Panama

| República de Panamá Republic of Panama |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: "Pro Mundi Beneficio" (Latin) "For the Benefit of the World" |

||||||

| Anthem: Himno Nacional de Panamá (Spanish) National anthem of Panama |

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) | Panama 8°58′N 79°32′W | |||||

| Official languages | Spanish | |||||

| Demonym | Panamanian | |||||

| Government | Constitutional Democracy | |||||

| - | President | Juan Carlos Varela | ||||

| - | Vice President | Isabel Saint Malo | ||||

| Independence | ||||||

| - | from Spain | 28 November 1821 | ||||

| - | from Colombia | 3 November 1903 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 75,517 km² (118th) 29,157 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 2.9 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2018 estimate | 3,800,644[1] | ||||

| - | 2010 census | 3,661,868[2] | ||||

| - | Density | 54/km² (162) 145/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $107.037 billion[3] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $25,737[3] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2018 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $63.683 billion[3] (78) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $15,313[3] (52) | ||||

| Gini (2015) | 51.0[4] | |||||

| Currency | Balboa, U.S. dollar (PAB, USD) |

|||||

| Time zone | (UTC-5) | |||||

| Internet TLD | .pa | |||||

| Calling code | [[++507]] | |||||

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama (Spanish: República de Panamá), is the southernmost country of Central America. Situated on an isthmus, Panama is a transcontinental nation which connects North and South America. It borders Costa Rica to the west, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the north and the Pacific Ocean to the south. Panama was the home to the first Spanish colony on the Pacific Ocean and served as a crucial staging point between various nations since that time. Best known today as the home of the Panama Canal, it remains one of the most strategic transportation hubs in the world. International affairs and world commerce are highly dependent upon the Canal.

The culture, customs, and language of Panamanians are predominantly Caribbean and Spanish. Ethnically, the majority of the population is mestizo of mixed Amerindian and European descent. Its vibrant music and culture draw tourists from around the world. However, political and social turmoil plagued the nation throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, inhibiting its growth and advancement.

Spanish is the official and dominant language; English is spoken widely on the Caribbean coast and by many in business and professional fields. More than half the population lives in the Panama City–Colón metropolitan corridor. Panama is an international business center and also a transit country. Although it is the third largest economy in Central America, after Guatemala and Costa Rica, it is the largest consumer in Central America.

Geography

Panama is a country located in Central America, bordering both the Caribbean Sea and the North Pacific Ocean, between Colombia and Costa Rica. Panama is located on the narrowest and lowest part of the Isthmus of Panama that links North America and South America. This S-shaped part of the isthmus is situated between 7° and 10° north latitude and 77° and 83° west longitude. Panama encompasses approximately 78,200 square kilometers, is 772 kilometers in length, and between 60 and 177 kilometers in width.

Coastal areas

Panama's two coastlines are referred to as the Caribbean (or Atlantic) and Pacific, rather than the north and south coasts. Because of the location and contour of the country, directions expressed in terms of the compass are often misleading. For example, a transit of the Panama Canal from the Pacific to the Caribbean involves travel not to the east but to the northwest, and in Panama City the sunrise in the east is over the Pacific. From Cerro Jefe, near Panama City, it is possible to see both the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean from the same location.

The Caribbean coastline is marked by several good natural harbors. However, Cristóbal, at the Caribbean terminus of the canal, had the only important port facilities in the late 1980s. The numerous islands of the Archipiélago de Bocas del Toro, near the Beaches of Costa Rica, provide an extensive natural roadstead and shield the banana port of Almirante. The over 350 San Blas Islands, near Colombia, which are strung for more than 160 kilometers along the sheltered Caribbean coastline, also belong to Panama.

The major port on the Pacific coastline is Balboa. The principal islands are those of the Archipiélago de las Perlas in the middle of the Gulf of Panama, the penal colony on the Isla de Coiba in the Golfo de Chiriquí, and the decorative island of Taboga, a tourist attraction that can be seen from Panama City. In all, there are some 1,000 islands off the Pacific coast.

The Pacific coastal waters are extraordinarily shallow. Depths of 180 meters are reached only outside the perimeters of both the Gulf of Panama and the Golfo de Chiriquí, and wide mud flats extend up to 70 kilometers seaward from the coastlines. As a consequence, the tidal range is extreme. A variation of about 70 centimeters between high and low water on the Caribbean coast contrasts sharply with over 700 centimeters on the Pacific coast, and some 130 kilometers up the Río Tuira the range is still over 500 centimeters.

The country's two international borders, with Colombia and Costa Rica, have been clearly demarcated, and in the late 1980s there were no outstanding disputes. The country claims the seabed of the continental shelf, which has been defined by Panama to extend to the 500-meter submarine contour. In addition, a 1958 law asserts jurisdiction over 12 nautical miles from the coastlines, and in 1968 the government announced a claim to a 200 nautical mile Exclusive Economic Zone.

Landforms

The dominant feature of the country's landform is the central spine of mountains and hills that forms the continental divide. The divide does not form part of the great mountain chains of North America, and only near the Colombian border are there highlands related to the Andean system of South America. The spine that forms the divide is the highly eroded arch of an uplift from the sea bottom, in which peaks were formed by volcanic intrusions.

The mountain range of the divide is called the Cordillera de Talamanca near the Costa Rican border. Farther east it becomes the Serranía de Tabasará, and the portion of it closer to the lower saddle of the isthmus, where the canal is located, is often called the Sierra de Veraguas. As a whole, the range between Costa Rica and the Canal is generally referred to by Panamanian geographers as the Cordillera Central.

The highest point in the country is the Volcán Barú (formerly known as the Volcán de Chiriquí), which rises to 11,401 ft. (3475 meters). The apex of a highland that includes the nation's richest soil, the Volcán Barú is still referred to as a volcano, although it has been inactive for millennia. Panama is also home to Balboa Hill, which offers a view of both the Pacific Ocean and the Atlantic Ocean.

Nearly 500 rivers lace Panama's rugged landscape. Mostly unnavigable, many originate as swift highland streams, meander in valleys, and form coastal deltas. The Kampia Lake and Madden Lake (filled with water from the Río Chagres) provide hydroelectricity for the area of the former Canal Zone. The Río Chepo, a major source of hydroelectric power, is one of the more than 300 rivers emptying into the Pacific. These Pacific-oriented rivers are longer and slower running than those of the Caribbean side. Their basins are also more extensive. One of the longest is the Río Tuira which flows into the Golfo de San Miguel and is the nation's only river navigable by larger vessels.

Climate

Panama has a tropical climate. Temperatures are uniformly high—as is the relative humidity—and there is little seasonal variation. Diurnal ranges are low; on a typical dry-season day in the capital city, the early morning minimum may be 24°C and the afternoon maximum 29°C. The temperature seldom exceeds 32°C for more than a short time. The humidity however, is around 80 percent for most of the year. Temperatures on the Pacific side of the isthmus are somewhat lower than on the Caribbean, and breezes tend to rise after dusk in most parts of the country. Temperatures are markedly cooler in the higher parts of the mountain ranges, and frosts occur in the Cordillera de Talamanca in western Panama.

Climatic regions are determined less on the basis of temperature than on rainfall, which varies regionally from less than 1.3 to more than 3 meters per year. Almost all of the rain falls during the rainy season, which is usually from April to December, but varies in length from seven to nine months. The cycle of rainfall is determined primarily by two factors: Moisture from the Caribbean, which is transported by north and northeast winds prevailing during most of the year, and the continental divide, which acts as a rainshield for the Pacific lowlands. A third influence that is present during the late autumn is the southwest wind off the Pacific. This wind brings some precipitation to the Pacific lowlands, modified by the highlands of the Península de Azuero, which form a partial rainshield for much of central Panama. In general, rainfall is much heavier on the Caribbean than on the Pacific side of the continental divide. The annual average in Panama City is little more than half of that in Colón. Although rainy season thunderstorms are common, the country is for the most part outside the normal path for Atlantic hurricanes.

Plant life

Panama's tropical environment supports an abundance of plants. Forests dominate, interrupted in places by grasslands, scrub, and crops. Although nearly 40 percent of Panama is still wooded, deforestation is a continuing threat to the rain-drenched woodlands. Tree cover has been reduced by more than 50 percent since the 1940s. A nearly impenetrable jungle forms the Darien Gap between Panama and Colombia. It creates a break in the Pan-American Highway, which otherwise forms a complete road from Alaska to Patagonia. Subsistence farming, widely practiced from the northeastern jungles to the southwestern grasslands, consists largely of corn, bean, and tuber plots. Mangrove swamps occur along parts of both coasts, with banana plantations occupying deltas near Costa Rica. In many places, a multi-canopied rain forest abuts the swamp on one side of the country and extends to the lower reaches of slopes in the other.

Provinces

The country is divided into nine provinces, as well as several indigenous comarcas (administrative region for an area with a substantial Indian population). The provincial borders have not changed since they were determined at independence in 1903. The provinces are divided into districts, which in turn are subdivided into sections called "corregimientos." Configurations of the corregimientos are changed periodically to accommodate population changes as revealed in the census reports.

History

Panama had a rich Pre-Colombian heritage of native populations whose presence stretched back over 12,000 years. The earliest traces of these indigenous peoples include fluted projectile points. Central Panama was home to some of the first pottery-making villages in the Americas, such as the Monagrillo culture dating to about 2500-1700 B.C.E. These evolved into significant populations that are best known through the spectacular burials of the Conte site (dating to circa 500-900 C.E.) and the beautiful polychrome pottery of the Coclé style. At the time of European conquest, the indigenous population of the isthmus was said to be between one and two million people. Prior to the arrival of Europeans, Panama was widely settled by Chibchan, Chocoan, and Cueva peoples, among whom the largest group were the Cueva (whose specific language affiliation is poorly documented).

Spanish conquest

In 1501, Rodrigo de Bastidas from Seville, who had accompanied Columbus on his second voyage to the Americas, sailed westward from the Atlantic side of present day Venezuela in an attempt to militarily observe the coastline of the Caribbean basin. Though the poor condition of his ships forced him to turn back and return to Santo Domingo to effect repairs, de Bastidas would reach La Punta de Manzanillo on Panama's northern Caribbean coast before having to abandon his effort. He is acknowledged to be the first European to have claimed that part of the isthmus, which includes the San Blas region of the Kuna Indians.

A year after de Bastidas's arrival in Panama and on his fourth trip to the Americas, Columbus sailed south to the isthmus from the northern, present day Central American states of Honduras and Costa Rica. Columbus produced hand drawn maps of Panama's coastline and unlike de Bastidas, explored Panama's western territories. He landed in what is present day Almirante, in the Bocas del Toro province, and proceeded along the coast to a part of the territory he would name Veragua meaning "to see water." He continued his coastal journey up to the Chagres River, taking refuge in a natural bay he christened Portobelo (Beautiful Port). This site would become a key port for colonial Spain in 1597, replacing Nombre de Dios which had burned and proven to be vulnerable to attack. Columbus ended his explorations at Del Retrete having spent just shy of two months in what would be Panama.

Soon Spanish explorations would converge upon Tierra Firma (also Tierra Firme, Spanish from the Latin terra firma, "dry land" or "mainland") which served in Spanish colonial times as the name for the Isthmus of Panama. Panama was explored and settled by the Spanish in the sixteenth century. In 1821, under the leadership of the then-colonel in command, José de Fábrega, it broke with the Spanish Crown and joined Simón Bolívar's Republic of Gran Colombia. When this dissolved in 1830, Panama remained part of Colombia.

Panama was part of the Spanish Empire for over 300 years (1513-1821) and Panamanian fortunes fluctuated with the geopolitical importance of the isthmus to the Spanish crown. Panama's importance would wane to insignificance by the middle of the eighteenth century as Spanish influence and power in Europe decreased and Spanish ships began to increasingly circle Cape Horn in order to reach the Atlantic. While the Panama route was short it was also labor intensive and expensive because of the loading and unloading and laden-down trek required to get from the one coast to the other. The Panama route was also vulnerable to attack from pirates (mostly Dutch and English) and from "new world" Africans called cimarrons who had freed themselves from enslavement and lived in communes or palenques around the Camino Real in Panama's interior, and on some of the islands off Panama's Pacific coast.

When Panama was colonized, the indigenous peoples who survived the many diseases, massacres and enslavement of the conquest ultimately fled into the forest or to nearby islands. Indian slaves were replaced by Africans.

Independence

Panama joined the independence bandwagon as did most of the other Central American countries, in 1821. While Panama was of great historical importance to the Spanish Empire, the differences in social and economic status between the more liberal area of Azuero, and the much more royalist and conservative area of Veraguas displayed contrasting perspectives. It is, in fact, known that when the Grito de la Villa de Los Santos occurred, Veraguas firmly opposed the motion for independence.

In 1821 the isthmus joined the recently formed Republic of Colombia which consisted of Venezuela, New Granada (present day Colombia) and finally Ecuador, which joined in 1822. The Republic of Colombia (1819-1830) or ‘Gran Colombia’ as it began to be called only after 1886, more or less corresponded in territory to the old colonial administrative district called the Viceroyalty of New Granada (1717-1819). While Panama had also been included in that scheme during the colonial period, for all practical purposes her economic and political ties had been much closer to the Viceroyalty of Peru (1542-1821). Nevertheless, Panama voluntarily joined Bolivar's project and became Department of the Isthmus, under a number of successive governors.

In September 1830, under the guidance of General José Domingo Espinar, the local military commander who rebelled against the nation's central government in response to his being transferred to another command, Panama separated from the Republic of Colombia and requested that general Simón Bolívar take direct command of the isthmus department. This was a condition to its reunification with the rest of the country. Bolívar rejected Espinar's actions, and though he did not assume control of the isthmus he desired, he called for Panama to rejoin the central state. Because of the overall political tension, Republic of Colombia's final days were approaching. Bolívar's vision for territorial unity disintegrated finally when General Juan Eligio Alzuru undertook a military coup against Espinar's authority. By early 1831, with order restored, Panama reincorporated itself to what was left of the republic—a territory now slightly larger than present day Panama and Colombia combined—which by then had adopted the name of Republic of New Granada. The alliance of the two nations would last seventy years and prove precarious.

By July 1831, as the new countries of Venezuela and Ecuador were being established, the isthmus would again declare its independence, now under the same General Alzuru as supreme military commander. Abuses committed by Alzuru's shortlived administration were countered by military forces under the command of Colonel Tomás Herrera, resulting in the defeat and execution of Alzuru in August, and the reestablishment of ties with New Granada.

In November 1840, during a civil war that had begun as a religious conflict, the isthmus under the leadership of, now General, Tomás Herrera, who assumed the title of Superior Civil Chief, declared its independence as did multiple other local authorities. In March 1841, the State of Panama adopted the name 'Estado Libre del Istmo', or the Free State of the Isthmus. The new state established external political and economic ties and by March 1841, had drawn up a constitution which included the possibility for Panama to rejoin New Granada, but only as a federal district. Herrera's title was first changed to Superior Chief of State in March 1841 and in June 1841, to President. By the time the civil conflict ended and the government of New Granada along with the government of the Isthmus had negotiated the Isthmus' reincorporation to the union, Panama's First Republic had been free for 13 months. Reunification occurred on December 31, 1841.

U.S. intervention

In the 1840s, two decades after the Monroe Doctrine declared the Western Hemisphere to be in the United States sphere of influence, North American and French interests became excited about the prospects of constructing railroads and/or canals through Central America to quicken trans-oceanic travel. At the same time, it was clear that New Granada’s control over the isthmus was turning increasingly untenable. In 1846, the United States and New Granada signed the Bidlack Mallarino Treaty, granting the U.S. rights to build railroads through Panama, and—most significantly—the power to militarily intervene against revolt to guarantee New Granadine control of the isthmus. The world's first transcontinental railroad, the Panama Railway, was completed in 1855 across the Isthmus from Aspinwall/Colón to Panama City.[5]

From 1850 until 1903, the United States used troops to suppress separatist uprisings and quell social disturbances on many occasions, creating a long-term animosity among the Panamanian people against the US military and resentment against Bogotá. The Bidlack-Mallarino Treaty would usher in a new era of U.S. intervention which would linger on into the new millennium. The first of many such conflicts was known as the Watermelon War of 1856, where U.S. soldiers mistreated locals, causing large-scale race riots that U.S. Marines eventually put down.

On November 3, 1903, Panama declared its independence from Colombia. The U.S. Battleship Nashville prevented the Colombian military from sailing to Panama. An invasion through the dense Panamanian jungle was impossible. The President of the Municipal Council, Demetrio H. Brid, highest authority at the time, became its de facto President, appointing a Provisional Government on November 4, to run the affairs of the new republic. The United States, as the first country to recognize the new Republic of Panama, sent troops to protect its economic interests. The 1904 Constituent Assembly elected Dr. Manuel Amador Guerrero, a prominent member of the Conservative political party, as the first constitutional President of the Republic of Panama.

From 1903 until 1968, Panama was a republic dominated by a commercially-oriented oligarchy. During the 1950s, the Panamanian military began to challenge the oligarchy's political hegemony. The January 9, 1964 Martyrs' Day riots escalated tensions between the country and the U.S. government over its long-term occupation of the Canal Zone. Twenty rioters were killed, and 500 other Panamanians were wounded.

In October 1968, Dr. Arnulfo Arias Madrid, elected president for the third time and twice ousted by the Panamanian military, was again ousted (for the third time) as president by the corrupt National Guard after only 10 days in office. A military junta government was established, and the commander of the National Guard, Brig. Gen. Omar Torrijos, emerged as the principal power in Panamanian political life. Torrijos' regime was harsh and corrupt, and had to confront the mistrust of the people and guerrillas backing the populist Arnulfo Arias. However, he was a charismatic leader whose populist domestic programs and nationalist foreign policy appealed to the rural and urban constituencies largely ignored by the oligarchy.

The Panama Canal

Enthused by the success of the Suez Canal, the French, under Ferdinand de Lesseps, began construction on the Panama Canal, a sea-level canal, on January 1, 1880. In 1893, after a great deal of work, the French scheme was abandoned due to disease and the sheer difficulty of building a sea-level canal, as well as lack of French field experience.[6] Although no detailed records were kept, as many as 22,000 workers are estimated to have died during the main period of French construction, which was a leading factor in the project's abandonment, besides the financial scandal that broke out in Paris from fraudulent funding of the canal project by unscrupulous financiers.

In 1904, the United States began work on the project after having bought the French equipment and excavations. President Theodore Roosevelt negotiated control of the Panama Canal Zone after having helped Panama to declare independence from Colombia.

A significant investment was made in eliminating disease from the area, particularly yellow fever and malaria, the causes of which had recently been discovered. With the diseases under control, and after significant work on preparing the infrastructure, construction of an elevated canal with locks began in earnest. The canal was formally opened on August 15, 1914, with the transit of the cargo ship Ancon.[7]

After World War II, United States control of the canal and the Canal Zone surrounding it became contentious as relations between Panama and the U.S. became increasingly tense. Many Panamanians felt that the Canal Zone rightfully belonged to Panama; student protests were met by the fencing in of the zone and an increased military presence. Negotiations toward a new settlement began in 1974, and resulted in the Torrijos-Carter Treaties. Signed by President Jimmy Carter and Omar Torrijos of Panama on September 7, 1977, this set in motion the process of handing the canal over to Panamanian control without charge. Though controversial within the U.S., the treaty led to gradual Panamanian control, with full control to become effective on December 31, 1999, at which time it was transferred to the Panama Canal Authority (ACP).

Manuel Noriega and the American invasion

President Torrijos died in a mysterious plane crash on August 1, 1981. The circumstances of his death generated charges and speculation that he was the victim of an assassination plot. Torrijos' death altered the tone but not the direction of Panama's political evolution. Despite 1983 constitutional amendments, which appeared to proscribe a political role for the military, the Panama Defense Forces (PDF), as they were then known, continued to dominate Panamanian political life behind a facade of civilian government. By this time, Gen. Manuel Noriega was firmly in control of both the PDF and the civilian government, and had created the Dignity Battalions to help suppress opposition.

Despite covert collaboration with Ronald Reagan on his Contra war in Nicaragua, relations between the United States and the Panama regime worsened in the 1980s. The United States froze economic and military assistance to Panama in the summer of 1987, in response to the domestic political crisis and an attack on the U.S. embassy. General Noriega's February 1988 indictment in U.S. courts on drug trafficking charges sharpened tensions. In April 1988, President Reagan invoked the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, freezing Panamanian Government assets in U.S. banks, withholding fees for using the canal, and prohibiting payments by American agencies, firms, and individuals to the Noriega regime. The country went into turmoil.

When national elections were held in May 1989, the elections were marred by accusations of fraud from both sides. However, the elections proceeded as planned, and Panamanians voted for the anti-Noriega candidates by a margin of over three-to-one. When Guillermo Endara won the election, the Noriega regime annulled the election, citing massive U.S. interference. Foreign election observers, including the Catholic Church and former U.S. President Jimmy Carter, certified the electoral victory of Endara despite widespread attempts at fraud by the regime. At the behest of the United States, the Organization of American States convened a meeting of foreign ministers but was unable to obtain Noriega's departure. By the fall of 1989, the regime was barely clinging to power.

The U.S. began sending thousands of troops to bases in the Canal Zone. Panamanian authorities alleged that U.S. troops left their bases and illegally stopped and searched vehicles in Panama. During this time, an American Marine got lost in the former French quarter of Panama City, ran a roadblock, and was killed by Panamanian Police (who were then a part of the Panamanian Military). On December 20, 1989, the United States troops commenced an invasion of Panama. Their primary objectives were achieved quickly, and the combatants' withdrawal began on December 27. Endara was sworn in as President at a U.S. military base on the day of the invasion.

General Manuel Noriega is now serving a 40-year sentence for drug trafficking. Estimates as to the loss of life on the Panamanian side vary between 500 and 7,000. Much of the Chorillo neighborhood was destroyed by fire shortly after the start of the invasion. Following the invasion, President George H. W. Bush announced one billion dollars in aid to Panama. Of this amount, $400 million consisted of incentives for U.S. business to export products to Panama, $150 million was to pay off bank loans and $65 million went to private sector loans and guarantees to U.S. investors.[8] The entire Panama Canal, the area supporting the Canal, and remaining U.S. military bases were turned over to Panama on December 31, 1999, in accordance with the treaty signed two decades prior.

Politics

The politics of Panama takes place in a framework of a presidential representative democratic republic, whereby the President of Panama is both head of state and head of government, and of a pluriform multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and the National Assembly. The Judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature. The branches are according to Panama's Political Constitution of 1972, reformed by the Actos Reformatorios of 1978, and by the Acto Constitucional in 1983, united in cooperation and limited through the classic system of checks and balances. Three independent organizations with clearly defined responsibilities are found in the Political Constitution. Thus, the Comptroller General of the Republic has the responsibility to manage public funds. There also exists the Electoral Tribunal, which has the responsibility to guarantee liberty, transparency, and the efficacy of the popular vote; and, finally, the Ministry of the Public exists to oversee interests of State and of the municipalities.

Administrative divisions

Administratively, Panama's major divisions are nine provinces and five indigenous territories (comarcas indígenas).

- Provinces

- Bocas del Toro · Coclé · Colón · Chiriquí · Darién · Herrera · Los Santos · Panamá · Veraguas

- Provincial-level comarcas

- Emberá-Wounaan · Kuna Yala · Ngöbe-Buglé · Kuna de Madugandí · Kuna de Wargandí

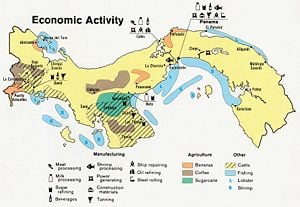

Economy

Panama's economy is service-based, heavily weighted toward banking, commerce, and tourism, due to its key geographic location. The handover of the canal and military installations by the U.S. has given rise to new construction projects. The Martín Torrijos (son of Omar Torrijos) administration has undertaken controversial structural reforms, such as a fiscal reform and a very difficult Social Security Reform. Furthermore, a referendum regarding the building of a third set of locks for the Panama Canal was approved overwhelmingly (though with low voter turnout) on October 22, 2006.

The Panamanian currency is the balboa, fixed at parity with the United States dollar. In practice, however, the country is dollarized; Panama mints its own coinage but uses U.S. dollars for all its paper currency. Panama is one of three countries in the region to have dollarized their economies, the other two being Ecuador and El Salvador.

The high levels of Panamanian trade are in large part due to the Colón Free Trade Zone, the largest free trade zone in the Western Hemisphere. Last year the zone accounted for 92 percent of Panama's exports and 65 percent of its imports, according to an analysis of figures from the Colon zone management and estimates of Panama's trade by the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

Panama fares decently in tourism receipts and foreign direct investment as a percent of GDP (the fourth-highest in Latin America in both categories) and Internet penetration (eighth-highest rate in Latin America).

Income inequality is a problem in this country. According to the Inter-American Development Bank, Panama has one of the worst levels of income inequality in the continent, even though it is one of the wealthiest countries in Central America.

Demographics

Because of its historical reliance on commerce, Panama is above all a melting pot. This is shown, for instance, by its considerable population of people of Chinese origin. Many Chinese immigrated to Panama to help build the Panama Railroad in the nineteenth century, although larger numbers have immigrated over the last few decades mostly as economic immigrants. At least 6 percent of Panama's population are of full or partial Chinese descent. A term for "corner store" in Panamanian Spanish is el chinito (the little chinese man), reflecting the fact that many corner stores are owned and run by Chinese immigrants.

Many languages, including seven indigenous ones, are spoken in Panama, although Spanish is the official and dominant language. English is now a second official language, is spoken natively by the West Indian (mainly of African origin) population, and is a second language for many professionals.

More than half the population lives in the Panama City-Colón metropolitan corridor. Panama City was enriched by the past century of American influences in terms of additions to the country's Latin culture, economics (the U.S. was involved in development of roads, schools and medical care), and international trade by the nearby Panama Canal, once under U.S. jurisdiction.

Panama is rich in folklore and popular traditions. Brightly colored national dress is worn during local festivals and the pre-Lenten carnival season, especially for traditional folk dances like the tamborito. Lively salsa—a mixture of Latin American popular music, rhythm and blues, jazz, and rock—is a Panamanian specialty, and Rubén Blades its best-known performer. Indian influences dominate handicrafts such as the famous Kuna textile molas. Artist Roberto Lewis' Presidential Palace murals and his restoration work and ceiling in the National Theater are well known and admired.

There are seven indigenous peoples in Panama:

- Emberá

- Wounaan

- Guaymí

- Buglé

- Kuna

- Naso

- Bribri

Nearly 90 percent of Panamanians are literate. Panamanian students attend the University of Panama, the Technological University, and the University of Santa Maria La Antigua, a private Catholic institution. Including smaller colleges, there are 14 institutions of higher education in Panama.

Culture

The culture of Panama was strongly influenced by European music, art and traditions that were brought to the country by settlers from Spain. These Spanish cultural influences blended with those from African and the indigenous peoples. For example, the tamborito is a Spanish dance that was blended with Native American rhythms, themes and dance moves. Dance is a symbol of the diverse cultures that have coupled in Panama.

The local folklore can be experienced through a multitude of festivals, dances and traditions that have been handed down from generation to generation. Local cities host live Reggae en Español, Cuban, Reggaeton (popular with the younger generation), Kompa, Colombian, jazz, blues, salsa, reggae and rock performances. Outside of Panama City, regional festivals take place throughout the year featuring local musicians and dancers.

Another example of Panama’s blended culture is reflected in the traditional products, such as woodcarvings, ceremonial masks and pottery, as well as in its architecture, cuisine and festivals. In earlier times, baskets were woven for utilitarian uses, but now many villages rely economically almost exclusively on the baskets they produce for tourists.

An example of unique culture in Panama stems from the Kuna Indians who are known for molas. Mola is the Kuna Indian word for blouse, but the term mola has come to mean the elaborate embroidered panels that make up the front and back of a Kuna woman's blouse. Molas are works of art created by the women of the tribe. They are several layers of cloth varying in color that are loosely stitched together using an appliqué process referred to as "reverse appliqué."

The best overview of Panamanian culture is found in the 'Museum of the Panamanian in Panama City. Other views can be found at the Museum of Panamanian History, the Museum of Natural Sciences, the Museum of Religious Colonial Art, the Museum of Contemporary Art, the Museum of the Interoceanic Canal, and the national institutes of culture and music.

Religion

The overwhelming majority of Panamanians are Roman Catholic, accounting for almost 80 percent of the population. Although the Constitution recognizes Catholicism as the religion of the great majority, Panama has no official religion. Minority religions in Panama include Protestantism (12 percent), Islam (4.4 percent), the Bahá'í Faith (1.2 percent), Buddhism (at least 1 percent), Greek Orthodox, Judaism, and Hinduism (less than one percent each).

The Jewish community in Panama, with over 10,000 members, is by far the largest in the region (including Central America, Colombia and the Caribbean). Jewish immigration began in the late 19th century, and there are synagogues in Panama City, as well as two Jewish schools. Within Latin America, Panama has one of the largest Jewish communities in proportion to its population, surpassed only by Uruguay and Argentina. Panama's communities of Muslims, East Asians, and South Asians are also among the largest.

Panama City hosts a Bahá'í House of Worship, one of only eight in the world. Completed in 1972, it is perched on a high hill facing the canal, and is constructed of local mud laid in a pattern reminiscent of Native American fabric designs.

Notes

- ↑ CIA, Panama World Factbook.

- ↑ Panama Population 2019 World Population Review. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 World Economic Outlook Database: Panama International Monetary Fund. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- ↑ Gini Index World Bank. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- ↑ History of the Panama Railroad The Panama Railroad. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- ↑ Panama Canal Authority, Panama Canal History—The French Canal Construction. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- ↑ Panama Canal Authority, Panama Canal History—American Canal Construction. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- ↑ Noam Chomsky, The invasion of Panama What Uncle Sam Really Wants, 1992. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Buckley, Kevin. Panama: The Whole Story. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992. ISBN 0671778765.

- LeFeber, Walter. The Panama Canal: A Crisis in Historical Perspective. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989. ISBN 0195061926.

- Lindsay-Poland, John. Emperors in the Jungle: The Hidden History of the U.S. in Panama. American encounters/global interactions. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003. ISBN 0822330989.

- Murillo, Luis E. The Noriega Mess: The Drugs, the Canal, and Why America Invaded. Berkeley, CA: Video-Books, 1995. ISBN 0923444025.

External links

All links retrieved November 18, 2022.

- (Spanish) The President of Panama

- (Spanish) Ministry of Economics and Finance

- (Spanish) Ministry of External Relations

- Embassy of Panama in the U.S.

- Panama Tourism Bureau

- Panama Canal Authority

Belize · Costa Rica · El Salvador · Guatemala · Honduras · Nicaragua · Panama

Andorra · Angola · Argentina · Bolivia · Brazil · Cape Verde · Chile · Colombia · Costa Rica · Côte d'Ivoire · Cuba · Dominican Republic · Ecuador · El Salvador · France · Guatemala · Guinea-Bissau · Haiti · Holy See · Honduras · Italy · Mexico · Moldova · Monaco · Mozambique · Nicaragua · Panama · Paraguay · Peru · Philippines · Portugal · Romania · San Marino · São Tomé and Príncipe · Senegal · Sovereign Military Order of Malta · Spain · Timor-Leste · Uruguay · Venezuela

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.