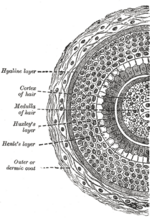

Hair, a filamentous, often pigmented, outgrowth from the skin, is found only on mammals and often in a high-density of filaments per unit area. These threadlike fibers protrude from the outer layer of the skin, the epidermis, and grow from hair follicles in the inner portion of the skin, the dermis. Each fiber comprises nonliving cells whose primary component is long chains (polymers) of amino acids forming the protein keratin. The keratinized cells arise from cell division in the hair matrix at the base of a hair follicle and are tightly packed together. Keratins also are a principle part of the cells in the nails, feathers, hooves, horny tissues, and tooth enamel of mammals.

In humans, hair, with its variety of colors, textures, shape, length, density, and other qualities, adds to individual uniqueness and provides an aesthetic quality for others to see and appreciate.

The hair of non-human species is commonly referred to as fur when in sufficient density. The effectiveness of fur in temperature regulation is evident in its use in such mammals as polar bears, and its perceived beauty is evident not only in its historical use in fur coats, but also in the popularity of pet grooming. There also are breeds of cats, dogs, and mice bred to have little or no visible fur.

Although many other life forms, especially insects, show filamentous outgrowths, these are not considered "hair" according to the accepted meaning of the term. The projections on arthropods, such as insects and spiders are actually insect bristles, not hair. Plants also have "hairlike" projections.

Hair follicles

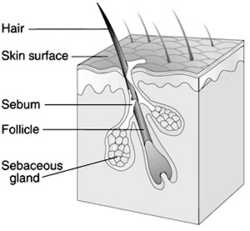

The epidermis through which each individual hair projects is largely made up of epithelium and lacks blood vessels, while the underlying dermis, wherein reside the hair follicles from which each hair grows, comprises not only the follicles but also connective tissue, blood vessels, sweat glands, and other structures.

A hair follicle is a cavity in the skin that contains the root of a hair and grows hair by packing old cells together. Attached to the follicle is a sebaceous gland, a tiny sebum-producing gland found most everywhere. but not on the palms, lips, and soles of the feet. The thicker the density of hair, the more sebaceous glands are found.

At the base of the follicle is a large structure called the papilla. The papilla is made up mainly of connective tissue and a capillary loop. Cell division in the papilla is either rare or non-existent. Around the papilla is the hair matrix, a collection of epithelial cells often interspersed with melanocytes (cells that produce melanin). Cell division in the hair matrix is responsible for the cells that will form the major structures of the hair fiber and the inner root sheath. The hair matrix epithelium is one of the fastest growing cell populations in the human body. Some forms of chemotherapy or radiotherapy that kill dividing cells may lead to temporary hair loss, by their action on this rapidly dividing cell population. The papilla is usually ovoid or pear shaped with the matrix wrapped completely around it, except for a short stalk-like connection to the surrounding connective tissue, which provides access for the capillary.

Also attached to the follicle is a tiny bundle of muscle fibers called the arrector pili, which is responsible for causing the follicle and hair to become more perpendicular to the surface of the skin, causing the follicle to protrude slightly above the surrounding skin. This process results in "goose bumps" (or goose flesh). Stem cells are located at the junction of the arrector and the follicle and are principally responsible for the ongoing hair production during a process known as the anagen stage.

Certain species of Demodex mites live in the hair follicles of mammals (including those of humans), where they feed on sebum.

Hair shafts are not permanent, but continually grow and are replaced. In some species, such as humans and cats, each follicle appears to grow independent of the others, but in other species, such as the rat, mouse, and rabbit, the replacement pattern is undulant. The average growth rate of hair follicles on the scalp of humans is .04 cm per day.

Hair grows in cycles of various phases. Anagen is the growth phase; catagen is the regressing phase; and telogen is the resting, or quiescent, phase. Each phase has several morphologically and histologically distinguishable sub-phases. Prior to the start of cycling is a phase of follicular morphogenesis (formation of the follicle). There is also a shedding phase, or exogen, that is independent of anagen and telogen, in which one of several hairs from a single follicle exits. Normally up to 90 percent of the hair follicles are in anagen phase while, 10–14 percent are in telogen, and 1–2 percent in catagen. The cycle's length varies on different parts of the body. For eyebrows, the cycle is completed in around 4 months, while it takes the scalp 3–4 years to finish; this is the reason eyebrow hairs have a fixed length, while hairs on the head seem to have no length limit. Growth cycles are controlled by a chemical, signal-like, epidermal growth factor.

Hair growth cycle times in humans:

- Scalp: The time these phases last varies from person to person. Different hair color and follicle shape effects the timings of these phases.

- anagen phase, 2–3 years (occasionally much longer)

- catagen phase, 2–3 weeks

- telogen phase, around 3 months

- Eyebrows, etc:

- anagen phase, 4–7 months

- catagen phase, 3–4 weeks

- telogen phase, about 9 months

Hair in non-human species

The presence of hair is a unique mammalian characteristic, helping mammals to maintain a stable core body temperature. Hair and endothermy have aided mammals in inhabiting a wide diversity of environments, from desert to polar, both nocturnally and diurnally.

In non-human species, the body hair, when in sufficient amounts, is commonly referred to as fur, or as the pelage (like the term plumage in birds). Wool is the fiber derived from the fur of animals of the Caprinae family, principally sheep, but the hair of certain species of other mammals, such as goats, alpacas, llamas, and rabbits may also be called wool.

The amount of hair reflects the environment to which the mammal is adapted. Polar bears have thick, water-repellent fur with hollow hairs that trap heat well. Whales have very limited hair in isolated areas, thus reducing drag in the water. Instead, they maintain internal temperatures with a thick layer of blubber (vascularized fat).

No mammals have hair that is naturally blue or green in color. Some cetaceans (whales, dolphins and porpoises), along with the mandrills, appear to have shades of blue skin. Many mammals are indicated as having blue hair or fur, but in all cases it will be found to be a shade of gray. The two-toed sloth can seem to have green fur, but this color is caused by algal growths.

An animal's coat of fur may consist of short ground hair, long guard hair, and, in some cases, medium awn hair. Not all mammals have fur; animals without fur may be referred to as "naked," as in "naked mole rat."

Fur usually consists of two main layers:

- Ground hair or underfur—the bottom layer consisting of wool hairs, which tend to be shorter, flattened, curly, and denser than the top layer.

- Guard hair—the top layer consisting of longer straight shafts of hair that stick out through the underfur. This is usually the visible layer for most mammals and contains most of the pigmentation.

Human hair

Types of hair

Humans have three different types of hair:

- Lanugo, the fine hair that covers nearly the entire body of fetuses.

- Vellus hair, the short, fine, "peach fuzz" body hair that grows in most places on the human body in both sexes.

- Terminal hair, the fully developed hair, which is generally longer, coarser, thicker, and darker than vellus hair.

Body hair

Humans have significantly less covering of body hair than is characteristic for primates. Historically, several ideas have been advanced to describe the reduction of human body hair. All were faced with the same problem: There is no fossil record of human hair to back up the conjectures, nor to determine exactly when the feature developed. Savanna Theory suggests that nature selected humans for shorter and thinner body hair as part of a set of adaptations to the warm plains of the savanna, including bipedal locomotion and an upright posture. Another theory for the thin body hair on humans proposes that Fisherian runaway sexual selection played a role here (as well as in the selection of long head hair), possibly in conjunction with neoteny, with the more juvenile appearing females being selected by males as more desirable. The Aquatic Ape Hypothesis posits that sparsity of hair is an adaptation to an aquatic environment, but it has little support among scientists and very few aquatic mammals are, in fact, hairless.

In reality, there may be little to explain in terms of amount of hair, but rather an issue of type of hair. Humans, like all primates, are part of a trend toward sparser hair in larger animals. According to Schwartz and Rosenblum (1981), the density of human hair follicles on the skin is actually about what one would expect for an animal of the same size. The outstanding question is why so much of human hair is short, underpigmented, vellus hair rather than terminal hair.

Head hair

Head hair is a type of hair that is grown on the head (sometimes referring directly to the scalp). This is the most noticeable of all human hair, which can grow longer than on most mammals and is more dense than most hair found elsewhere on the body. The average human head (an average scalp measures approximately 120 square inches or 770 cm²) has about 100,000 hair follicles (Gray 2003). Each follicle can grow about 20 individual hairs in a person's lifetime (About 2007). Average hair loss is around 100 strands a day. The absence of head hair is termed alopecia, commonly known as baldness.

Anthropologists speculate that the functional significance of long head hair may be adornment. Long lustrous hair may be a visible marker for a healthy individual. With good nutrition, waist length hair—approximately 1 meter or 39 inches long—would take around 48 months, or about 4 years, to grow.

Hair density is related to both race and hair color. Caucasians have the highest hair density, with an average growth rate, while Asians have the lowest density but fastest growing hair, and Africans have medium density and slowest growing hair.

Average number of head hairs (Caucasian) (Stevens 2007)

| color | number of hairs | diameter | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blonde | 146,000 | 1⁄1500th to 1⁄500th inch | 17 to 51 micrometers |

| Black | 110,000 | 1⁄400th to 1⁄250th inch | 64 to 100 micrometers |

| Brown | 100,000 | ||

| Red | 86,000 | ||

Growth

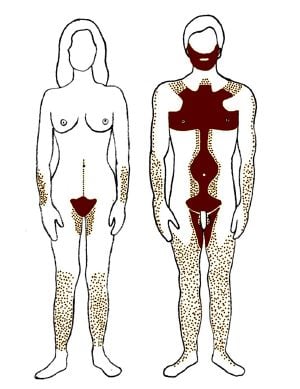

Different parts of the human body feature different types of hair. From childhood onward, vellus hair covers the entire human body regardless of sex or race except in the following locations: The lips, the nipples, the palms of hands, the soles of feet, certain external genital areas, the navel, and scar tissue. The density of the hairs (in hair follicles per square centimeter) varies from one person to another.

The rising level of male hormones (androgens) during puberty causes a transformation process of vellus hair into terminal hair on several parts of the male body. The hair follicles respond to androgens, primarily testosterone and its derivatives; the hair in these locations can be thus termed androgenic hair. The rate of hair growth and the weight of the hairs increase. However, different areas respond with different sensitivities. As testosterone levels increase, the sequence of appearance of androgenic hair reflects the gradations of androgen sensitivity. The pubic area is most sensitive, and heavier hair usually grows there first in response to androgens.

Areas on the human body that develop terminal hair growth due to rising androgens in both sexes, men and women, are the underarms and the pubic area. In contrast, normally only men grow androgenic hair in other areas. There is a sexual dimorphism in the amount and distribution of androgenic hair, with males having more terminal hair (particularly facial hair, chest hair, abdominal hair, and hair on legs and arms) and females having more vellus hair, which is less visible. The genetic disposition determines the sex-dependent and individual rising of androgens and therefore the development of androgenic hair.

Increased body hair on women following the male pattern can be referred to as hirsutism. An excessive and abnormal hair growth on the body of males and females is defined as hypertrichosis. Considering an individual occurrence of body hair as abnormal does not implicitly depend on medical indications, but also on cultural and social attitudes.

Individual hairs alternate periods of growth and dormancy. During the growth portion of the cycle, hair follicles are long and bulbous, and the hair advances outward at about a third of a millimeter per day. After three to six months, body hair growth stops (the pubic and armpit areas having the longest growth period), the follicle shrinks, and the root of the hair grows rigid. Following a period of dormancy, another growth cycle starts, and eventually a new hair pushes the old one out of the follicle from beneath. Head hair, by comparison, grows for a long duration and to a great length before being shed. The rate of growth is approximately 15 millimeters, or about ⅝ inch, per month.

Texture

Hair texture is measured by the degree of which one's hair is either fine or coarse, which in turn varies according to the diameter of each individual hair. There are commonly four major categories recognized for hair texture: Fine, medium, coarse, and wiry. Within the four texture ranges hair can also have thin, medium, or thick density and it can be straight, curly, wavy, or kinky. Hair conditioner will also alter the ultimate equation. Hair can also be textured if straighteners, crimpers, curlers, and so forth are used to style hair. Also, a hairdresser can change the hair texture with the use of special chemicals.

According to Ley (1999), the diameter of human hair ranges from 17 to 181 µm (millionths of a meter).

Aging

Older people tend to develop gray hair because the pigment in the hair is lost and the hair becomes colorless. Gray hair is considered to be a characteristic of normal aging. The age at which this occurs varies from person to person, but in general nearly everyone 75 years or older has gray hair, and in general men tend to become gray at younger ages than women.

It should be noted however, that gray hair in itself is not actually gray. The gray head of hair is a result of the contrast between the dark and the white/colorless hair forming an overall "gray" appearance to the observer. As such, people starting out with very pale blond hair usually develop white hair instead of gray hair when aging. Red hair usually does not turn gray with age; rather it becomes a sandy color and afterward turns white. In fact, the gray or white appearance of individual hair fibers is a result of light scattering from air bubbles in the central medula of the hair fiber.

Some degree of scalp hair loss or thinning generally accompanies aging in both males and females, and it is estimated that half of all men are affected by male pattern baldness by the time they are 50 (Springfield 2005). The tendency toward baldness is a trait shared by a number of other primate species, and is thought to have evolutionary roots.

It is commonly claimed that hair and nails will continue growing for several days after death. This is a myth; the appearance of growth is actually caused by the retraction of skin as the surrounding tissue dehydrates, making nails and hair more prominent.

Pathological impacts on hair

Drugs used in cancer chemotherapy frequently cause a temporary loss of hair, noticeable on the head and eyebrows, because they kill all rapidly dividing cells, not just the cancerous ones. Other diseases and traumas can cause temporary or permanent loss of hair, either generally or in patches.

The hair shafts may also store certain poisons for years, even decades, after death. In the case of Col. Lafayette Baker, who died July 3, 1868, use of an atomic absorption spectrophotometer showed the man was killed by white arsenic. The prime suspect was Wally Pollack, Baker's brother-in-law. According to Dr. Ray A. Neff, Pollack had laced Baker's beer with it over a period of months, and a century or so later minute traces of arsenic showed up in the dead man's hair. Mrs. Baker's diary seems to confirm that it was indeed arsenic, as she writes of how she found some vials of it inside her brother's suit coat one day.

Cultural attitudes

Head hair

The remarkable head hair of humans has gained an important significance in nearly all present societies as well as any given historical period throughout the world. The haircut has always played a significant cultural and social role.

In ancient Egypt, head hair was often shaved, especially among children, as long hair was uncomfortable in the heat. Children were often left with a long lock of hair growing from one part of their heads, the practice being so common that it became the standard in Egyptian art for artists to depict children as always wearing this "sidelock." Many adult men and women kept their heads permanently shaved for comfort in the heat and to keep the head free of lice, while wearing a wig in public.

In ancient Greece and ancient Rome, men and women already differed from each other through their haircuts. The head hair of a woman was long and generally pulled back into a chignon hairstyle. Many dyed their hair red with henna and sprinkled it with gold powder, often adorning it with fresh flowers. Men’s hair was short and even occasionally shaved. In Rome, hairdressing became ever more popular and the upper classes were attended to by slaves or visited public barber shops.

The traditional hair styling in some parts of Africa also gives interesting examples of how people dealt with their head hair. The Maasai warriors tied the front hair into sections of tiny braids, while the back hair was allowed to grow to waist length. Women and non-warriors, however, shaved their heads. Many tribes dyed the hair with red earth and grease; some stiffened it with animal dung.

Contemporary social and cultural conditions have constantly influenced popular hair styles. From the seventeenth century into the early nineteenth century, it was the norm for men to have long hair, often tied back into a ponytail. Famous long-haired men include Oliver Cromwell and George Washington. During his younger years, Napoleon Bonaparte had a long and flamboyant head of hair. Before World War I, men generally had longer hair and beards. The trench warfare between 1914 and 1918 exposed men to lice and flea infestations, which prompted the order to cut hair short, establishing a norm that has persisted.

However it has also been advanced that short hair on men has been enforced as a means of control, as shown in the military and police and other forces that require obedience and discipline. Additionally, slaves and defeated armies were often required to shave their heads, in both pre-medieval Europe and China.

Growing and wearing long hair is a lifestyle practiced by millions worldwide. It was almost universal among women in Western culture until World War I. Many women in conservative Pentecostal groups abstain from trimming their hair after conversion (and some have never had their hair trimmed or cut at all since birth). The social revolution of the 1960s led to a renaissance of unchecked hair growth.

Hair length is measured from the front scalp line on the forehead, up over the top of the head and down the back to the floor. Standard milestones in this process of hair growing are classic length (midpoint on the body, where the buttocks meet the thighs), waist length, hip length, knee length, ankle/floor length, and even beyond. It takes about seven years, including occasional trims, to grow one's hair to waist length. Terminal length varies from person to person according to genetics and overall health.

Body hair

The attitudes towards hair on the human body also vary between different cultures and times. In some cultures, profuse chest hair on men is a symbol of virility and masculinity; other societies display a hairless body as a sign of youthfulness.

In ancient Egypt, people regarded a completely smooth, hairless body as the standard of beauty. An upper class Egyptian woman took great pains to ensure that she did not have a single hair on her body, except for the top of her head (and even this was often replaced with a wig (Dersin 2004). The ancient Greeks later adopted this smooth ideal, considering a hairless body to be representative of youth and beauty. This is reflected in Greek female sculptures which do not display any pubic hair. Islam stipulates many tenets with respect to hair, such as the covering of hair by women and the removal of armpit and pubic hair.

In Western societies, it became a public trend during the late twentieth century, particularly for women, to reduce or to remove their body hair.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- About. 2007. About: Hair loss. About.com, a part of The New York Times company.

- Dersin, D., P. Piccione, and T. M. Dousa. 2004. On the Banks of the Nile : Egypt 3050-30 B.C.E. What Life Was Like. London: Caxton, under license from Time-Life Books. ISBN 1844471446

- Gray, J. 2003. The world of hair: Hair facts. P&G Hair Care Research Center. Retrieved March 2, 2007.

- Ley, B. 1999. Diameter of a human hair. In G. Elert, ed., The Physics Factbook (online). Retrieved March 2, 2007.

- Schwartz, G. G., and L. A. Rosenblum. 1981. Allometry of primate hair density and the evolution of human hairlessness. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 55(1): 9-12.

- Springfield News Leader. 2005. Uncovering the bald truth about hair loss. Springfield News Leader, May 10, 2005. Retrieved March 2, 2007.

- Stenn, K. S., and R. Paus. 2001. Controls of hair follicle cycling. Physiological Reviews 81(1): 449–494.

- Stevens, C. 2007. Hair: An introduction. The Trichological Society. Retrieved March 2, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.