Dome

A dome (from Latin domus) is an architectural element similar to the hollow upper half of a sphere. There is significant overlap with the term cupola, which may refer either to a dome or to a structure on top of a dome. The precise definition of a dome has been a matter of controversy and there are a wide variety of forms and specialized terms to describe them.

Domes have a long architectural lineage that extends back into prehistory. Domes were built in ancient Mesopotamia, and they have been found in Persian, Hellenistic, Roman, and Chinese architecture in the ancient world, as well as among a number of indigenous building traditions throughout the world. Dome structures were common in both Byzantine architecture and Sasanian architecture, which influenced that of the rest of Europe and Islam, respectively, in the Middle Ages.

Domes have been constructed over the centuries from mud, snow, stone, wood, brick, concrete, metal, glass, and plastic. Advancements in mathematics, materials, and production techniques resulted in new dome types. The symbolism associated with domes includes both mortuary and celestial aspects. The domes of the modern world can be found over religious buildings, legislative chambers, sports stadiums, and a variety of functional structures. Regardless of the function of the building, the dome itself continues to inspire a connection to the heavens and the eternal realm.

Etymology

The English word "dome" ultimately derives from the ancient Greek and Latin domus ("house"), which, up through the Renaissance, labeled a revered house, such as a Domus Dei, or "House of God," regardless of the shape of its roof. This is reflected in the uses of the Italian word duomo, the German/Icelandic/Danish word dom ("cathedral"), and the English word dome as late as 1656, when it meant a "Town-House, Guild-Hall, State-House, and Meeting-House in a city." The French word dôme came to acquire the meaning of a cupola vault, specifically, by 1660. This French definition gradually became the standard usage of the English dome in the eighteenth century as many of the most impressive Houses of God were built with monumental domes, and in response to the scientific need for more technical terms.[1]

Definitions

Across the ancient world, curved-roof structures that would today be called domes had a number of different names reflecting a variety of shapes, traditions, and symbolic associations:

To the naive eye of men uninterested in construction, the dome, it must be realized, was first of all a shape and then an idea. As a shape (which antedated the beginnings of masonry construction), it was the memorable feature of an ancient, ancestral house. It is still a shape visualized and described by such terms as hemisphere, beehive, onion, melon, and bulbous. In ancient times it was thought of as a tholos, pine cone, omphalos, helmet, tegurium, kubba, kalube, maphalia, vihdra, parasol, amalaka tree, cosmic egg, and heavenly bowl. While the modern terms are purely descriptive, the ancient imagery both preserved some memory of the origin of the domical shape and conveyed something of the ancestral beliefs and supernatural meanings associated with its form.[1]

The shapes were derived from traditions of pre-historic shelters made from various impermanent pliable materials and were only later reproduced as vaulting in more durable materials.[1] The hemispherical shape often associated with domes today derives from Greek geometry and Roman standardization, but other shapes persisted, including a pointed and bulbous tradition inherited by some early Islamic mosques.[1]

Modern academic study of the topic has been controversial and confused by inconsistent definitions, such as those for cloister vaults and domical vaults. Dictionary definitions of the term "dome" are often general and imprecise; for example, "a large hemispherical roof or ceiling."[2]

The word "cupola" is another word for "dome," usually used for a small dome upon a roof or turret.[3]

Sometimes called "false" domes, corbel domes achieve their shape by extending each horizontal layer of stones inward slightly farther than the lower one until they meet at the top.[4] "True" domes are said to be those whose structure is in a state of compression, with constituent elements of wedge-shaped voussoirs, the joints of which align with a central point. The validity of this is unclear, as domes built underground with corbelled stone layers are in compression from the surrounding earth.[5]

The fields of engineering and architecture have lacked common language for domes, with engineering focused on structural behavior and architecture focused on form and symbolism.[6] Additionally, new materials and structural systems in the twentieth century have allowed for large dome-shaped structures that deviate from the traditional compressive structural behavior of masonry domes.

Elements

A dome can rest directly upon a rotunda wall, a drum, or a system of squinches or pendentives used to accommodate the transition in shape from a rectangular or square space to the round or polygonal base of the dome. The dome's apex may be closed or may be open in the form of an oculus, which may itself be covered with a roof lantern and cupola.

Materials

The earliest domes in the Middle East were built with mud-brick and, eventually, with baked brick and stone. In the Middle East and Central Asia, domes and drums constructed from mud brick and baked brick were sometimes covered with brittle ceramic tiles on the exterior to protect against rain and snow.[7]

Domes of wood allowed for wide spans due to the relatively light and flexible nature of the material and were the normal method for domed churches by the seventh century, although most domes were built with the other less flexible materials. Wooden domes were protected from the weather by roofing, such as copper or lead sheeting.[8]

Brick domes were the favored choice for large-space monumental coverings until the [[Industrial Revolution], due to their convenience and dependability. The new building materials of the nineteenth century and a better understanding of the forces within structures from the twentieth century opened up new possibilities. Iron and steel beams, steel cables, and pre-stressed concrete eliminated the need for external buttressing and enabled much thinner domes. Whereas earlier masonry domes may have had a radius to thickness ratio of 50, the ratio for modern domes can be in excess of 800. The lighter weight of these domes not only permitted far greater spans, but also allowed for the creation of large movable domes over modern sports stadiums.[9]

Acoustics

Because domes are concave from below, they can reflect sound and create echoes. A dome may have a "whispering gallery" at its base that at certain places transmits distinct sound to other distant places in the gallery.[10]

The half-domes over the apses of Byzantine churches helped to project the chants of the clergy.[11] Although this can complement music, it may make speech less intelligible, leading Francesco Giorgi in 1535 to recommend vaulted ceilings for the choir areas of a church, but a flat ceiling filled with as many coffers as possible for where preaching would occur.[12]

Cavities in the form of jars built into the inner surface of a dome may serve to compensate for this interference by diffusing sound in all directions, eliminating echoes while creating a "divine effect in the atmosphere of worship." The material, shape, contents, and placement of these cavity resonators determine the effect they have: reinforcing certain frequencies or absorbing them.[12]

Symbolism

According to E. Baldwin Smith, from the late Stone Age the dome-shaped tomb was used as a reproduction of the ancestral, god-given shelter made permanent as a venerated home of the dead. The instinctive desire to do this resulted in widespread domical mortuary traditions across the ancient world, from the stupas of India to the tholos tombs of Iberia. By Hellenistic and Roman times, the domical tholos had become the customary cemetery symbol.[1]

Domes and tent-canopies were also associated with the heavens in Ancient Persia and the Hellenistic-Roman world. A dome over a square base reflected the geometric symbolism of those shapes. The circle represented perfection, eternity, and the heavens. The square represented the earth. The distinct symbolism of the heavenly or cosmic tent stemming from the royal audience tents of Achaemenid and Indian rulers was adopted by Roman rulers in imitation of Alexander the Great, becoming the imperial baldachin. This probably began with Nero, whose "Golden House" also made the dome a feature of palace architecture.[1]

The dual sepulchral and heavenly symbolism was adopted by early Christians in both the use of domes in architecture and in the ciborium, a domical canopy like the baldachin used as a ritual covering for relics or the church altar. The celestial symbolism of the dome, however, was the preeminent one by the Christian era.[1]

In the early centuries of Islam, domes were closely associated with royalty. A dome built in front of the mihrab of a mosque, for example, was at least initially meant to emphasize the place of a prince during royal ceremonies. Over time such domes became primarily focal points for decoration or the direction of prayer. The use of domes in mausoleums can likewise reflect royal patronage or be seen as representing the honor and prestige that domes symbolized, rather than having any specific funerary meaning.[13] The wide variety of dome forms in medieval Islam reflected dynastic, religious, and social differences as much as practical building considerations.[8]

Types

Cloister vault

Cloister vaults, also called domical vaults (a term sometimes also applied to sail vaults),[14] polygonal domes, coved domes, gored domes, segmental domes (a term sometimes also used for saucer domes), paneled vaults, or pavilion vaults,[15] are domes that maintain a polygonal shape in their horizontal cross section. The component curved surfaces of these vaults are called severies, webs, or cells.[16] The earliest known examples date to the first century B.C.E., such as the Tabularium of Rome from 78 B.C.E. Others include the Baths of Antoninus in Carthage (145–160) and the Palatine Chapel at Aachen (thirteenth – fourteenth century).[17] The most famous example is the Renaissance octagonal dome of Filippo Brunelleschi over the Florence Cathedral.

Sail dome

Sail domes, also called sail vaults, handkerchief vaults,[3] domical vaults (a term sometimes also applied to cloister vaults), pendentive domes (a term that has also been applied to compound domes), or Bohemian vaults.[18] can be thought of as pendentives that, rather than merely touching each other to form a circular base for a drum or compound dome, smoothly continue their curvature to form the dome itself. The dome gives the impression of a square sail pinned down at each corner and billowing upward.[3]

Sail domes are based upon the shape of a hemisphere and are not to be confused with elliptic parabolic vaults, which appear similar but have different characteristics. In addition to semicircular sail vaults there are variations in geometry such as a low rise to span ratio or covering a rectangular plan. Sail vaults of all types have a variety of thrust conditions along their borders, which can cause problems, but have been widely used from at least the sixteenth century.

Saucer dome

Also called segmental domes (a term sometimes also used for cloister vaults), or calottes,[3] these have profiles of less than half a circle. Because they reduce the portion of the dome in tension, these domes are strong but have increased radial thrust. Many of the largest existing domes are of this shape.

Masonry saucer domes, because they exist entirely in compression, can be built much thinner than other dome shapes without becoming unstable. The trade-off between the proportionately increased horizontal thrust at their abutments and their decreased weight and quantity of materials may make them more economical, but they are more vulnerable to damage from movement in their supports.[19]

Compound dome

Also called domes on pendentives or pendentive domes (a term also applied to sail vaults), compound domes have pendentives that support a smaller diameter dome immediately above them, as in the Hagia Sophia, or a drum and dome, as in many Renaissance and post-Renaissance domes, with both forms resulting in greater height.

Ellipsoidal dome

The ellipsoidal dome is a surface formed by the rotation around a vertical axis of a semi-ellipse. Like other "rotational domes" formed by the rotation of a curve around a vertical axis, ellipsoidal domes have circular bases and horizontal sections and are a type of "circular dome" for that reason.

Braced dome

A single or double layer space frame in the form of a dome, a braced dome is a generic term that includes ribbed, Schwedler, three-way grid, lamella or Kiewitt, lattice, and geodesic domes.[20] The different terms reflect different arrangements in the surface members. Braced domes often have a very low weight. Often prefabricated, their component members can either lie on the dome's surface of revolution, or be straight lengths with the connecting points or nodes lying upon the surface of revolution. Single-layer structures are called frame or skeleton types and double-layer structures are truss types, which are used for large spans. When the covering also forms part of the structural system, it is called a stressed skin type. The formed surface type consists of sheets joined at bent edges to form the structure.

Crossed-arch dome

One of the earliest types of ribbed vault, the first known examples of a crossed-arch dome are found in the Great Mosque of Córdoba in the tenth century. Rather than meeting in the center of the dome, the ribs characteristically intersect one another off-center, forming an empty polygonal space in the center. Geometry is a key element of the designs, with the octagon being perhaps the most popular shape used. Whether the arches are structural or purely decorative remains a matter of debate. Examples are found in Spain, North Africa, Armenia, Iran, France, and Italy.[21]

Geodesic dome

Geodesic domes are the upper portion of geodesic spheres. They are composed of a framework of triangles in a polyhedron pattern. The structures are named for geodesics and are based upon geometric shapes such as icosahedrons, octahedrons, or tetrahedrons.[22][23] Such domes can be created using a limited number of simple elements and joints and efficiently resolve a dome's internal forces. Although not first invented by Buckminster Fuller, they are associated with him because he designed many geodesic domes and patented them in the United States.[9]

Umbrella dome

Also called gadrooned, fluted, organ-piped, and ribbed, as well as pumpkin, melon, and parachute,[3] scalloped, or lobed domes,[24] umbrella domes are a type of dome divided at the base into curved segments, which follow the curve of the elevation.[3] "Fluted" may refer specifically to this pattern as an external feature, such as was common in Mamluk Egypt.[23] The "ribs" of a dome are the radial lines of masonry that extend from the crown down to the springing. The central dome of the Hagia Sophia uses the ribbed method, which accommodates a ring of windows between the ribs at the base of the dome. The central dome of St. Peter's Basilica also uses this method.

Hemispherical dome

The hemispherical dome is a surface formed by the rotation around a vertical axis of a semicircle. Like other "rotational domes" formed by the rotation of a curve around a vertical axis, hemispherical domes have circular bases and horizontal sections and are a type of "circular dome" for that reason. According to E. Baldwin Smith, it was a shape likely known to the Assyrians, defined by Greek theoretical mathematicians, and standardized by Roman builders.[1]

Onion dome

Bulbous domes bulge out beyond their base diameters, offering a profile greater than a hemisphere. An onion dome is a greater than hemispherical dome with a pointed top in an ogee profile.[23] They are found in the Near East, Middle East, Persia, and India and may not have had a single point of origin. Their appearance in northern Russian architecture predates the Tatar occupation of Russia and so is not easily explained as the result of that influence.

They became popular in the second half of the fifteenth century in the Low Countries of Northern Europe, possibly inspired by the finials of minarets in Egypt and Syria, and developed in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in the Netherlands before spreading to Germany, becoming a popular element of the baroque architecture of Central Europe. German bulbous domes were also influenced by Russian and Eastern European domes.[25]

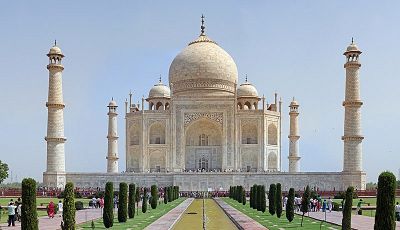

The examples found in various European architectural styles are typically wooden. Examples include Kazan Church in Kolomenskoye and the Brighton Pavilion by John Nash. In Islamic architecture, they are typically made of masonry, rather than timber, with the thick and heavy bulging portion serving to buttress against the tendency of masonry domes to spread at their bases. The Taj Mahal is a famous example.[23]

Oval dome

An oval dome is a dome of oval shape in plan, profile, or both. The earliest oval domes were used by convenience in corbelled stone huts as rounded but geometrically undefined coverings, and the first examples in Asia Minor date to around 4000 B.C.E. The geometry was eventually defined using combinations of circular arcs, transitioning at points of tangency. If the Romans created oval domes, it was only in exceptional circumstances. The Roman foundations of the oval plan Church of St. Gereon in Cologne point to a possible example.

Domes in the Middle Ages also tended to be circular, though the church of Santo Tomás de las Ollas in Spain has an oval dome over its oval plan. Other examples of medieval oval domes can be found covering rectangular bays in churches. Oval plan churches became a type in the Renaissance and popular in the Baroque style.[4]

Although the ellipse was known, in practice, domes of this shape were created by combining segments of circles. A sub-type with the long axis having a semicircular section is called a Murcia dome, as in the Chapel of the Junterones at Murcia Cathedral.

Paraboloid dome

A paraboloid dome is a surface formed by the rotation around a vertical axis of a sector of a parabola. Like other "rotational domes" formed by the rotation of a curve around a vertical axis, paraboloid domes have circular bases and horizontal sections and are a type of "circular dome" for that reason.

History

Early history and simple domes

Cultures from pre-history to modern times constructed domed dwellings using local materials. Although it is not known when the first dome was created, sporadic examples of early domed structures have been discovered. The earliest discovered may be four small dwellings made of Mammoth tusks and bones, dating from 19,280 – 11,700 B.C.E.[26]

The creation of relatively simple dome-like structures has been documented among various indigenous peoples around the world. The wigwam was made by Native Americans using arched branches or poles covered with grass or hides. The Efé people of central Africa construct similar structures, using leaves as shingles. Another example is the igloo, a shelter built from blocks of compact snow and used by the Inuit, among others. The Himba people of Namibia construct "desert igloos" of wattle and daub for use as temporary shelters at seasonal cattle camps, and as permanent homes by the poor.[27]

Corbelled stone domes have been found from the Neolithic period in the ancient Near East, and in the Middle East to Western Europe from antiquity. The kings of Achaemenid Persia held audiences and festivals in domical tents derived from the nomadic traditions of central Asia.[1] Simple domical mausoleums existed in the Hellenistic period. The remains of a large domed circular hall in the Parthian capital city of Nyssa has been dated to perhaps the first century C.E., showing "the existence of a monumental domical tradition in Central Asia that had hitherto been unknown and which seems to have preceded Roman Imperial monuments or at least to have grown independently from them."[28]

Persian domes

Persian architecture likely inherited an architectural tradition of dome-building dating back to the earliest Mesopotamian domes. An ancient tradition of royal audience tents representing the heavens was translated into monumental stone and brick domes due to the invention of the squinch, a reliable method of supporting the circular base of a heavy dome upon the walls of a square chamber. Domes were built as part of royal palaces, castles, caravansaries, and temples, among other structures.

The area of north-eastern Iran was, along with Egypt, one of two areas notable for early developments in Islamic domed mausoleums, which appear in the tenth century.[13] The Samanid Mausoleum in Transoxiana dates to no later than 943 and is the first to have squinches create a regular octagon as a base for the dome, which then became the standard practice.

The Seljuk Empire's notables built tomb-towers, called "Turkish Triangles," as well as cube mausoleums covered with a variety of dome forms. Seljuk domes included conical, semi-circular, and pointed shapes in one or two shells. The domed enclosure of the Jameh Mosque of Isfahan, built in 1086-1087 by Nizam al-Mulk, was the largest masonry dome in the Islamic world at that time, had eight ribs, and introduced a new form of corner squinch with two quarter domes supporting a short barrel vault. In 1088 Tāj-al-Molk, a rival of Nizam al-Mulk, built another dome at the opposite end of the same mosque with interlacing ribs forming five-pointed stars and pentagons.

Beginning in the Ilkhanate, Persian domes achieved their final configuration of structural supports, zone of transition, drum, and shells, and subsequent evolution was restricted to variations in form and shell geometry. Characteristic of these domes are the use of high drums and several types of discontinuous double-shells, and the development of triple-shells and internal stiffeners occurred at this time. The large, bulbous, fluted domes on tall drums that are characteristic of fifteenth century Timurid architecture were the culmination of the Central Asian and Iranian tradition of tall domes with glazed tile coverings in blue and other colors.[8]

The domes of the Safavid dynasty (1501–1732) are characterized by a distinctive bulbous profile and are considered the last generation of Persian domes. An exaggerated style of onion dome on a short drum, as can be seen at the Shah Cheragh (1852–1853), first appeared in the Qajar period. Domes have remained important in modern mausoleums, and domed cisterns and icehouses remain common sights in the countryside.

Chinese domes

Very little has survived of ancient Chinese architecture, due to the extensive use of timber as a building material. Brick and stone vaults used in tomb construction have survived, and the corbeled dome was used, rarely, in tombs and temples.[29]

The earliest true domes found in Chinese tombs were shallow cloister vaults, called simian jieding, derived from the Han use of barrel vaulting. Unlike the cloister vaults of western Europe, the corners are rounded off as they rise.[30] These four-sided domes used small interlocking bricks and enabled a square space near the entrance of a tomb large enough for several people that may have been used for funeral ceremonies. The Lei Cheng Uk Han Tomb, found in Hong Kong in 1955, has a design common among Eastern Han dynasty (25 C.E. – 220 C.E.) tombs in South China: a barrel vaulted entrance leading to a domed front hall with barrel vaulted chambers branching from it in a cross shape.

During the Three Kingdoms period (220–280), the "cross-joint dome" (siyuxuanjinshi) was developed under the Wu and Western Jin dynasties south of the Yangtze River, with arcs building out from the corners of a square room until they met and joined at the center. These domes were stronger, had a steeped angle, and could cover larger areas than the relatively shallow cloister vaults. Over time, they were made taller and wider. There were also corbel vaults, called diese, although these are the weakest type.[30]

Roman and Byzantine domes

Domes reached monumental size in the Roman Imperial period. Roman baths played a leading role in the development of domed construction in general, and monumental domes in particular. Modest domes in baths dating from the second and first centuries B.C.E. are seen in Pompeii, in the cold rooms of the Terme Stabiane and the Terme del Foro.[31]

The growth of domed construction increased under Emperor Nero and the Flavians in the first century C.E., and during the second century. Centrally-planned halls become increasingly important parts of palace and palace villa layouts beginning in the first century, serving as state banqueting halls, audience rooms, or throne rooms.[32] The Pantheon, a temple in Rome completed by Emperor Hadrian as part of the Baths of Agrippa, is the most famous, best preserved, and largest Roman dome.[31] Segmented domes, made of radially concave wedges or of alternating concave and flat wedges, appear under Hadrian in the second century and most preserved examples of this style date from this period.[33]

In the third century, Imperial mausoleums began to be built as domed rotundas, rather than as tumulus structures or other types, following similar monuments by private citizens. The technique of building lightweight domes with interlocking hollow ceramic tubes further developed in North Africa and Italy in the late third and early fourth centuries.[34] In the fourth century, Roman domes proliferated due to changes in the way domes were constructed, including advances in centering techniques and the use of brick ribbing.[33] The material of choice in construction gradually transitioned during the fourth and fifth centuries from stone or concrete to lighter brick in thin shells.[32] Baptisteries began to be built in the manner of domed mausoleums during the fourth century in Italy. The octagonal Lateran baptistery or the baptistery of the Holy Sepulchre may have been the first, and the style spread during the fifth century.[1] By the fifth century, structures with small-scale domed cross plans existed across the Christian world.[32]

With the end of the Western Roman Empire, domes became a signature feature of the church architecture of the surviving Eastern Roman — or "Byzantine" — Empire. Sixth-century church building by the Emperor Justinian used the domed cross unit on a monumental scale, and his architects made the domed brick-vaulted central plan standard throughout the Roman east. This divergence with the Roman west from the second third of the sixth century may be considered the beginning of a "Byzantine" architecture.[32] Justinian's Hagia Sophia was an original and innovative design with no known precedents in the way it covers a basilica plan with dome and semi-domes.

"Cross-domed units," a more secure structural system created by bracing a dome on all four sides with broad arches, became a standard element on a smaller scale in later Byzantine church architecture.[11] The Cross-in-square plan, with a single dome at the crossing or five domes in a quincunx pattern, became widely popular in the Middle Byzantine period (c. 843–1204). Resting domes on circular or polygonal drums pierced with windows eventually became the standard style, with regional characteristics.[32]

In the Byzantine period, domes were normally hemispherical and had, with occasional exceptions, windowed drums. All of the surviving examples in Constantinople are ribbed or pumpkin domes, with the divisions corresponding to the number of windows. Roofing for domes ranged from simple ceramic tile to more expensive, more durable, and more form-fitting lead sheeting. Metal clamps between stone cornice blocks, metal tie rods, and metal chains were also used to stabilize domed construction.[11]

Arabic and Western European domes

The Syria and Palestine area has a long tradition of domical architecture, including wooden domes in shapes described as "conoid," or similar to pine cones. When the Arab Muslim forces conquered the region, they employed local craftsmen for their buildings and, by the end of the seventh century, the dome had begun to become an architectural symbol of Islam.[1] In addition to religious shrines, such as the Dome of the Rock, domes were used over the audience and throne halls of Umayyad palaces, and as part of porches, pavilions, fountains, towers and the calderia of baths.

Italian church architecture from the late sixth century to the end of the eighth century was influenced less by the trends of Constantinople than by a variety of Byzantine provincial plans. With the crowning of Charlemagne as a new Roman Emperor, Byzantine influences were largely replaced in a revival of earlier Western building traditions. Occasional exceptions include examples of early quincunx churches at Milan and near Cassino.[32] Another is the Palatine Chapel. Its domed octagon design was influenced by Byzantine models. It was the largest dome north of the Alps at that time.[22] Venice, Southern Italy, and Sicily served as outposts of Middle Byzantine architectural influence in Italy.[32]

The Great Mosque of Córdoba contains the first known examples of the crossed-arch dome type.[21] The use of corner squinches to support domes was widespread in Islamic architecture by the tenth and eleventh centuries.[32] After the ninth century, mosques in North Africa often have a small decorative dome over the mihrab. Egypt, along with north-eastern Iran, was one of two areas notable for early developments in Islamic mausoleums, beginning in the tenth century.[13] Fatimid mausoleums were mostly simple square buildings covered by a dome. Domes were smooth or ribbed and had a characteristic Fatimid "keel" shape profile.[29]

Domes in Romanesque architecture are generally found within crossing towers at the intersection of a church's nave and transept, which conceal the domes externally.[35] The Crusades, beginning in 1095, also appear to have influenced domed architecture in Western Europe, particularly in the areas around the Mediterranean Sea. The Knights Templar, headquartered at the site, built a series of centrally planned churches throughout Europe modeled on the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, with the Dome of the Rock also an influence. The use of pendentives to support domes in the Aquitaine region, rather than the squinches more typical of western medieval architecture, strongly implies a Byzantine influence.[14] Gothic domes are uncommon due to the use of rib vaults over naves, and with church crossings usually focused instead by a tall steeple, but there are examples of small octagonal crossing domes in cathedrals as the style developed from the Romanesque.[35]

Star-shaped domes found at the Moorish palace of the Alhambra in Granada, Spain, the Hall of the Abencerrajes (c. 1333–1391) and the Hall of the two Sisters (c. 1333–1354), are extraordinarily developed examples of muqarnas domes.[35] In the first half of the fourteenth century, stone blocks replaced bricks as the primary building material in the dome construction of Mamluk Egypt and, over the course of 250 years, around 400 domes were built in Cairo to cover the tombs of Mamluk sultans and emirs Dome profiles were varied, with "keel-shaped," bulbous, ogee, stilted domes, and others being used.

Russian domes

The multidomed church is a typical form of Russian church architecture that distinguishes Russia from other Orthodox nations and Christian denominations. Indeed, the earliest Russian churches, built just after the Christianization of Kievan Rus', were multi-domed, which has led some historians to speculate about how Russian pre-Christian pagan temples might have looked. Examples of these early churches are the 13-domed wooden Saint Sophia Cathedral in Novgorod (989) and the 25-domed stone Desyatinnaya Church in Kiev (989–996). The number of domes typically has a symbolical meaning in Russian architecture, for example 13 domes symbolize Christ with 12 New Testament Apostles, while 25 domes means the same with an additional 12 Prophets of the Old Testament.

Plentiful timber in Russia made wooden domes common and at least partially contributed to the popularity of onion domes, which were easier to shape in wood than in masonry. The earliest stone churches in Russia featured Byzantine style domes, however by the Early Modern era the onion dome had become the predominant form in traditional Russian architecture. Though the earliest preserved Russian domes of such type date from the sixteenth century, illustrations from older chronicles indicate they have existed since the late thirteenth century.

Russian domes are often gilded or brightly painted. A dangerous technique of chemical gilding using mercury had been applied on some occasions until the mid-nineteenth century, most notably in the giant dome of Saint Isaac's Cathedral. The more modern and safe method of gold electroplating was applied for the first time in gilding the domes of the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow.

Ottoman domes

The rise of the Ottoman Empire and its spread in Asia Minor and the Balkans coincided with the decline of the Seljuk Turks and the Byzantine Empire. Early Ottoman buildings, for almost two centuries after 1300, were characterized by a blending of Ottoman culture and indigenous architecture. The Byzantine dome form was adopted and further developed.[8] Ottoman architecture made exclusive use of the semi-spherical dome for vaulting over even very small spaces, influenced by the earlier traditions of both Byzantine Anatolia and Central Asia.

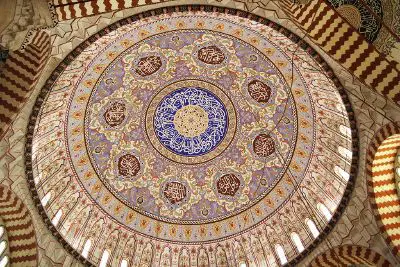

The Bayezid II Mosque (1501–1506) in Istanbul begins the classical period in Ottoman architecture, in which the great imperial mosques, with variations, resemble the former Byzantine basilica of Hagia Sophia in having a large central dome with semi-domes of the same span to the east and west. Hagia Sophia's central dome arrangement is largely reproduced in three Ottoman mosques in Istanbul: the Bayezid II Mosque, the Kılıç Ali Pasha Mosque, and the Süleymaniye Mosque. Other Imperial mosques in Istanbul added semi-domes to the north and south, doing away with the basilica plan, starting with the Şehzade Mosque and seen again in later examples such as the Sultan Ahmed I Mosque and the Yeni Cami.[36]

The classical period lasted into the seventeenth century but its peak is associated with the architect Mimar Sinan in the sixteenth century. In addition to large imperial mosques, he designed hundreds of other monuments, including medium-sized mosques such as the Mihrimah Sultan Mosque, Sokollu Mehmed Pasha Mosque, and Rüstem Pasha Mosque and the tomb of Suleiman the Magnificent, with its double-shell dome. The Süleymaniye Mosque, built from 1550 to 1557, has a main dome 53 meters high with a diameter of 26.5 meters.[36] At the time it was built, the dome was the highest in the Ottoman Empire when measured from sea level, but lower from the floor of the building and smaller in diameter than that of the nearby Hagia Sophia.

Italian Renaissance domes

Filippo Brunelleschi's octagonal brick domical vault over Florence Cathedral was built between 1420 and 1436 and the lantern surmounting the dome was completed in 1467. A combination of dome, drum, pendentives, and barrel vaults developed as the characteristic structural forms of large Renaissance churches following a period of innovation in the later fifteenth century. Florence was the first Italian city to develop the new style, followed by Rome and then Venice.[37] Brunelleschi's domes at San Lorenzo and the Pazzi Chapel established them as a key element of Renaissance architecture.[23] His plan for the dome of the Pazzi Chapel in Florence's Basilica of Santa Croce (1430–1452) illustrates the Renaissance enthusiasm for geometry and for the circle as geometry's supreme form. This emphasis on geometric essentials would be very influential.[35]

De re aedificatoria, written by Leon Battista Alberti around 1452, recommends vaults with coffering for churches, as in the Pantheon, and the first design for a dome at St. Peter's Basilica in Rome is usually attributed to him, although the recorded architect is Bernardo Rossellino. This would culminate in Bramante's 1505–1506 projects for a wholly new St. Peter's Basilica, marking the beginning of the displacement of the Gothic ribbed vault with the combination of dome and barrel vault, which proceeded throughout the sixteenth century. Bramante's initial design was for a Greek cross plan with a large central hemispherical dome and four smaller domes around it in a quincunx pattern. Work began in 1506 and continued under a succession of builders over the next 120 years. The dome was completed by Giacomo della Porta and Domenico Fontana.[37]

The Villa Capra, also known as "La Rotunda," was built by Andrea Palladio from 1565 to 1569 near Vicenza. Its highly symmetrical square plan centers on a circular room covered by a dome, and it proved highly influential on Georgian architects in eighteenth century England, architects in Russia, and architects in America, Thomas Jefferson among them. Palladio's two domed churches in Venice are San Giorgio Maggiore (1565–1610) and Il Redentore (1577–92), the latter built in thanksgiving for the end of a bad outbreak of plague in the city.[37]

South Asian domes

Domes first appeared in South Asia during the medieval era. They were generally constructed with stone, brick and mortar, and iron dowels and cramps. Centering was made from timber and bamboo. The use of iron cramps to join adjacent stones was known in Classical India, and was used at the base of domes for hoop reinforcement. The synthesis of styles created by this introduction of new forms to the Hindu tradition of trabeate construction created a distinctive architecture. Domes in pre-Mughal India have a standard squat circular shape with a lotus design and bulbous finial at the top, derived from Hindu architecture. Because the Hindu architectural tradition did not include arches, flat corbels were used to transition from the corners of the room to the dome, rather than squinches.[8] In contrast to Persian and Ottoman domes, the domes of Indian tombs tend to be more bulbous.[37]

The earliest examples include the half-domes of the late thirteenth century tomb of Balban and the small dome of the tomb of Khan Shahid, which were made of roughly cut material and would have needed covering surface finishes. Under the Lodi dynasty there was a large proliferation of tomb building, with octagonal plans reserved for royalty and square plans used for others of high rank, and the first double dome was introduced to India in this period. The first major Mughal building is the domed tomb of Humayun, built between 1562 and 1571 by a Persian architect. The central double dome covers an octagonal central chamber about 15 meters wide and is accompanied by small domed chattri made of brick and faced with stone.[38] Chatris, the domed kiosks on pillars characteristic of Mughal roofs, were adopted from their Hindu use as cenotaphs.[8]

The fusion of Persian and Indian architecture can be seen in the dome shape of the Taj Mahal: the bulbous shape derives from Persian Timurid domes, and the finial with lotus leaf base is derived from Hindu temples.[8] The Gol Gumbaz, or Round Dome, is one of the largest masonry domes in the world. It has an internal diameter of 41.15 meters and a height of 54.25 meters. The last major Islamic tomb built in India was the tomb of Safdar Jang (1753–54). The central dome is reportedly triple-shelled, with two relatively flat inner brick domes and an outer bulbous marble dome, although it may actually be that the marble and second brick domes are joined everywhere but under the lotus leaf finial at the top.[38]

Early modern period domes

In the early sixteenth century, the lantern of the Italian dome spread to Germany, gradually adopting the bulbous cupola from the Netherlands. Russian architecture strongly influenced the many bulbous domes of the wooden churches of Bohemia and Silesia and, in Bavaria, bulbous domes less resemble Dutch models than Russian ones. Domes like these gained in popularity in central and southern Germany and in Austria in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, particularly in the Baroque style, and influenced many bulbous cupolas in Poland and Eastern Europe in the Baroque period. However, many bulbous domes in eastern Europe were replaced over time in the larger cities during the second half of the eighteenth century in favor of hemispherical or stilted cupolas in the French or Italian styles.[25]

The construction of domes in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries relied primarily on empirical techniques and oral traditions rather than the architectural treatises of the times, which avoided practical details. This was adequate for domes up to medium size, with diameters in the range of 12 to 20 meters. Materials were considered homogeneous and rigid, with compression taken into account and elasticity ignored. The weight of materials and the size of the dome were the key references. Lateral tensions in a dome were counteracted with horizontal rings of iron, stone, or wood incorporated into the structure.[39]

Over the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, developments in mathematics and the study of statics led to a more precise formalization of the ideas of the traditional constructive practices of arches and vaults, and there was a diffusion of studies on the most stable form for these structures: the catenary curve. Robert Hooke, who first articulated that a catenary arch was comparable to an inverted hanging chain, may have advised Christopher Wren on how to achieve the crossing dome of St. Paul's Cathedral. Wren's structural system became the standard for large domes well into the nineteenth century.

The ribs in Guarino Guarini's San Lorenzo and Il Sidone were shaped as catenary arches.[37] The idea of a large oculus in a solid dome revealing a second dome originated with him. He also established the oval dome as a reconciliation of the longitudinal plan church favored by the liturgy of the Counter-Reformation and the centralized plan favored by idealists.

In the eighteenth century, the study of dome structures changed radically, with domes being considered as a composition of smaller elements, each subject to mathematical and mechanical laws and easier to analyze individually, rather than being considered as whole units unto themselves. Although never very popular in domestic settings, domes were used in a number of eighteenth century homes built in the Neo-Classical style.

Modern period domes

Nineteenth century historicism led to many domes being re-translations of the great domes of the past, rather than further stylistic developments, especially in sacred architecture.[35] New production techniques allowed for cast iron and wrought iron to be produced both in larger quantities and at relatively low prices during the Industrial Revolution. Excluding those that simply imitated multi-shell masonry, metal framed domes such as the elliptical dome of Royal Albert Hall in London (57 to 67 meters in diameter) and the circular dome of the Halle au Blé in Paris may represent the century's chief development of the simple domed form.[40]

The practice of building rotating domes for housing large telescopes in observatories was begun in the nineteenth century. Other large domes included exhibition buildings and functional structures such as gasometers and locomotive sheds. The "first fully triangulated framed dome" was built in Berlin in 1863 by Johann Wilhelm Schwedler and, by the start of the twentieth century, similarly triangulated frame domes had become fairly common.[40]

Domes built with steel and concrete were able to achieve very large spans.[23] In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Guastavino family, a father and son team who worked on the eastern seaboard of the United States, further developed the masonry dome, using tiles set flat against the surface of the curve and fast-setting Portland cement, which allowed mild steel bar to be used to counteract tension forces.[40] The thin domical shell was further developed with the construction by Walther Bauersfeld of two planetarium domes in Jena, Germany in the early 1920s. They consisting of a triangulated frame of light steel bars and mesh covered by a thin layer of concrete.[40] These are generally taken to be the first modern architectural thin shells; they are also considered the first geodesic domes. Geodesic domes have been used for radar enclosures, greenhouses, housing, and weather stations.[22]

The first permanent air supported membrane domes were the radar domes designed and built by Walter Bird after World War II. Their low cost eventually led to the development of permanent versions using teflon-coated fiberglass and by 1985 the majority of the domed stadiums around the world used this system. Tensegrity domes, patented by Buckminster Fuller in 1962, are membrane structures consisting of radial trusses made from steel cables under tension with vertical steel pipes spreading the cables into the truss form. They have been made circular, elliptical, and other shapes to cover stadiums from Korea to Florida.[41] The higher expense of rigid large span domes made them relatively rare, although rigidly moving panels is the most popular system for sports stadiums with retractable roofing.

Notes

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 Earl Baldwin Smith, The Dome: A Study in the History of Ideas (Princeton University Press, 1972, ISBN 978-0691003047).

- ↑ dome Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved December 5, 2024.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 John Fleming, Hugh Honour, and Nikolaus Pevsner (eds.), The Penguin Dictionary of Architecture: Fourth Edition (Penguin Books, 1991, ISBN 978-0140512410).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Santiago Huerta Fernandez, Oval Domes: History, Geometry and Mechanics In Kim Williams, (ed.), Nexus Network Journal 9(2) (2007): 211–248. Retrieved December 5, 2024.

- ↑ G.R.H. Wright, Building Technology, Volume 3: Construction (Brill, 2009, ISBN 9004177450).

- ↑ J.C. Chilton, "When is a dome not a dome? 20th century lightweight and tensile domes." In: Proceedings of the Annual Symposium of the Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain (Society of Architectural Historians of Great Britain, 2000), 131-146.

- ↑ Maryam Ashkan and Yahada Ahmad, Discontinuous Double-shell Domes through Islamic eras in the Middle East and Central Asia: History, Morphology, Typologies, Geometry, and Construction Nexus Network Journal 12(2) (2010): 287-319. Retrieved December 6, 2024.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 Andrew Peterson, Dictionary of Islamic Architecture (Routledge, 1996, ISBN 978-0415060844).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Mark Denny, Super Structures: The Science of Bridges, Buildings, Dams, and Other Feats of Engineering (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0801894374).

- ↑ Francis D.K. Ching, A Visual Dictionary of Architecture (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2011. ISBN 978-0470648858).

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Robert Ousterhout, Master Builders of Byzantium (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2008, ISBN 978-1934536032).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Dorothea Baumann, Musical Acoustics in the Middle Ages Early Music 18(2) (May 1990): 199–212. Retrieved December 6, 2024.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Oleg Grabar, The Islamic Dome, Some Considerations Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 22(4) (1963): 191–198. Retrieved December 9, 2024.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Michael Fazio, Marian Moffett, and Lawrence Wodehouse, A World History of Architecture (London: Laurence King Publishing, 2013, ISBN 978-1780671116).

- ↑ Frank Sear, Roman Architecture (Routledge, 2020, ISBN 978-1138543737).

- ↑ James Stevens Curl, Classical Architecture: An Introduction to Its Vocabulary and Essentials, with a Select Glossary of Terms (W. W. Norton & Company, 2003, ISBN 978-0393731194).

- ↑ Mario Como, Statics of Historic Masonry Constructions (Springer, 2018, ISBN 978-3319854687).

- ↑ Jacob Burckhardt, The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987, ISBN 0226080498).

- ↑ D.H. Gye, Arches and Domes in Iranian Islamic Buildings: An Engineer's Perspective Iran 26 (1988): 129-144. Retrieved December 10, 2024.

- ↑ W.F. Chen and E.M. Lui (eds.), Handbook of Structural Engineering (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0849315695).

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Paula Fuentes González and Santiago Huerta, Islamic Domes of Crossed-arches: Origin, Geometry and Structural Behavior Baochun Chen and Jiangang Wei (eds.), ARCH'10 – 6th International Conference on Arch Bridges, October 11–13, 2010, Fuzhou, Fujian, China, 346–353. Retrieved December 10, 2024.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Donald Langmead and Christine Garnaut, Encyclopedia of Architectural and Engineering Feats (ABC-CLIO, 2001, ISBN 978-1576071120).

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 Colum Hourihane (ed.), The Grove Encyclopedia of Medieval Art and Architecture (Oxford University Press, 2012, ISBN 0195395360).

- ↑ Clarence Ward, Mediaeval Church Vaulting (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1915).

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Wolfgang Born, The Introduction of the Bulbous Dome into Gothic Architecture and Its Subsequent Development Speculum 19(2) (1944): 208–221. Retrieved December 10, 2024.

- ↑ Douglas Palmer, Unearthing the Past: The Great Discoveries of Archaeology from Around the World (Lyons Press, 2005, ISBN 978-1592287185).

- ↑ David P. Crandall, The Place of Stunted Ironwood Trees: A Year in the Lives of the Cattle-Herding Himba of Namibia (New York, NY: Continuum International Publishing Group, Inc., 2000, ISBN 978-0826412706).

- ↑ Oleg Grabar, The Islamic Dome, Some Considerations Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 22(4) (1963): 191–198. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Kathleen Kuiper, Culture of China (Britannica Educational Pub., 2010, ISBN 978-1615301409).

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Albert E. Dien, Six Dynasties Civilization (Yale University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0300074048).

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Karl Lehmann, "The Dome of Heaven", in W. Eugène Kleinbauer, (ed.), Modern Perspectives in Western Art History: An Anthology of Twentieth-Century Writings on the Visual Arts (University of Toronto Press, 1989, ISBN 978-0802067081) 227-270.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 32.6 32.7 Richard Krautheimer, Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture (Yale University Press, 1984, ISBN 978-0300052947).

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Lynne C. Lancaster, Concrete Vaulted Construction in Imperial Rome: Innovations in Context (Cambridge University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0521744362).

- ↑ Charles B. McClendon, The Origins of Medieval Architecture: Building in Europe, A.D 600–900 (Yale University Press, 2005, ISBN 978-0300106886).

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 Victoria Hammond and David Stephenson, Visions of Heaven: the Dome in European Architecture (Princeton Architectural Press, 2005, ISBN 978-1568985497).

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Godfrey Goodwin, A History of Ottoman Architecture (Thames & Hudson, 1971, ISBN 978-0500340400).

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 37.4 Patrick Nuttgens, The Story of Architecture (Phaidon Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0714836157).

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Stuart Tappin, The Structural Development of Masonry Domes in India Proceedings of the First International Congress on Construction History, Madrid, January 20-24, 2003. Retrieved December 12, 2024.

- ↑ Annarosa Cerutti Fusco and Marcello Villanni, Pietro da Cortona's domes between new experimentations and construction knowledge Proceedings of the First International Congress on Construction History, Madrid, January 20-24, 2003. Retrieved December 12, 2024.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 Rowland J. Mainstone, Developments in Structural Form (Routledge, 2001, ISBN 978-0750654517).

- ↑ Matthys Levy, and Mario Salvadori, Why buildings Fall Down: How Structures Fail (W. W. Norton & Company, 2002, ISBN 978-0393311525).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Burckhardt, Jacob. The Architecture of the Italian Renaissance. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987. ISBN 0226080498

- Chen, W.F., and E.M. Lui (eds.). Handbook of Structural Engineering. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0849315695

- Ching, Francis D.K. A Visual Dictionary of Architecture. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2011. ISBN 978-0470648858

- Como, Mario. Statics of Historic Masonry Constructions. Springer, 2018. ISBN 978-3319854687

- Crandall, David P. The Place of Stunted Ironwood Trees: A Year in the Lives of the Cattle-Herding Himba of Namibia. New York, NY: Continuum International Publishing Group, Inc., 2000. ISBN 978-0826412706

- Curl, James Stevens. Classical Architecture: An Introduction to Its Vocabulary and Essentials, with a Select Glossary of Terms. W. W. Norton & Company, 2003.ISBN 978-0393731194

- Denny, Mark. Super Structures: The Science of Bridges, Buildings, Dams, and Other Feats of Engineering. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0801894374

- Dien, Albert E. Six Dynasties Civilization. Yale University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0300074048

- Fazio, Michael, Marian Moffett, and Lawrence Wodehouse. A World History of Architecture. London: Laurence King Publishing, 2013. ISBN 978-1780671116

- Fleming, John, Hugh Honour, and Nikolaus Pevsner (eds.). The Penguin Dictionary of Architecture: Fourth .Penguin Books, 1991. ISBN 978-0140512410

- Goodwin, Godfrey. A History of Ottoman . Thames & Hudson, 1971. ISBN 978-0500340400

- Hammond, Victoria, and David Stephenson. Visions of Heaven: the Dome in European Architecture. Princeton Architectural Press, 2005. ISBN 978-1568985497

- Hourihane, Colum (ed.). The Grove Encyclopedia of Medieval Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press, 2012. ISBN 0195395360

- Kleinbauer, W. Eugène (ed.). Modern Perspectives in Western Art History: An Anthology of Twentieth-Century Writings on the Visual Arts. University of Toronto Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0802067081

- Krautheimer, Richard. Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture. Yale University Press, 1984. ISBN 978-0300052947

- Kuiper, Kathleen. Culture of China. Britannica Educational Pub., 2010. ISBN 978-1615301409

- Lancaster, Lynne C. Concrete Vaulted Construction in Imperial Rome: Innovations in Context. Cambridge University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0521744362

- Langmead, Donald, and Christine Garnaut. Encyclopedia of Architectural and Engineering Feats. ABC-CLIO, 2001. ISBN 978-1576071120

- Levy, Matthys, and Mario Salvadori. Why buildings Fall Down: How Structures Fail. W. W. Norton & Company, 2002. ISBN 978-0393311525

- Mainstone, Rowland J. Developments in Structural Form. Routledge, 2001. ISBN 978-0750654517

- McClendon, Charles B. The Origins of Medieval Architecture: Building in Europe, A.D 600–900. Yale University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0300106886

- Nuttgens, Patrick. The Story of Architecture. Phaidon Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0714836157

- Ousterhout, Robert. Master Builders of Byzantium. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, 2008. ISBN 978-1934536032

- Palmer, Douglas. Unearthing the Past: The Great Discoveries of Archaeology from Around the World. Lyons Press, 2005. ISBN 978-1592287185

- Peterson, Andrew. Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Routledge, 1996. ISBN 978-0415060844

- Sear, Frank. Roman Architecture. Routledge, 2020. ISBN 978-1138543737

- Smith, Earl Baldwin. The Dome: A Study in the History of Ideas. Princeton University Press, 1972. ISBN 978-0691003047

- Ward, Clarence. Mediaeval Church Vaulting. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1915. ASIN B00B2S2ECQ

- Wright, G.R.H. Building Technology, Volume 3: Construction. Brill, 2009. ISBN 9004177450

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.