Fat

| Types of Fats in Food |

|---|

|

| See Also |

Chemically speaking, fats are triglycerides, uncharged esters of the three-carbon alcohol glycerol that are solid at room temperature (20° C). Triglycerides that are liquid at room temperature are referred to as oils. Triglycerides belong to a diverse class of biological molecules called lipids, which are generally water-insoluble but highly soluble in organic solvents.

Known primarily as efficient energy stores in animals, triglycerides can be mobilized to meet the energy needs of the organism. Some plant species, such as avocados, olives, and nuts, have substantial amounts of triglycerides in seeds or fruits that serve as energy reserves for the next generation.

However, triglycerides play a variety of biological roles. Concentrated fat deposits in adipose tissue insulate organs against shock and help to maintain a stable body temperature. Fat-soluble vitamins are involved in activities ranging from blood clotting to bone formation and can only be digested and transported when bonded to triglycerides.

The consumption of fats in the diet requires personal responsibility and discipline, as there is diversity in the health impacts of different triglycerides. While triglycerides are an important part of the diet of most heterotrophs, high levels of certain types of triglycerides in the bloodstream have been linked to atherosclerosis (the formation of plaques within the arteries) and, by extension, to the risk of heart disease and stroke. However, the health risk depends on the chemical composition of the fats consumed.

High levels of saturated fats and trans fats increase the amount of low-density lipoprotein (LDL), a transport molecule that carries fat and cholesterol from the liver, while lowering the amount of high-density lipoprotein (HDL), which clears cholesterol from the bloodstream. Consumption of saturated fats, which are common in some dairy products (such as butter), meat, and poultry, correlates with heart disease, stroke, and even some cancers.

In contrast, monounsaturated fats and omega-3 and omega-6 fats may work to prevent heart disease by lowering the LDL:HDL ratio. A diet with vegetable oils, fatty fish (such as salmon), and nuts are important in this respect.

Thus, discipline and taking personal responsibility are important in order to consume foods that are healthy for the body, while limiting consumption of food that may taste good, but be unhealthy. Social responsibility is also called for in terms of a more equitable distribution of healthy food to those in need.

The chemical structure of fats

Triglycerides consist of three fatty acid chains bonded to a glycerol backbone. Fatty acids are a class of compounds that consist of a long hydrocarbon chain and a terminal carboxyl group (-COOH). A triglyceride is an ester of glycerol; i.e., a molecule formed from a condensation (water-releasing) reaction between the three hydroxyl (-OH) groups of glycerol and the carboxyl groups of the three fatty acid molecules.

Fatty acids are distinguished by two important characteristics: (1) chain length and (2) degree of unsaturation. The chemical properties of triglycerides are thus determined by their particular fatty acid components.

Chain length

Fatty acid chains in naturally occurring triglycerides are typically unbranched and range from 14 to 24 carbon atoms, with 16- and 18-carbon lengths being the most common. Fatty acids found in plants and animals are usually composed of an even number of carbon atoms, due to the biosynthetic process in these organisms. Bacteria, however, possess the ability to synthesize odd- and branched-chain fatty acids. Consequently, ruminant animal fat, such as in cattle, contains significant proportions of branched-chain fatty acids, due to the action of bacteria in the rumen.

Fatty acids with long chains are more susceptible to intermolecular forces of attraction (in this case, van der Waals forces), raising their melting point. Long chains also yield more energy per molecule when metabolized.

Degree of unsaturation

Fatty acids may also differ in the number of hydrogen atoms that branch off of the chain of carbon atoms:

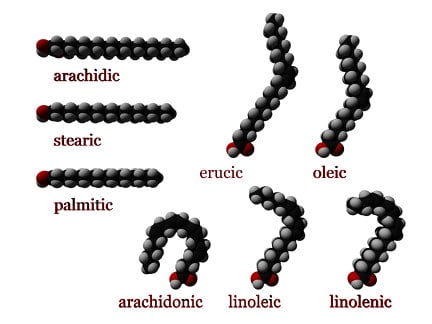

- When each carbon atom in the chain is bonded to two hydrogen atoms, the fatty acid is said to be saturated. Saturated fatty acids do not contain any double bonds between carbon atoms, because the carbon molecules are "saturated” with hydrogen; that is, they are bonded to the maximum number of hydrogen atoms.

- Monounsaturated fatty acids contain one double bond near the middle of the chain, creating a "kink" in the chain. One of the carbon atoms, bonded to only one hydrogen atom, forms a double bond with a neighboring carbon atom.

- Polyunsaturated fatty acids may contain between two and six double bonds, resulting in multiple "kinks." As the degree of unsaturation increases, the melting points of polyunsaturated fatty acids become lower.

The double bonds in unsaturated fatty acids may occur either in a cis or trans isomer, depending on the geometry of the double bond. In the cis conformation, the hydrogens are on the same side of the double bond, whereas in the trans conformation, they are on the opposite side.

Types of fats and their chemical properties

Naturally occurring fats contain varying proportions of saturated and unsaturated fatty acids, which in turn determine their relative energy content and melting point:

- Saturated fats, such as butter and lard, contain a high percentage of saturated fatty acids. The straight hydrocarbon chains of saturated fatty acids can stack themselves in a closely packed arrangement. Thus, saturated fats freeze easily and are typically solid at room temperature.

- Unsaturated fats, such as olive oil, which contains a high percentage of monounsaturated fatty acids, have lower melting points than saturated fats. The "kinks" created by the double bonds in unsaturated fatty acids prevent tight packing and rigidity. They also decrease intermolecular forces between the molecules, making it more difficult for unsaturated fats in the “cis” formation to freeze; thus, they are typically liquid at room temperature. Since an unsaturated fat contains fewer carbon-hydrogen bonds than a saturated fat with the same number of carbon atoms, unsaturated fats will yield slightly less energy during metabolism than saturated fats with the same number of carbon atoms.

- Omega-3 fats contain polyunsaturated fatty acids with a double bond three carbons away from the methyl carbon (at the omega end of the chain), whereas omega-6 fatty acids have a double bond six carbons away from the methyl carbon. They are found in salmon and other fatty fish, and to a lesser degree in walnuts and tofu.

- Natural sources of unsaturated fatty acids are rich in the cis isomer described above. In contrast, trans fats are popular with manufacturers of processed foods because they are less vulnerable to rancidity and more solid at room temperature than cis fats. However, trans fats reduce the fluidity (and functionality) of cell membranes. Trans fats have been associated with many health problems, but their biochemistry is poorly understood.

Fats function as long-term energy stores

Triglycerides play an important role in metabolism as highly concentrated energy stores; when metabolized, they yield more than twice as much energy as carbohydrates and proteins (approximately nine kcal/g versus four kcal/g). Triglycerides make such efficient energy stores because they are (1) highly reduced and (2) nearly anhydrous (because they are relatively nonpolar, they do not need to be stored in hydrated form).

In animals, a type of loose connective tissue called adipose contains adipocytes, specialized cells that form and store droplets of fat. Depending on the animal's current physiological conditions, adipocytes either store fat derived from the diet and liver or degrade stored fat to supply fatty acids and glycerol to the circulation. When energy is needed, stored triglycerides are broken down to release glucose and free fatty acids. The glycerol can be converted to glucose, another energy source, by the liver. The hormone glucagon signals the breakdown of the triglycerides by hormone-sensitive lipases to release free fatty acids. The latter combine with albumin, a protein in blood plasma, and are carried in the bloodstream to sites of utilization, such as heart and skeletal muscle.

In the intestine, triglycerides ingested in the diet are split into glycerol and fatty acids (this process is called lipolysis), which can then move into blood vessels. The triglycerides are rebuilt in the blood from their fragments and become constituents of lipoproteins, which deliver the fatty acids to and from adipocytes.

Other roles include insulation, transport, and biosynthesis

The fat deposits collected in adipose tissue can also serve to cushion organs against shock, and layers under the skin (called subcutaneous fat) can help to maintain body temperature. Subcutaneous fat insulates animals against the cold because of the low rate of heat transfer in fat, a property especially important for animals living in cold waters or climates, such as whales, walruses, and bears.

The class of fat-soluble vitamins—namely, Vitamins A, D, E, and K—can only be digested, absorbed, and transported in conjunction with fat molecules. Vitamin A deficiency leads to night blindness and is required by young animals for growth, while Vitamin D is involved in the bone formation of growing animals, Vitamin E is an important antioxidant, and Vitamin K is required for normal blood clotting.

Dietary fats are sources of the essential fatty acids linoleate and linolenate, which cannot be synthesized internally and must be ingested in the diet; they are the starting point for the synthesis of various other unsaturated fatty acids. Twenty-carbon polyunsaturated fatty acids, most commonly arachidonic acid (AA) in humans, are also precursors of the eicosanoids, which are known as local hormones because they are short-lived, altering the activity of the cell in which they are synthesized and in nearby cells.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Donatelle, R. J. 2005. Health: The Basics, 6th edition. San Francisco, CA: Pearson.

- Krogh, D. 2005. Biology: A Guide to the Natural World, 3rd edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

- Purves, W., D. Sadava, G. Orians, and H. C. Heller. 2004. Life: The Science of Biology, 7th edition. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer.

- Stryer, L. 1995. Biochemistry, 4th edition. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.