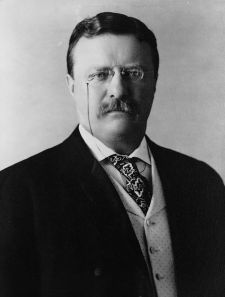

Theodore Roosevelt

| Term of office | September 14, 1901 – March 3, 1909 |

| Preceded by | William McKinley |

| Succeeded by | William Howard Taft |

| Date of birth | October 27, 1858 |

| Place of birth | New York City, New York |

| Date of death | January 6, 1919 |

| Place of death | Oyster Bay, New York |

| Spouse | Alice Hathaway Lee Roosevelt (married 1880–1884), Edith Carow Roosevelt (married 1886–1919) |

| Political party | Republican |

Theodore ("Teddy") Roosevelt (born Theodore Roosevelt Jr.) (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919) was a Nobel Peace Prize winner, distinguished naval historian, conservationist, governor of New York, U.S. vice president, and twenty-sixth president of the United States, succeeding President William McKinley upon his assassination on September 6, 1901.

Roosevelt was the fifth cousin of the later President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and the uncle of Eleanor Roosevelt, who would be first lady. Inaugurated at age 42, Roosevelt became the youngest sitting president. By force of will Roosevelt overcame a sickly childhood and took particular pride in leading what he called the "strenuous life." Roosevelt gained national recognition with his heroic assault leading the Rough Riders on San Juan Hill in Cuba during the Spanish American War and was noted for his big-game hunting expeditions into the American West, Africa, and South America.

Roosevelt's appreciation of nature, notwithstanding the indiscriminate slaughter that characterized hunting expeditions of the time, led to some of the most progressive conservation measures of any U.S. administration. As president Roosevelt signed legislation adding five national parks and 18 national monuments, as well as protecting extensive land preserves for public use. Roosevelt's presidency fostered great irrigation projects and the construction of the historic Panama Canal to promote global commerce. A voracious reader and first-rate intellect, Roosevelt made notable contributions in paleontology, taxidermy, and ornithology, and brought an unprecedented energy and intellectual vigor to the presidency. Despite a privileged background Roosevelt was deeply concerned with the public welfare, and legislation during his presidency enabled millions to earn a fair wage, which he called the “Square Deal.”

Charting a more muscular role for the United States in world affairs, Roosevelt anticipated the emergence of the United States as a world power. A leading proponent of modern naval power, he borrowed a West African proverb, "speak softly but carry a big stick," to characterize a more confident and expansive U.S. diplomatic posture. Roosevelt's advocacy of international engagement laid the groundwork for America's entry, and the ultimate Allied victory, in World War I (and, arguably, World War II).

Roosevelt earned a posthumous Medal of Honor for his courage in battle and was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1906 for his mediation of the Russo-Japanese War—the first American to win a Nobel Prize in any category. Through his travels in Pacific West, Roosevelt presciently saw that the balance of commerce and international influence would shift from the Atlantic sphere to the Pacific Rim, declaring in 1903 that the "Atlantic era is now at the height of its development and must soon exhaust the resources at its command. The Pacific era, destined to be the greatest of all, is just at its dawn."

Childhood and Education

Roosevelt was born at 28 East 20th Street in the modern-day Gramercy section of New York City on October 27, 1858, as the second of four children of Theodore Roosevelt, Sr. (1831–1878) and Martha Bulloch (1834–1884). Theodore was younger than his sister Anna but older than his brother Elliott Roosevelt and his sister Corinne Roosevelt Robinson. His father was a New York City philanthropist, merchant, and partner in the glass-importing firm, Roosevelt and Son. Many at the time did not know that his father had paid someone else to fight in the war on his behalf. Brands (1998) points out that later, Theodore would “be troubled by his father's failure to serve” (19). However, Theodore always adored his father and tried to act as he would have wished. He missed his father bitterly after his death, especially his wise counsel (86). Martha Bulloch was a Southern belle from Georgia and had Confederate sympathies. On his mother's side, Theodore's uncle—Capt. James Dunwoody Bulloch—was a famous Confederate naval officer.

Sickly and asthmatic as a youngster, Roosevelt had to sleep propped up in bed or slouching in a chair during much of his early childhood, and had frequent ailments. Despite his illnesses, he was a hyperactive and oftentimes mischievous young man. His lifelong interest in zoology was first formed at age seven upon seeing a dead seal at a local market. After obtaining the seal's head, the young Roosevelt and two of his cousins formed what they called the "Roosevelt Museum of Natural History." Learning the rudiments of taxidermy, Roosevelt filled his makeshift museum with many animals that he caught, studied, and prepared for display. At age nine, he codified his observation of insects with a paper titled "The Natural History of Insects."

To combat his poor physical condition, his father compelled the young Roosevelt to take up exercise. To deal with bullies Roosevelt started boxing lessons. Two trips abroad also had a great effect on him. From 1869 to 1870 his family toured Europe. From 1872 to 1873 the Roosevelt family traveled in Egypt, the Holy Land, and spent several months in Dresden, Germany. Soon afterwards, he became a sporting and outdoor enthusiast, a hobby that would last a lifetime.

Brands (1998) argues that Roosevelt believed in heroes, partly from his wide reading, and transformed himself into the “hero” that he wanted to become. He cites Roosevelt’s “I felt a great admiration for men who were fearless and who could hold their own in the world, and I had a great desire to be like them” (28). His heroes, too, “knew how to comport themselves in the face of tragedy,” and Roosevelt tried to do the same (86).

Young "Teedie," as he was nicknamed as a child, was mostly home schooled by tutors. He matriculated at Harvard College in 1876. His father's death in 1878 was a tremendous blow, but Roosevelt redoubled his activities. He did well in science, philosophy, and rhetoric courses, but fared poorly in classical languages. He studied biology with great interest, and indeed was already an accomplished naturalist and published ornithologist. He had a photographic memory, and developed a life-long habit of devouring books, memorizing every detail. He was an unusually eloquent conversationalist, who throughout his life sought out the company of the smartest men and women. He could multitask in extraordinary fashion, dictating letters to one secretary and memoranda to another, while browsing through a book, an ability he shared with Napoleon Bonaparte.

While at Harvard, Roosevelt was: editor of the student newspaper, the Advocate; vice-president of the Natural History Club; member of the Porcellian Club; secretary of the Hasty Pudding Club; founder of the Finance Club along with Edward Keast; member of the Nuttall Ornithological Club; and runner-up in the Harvard boxing championship, losing to C.S. Hanks, the defending champion. The sportsmanship Roosevelt showed in that fight was long remembered.

He graduated Phi Beta Kappa and magna cum laude (21st of 177) from Harvard in 1880, and entered Columbia Law School. Finding law boring, however, Roosevelt researched and wrote his first major book, The Naval War of 1812 (1882). Presented with an opportunity to run for New York Assemblyman in 1881, he dropped out of law school to pursue his new goal of entering public life. He had a sense of duty. On his father's death bed, he told him that he intended to study hard and to “live like a brave Christian gentleman” (Brands, 86). From his visit to Germany, he gained an admiration for hard work and a sense of duty, about which he spoke many years later. He believed it better to try and not succeed than not to even try, “because there is no effort without error and shortcoming” [1]. Ambitious and self-confident, he was aware of his own faults.

Life in the Badlands

Roosevelt was an activist during his years in the Assembly, writing more bills than any other New York state legislator. His motive was to rid the country of corruption. Already a major player in state politics, in 1884, he attended the Republican National Convention and fought alongside the Mugwump reformers who opposed the Stalwarts; they lost to the conservative faction that nominated James G. Blaine. Refusing to join other Mugwumps in supporting Grover Cleveland, the Democratic nominee, he stayed loyal to the party and supported Blaine. During this convention Roosevelt also received attention for seconding an African American for the position of chairman.

His wife, Alice Hathaway Roosevelt and his mother both died on Valentine's Day that year, and in the same house, only two days after his wife gave birth to their only daughter, Alice Roosevelt Longworth. Roosevelt was distraught, writing in his diary, "the light has gone out of my life forever." He never mentioned Alice's name again (she was absent even from his autobiography) and did not allow others to speak of her in his presence. Later that year, he left the General Assembly and his infant daughter and moved to the Badlands of the Dakota Territory for the life of a rancher and lawman. This was his strategy for dealing with his personal tragedy, a type of therapy that would indeed work for him for eventually he felt able to remarry and returned to public life.

Living near the boomtown of Medora, North Dakota, Roosevelt learned to ride and rope, occasionally getting involved in fistfights and spent his time with the rough-and-tumble world of the final days of the American Old West. On one occasion, as a deputy sheriff, he hunted down three outlaws taking a stolen boat down the Little Missouri River, successfully taking them back overland to trial.

After the 1886–1887 winter wiped out Roosevelt's herd of cattle, and his $60,000 investment (together with those of his competitors), he returned to the eastern United States, where in 1885, he had purchased Sagamore Hill in Oyster Bay, New York. It would be his home and estate until his death. Roosevelt ran as the Republican candidate for mayor of New York City in 1886, coming in a distant third. Following the election, he went to London, marrying his childhood sweetheart, Edith Kermit Carow while there. They honeymooned in Europe, and Roosevelt took the time to climb Mont Blanc, leading only the third expedition to successfully reach the top. Roosevelt is the only president to have become a widower and remarry before becoming president.

In the 1880s, he gained recognition as a serious historian. Roosevelt's The Naval War of 1812 (1882) was the standard history for two generations, but his hasty biographies of Thomas Hart Benton (1887) and Governor Morris (1888) were not particularly successful. His major achievement was a four-volume history of the frontier, The Winning of the West (1889–1896), which had a notable impact on historiography as it presented a highly original version of the frontier thesis developed in 1893 by his friend Frederick Jackson Turner. His many articles in upscale magazines provided a much-needed income, as well as cementing a reputation as a major national intellectual. He was later elected president of the American Historical Association.

Return to public life

In the 1888 presidential election, Roosevelt campaigned for Benjamin Harrison in the Midwest. President Harrison appointed Roosevelt to the United States Civil Service Commission where he served until 1895. In his term, he vigorously fought the spoils system and demanded the enforcement of civil service laws. In spite of Roosevelt's support for Harrison's reelection bid in the presidential election of 1892, the eventual winner, Grover Cleveland (a Democrat), reappointed him to the same post.

In 1895, Roosevelt became president of the New York Board of Police Commissioners. During the two years that he held this post, Roosevelt radically changed the way a police department was run. Roosevelt required his officers to be registered with the board and to pass a physical fitness test. He also saw that telephones were installed in station houses. Always an energetic man, Roosevelt made a habit of walking officers' beats late at night and early in the morning to make sure that they were on duty. He also engaged a pistol expert to teach officers how to shoot their firearms. While serving on the board, Roosevelt also opened up job opportunities in the department to women and Jews for the first time.

Urged by Roosevelt's close friend, Congressman Henry Cabot Lodge, President William McKinley appointed Roosevelt as Assistant Secretary of the Navy in 1897. Roosevelt shared the views of his contemporary and friend, Alfred Thayer Mahan, who had organized his earlier War College lectures into his most influential book, The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783. Roosevelt advocated expanding the Navy into a service with a global reach. He campaigned for the modernization of the Navy and the reorganization of both the department and its officer corps. He also fought for an increase in ship-building capability warning that building modern ships would take years instead of the mere weeks of construction in the age of sail. Consciously, Roosevelt was instrumental in preparing the Navy for what he saw as an unavoidable conflict with Spain. Events would prove him right. During the Spanish-American War, the U.S. Navy would scour the globe in search of ships to support worldwide operations.

Upon the declaration of war in 1898, Roosevelt resigned from the Navy Department and, with the aid of U.S. Army Colonel Leonard Wood, organized the First U.S. National Cavalry (known as the Rough Riders) out of a diverse crew that ranged from cowboys from the Western territories to Ivy League chums from New York. The newspapers billed them as the "Rough Riders." Originally, Roosevelt held the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and served under Col. Wood, but after Wood was promoted to Brigadier General of Volunteer Forces, Roosevelt was promoted to full Colonel and put in control of the Rough Riders. Under his direct command, the Rough Riders became famous for their dual charges up Kettle Hill and at the Battle of San Juan Hill in July 1898, the battle being named after the latter hill.

Upon his return from Cuba, Roosevelt reentered New York state politics and was elected governor of New York in 1898. He made such a concerted effort to root out corruption and "machine politics" that Republican boss Thomas C. Platt forced him on McKinley as a running mate in the 1900 election to simplify their control of the state.

Vice Presidency

McKinley and Roosevelt won the presidential election of 1900, defeating William Jennings Bryan and Adlai E. Stevenson Sr.. At his inauguration on March 4, 1901, Roosevelt became the second youngest U.S. vice president (John C. Breckinridge, at 36, was the youngest) at the time of his inauguration. Roosevelt found the vice-presidency unfulfilling, and thinking that he had little future in politics, considered returning to law school after leaving office. On September 2, 1901, Roosevelt first uttered a sentence that would become strongly associated with his presidency, urging Americans to "speak softly and carry a big stick" during a speech at the Minnesota State Fair.

Presidency

McKinley was shot by an anarchist, Leon Czolgosz, on September 6, 1901, and died September 14, vaulting Roosevelt into the presidency. Roosevelt took the oath of office on September 14 in Ansley Wilcox House at Buffalo, New York. One of his first notable acts as president was to deliver a 20,000-word address to the United States House of Representatives on December 3, 1901, asking Congress to curb the power of trusts "within reasonable limits." For this, and subsequent actions, he has been called a "trust-buster."

As President, Roosevelt seemed to be everywhere at once. He took Cabinet members and friends on long, fast-paced hikes, boxed in the state rooms of the White House, romped with his children, and read voraciously. In 1908, he was permanently blinded in one eye during one of his boxing bouts, but this injury was kept from the public at the time.

In the presidential election of 1904, Roosevelt ran for president in his own right and won in a landslide victory, becoming only the second New Yorker elected to the presidency (Martin Van Buren was the first) by winning 336 of 476 Electoral votes, and 56.4 percent of the total popular vote.

Building on McKinley's effective use of the press, Roosevelt made the White House the center of news every day, providing interviews and photo opportunities. His children were almost as popular as he was, and their pranks and hijinks in the White House made headlines. His daughter, Alice Roosevelt Longworth, became the toast of Washington. When friends asked if he could rein in his elder daughter, Roosevelt said, "I can be President of the United States, or I can control Alice. I cannot possibly do both." In turn, Alice said of him that he always wanted to be "the bride at every wedding and the corpse at every funeral." His many enthusiastic interests and limitless energy, and his undying passion for justice and righteousness, gave him the confidence and intestinal fortitude to stand up for what was right, and not always popular. He was unflinching in the line of fire. As president, he reduced the national debt by over $90,000,000 and enabled legislation that extended employment opportunities, as he believed in a “square deal” for all Americans. “A square deal for everyman” was his one favorite formula (Brands, 509).

Growing split inside the Republican Party

Roosevelt certified William Howard Taft to be a genuine "progressive," in the U.S. presidential election of 1908, when Roosevelt pushed through the nomination of his uncharismatic Secretary of War. Taft easily defeated three-time candidate William Jennings Bryan. Taft sincerely considered himself a "progressive" because of his deep belief in "The Law" as the scientific device that should be used by judges to solve society's problems. Taft proved an inept politician, and lacked the energy and personal magnetism, not to mention the publicity devices, the dedicated supporters, and the broad base of public support that made Roosevelt so formidable. When Roosevelt realized that lowering tariffs would risk severe tensions inside the GOP (Grand Old Party, aka the Republican Party), pitting producers (manufacturers and farmers) against department stores and consumers, he stopped talking about the issue. Taft ignored the risks and tackled the tariff boldly, on the one hand encouraging reformers to fight for lower rates, then cutting deals with conservative leaders that kept overall rates high. The resulting Payne-Aldrich tariff of 1909 was too high for most reformers, but instead of blaming this on Senator Nelson Aldrich and big business, Taft took credit, calling it the best tariff ever. Again he had managed to alienate all sides. While the crisis was building inside the Republican Party, Roosevelt was touring Africa and Europe, so as to allow Taft to be his own man.

Unlike Roosevelt, Taft never attacked business or businessmen in his rhetoric. However, he was attentive to the law, so he launched 90 antitrust suits, including one against the largest corporation, U.S. Steel, for an acquisition that Roosevelt had personally approved. The upshot was that Taft lost the support of antitrust reformers (who disliked his conservative rhetoric), of big business (which disliked his actions), and of Roosevelt, who felt humiliated by his protégé.

Under the leadership of Senators Robert LaFollette of Wisconsin and Albert Beveridge of Indiana, Midwestern progressives increasingly became party insurgents, battling both Taft and the conservative wing of the Republican Party. The tariff issue initially brought the insurgents together, but they broadened their attack to cover a wide range of issues. In 1910, they cooperated with Democrats to reduce the power of Speaker Joseph Cannon, a key conservative. Roosevelt had always disliked Cannon, but respected his power and never attempted to undercut it. The insurgents were much bolder. In 1911, LaFollette created the National Progressive Republican League to defeat the power of political bossism at the state level, and to replace Taft at the national level. More trouble came when Taft dismissed Gifford Pinchot, a leading conservationist and close ally of Roosevelt. Pinchot alleged that Taft's Secretary of Interior Richard Ballinger was in league with big timber interests. Conservationists sided with Pinchot, as Taft alienated yet another vocal constituency.

Roosevelt, back from Europe, unexpectedly launched an attack on the federal courts, which deeply upset Taft. Not only had Roosevelt alienated big business, he was also attacking both the judiciary and the deep faith Republicans had in their judges (most of whom had been appointed by McKinley, Roosevelt, or Taft). In the 1910 Congressional elections, Democrats swept to power and Taft's reelection in the presidential election of 1912 was increasingly in doubt.

Progressive Party candidate in 1912

Late in 1911, Roosevelt finally broke with Taft and LaFollette and announced himself as a candidate for the Republican nomination. Most of LaFollette's supporters went over to Roosevelt, leaving the Wisconsin senator embittered. Roosevelt, stepping up his attack on judges, carried nine of the states with preferential primaries, LaFollette took two, and Taft only one. Most professional Republican politicians were supporting Taft, and they proved difficult to upset in non-primary states. In a decisive move, Taft's people purchased support of the corrupt politicians who represented the shadow Republican party in southern states. These states always voted Democratic in presidential elections, but their delegates had over 300 votes at the Republican National Convention. Taft's managers, led by Elihu Root beat back challenges to their southern delegations; Taft now had more delegates than Roosevelt, but not a clear-cut majority. Roosevelt's people had made similar purchases in the south in the presidential election of 1904, but this time the Rough Rider called foul. Not since the 1872 presidential election had there been a major schism in the Republican Party; Roosevelt himself in 1884 had refused to bolt the ticket even though he distrusted candidate James G. Blaine. Now, with the Democrats holding about 45 percent of the national vote, any schism would be fatal. Roosevelt's only hope at the convention was to form a "stop-Taft" alliance with LaFollette, but LaFollette hated Roosevelt too much to allow that. Unable to tolerate the personal humiliation he suffered at the hands of Taft and the Old Guard, and refusing to entertain the possibility of a compromise candidate, Roosevelt struck back hard. Outvoted, Roosevelt pulled his delegates off the convention floor and decided to form a third party.

Roosevelt, along with key allies such as Pinchot and Beveridge created the Progressive Party in 1912, structuring it as a permanent organization that would field complete tickets at the presidential and state level. It was popularly known as the "Bull Moose Party." At his Chicago convention Roosevelt cried out, "We stand at Armageddon and we battle for the Lord." The crusading rhetoric resonated well with the delegates, many of them long-time reformers, crusaders, activists, and opponents of politics as usual. Included in the ranks were Jane Addams and many other feminists and peace activists. The platform echoed Roosevelt's 1907–1908 proposals, calling for vigorous government intervention to protect the people from selfish interests.

The great majority of Republican governors, congressmen, editors, and local leaders refused to join the new party, even if they had supported Roosevelt before. Only five of the 15 most prominent progressive Republicans in the Senate endorsed the new party; three came out for Wilson. Many of Roosevelt's closest political allies supported Taft, including his son-in-law, Nicholas Longworth. Roosevelt's daughter Alice Roosevelt Longworth stuck with her father, causing a permanent chill in her marriage. For men like Longworth, expecting a future in politics, bolting the Republican Party ticket was simply too radical a step; for others, it was safer to go with Woodrow Wilson, and quite a few supporters of progressivism had doubts about the reliability of Roosevelt's beliefs.

Historians speculate that if the Bull Moose had only run a presidential ticket, it might have attracted many more Republicans willing to split their ballot. But the progressive movement was strongest at the state level, and, therefore, the new party had to field candidates for governor and state legislature. In Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the local Republican boss, at odds with state party leaders, joined Roosevelt's cause. In California, Governor Hiram Johnson and the Bull Moosers took control of the regular Republicans’ party; Taft was not even listed on the California ballot. Johnson became Roosevelt's running-mate. In most states, there were full Republican and Progressive tickets in the field, thus splitting the Republican vote. Roosevelt campaigned vigorously on the "Bull Moose" ticket. While campaigning in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, he was shot by saloonkeeper John Schrank in a failed assassination attempt on October 14, 1912. With the bullet still lodged in his chest, Roosevelt still delivered his scheduled speech. He was not seriously wounded, although his doctors thought it too dangerous to attempt to remove the bullet, and he carried it with him until he died.

The central problem faced by the Progressive Party was that the Democrats were more united and optimistic than they had been in years. The Bull Moosers fancied they had a chance to elect Roosevelt by drawing out progressive elements from both the Republican and Democratic parties. That dream evaporated in July, when the Democrats unexpectedly rejected party hacks and instead nominated their most articulate and prominent progressive, Woodrow Wilson. As the crusading governor of New Jersey, Wilson had attracted national attention. As a leading educator and political scientist, he qualified as the ideal "expert" to handle affairs of state. Wilson appealed to regular Democrats, to progressive Democrats, and to independent progressives of the sort Roosevelt was also targeting. At least half the nation's independent progressives flocked to Wilson's camp, both because of Wilson's policies and the expectation of victory. This left the Bull Moose Party high and dry. Roosevelt haters, such as LaFollette, also voted for Wilson instead of wasting their vote on Taft who could never win.

Roosevelt nonetheless conducted a vigorous national campaign, denouncing the way the Republican nomination had been "stolen." He bundled together his reforms under the rubric of "The New Nationalism" and stumped the country for a strong federal role in regulating the economy, and, especially, watching and chastising bad corporations and overruling federal and state judges who made unprogressive decisions. Wilson called for "The New Freedom," which emphasized individualism rather than the collectivism that Roosevelt was promoting. Once he was in office, however, Wilson, in practice, supported reforms that resembled Roosevelt's collectivism more than his own individualism. Taft, knowing he had no chance to win, campaigned quietly, emphasizing the superior role of judges over the demagogy of elected officials. The departure of the more extreme progressives left the conservatives even more firmly in control of the GOP, and many of the Old Guard leaders even distrusted Taft as a bit too progressive for their taste, especially on matters of antitrust and tariffs. Much of the Republican effort was designed to discredit Roosevelt as a dangerous radical, but people knew Roosevelt too well to buy that argument. The result was the weakest Republican effort in history.

The most serious problem faced by Roosevelt's third party was money. The business interests who usually funded Republican campaigns distrusted Roosevelt and either sat the election out, or supported Taft. Newspaper publisher Frank Munsey provided most of the funds, with large sums also given by George Perkins. Perkins was a divisive factor; a former official of U.S. Steel, he single-handedly removed the antitrust plank from the progressive platform. Radicals, such as Pinchot, deeply distrusted Perkins and Munsey, though, realizing the fledgling party depended on their deep pockets. Roosevelt, however, strongly backed Perkins, who remained as party chairman to the bitter end. A few newspapers endorsed Roosevelt, including the Chicago Tribune, but the great majority stood behind Taft or Wilson. Lacking a strong party press, the Bull Moosers had to spend most of their money on publicity.

Roosevelt succeeded in his main goal of punishing Taft; with 4.1 million votes (27 percent), he ran well ahead of Taft's 3.5 million (23 percent). However, Wilson's 6.3 million votes (42 percent) were enough to garner 435 electoral votes. Taft, with two small states, Vermont and Utah, had 8 electoral votes. Roosevelt had 88: Pennsylvania was his only Eastern state; in the Midwest, he carried Michigan, Minnesota, and South Dakota; in the West, California and Washington; in the South, none. The Democrats gained ten seats in the Senate, just enough to form a majority, and 63 new House seats to solidify their control there. Progressive statewide candidates trailed about 20 percent behind Roosevelt's vote. Almost all, including Albert Beveridge of Indiana, went down to defeat; the only governor elected was Hiram Johnson of California. A mere 17 Bull Moosers were elected to Congress, and perhaps 250 to local office. Outside California, there obviously was no real base to the party beyond the personality of Roosevelt himself.

Roosevelt had scored a second-place finish, but he trailed so far behind Wilson that everyone realized his party would never win the White House. With the poor performance at state and local levels in 1912, the steady defection of top supporters, the failure to attract any new support, and a pathetic showing in 1914, the Bull Moose Party disintegrated. Some leaders, such as Harold Ickes of Chicago, supported Wilson in 1916. Most followed Roosevelt back into the GOP, which nominated Charles Evans Hughes. The ironies were many: Taft had been Roosevelt's hand-picked successor in 1908 and the split between the two men was personal and bitter; if Roosevelt had supported a compromise candidate in 1912, the GOP would not have split, and probably would have won; if Roosevelt had just waited, he likely would have been nominated and elected in 1916, as a Republican. Roosevelt's schism allowed the conservatives to gain control of the Republican Party and left Roosevelt and his followers drifting in the wilderness.

Roosevelt and the First World War

Roosevelt was bitterly disappointed with the foreign policies of President Woodrow Wilson and his pacifist Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan. When World War I began in 1914, Roosevelt sympathized more with the Allies and demanded a harsher policy against Germany, especially regarding submarine warfare. In 1916, he campaigned energetically for Hughes and repeatedly denounced Irish-Americans and German-Americans, whose pleas for neutrality Roosevelt labeled as unpatriotic. He insisted that one had to be 100 percent American, not a "hyphenated-American." When the U.S. entered the war in 1917, Roosevelt sought to raise a volunteer division, but Wilson refused, perhaps because his famed publicity machine would upstage the White House. Roosevelt's attacks on Wilson helped the Republicans win control of Congress in the elections of 1918. Had Roosevelt remained healthy, he could have won the 1920 GOP nomination, but his health was broken by 1918 due to tropical disease.

Post-Presidency

On March 23, 1909, shortly after the end of his second term (but only full term) as president, Roosevelt left New York for a post-presidency hunting safari in Africa. The trip was sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution and the National Geographic Society and received worldwide media attention. Despite his commitment to conservation, his party killed over 6000 animals, including some white rhinos.

As an author, Roosevelt continued to write with great passion on subjects ranging from American foreign policy to the importance of the national park system. One of Roosevelt's more popular books, Through the Brazilian Wilderness, was about his expedition into the Brazilian jungle. After the election of 1912, Roosevelt went on the Roosevelt-Rondon Scientific Expedition, exploring the Brazilian jungle with Brazilian explorer Cândido Rondon. During this expedition, he discovered the Rio of Doubt, later renamed Rio Roosevelt in honor of the President. Roosevelt also caught a debilitating tropical disease that cut short his life. In all, Roosevelt wrote about 18 books, including his Autobiography, Rough Riders, and histories of the United States Naval Academy, ranching, and wildlife, which are still in use today.

Roosevelt was a great supporter of the Scouting movement, such that local Scout councils in Arizona and New York have been named for him.

On January 6, 1919, at the age of 60, Roosevelt died in his sleep of a coronary embolism at Oyster Bay, New York, and was buried in Young's Memorial Cemetery. Upon receiving word of his death, his son, Archie, sent a telegram to his siblings, stating simply, "The old lion is dead."

Personal life

Roosevelt was baptized in the family's Dutch Reformed church; he attended the Madison Square Presbyterian Church until the age of 16. Later in life, when Roosevelt lived at Oyster Bay he attended an Episcopal church with his wife. While in Washington, D.C., he attended services at Grace Reformed Church. As president, he firmly believed in the separation of church and state and thought it unwise to have “In God We Trust” on U.S. currency, because he thought it sacrilegious to put the name of the deity on something as common as money.

Roosevelt had a lifelong interest in pursuing what he called "the strenuous life." To this end, he exercised regularly and took up boxing, tennis, hiking, watercraft rowing, hunting, polo, and horseback riding. As governor of New York, he boxed with sparring partners several times a week, a practice he regularly continued as president until one blow detached his left retina, leaving him blind in that eye. Thereafter, he practiced jujitsu and continued as well his habit of skinny-dipping in the Potomac River during winter.

At the age of 22, Roosevelt married his first wife, 19-year-old Alice Hathaway Lee Roosevelt. Their marriage ceremony was held on October 27, 1880, at the Unitarian Church in Brookline, Massachusetts. Alice was the daughter of the prominent banker George Cabot Lee and Caroline Haskell Lee. The couple first met on October 18, 1878, at the residence of her next-door neighbors, the Saltonstalls. By Thanksgiving, Roosevelt had decided to marry Alice. He finally proposed in June 1879, though Alice waited another six months before accepting the proposal; their engagement was announced on Valentine's Day 1880. Alice Roosevelt died shortly after the birth of their first child, whom they also named Alice Lee Roosevelt Longworth. In a tragic coincidence, his mother died on the same day as his wife at the Roosevelt family home in Manhattan.

In 1886, he married Edith Carow. They had five children: Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., Kermit Roosevelt, Ethel Carow Roosevelt, Archibald Roosevelt, and Quentin Roosevelt. Although Roosevelt's father was also named Theodore Roosevelt, he died while the future president was still childless and unmarried, and the future President Roosevelt took the suffix of Sr. and subsequently named his son Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. Because Roosevelt was still alive when his grandson and namesake were born, said grandson was named Theodore Roosevelt III, and consequently the president's son retained the Jr. after his father's death.

Legacy

On January 16, 2001, President Bill Clinton posthumously awarded Theodore Roosevelt the Medal of Honor (highest U.S. honor), for his charge up San Juan Hill, in Cuba, during the Spanish-American War. The award was accepted on Roosevelt's behalf by his great-grandson, Tweed Roosevelt. The Roosevelts thus became one of only two father-son pairs to receive this honor. Roosevelt's eldest son, Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., was awarded the Medal of Honor for his heroism at Normandy, (France) during the D-Day invasion of June 6, 1944. The other pair was General Douglas MacArthur and his father, Civil War hero General Arthur MacArthur, Jr..

One of Roosevelt's most important accomplishments was the building of the Panama Canal. He was a firm believer in Captain Mahan's theory of sea power. His motivation for building the Panama Canal was to restore the Navy to be the best that it could be. "The canal,” Roosevelt said, "was the most important action done in foreign affairs during my Presidency. When no one would exercise efficient authority, I exercised it."

There were only five national parks when Theodore Roosevelt became president. During his presidency, he added five more parks and 18 national monuments. He wanted to preserve the beauty of the land for future generations, a concern that reflected his own interest in outdoor pursuits. Roosevelt earned a place for himself in the history of conservation. His passion for knowledge and for nature took him into Brazilian forests and to Africa's wide open spaces, and when mourning his first wife's death, it was ranching that enabled him to find a new interest in life. Author of 30 books, winner of a Nobel Peace Prize and of a posthumous Medal of Honor, he showed leadership in peace and in war.

Quotes

- "The credit belongs to those who are actually in the arena, who strive valiantly, who know the great enthusiasms, the great devotions, and spend themselves in a worthy cause; who, at the best, know the triumph of high achievement and who, at the worst, if they fail, fail while daring greatly so that their place shall never be with those cold timid souls who know neither victory nor defeat."

- "…the man who really counts in the world is the doer, not the mere critic—the man who actually does the work, even if roughly and imperfectly, not the man who only talks or writes about how it ought to be done."

- "I have a perfect horror of words that are not backed up by deeds."

- "I have never in my life envied a human being who led an easy life; I have envied a great many people who led difficult lives and led them well."

- "There are good men and bad men of all nationalities, creeds and colors; and if this world of ours is ever to become what we hope some day it may become, it must be by the general recognition that the man's heart and soul, the man's worth and actions, determine his standing."

- "There is not in all America a more dangerous trait than the deification of mere smartness unaccompanied by any sense of moral responsibility."

- "Far better is it to dare mighty things, to win glorious triumphs, even though checkered by failure…than to rank with those poor spirits who neither enjoy nor suffer much, because they live in a gray twilight that knows not victory nor defeat."

- "A thorough knowledge of the Bible is worth more than a college education."

- "Character, in the long run, is the decisive factor in the life of an individual and of nations alike."

- "Courtesy is as much a mark of a gentleman as courage."

- "Great thoughts speak only to the thoughtful mind, but great actions speak to all mankind."

- "If you could kick the person in the pants responsible for most of your trouble, you wouldn't sit for a month."

- "In a moment of decision the best thing you can do is the right thing. The worst thing you can do is nothing."

Presidential firsts

- Theodore Roosevelt was the first American to be awarded a Nobel Prize (in any category) in 1906, and he remains the only sitting president to win the Nobel Peace Prize (for his part in ending the Russo-Japanese War). Jimmy Carter won the award as a former president.

- First and only U.S. President to be awarded the Medal of Honor (posthumously in 2001), for his charge up San Juan Hill.

- First sitting U.S. President to make an official trip outside of the United States, visiting Panama to inspect the construction progress of the Panama Canal on November 9, 1906 [2].

- First President to appoint a Jew, Oscar S. Straus in 1906, as a Presidential Cabinet Secretary.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

References

- Beale, Howard K. Theodore Roosevelt and the Rise of America to World Power. Baltimore: John Hopkins Press, 1956. ASIN B0006AUN2E

- Blum, John Morton. The Republican Roosevelt, 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004. ISBN 0674763025

- Brands, H.W. TR: The Last Romantic. New York: Basic Books, 1998. ISBN 0465069584

- Cooper, John Milton. The Warrior and the Priest: Woodrow Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2004. ISBN 0674947517

- Dalton, Kathleen. Theodore Roosevelt: A Strenuous Life. New York: Knopf, 2002. ISBN 067944663X

- Gould, Lewis L. The Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1991. ISBN 0700604359

- Harbaugh, William Henry. The Life and Times of Theodore Roosevelt. New York: Oxford University Press, 1975. ISBN 0195198220

- Keller, Morton, ed. Theodore Roosevelt: A Profile. New York: Hill and Wang Publishers, 1963. ISBN 0809082705

- Maxwell, William, The Dawn of the Pacific Century: Implications for Three Worlds of Development New York: Transaction, 1991 ISBN 1560008865

- Morris, Edmund. The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt. New York: Random House Modern Library, 2001. ISBN 0375756787

- Morris, Edmund. Theodore Rex. New York: Random House Modern Library, 2002. ISBN 0812966007

- Mowry, George. The Era of Theodore Roosevelt and the Birth of Modern America, 1900–1912. New York: Harper. ASIN B0007G5S9A

- Mowry, George E. Theodore Roosevelt and the Progressive Movement. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1946. ASIN B0007E8ATW

- O'Toole, Patricia. When Trumpets Call: Theodore Roosevelt after the White House. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005. ISBN 0684864770

- Pringle, Henry F. Theodore Roosevelt: A Biography. Orlando, FL: Harvest, 2003. ISBN 0156028026

- Rhodes, James Ford. The McKinley and Roosevelt Administrations, 1897–1909. New York: Macmillan, 1922. ASIN B0006AIUJW

External links

All links retrieved April 30, 2023.

- Almanac of Theodore Roosevelt

- Theodore Roosevelt Association

- Works by Theodore Roosevelt. Project Gutenberg

- Index of T. Roosevelt Etexts

- Theodore Roosevelt Inaugural Address

- State of the Union addresses for 1901, 1902, 1903, 1904, 1905, 1906, 1907, and 1908

- Theodore Roosevelt Papers at the Library of Congress

- Theodore Roosevelt: His Life and Times on Film (LOC)

- Sagamore Hill National Historic Site

- Ron Schuler's Parlour Tricks: Teddy

| ||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.