in response to Miller, queried whether Heller had seriously looked at specimens of coyotes prior to his 1914 article and thought the characters to be "not sufficiently important or stable to warrant subgeneric recognition for the group" (Homann 2004).

Subspecies

There are 19 recognized subspecies of this canid (Wozencraft 2005):

- Mexican coyote, Canis latrans cagottis

- San Pedro Martir coyote, Canis latrans clepticus

- Salvador coyote, Canis latrans dickeyi

- South-eastern coyote, Canis latrans frustor

- Belize coyote, Canis latrans goldmani

- Honduras coyote, Canis latrans hondurensis

- Durango coyote, Canis latrans impavidus

- Northern coyote, Canis latrans incolatus

- Tiburon Island coyote, Canis latrans jamesi

- Plains coyote, Canis latrans latrans

- Mountain coyote, Canis latrans lestes

- Mearns coyote, Canis latrans mearnsi

- Lower Rio Grande coyote, Canis latrans microdon

- California Valley coyote, Canis latrans ochropus

- Peninsula coyote, Canis latrans peninsulae

- Texas Plains coyote,Canis latrans texensis

- North-eastern coyote, Canis latrans thamnos

- Northwest Coast coyote, Canis latrans umpquensis

- Colima coyote, Canis latrans vigilis

Notes

- ↑ W. C. Wozencraft, "Order Carnivora," in D. E. Wilson and D. M. Reeder (eds.), Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. (Washington : Smithsonian Institution Press, 1993). ISBN 1560982179.

- ↑ C. Sillero-Zubiri, and M. Hoffmann, Canid Specialist Group, "Canis latrans," 2007 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (2004 assessment). Retrieved October 2, 2008. Database entry includes justification for why this species is of least concern.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) and J. G. Doherty (Wildlife Conservation Society). Speed of animals. Infoplease.com. Sourced from Natural History Magazine March 1974. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- Bekoff, M. Canis Latrans, Species Account. American Society of Mammalogists No. 79., 1977.

- Conservation Northwest (CN). Canada lynx: Wild cat of the Loomis—and more. Conservation Northwest. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- Coppinger, R., and L. Coppinger. Dogs: A Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior and Evolution. New York: Scribner, 2001. ISBN 0684855305

- Fox, M. W. The Whistling Hunters: Field Studies of the Asiatic Wild Dog (Cuon Alpinus). Albany: State University of New York Press, 1984. ISBN 0873958438

- Gipson, P. S., and J. F. Kamler. "Bobcat killed by a coyote." The Southwestern Naturalist 47(3) (2002): 511-513.

- Gompper, M. Top carnivores in the suburbs? Ecological and conservation issues raised by colonization of North-eastern North America by coyotes. BioScience 52 (2002):185-190.

- LiveScience Staff. Coyotes cower in wolf territory. Livescience, 2007. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- Macdonald, D. The Encyclopedia of Mammals. London: Allen & Unwin, 1984. ISBN 004500028x

- McClennen, N., R. Wigglesworth, and S. H. Anderson. "The effect of suburban and agricultural development on the activity patterns of coyotes (Canis latrans)." American Midland Naturalist 146 (2001): 27-36.

- Mech, D. L., and L. Boitani. Wolves: Behavior, Ecology and Conservation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003. ISBN 0226516962

- Moehlman, P., and H. Hofer. Cooperative breeding, reproductive suppression, and body mass in canids. In N. G. Solomon and J. A. French, Cooperative Breeding in Mammals. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997. ISBN 0521454913

- Morey, P. Landscape use and diet of coyotes, Canis latrans, in the Chicago metropolitan area. Masters Thesis, Utah State University, 2004.

- Nash, Gary B. Encyclopedia of American History. New York: Facts on File, 2003. ISBN 081604371X

- Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center (NPWRC). Prairie Basin Wetlands of the Dakotas: A community profile. Chapter 3. Biotic environment. Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, United States Geological Survey, 2006. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- Parker, G. Eastern Coyote: Story of Its Success. Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada: Nimbus Publishing, 1995. ISBN 1551091119

- Sargeant, A. B., and S. H. Allen. Observed interactions between coyotes and red foxes. Journal of Mammalogy 70(3) (1989):631-633. On Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center Online. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- Schwartz, C. W., and E. R. Schwartz. The Wild Mammals of Missouri, 2nd revised edition. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2001. ISBN 0826213596

- Seton, E. T. Art Anatomy of Animals. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2006. ISBN 0486447472.

- Timm, R. M., R. O. Baker, J. R. Bennett, and C. C. Coolahan. 2004. Coyote attacks: An increasing suburban problem. Hopland Research & Extension Center. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- Tokar, E. Canis latrans. Animal Diversity Web, 2001. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- Unnell, K. D., J. T. Flinders, and M. L. Wolfe. Potential impacts of coyotes and snowmobiles on lynx conservation in the intermountain West. Wildlife Society Bulletin 34(3) (2006): 828–838.

- Voigt, D. R., and W. E. Berg. "Coyote." In M. Novak, Wild Furbearer Management and Conservation in North America. Section IV: Species Biology, Management, and Conservation, Chapter 28. Ontario, Canada: Queen's Printer, 1999. Produced by the Ontario Fur Managers Federation under license from the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. ISBN 0774393653

- Wozencraft, W. C. Coyote. In D. E. Wilson and D. M. Reeder (eds.). Mammal Species of the World, 3rd edition]. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005. ISBN 0801882214

- Zimmerman, D. Eastern coyotes are becoming coywolves. Caledonian Record July 2, 2005. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.