Hagia Sophia

| Hagia Sophia Ayasofya (Turkish) | |

Hagia Sophia Church was built in 537 C.E., with minarets added in the fifteenthÔÇôsixteenth centuries when it became a mosque. | |

| Monument | |

|---|---|

| Type | * Chalcedonian church (c.┬á360 C.E.ÔÇô1054) |

| Location | Fatih, Istanbul, Turkey |

| Coordinates | |

| Construction | |

| Completed | 360 |

| Height | 55 meters (180 ft) |

| Width | 73 meters (240 ft) |

| Material | Ashlar, Roman brick |

| Design Team | |

| Designer | Isidore of Miletus Anthemius of Tralles |

| Website | |

Hagia Sophia (lit. 'Holy Wisdom'; Turkish: Ayasofya; Greek: ß╝ë╬│╬»╬▒ ╬ú╬┐¤ć╬»╬▒, romanized: Hag├şa Sof├şa; Latin: Sancta Sapientia), officially the Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque (Turkish: Ayasofya-i Kebir Cami-i ┼×erifi), is a mosque, a former church, and a major cultural and historical site in Istanbul, Turkey. It was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1985, as part of the Historic Areas of Istanbul.

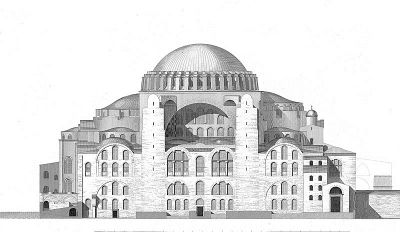

The current structure was built by the Byzantine emperor Justinian I as the Christian cathedral of Constantinople for the Byzantine Empire between 532 and 537, and was designed by the Greek geometers Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles. Upon completion became the world's largest interior space and among the first to employ a fully pendentive dome. It is considered the epitome of Byzantine architecture.

The site was an Eastern Orthodox church from 360 C.E. to 1204, when it was converted to a Catholic church following the Fourth Crusade. It was reclaimed in 1261 and remained Eastern Orthodox until the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453. It served as a mosque until 1935, when it became a museum.

In 2020, the site once again became a mosque. The decision to designate Hagia Sophia as a mosque was highly controversial. While the Hagia Sophia has now been rehallowed as a mosque, the place remains open for visitors outside of prayer times.

History

The history of Hagia Sophia includes not only destruction and rebuilding, but also changing its use from a Christian church for various denominations, to a mosque, and even spending decades as a museum. The current structure was built by the Byzantine emperor Justinian I as the Christian cathedral of Constantinople for the Byzantine Empire. It remained the world's largest cathedral for nearly a thousand years, until the Seville Cathedral was completed in 1520. Hagia Sophia has been described as "holding a unique position in the Christian world" and as an architectural and cultural icon of Byzantine and Eastern Orthodox civilization.[1] It was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1985, as part of the Historic Areas of Istanbul.

Church of Constantius II

The first church on the site was known as the Magna Ecclesia (Ancient Greek: ╬ť╬Á╬│╬Č╬╗╬Ě ß╝ś╬║╬║╬╗╬̤â╬»╬▒ )[2] because of its size compared to the sizes of the contemporary churches in the city. It was consecrated on February 15, 360, during the reign of the emperor Constantius II (r.ÔÇë306ÔÇô337), by the Arian bishop Eudoxius of Antioch.[3][4] It was built next to the area where the Great Palace was being developed. The nearby Hagia Irene ("Holy Peace") church was completed earlier and served as the cathedral until the Great Church was completed. According to the fifth-century ecclesiastical historian Socrates of Constantinople, the emperor Constantius had c.┬á346 "constructed the Great Church alongside that called Irene which because it was too small, the emperor's father [Constantine] had enlarged and beautified."[5][3]

The church is known to have had a timber roof, curtains, columns, and an entrance that faced west.[4] It likely had a narthex and is described as being shaped like a Roman circus.[5]

The building was accompanied by a baptistery and a skeuophylakion. A hypogeum, perhaps with an martyrium above it, was discovered before 1946, and the remnants of a brick wall with traces of marble revetment were identified in 2004.[4] The hypogeum was a tomb which may have been part of the fourth-century church or may have been from the pre-Constantinian city of Byzantium. The skeuophylakion is said by Palladius to have had a circular floor plan, and since some U-shaped basilicas in Rome were funerary churches with attached circular mausolea (the Mausoleum of Constantina and the Mausoleum of Helena), it is possible it originally had a funerary function, though by 405 its use had changed.[4]

A further remnant of the fourth century basilica may exist in a wall of alternating brick and stone banded masonry immediately to the west of the Justinianic church. The top part of the wall is constructed with bricks stamped with brick-stamps dating from the fifth century, but the lower part is of constructed with bricks typical of the fourth century. This wall was probably part of the propylaeum at the west front of both the Constantinian and Theodosian Great Churches.[4]

The Patriarch of Constantinople John Chrysostom came into a conflict with Empress Aelia Eudoxia, wife of the emperor Arcadius (r. 383-408), and was sent into exile in 404. During the subsequent riots, this first church was largely burnt down.[3] Palladius noted that the fourth-century skeuophylakion survived the fire. The fire may only have affected the main basilica, leaving the surrounding ancillary buildings intact.[4]

Church of Theodosius II

A second church on the site was ordered by Theodosius II (r. 402-450), who inaugurated it on October 10, 415.[6] The Notitia Urbis Constantinopolitanae, a fifth-century list of monuments, names Hagia Sophia as Magna Ecclesia (Great Church), while the former cathedral Hagia Irene is referred to as Ecclesia Antiqua (Old Church). At the time of Socrates of Constantinople around 440, "both churches [were] enclosed by a single wall and served by the same clergy."[5] Thus, the complex would have encompassed a large area including the future site of the Hospital of Samson. If the fire of 404 destroyed only the fourth-century main basilica church, then the fifth century Theodosian basilica could have been built surrounded by a complex constructed primarily during the fourth century.[4]

The area of the western entrance to the Justinianic Hagia Sophia revealed the western remains of its Theodosian predecessor, as well as some fragments of the Constantinian church. German archaeologist Alfons Maria Schneider began conducting archaeological excavations during the mid-1930s, publishing his final report in 1941. Excavations in the area that had once been the sixth-century atrium of the Justinianic church revealed the monumental western entrance and atrium, along with columns and sculptural fragments from both fourth- and fifth-century churches.[4] Further digging was abandoned for fear of harming the structural integrity of the Justinianic building, but parts of the excavation trenches remain uncovered, laying bare the foundations of the Theodosian building.

The basilica was built by architect Rufinus.[7] The church's main entrance, which may have had gilded doors, faced west, and there was an additional entrance to the east. There was a central pulpit and likely an upper gallery, possibly employed as a matroneum (women's section).[5] The exterior was decorated with elaborate carvings of rich Theodosian-era designs, fragments of which have survived, while the floor just inside the portico was embellished with polychrome mosaics. The surviving carved gable end from the center of the western fa├žade is decorated with a cross-roundel. Fragments of a frieze of reliefs with 12 lambs representing the 12 apostles also remain; unlike Justinian's sixth-century church, the Theodosian Hagia Sophia had both colorful floor mosaics and external decorative sculpture.[4]

At the western end, surviving stone fragments of the structure show there was vaulting. The propylaeum opened onto an atrium which lay in front of the basilica church itself. Preceding the propylaeum was a steep monumental staircase following the contours of the ground as it sloped away westwards in the direction of the Strategion, the Basilica, and the harbors of the Golden Horn. This arrangement would have resembled the steps outside the atrium of the Constantinian Old St Peter's Basilica in Rome. Near the staircase, there was a cistern, perhaps to supply a fountain in the atrium or for worshipers to wash with before entering.[4]

The fourth-century skeuophylakion was replaced in the fifth century by the present-day structure, a rotunda constructed of banded masonry in the lower two levels and of plain brick masonry in the third. Originally this rotunda, probably employed as a treasury for liturgical objects, had a second-floor internal gallery accessed by an external spiral staircase and two levels of niches for storage. A further row of windows with marble window frames on the third level remain bricked up. The gallery was supported on monumental consoles with carved acanthus designs, similar to those used on the late 5th-century Column of Leo. A large lintel of the skeuophylakion's western entrance ÔÇô bricked up during the Ottoman era ÔÇô was discovered inside the rotunda when it was archaeologically cleared to its foundations in 1979, during which time the brickwork was also repointed. The skeuophylakion was again restored in 2014 by the Vak─▒flar.[4]

A fire started during the tumult of the Nika Revolt, which had begun nearby in the Hippodrome of Constantinople, and the second Hagia Sophia was burnt to the ground on January 13ÔÇô14, 532. The court historian Procopius wrote:

And by way of shewing that it was not against the Emperor alone that they [the rioters] had taken up arms, but no less against God himself, unholy wretches that they were, they had the hardihood to fire the Church of the Christians, which the people of Byzantium call "Sophia", an epithet which they have most appropriately invented for God, by which they call His temple; and God permitted them to accomplish this impiety, foreseeing into what an object of beauty this shrine was destined to be transformed. So the whole church at that time lay a charred mass of ruins.[8]

Porphyry column; column capital; impost block

Church of Justinian I (current structure)

The current structure was built by the Byzantine emperor Justinian I as the Christian cathedral of Constantinople for the Byzantine Empire between 532 and 537, and was designed by the Greek geometers Isidore of Miletus and Anthemius of Tralles.[9] Upon completion it became the world's largest interior space and among the first to employ a fully pendentive dome. It is considered the epitome of Byzantine architecture.[10] The religious and spiritual center of the Eastern Orthodox Church for nearly one thousand years, the church was dedicated to the Holy Wisdom,[3] a reference to the second person of the Trinity, or Jesus Christ[11]

Originally the exterior of the church was covered with marble veneer, as indicated by remaining pieces of marble and surviving attachments for lost panels on the building's western face. The white marble cladding of much of the church, together with gilding of some parts, would have given Hagia Sophia a shimmering appearance quite different from the brick- and plaster-work of the modern period, and would have significantly increased its visibility from the sea.[4] The cathedral's interior surfaces were sheathed with polychrome marbles, green and white with purple porphyry, and gold mosaics. The exterior was clad in stucco that was tinted yellow and red during the nineteenth-century restorations by the Fossati architects.[12]

Columns and other marble elements were imported from throughout the Mediterranean, although the columns were once thought to be spoils from cities such as Rome and Ephesus.[13] Even though they were made specifically for Hagia Sophia, they vary in size.[14] Outside the church was an elaborate array of monuments around the bronze-plated Column of Justinian, topped by an equestrian statue of the emperor which dominated the Augustaeum, the open square outside the church which connected it with the Great Palace complex through the Chalke Gate. At the edge of the Augustaeum was the Milion and the Regia, the first stretch of Constantinople's main thoroughfare, the Mese. Also facing the Augustaeum were the enormous Constantinian thermae, the Baths of Zeuxippus, and the Justinianic civic basilica under which was the vast cistern known as the Basilica Cistern. On the opposite side of Hagia Sophia was the former cathedral, Hagia Irene.

Referring to the destruction of the Theodosian Hagia Sophia and comparing the new church with the old, Procopius lauded the Justinianic building, writing in De aedificiis:

The Emperor Justinian built not long afterwards a church so finely shaped, that if anyone had enquired of the Christians before the burning if it would be their wish that the church should be destroyed and one like this should take its place, shewing them some sort of model of the building we now see, it seems to me that they would have prayed that they might see their church destroyed forthwith, in order that the building might be converted into its present form.[8]

Justinian and Patriarch Menas inaugurated the new basilica on December 27, 537, 5 years and 10 months after construction started, with much pomp.[2]

Hagia Sophia was consecrated on December 27, 537, five years after construction had begun. The church was dedicated to the Wisdom of God, referring to the Logos (the second entity of the Trinity) or, alternatively, Christ as the Logos incarnate.[11]

Hagia Sophia was the seat of the Patriarchate of Constantinople and a principal setting for Byzantine imperial ceremonies, such as coronations. The basilica offered sanctuary from persecution to criminals.

Earthquakes in August 553 and on December 14, 557 caused cracks in the main dome and eastern semi-dome. During a subsequent earthquake on May 7, 558, the eastern semi-dome collapsed, destroying the ambon, altar, and ciborium. The collapse was due mainly to the excessive bearing load and to the enormous shear load of the dome, which was too flat. These caused the deformation of the piers which sustained the dome.[2]

Justinian ordered an immediate restoration. He entrusted it to Isidorus the Younger, nephew of Isidore of Miletus, who used lighter materials. The entire vault had to be taken down and rebuilt 20 Byzantine feet (6.25 meters (20.5 ft)) higher than before, giving the building its current interior height of 55.6 meters (182 ft). Moreover, Isidorus changed the dome type, erecting a ribbed dome with pendentives whose diameter was between 32.7 and 33.5 m.[2] Under Justinian's orders, eight Corinthian columns were disassembled from Baalbek, Lebanon and shipped to Constantinople around 560.[15] This reconstruction, which gave the church its present sixth-century form, was completed in 562.

In 726, the emperor Leo the Isaurian issued a series of edicts against the veneration of images, ordering the army to destroy all icons ÔÇô ushering in the period of Byzantine iconoclasm. At that time, all religious pictures and statues were removed from the Hagia Sophia.

The basilica then suffered damage, first in a great fire in 859, and again in an earthquake on January 8, 869 that caused the collapse of one of the half-domes. Emperor Basil I ordered repair of the tympanas, arches, and vaults.[16]

Early in the tenth century, the pagan ruler of the Kievan Rus' sent emissaries to his neighbors to learn about Judaism, Islam, and Roman and Orthodox Christianity. After visiting Hagia Sophia his emissaries reported back: "We were led into a place where they serve their God, and we did not know where we were, in heaven or on earth."[17]

After the great earthquake of October 25, 989, which collapsed the western dome arch, Emperor Basil II asked for the Armenian architect Trdat, creator of the Cathedral of Ani, to direct the repairs. He erected again and reinforced the fallen dome arch, and rebuilt the west side of the dome with 15 dome ribs.[2] The extent of the damage required six years of repair and reconstruction; the church was re-opened on May 13, 994. At the end of the reconstruction, the church's decorations were renovated, including the addition of four immense paintings of cherubs; a new depiction of Christ on the dome; a burial cloth of Christ shown on Fridays, and on the apse a new depiction of the Virgin Mary holding Jesus, between the apostles Peter and Paul. On the great side arches were painted the prophets and the teachers of the church.[18]

During the Latin occupation of Constantinople (1204ÔÇô1261), the church became a Latin Catholic cathedral. Upon the capture of Constantinople in 1261 by the Empire of Nicaea and the emperor Michael VIII Palaeologus, (r. 1261-1282), the church was in a dilapidated state. In 1317, emperor Andronicus II Palaeologus (r. 1282-1328) ordered four new buttresses to be built in the eastern and northern parts of the church.[2] New cracks developed in the dome after the earthquake of October 1344, and several parts of the building collapsed on May 19, 1346; repairs began in 1354.

Mosque (1453ÔÇô1935)

After the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453, Hagia Sophia was converted to a mosque by Mehmed the Conqueror who entered the city and performed the Friday prayer and khutbah (sermon) in Hagia Sophia, marking the official conversion of Hagia Sophia into a mosque.[19]

Upon its conversion, the bells, altar, iconostasis, ambo, and baptistery were removed, while iconography, such as the mosaic depictions of Jesus, Mary, Christian saints, and angels were removed or plastered over.[2] Islamic architectural additions included four minarets, a minbar and a mihrab. The Byzantine architecture of the Hagia Sophia served as inspiration for many other religious buildings including the Hagia Sophia in Thessaloniki, Panagia Ekatontapiliani, the ┼×ehzade Mosque, the S├╝leymaniye Mosque, the R├╝stem Pasha Mosque, and the K─▒l─▒├ž Ali Pasha Complex.

Before 1481, a small minaret was erected on the southwest corner of the building, above the stair tower. Mehmed's successor Bayezid II (r. 1481-1512) later built another minaret at the northeast corner. One of the minarets collapsed after the earthquake of 1509, and around the middle of the sixteenth century they were both replaced by two diagonally opposite minarets built at the east and west corners of the edifice.[2] In the sixteenth century, Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent (r. 1520-1566) brought two colossal candlesticks from his conquest of the Kingdom of Hungary and placed them on either side of the mihrab.

During the reign of Selim II (r. 1566-1574), the building started showing signs of fatigue and was extensively strengthened with the addition of structural supports to its exterior by Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan.[20] In addition to strengthening the historic Byzantine structure, Sinan built two additional large minarets at the western end of the building, the original sultan's lodge and the t├╝rbe (mausoleum) of Selim II to the southeast of the building in 1576ÔÇô1577 (AH 984). In order to do that, parts of the Patriarchate at the south corner of the building were pulled down the previous year. Moreover, the golden crescent was mounted on the top of the dome, and a respect zone 35 ar┼č─▒n (about 24┬ám) wide was imposed around the building, leading to the demolition of all houses within the perimeter. The t├╝rbe became the location of the tombs of 43 Ottoman princes. Murad III (r. 1574-1595) imported two large alabaster Hellenistic urns from Pergamon (Bergama) and placed them on two sides of the nave.[2]

In 1594 (AH 1004) Mimar (court architect) Davud A─ča built the t├╝rbe of Murad III, where the Sultan and his valide, Safiye Sultan were buried. The octagonal mausoleum of their son Mehmed III (r. 1595-1603) and his valide was built next to it in 1608 (AH 1017) by royal architect Dalgi├ž Mehmet A─Ła. His son Mustafa I (r. 1617-1618, 1622-1623) converted the baptistery into his t├╝rbe.[2]

In 1717, under the reign of Sultan Ahmed III (r. 1703-1730), the crumbling plaster of the interior was renovated, contributing indirectly to the preservation of many mosaics, which otherwise would have been destroyed by mosque workers. In fact, it was usual for the mosaic's tesseraeÔÇöbelieved to be talismansÔÇöto be sold to visitors.[2] Sultan Mahmud I ordered the restoration of the building in 1739 and added a medrese (a Koranic school, subsequently the library of the museum), an imaret (soup kitchen for distribution to the poor) and a library, and in 1740 he added a ┼×adirvan (fountain for ritual ablutions), thus transforming it into a k├╝lliye, or social complex. At the same time, a new sultan's lodge and a new mihrab were built inside.

Renovation of 1847ÔÇô1849

The nineteenth-century restoration of the Hagia Sophia was ordered by Sultan Abdulmejid I (r. 1823-1861) and completed between 1847 and 1849 by eight hundred workers under the supervision of the Swiss-Italian architect brothers Gaspare and Giuseppe Fossati. The brothers consolidated the dome with a restraining iron chain and strengthened the vaults, straightened the columns, and revised the decoration of the exterior and the interior of the building.[21] The mosaics in the upper gallery were exposed and cleaned, although many were recovered "for protection against further damage."[22]

Eight new gigantic circular-framed discs or medallions were hung from the cornice, on each of the four piers and at either side of the apse and the west doors. These were designed by the calligrapher Kazasker Mustafa Izzet Efendi (1801ÔÇô1877) and painted with the names of Allah, Muhammad, the Rashidun (the first four caliphs: Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman and Ali), and the two grandsons of Muhammad: Hasan and Husayn, the sons of Ali.

In 1850, the architects Fossati built a new maqsura or caliphal loge in Neo-Byzantine columns and an OttomanÔÇôRococo style marble grille connecting to the royal pavilion behind the mosque. The new maqsura was built at the extreme east end of the northern aisle, next to the north-eastern pier. The existing maqsura in the apse, near the mihrab, was demolished. A new entrance was constructed for the sultan. The Fossati brothers also renovated the minbar and mihrab.[21]

Outside the main building, the minarets were repaired and altered so that they were of equal height.[22] A clock building, the Muvakkithane, was built by the Fossatis for use by the muwaqqit (the mosque timekeeper), and a new madrasa (Islamic school) was constructed. The Kasr-─▒ H├╝mayun was also built under their direction An edition of lithographs from drawings made during the Fossatis' work on Hagia Sophia was published in London in 1852, entitled: Aya Sophia of Constantinople as Recently Restored by Order of H.M. The Sultan Abdulmedjid.[21]

- Gaspare Fossati's Hagia Sophia (lithographs by Louis Haghe)

Occupation of Istanbul (1918ÔÇô1923)

In the aftermath of the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I, Constantinople was occupied by British, French, Italian, and Greek forces. On January 19, 1919, the Greek Orthodox Christian military priest Eleftherios Noufrakis performed an unauthorized Divine Liturgy in the Hagia Sophia, the only such instance since the 1453 fall of Constantinople.[23]

The anti-occupation Sultanahmet demonstrations were held next to Hagia Sophia from March to May 1919. In Greece, the 500 drachma banknotes issued in 1923 featured Hagia Sophia.[24]

Museum (1935ÔÇô2020)

The complex remained a mosque until 1931, when it was closed to the public for four years. In 1935, the first Turkish President and founder of the Republic of Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Atat├╝rk, transformed the building into a museum. During the Second World War, the minarets of the museum housed MG 08 machine guns.[25] The carpet and the layer of mortar underneath were removed and marble floor decorations such as the omphalion appeared for the first time since the Fossatis' restoration.[26]

Due to neglect, the condition of the structure continued to deteriorate, prompting the World Monuments Fund (WMF) to include the Hagia Sophia in their 1996 and 1998 Watch Lists. During this time period, the building's copper roof had cracked, causing water to leak down over the fragile frescoes and mosaics. Moisture entered from below as well. Rising ground water increased the level of humidity within the monument, creating an unstable environment for stone and paint. The WMF secured a series of grants from 1997 to 2002 for the restoration of the dome. The first stage of work involved the structural stabilization and repair of the cracked roof, which was undertaken with the participation of the Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism. The second phase, the preservation of the dome's interior, afforded the opportunity to employ and train young Turkish conservators in the care of mosaics. By 2006, the WMF project was complete, though many areas of Hagia Sophia continue to require significant stability improvement, restoration, and conservation.[27]

From the early 2010s, several campaigns and government high officials, notably Turkey's deputy prime minister B├╝lent Ar─▒n├ž, demanded the Hagia Sophia be converted back into a mosque.[28]

On July 1, 2016, Muslim prayers were held again in the Hagia Sophia for the first time in 85┬áyears.[29] In October 2016, Turkey's Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet) appointed, for the first time in 81 years, a designated imam, ├ľnder Soy, to the Hagia Sophia mosque (Ayasofya Camii H├╝nkar Kasr─▒), located at the H├╝nkar Kasr─▒, a pavilion for the sultans' private ablutions. Since then, the adhan has been regularly called out from the Hagia Sophia's all four minarets five times a day.[30]

Reversion to mosque (2018ÔÇôpresent)

In July 2020, the Council of State annulled the 1934 decision to establish the museum, and the Hagia Sophia was reclassified as a mosque. The decree was ruled to be unlawful under both Ottoman and Turkish law as Hagia Sophia's waqf, endowed by Sultan Mehmed, had designated the site a mosque; proponents of the decision argued the Hagia Sophia was the personal property of the sultan.[31]

When President Erdo─čan announced that the first Muslim prayers would be held inside the building on July 24, he added that "like all our mosques, the doors of Hagia Sophia will be wide open to locals and foreigners, Muslims and non-Muslims." Presidential spokesman ─░brahim Kal─▒n said that the icons and mosaics of the building would be preserved, and that "in regards to the arguments of secularism, religious tolerance and coexistence, there are more than four hundred churches and synagogues open in Turkey today."[32]

This decision to designate Hagia Sophia as a mosque was highly controversial. It resulted in divided opinions and drew condemnation from various organizations including UNESCO,[33] the World Council of Churches,[34] and the International Association of Byzantine Studies,[35] as well as numerous international leaders.

In April 2022, the Hagia Sophia held its first Ramadan tarawih prayer in 88 years.[36] Hagia Sophia remains open for visitors outside of prayer times.

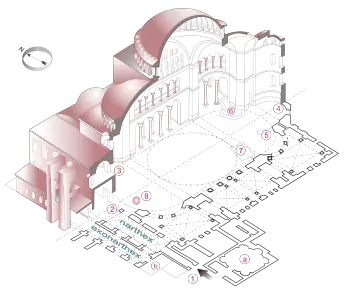

Architecture

Hagia Sophia is one of the greatest surviving examples of Byzantine architecture.[10] Its interior is decorated with mosaics, marble pillars, and coverings of great artistic value. Justinian's basilica was at once the culminating architectural achievement of late antiquity and the first masterpiece of Byzantine architecture. Its influence, both architecturally and liturgically, was widespread and enduring in the Eastern Christianity, Western Christianity, and Islam alike.[37] Hagia Sophia was the greatest cathedral ever built up to that time, and it was to remain the largest cathedral for 1,000 years until the completion of the cathedral in Seville in Spain.[38]

Hagia Sophia uses masonry construction, with brick and mortar joints that are 1.5 times the width of the bricks. The mortar joints are composed of a combination of sand and minute ceramic pieces distributed evenly throughout the mortar joints. This combination of sand and potsherds was often used in Roman concrete, a predecessor to modern concrete. Each of the four sides of the great square Hagia Sophia is approximately 31 m long.[39]

At the western entrance and eastern liturgical side, there are arched openings extended by half domes of identical diameter to the central dome, carried on smaller semi-domed exedrae, a hierarchy of dome-headed elements built up to create a vast oblong interior crowned by the central dome, with a clear span of 76.2 meters (250 ft).[10]

The vast interior has a complex structure. The nave is covered by a central dome which at its maximum is 55.6 m (182 ft 5 in) from floor level and rests on an arcade of 40 arched windows. Repairs to its structure have left the dome somewhat elliptical, with the diameter varying between 31.24 and 30.86 m (102 ft 6 in and 101 ft 3 in).[40]

Floor

The stone floor of Hagia Sophia dates from the sixth century. After the first collapse of the vault, the broken dome was left in situ on the original Justinianic floor and a new floor was laid above the rubble when the dome was rebuilt in 558. From the installation of this second Justinianic floor, the floor became part of the liturgy, with significant locations and spaces demarcated in various ways using different-colored stones and marbles.[4]

The floor is predominantly made from Proconnesian marble, quarried on Proconnesus (Marmara Island) in the Propontis (Sea of Marmara). This white marble was used in the monuments of Constantinople. Other parts of the floor, like the Thessalian verd antique "marble," were quarried in Thessaly in Roman Greece.

The floor was praised by numerous authors and repeatedly compared to a sea. The Justinianic poet Paul the Silentiary likened the ambo and the solea connecting it to the sanctuary with an island in a sea, with the sanctuary itself a harbor. The ninth-century Narratio writes of it as "like the sea or the flowing waters of a river."[41] Michael the Deacon in the twelfth century also described the floor as a sea in which the ambo and other liturgical furniture stood as islands. During the fifteenth-century conquest of Constantinople, the Ottoman caliph Mehmed is said to have ascended to the dome and the galleries in order to admire the floor, which according to Tursun Beg resembled "a sea in a storm" or a "petrified sea."[41]

Upper gallery

The upper gallery, or matroneum, is horseshoe-shaped; it encloses the nave on three sides and is interrupted by the apse. Several mosaics are preserved in the upper gallery, an area traditionally reserved for the Empress and her court. The best-preserved mosaics are located in the southern part of the gallery.

The northern first floor gallery contains Scandinavian Runic inscriptions believed to have been left by members of the Varangian Guard.[42]

Dome

The dome of Hagia Sophia has spurred particular interest for many art historians, architects, and engineers because of the innovative way the original architects envisioned it. The dome is carried on four spherical triangular pendentives, making the Hagia Sophia one of the first large-scale uses of this element. The pendentives are the corners of the square base of the dome, and they curve upwards into the dome to support it, thus restraining the lateral forces of the dome and allowing its weight to flow downwards.[9] The main dome of the Hagia Sophia was the largest pendentive dome in the world until the completion of St Peter's Basilica, and it has a much lower height than any other dome of such a large diameter.

The great dome at the Hagia Sophia is 32.6 meters (one hundred and seven feet) in diameter and is only 0.61 meters (two feet) thick: "it is unlikely that the vaulting-shell is anywhere more than one normal brick in thickness."[5] The weight of the dome remained a problem for most of the building's existence. The original cupola collapsed entirely after the earthquake of 558; in 563 a new dome was built by Isidore the Younger, a nephew of Isidore of Miletus. Unlike the original, this included 40 ribs and was raised 6.1 meters (20 feet), in order to lower the lateral forces on the church walls. A larger section of the second dome collapsed as well, over two episodes, so that as of 2021, only two sections of the present dome, the north and south sides, are from the 562 reconstructions. Of the whole dome's 40 ribs, the surviving north section contains eight ribs, while the south section includes six ribs.[5]

Although this design stabilizes the dome and the surrounding walls and arches, the actual construction of the walls of Hagia Sophia weakened the overall structure. The bricklayers used more mortar than brick, which is more effective if the mortar was allowed to settle, as the building would have been more flexible; however, the builders did not allow the mortar to cure before they began the next layer. When the dome was erected, its weight caused the walls to lean outward because of the wet mortar underneath. When Isidore the Younger rebuilt the fallen cupola, he had first to build up the interior of the walls to make them vertical again. Additionally, the architect raised the height of the rebuilt dome by approximately Template:Convert/metres so that the lateral forces would not be as strong and its weight would be transmitted more effectively down into the walls. Moreover, he shaped the new cupola like a scalloped shell or the inside of an umbrella, with ribs that extend from the top down to the base. These ribs allow the weight of the dome to flow between the windows, down the pendentives, and ultimately to the foundation.[5]

Hagia Sophia is famous for the light that reflects everywhere in the interior of the nave, giving the dome the appearance of hovering above. This effect was achieved by inserting forty windows around the base of the original structure. Moreover, the insertion of the windows in the dome structure reduced its weight.[5]

Buttresses

Numerous buttresses have been added throughout the centuries. The flying buttresses to the west of the building were built during the Byzantine era. This shows that the Romans had prior knowledge of flying buttresses, which can also be seen at in Greece, at the Rotunda of Galerius in Thessaloniki, at the monastery of Hosios Loukas in Boeotia, and in Italy at the octagonal basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna.[5] Other buttresses were constructed during the Ottoman times under the guidance of the architect Sinan.

Minarets

The minarets were an Ottoman addition and not part of the original church's Byzantine design. They were built for notification of invitations for prayers (adhan) and announcements. Mehmed had built a wooden minaret over one of the half domes soon after Hagia Sophia's conversion from a cathedral to a mosque.[43] This minaret does not exist today. One of the minarets (at southeast) was built from red brick and can be dated back from the reign of Mehmed or his successor Beyazıd II. The other three were built from white limestone and sandstone, of which the slender northeast column was erected by Bayezid II and the two identical, larger minarets to the west were erected by Selim II and designed by the famous Ottoman architect Mimar Sinan. Both are 60 meters (200 ft) in height, and their thick and massive patterns complete Hagia Sophia's main structure. Many ornaments and details were added to these minarets on repairs during the fifteenth, sixteenth, and nineteenth centuries, which reflect each period's characteristics and ideals.

Notable elements and decorations

Originally, under Justinian's reign, the interior decorations consisted of abstract designs on marble slabs on the walls and floors as well as mosaics on the curving vaults. Of these mosaics, the two archangels Gabriel and Michael are still visible in the spandrels (corners) of the bema. The spandrels of the gallery are faced in inlaid thin slabs (opus sectile), showing patterns and figures of flowers and birds in precisely cut pieces of white marble set against a background of black marble. In later stages, figurative mosaics were added, which were destroyed during the iconoclastic controversy (726ÔÇô843). Present mosaics are from the post-iconoclastic period.

Apart from the mosaics, many figurative decorations were added during the second half of the ninth century: an image of Christ in the central dome; Eastern Orthodox saints, prophets, and Church Fathers in the tympana below; historical figures connected with this church, such as Patriarch Ignatius; and some scenes from the Gospels in the galleries. Basil II let artists paint a giant six-winged seraph on each of the four pendentives. The Ottomans covered their faces with golden stars,[18] although one has been restored to its original state.

Loggia of the Empress

The loggia of the empress is located in the center of the gallery of the Hagia Sophia, above the Imperial Gate and directly opposite the apse. From this matroneum (women's gallery), the empress and the court-ladies would watch the proceedings down below. A green stone disc of verd antique marks the spot where the throne of the empress stood.

Lustration urns

Two huge marble lustration (ritual purification) urns were brought from Pergamon during the reign of Sultan Murad III. They are from the Hellenistic period and carved from single blocks of marble.[2]

Marble Door

The Marble Door inside the Hagia Sophia is located in the southern upper enclosure or gallery. It was used by the participants in synods, who entered and left the meeting chamber through this door. The door opens into a space that was used as a venue for solemn meetings and important resolutions of patriarchate officials.[44]

Beautiful Door

The Beautiful Door is the oldest architectural element found in the Hagia Sophia, dating back to the second century B.C.E. The decorations are of reliefs of geometric shapes as well as plants that are believed to have come from a pagan temple in Tarsus in Cilicia, part of the Cibyrrhaeot Theme in modern-day Mersin Province in south-eastern Turkey. It was incorporated into the building by Emperor Theophilos in 838, and placed in the south exit in the inner narthex.[44]

Imperial Door

The Imperial Gate, or Imperial Door, was the main entrance between the exo- and esonarthex, and it was originally exclusively used by the emperor and his personal bodyguard and retinue.[45] It is the largest door in the Hagia Sophia and has been dated to the sixth century. It is about 7 meters tall and made of wood, with wings covered in bronze plates.[44]

A long ramp from the northern part of the outer narthex leads up to the upper gallery.[46]

Wishing column

At the northwest of the building, there is a column with a hole in the middle covered by bronze plates. This column goes by different names; the "perspiring" or "sweating column," the "crying column," or the "wishing column." Legend states that it has been moist since the appearance of Gregory the Wonderworker near the column in 1200. It is believed that touching the moisture cures many illnesses.[47]

Mosaics

The first mosaics which adorned the church were completed during the reign of Justin II.[48] Many of the non-figurative mosaics in the church come from this period. Most of the mosaics, however, were created in the tenth and twelfth centuries, following the periods of Byzantine Iconoclasm.

During the Sack of Constantinople in 1204, the Latin Crusaders vandalized valuable items in every important Byzantine structure of the city, including the golden mosaics of the Hagia Sophia. Many of these items were shipped to Venice.

Following the building's conversion into a mosque in 1453, many of its mosaics were covered with plaster, due to Islam's ban on representational imagery. This process was not completed at once, and reports exist from the seventeenth century in which travelers note that they could still see Christian images in the former church.

Nineteenth-century restoration

In 1847ÔÇô1849, the building was restored by two Swiss-Italian Fossati brothers, Gaspare and Giuseppe, and Sultan Abdulmejid I allowed them to also document any mosaics they might discover during this process, which were later archived in Swiss libraries. This work did not include repairing the mosaics, and after recording the details about an image, the Fossatis painted over it again. The Fossatis restored the mosaics of the two hexapteryga (singular Greek: ß╝Ĺ╬ż╬▒¤Ç¤ä╬ş¤ü¤ů╬│╬┐╬Ż, pr. hexapterygon, six-winged angel; it is uncertain whether they are seraphim or cherubim) located on the two east pendentives, and covered their faces again before the end of the restoration. The other two mosaics, placed on the west pendentives, are copies in paint created by the Fossatis since they could find no surviving remains of them. As in this case, the architects reproduced in paint damaged decorative mosaic patterns, sometimes redesigning them in the process.

The Fossati records are the primary sources about a number of mosaic images now believed to have been completely or partially destroyed in the 1894 Istanbul earthquake. These include a mosaic over a now-unidentified Door of the Poor, a large image of a jewel-encrusted cross, and many images of angels, saints, patriarchs, and church fathers. The Fossatis' drawings of the Hagia Sophia mosaics are today kept in the Archive of the Canton of Ticino.

Apse mosaic of the Virgin Mary and Christ the Child.

Mosaic in the northern tympanum depicting Saint John Chrysostom

Twentieth-century restoration

Many mosaics were uncovered in the 1930s by a team from the Byzantine Institute of America led by Thomas Whittemore. The team chose to let a number of simple cross images remain covered by plaster but uncovered all major mosaics found.

Because of its long history as both a church and a mosque, a particular challenge arises in the restoration process. Christian iconographic mosaics can be uncovered, but often at the expense of important and historic Islamic art. Restorers have attempted to maintain a balance between both Christian and Islamic cultures.

Imperial Gate mosaic

The Imperial Gate mosaic is located in the tympanum above that gate, which was used only by the emperors when entering the church. Based on style analysis, it has been dated to the late ninth or early tenth century. The emperor with a nimbus or halo is bowing down before Christ Pantocrator, seated on a jeweled throne, giving his blessing and holding in his left hand an open book. The text on the book reads: "Peace be with you" (John 20:19, John 20:26) and "I am the light of the world" (John 8:12). On each side of Christ's shoulders is a circular medallion with busts: on his left the Archangel Gabriel, holding a staff, on his right his mother Mary.[49]

Southwestern entrance mosaic

The southwestern entrance mosaic, situated in the tympanum of the southwestern entrance, dates from the reign of Basil II. It was rediscovered during the restorations of 1849 by the Fossatis. The Virgin sits on a throne without a back, her feet resting on a pedestal, embellished with precious stones. The Christ Child sits on her lap, giving his blessing and holding a scroll in his left hand. On her left side stands emperor Constantine in ceremonial attire, presenting a model of the city to Mary. The inscription next to him says: "Great emperor Constantine of the Saints." On her right side stands emperor Justinian I, offering a model of the Hagia Sophia. The medallions on both sides of the Virgin's head carry the nomina sacra MP and ╬ś╬ą, abbreviations of the Ancient Greek: ╬ť╬«¤ä╬̤ü ¤ä╬┐¤ů ╬ś╬Á╬┐ß┐Ž .[50] The composition of the figure of the Virgin enthroned was probably copied from the mosaic inside the semi-dome of the apse inside the liturgical space.[51]

Apse mosaics

The mosaic in the semi-dome above the apse at the east end shows Mary, mother of Jesus holding the Christ Child and seated on a jeweled thokos backless throne. Since its rediscovery after a period of concealment in the Ottoman era, it "has become one of the foremost monuments of Byzantium."[51] The infant Jesus's garment is depicted with golden tesserae.

It is not known when this mosaic was installed. The work is generally believed to date from after the end of Byzantine Iconoclasm and usually dated to the patriarchate of Photius I (r. 858-867, 877-886) and the time of the emperors Michael III (r. 842-867) and Basil I (r. 867-886). However, other scholars have favored earlier or later dates for the present mosaic or its composition.[51]

The mosaic of the Virgin and Child was rediscovered during the restorations of the Fossati brothers in 1847ÔÇô1848 and revealed by the restoration of Thomas Whittemore in 1935ÔÇô1939.[51]

Emperor Alexander mosaic

The Emperor Alexander mosaic is located on the second floor in a dark corner of the ceiling. It depicts the emperor Alexander in full regalia, holding a scroll in his right hand and a globus cruciger in his left. A drawing by the Fossatis showed that the mosaic survived until 1849 and that Thomas Whittemore assumed that it had been destroyed in the earthquake of 1894. Unlike most of the other mosaics in Hagia Sophia, which had been covered over by ordinary plaster, the Alexander mosaic was simply painted over and reflected the surrounding mosaic patterns and thus was well hidden.[52]

Empress Zoe mosaic

The Empress Zoe mosaic on the eastern wall of the southern gallery dates from the eleventh century. Christ Pantocrator, clad in the dark blue robe (as is the custom in Byzantine art), is seated in the middle against a golden background, giving his blessing with the right hand and holding the Bible in his left hand. On either side of his head are the nomina sacra IC and XC, meaning I─ôsous Christos. He is flanked by Constantine IX Monomachus and Empress Zoe, both in ceremonial costumes. He is offering a purse, as a symbol of donation, he made to the church, while she is holding a scroll, symbol of the donations she made. The inscription over the head of the emperor says: "Constantine, pious emperor in Christ the God, king of the Romans, Monomachus." [53]

Comnenus mosaic

The Comnenus mosaic, also located on the eastern wall of the southern gallery, dates from 1122. The Virgin Mary is standing in the middle, depicted, as usual in Byzantine art, in a dark blue gown. She holds the Christ Child on her lap. He gives his blessing with his right hand while holding a scroll in his left hand. On her right side stands emperor John II Comnenus, represented in a garb embellished with precious stones. He holds a purse, symbol of an imperial donation to the church. His wife, the empress Irene of Hungary stands on the left side of the Virgin, wearing ceremonial garments and offering a document. Their eldest son Alexius Comnenus is represented on an adjacent pilaster. He is shown as a beardless youth, probably representing his appearance at his coronation aged seventeen. In this panel, one can already see a difference with the Empress Zoe mosaic that is one century older. There is a more realistic expression in the portraits instead of an idealized representation.[54]

De├źsis mosaic

The De├źsis mosaic (╬ö╬ş╬̤â╬╣¤é, "Entreaty") probably dates from 1261. It was commissioned to mark the end of 57 years of Latin Catholic use and the return to the Eastern Orthodox faith. It is the third panel situated in the imperial enclosure of the upper galleries. It is widely considered the finest in Hagia Sophia, because of the softness of the features, the humane expressions, and the tones of the mosaic. The style is close to that of the Italian painters of the late thirteenth or early fourteenth century, such as Duccio. In this panel the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist (Ioannes Prodromos), both shown in three-quarters profile, are imploring the intercession of Christ Pantocrator for humanity on Judgment Day. The bottom part of this mosaic is badly deteriorated.[55] This mosaic is considered as the beginning of a renaissance in Byzantine pictorial art.[56]

Northern tympanum mosaics

The northern tympanum mosaics feature various saints. They have been able to survive due to their high and inaccessible location. They depict Patriarchs of Constantinople John Chrysostom and Ignatios of Constantinople standing, clothed in white robes with crosses, and holding richly jewelled Bibles. The figures of each patriarch, revered as saints, are identifiable by labels in Greek. The other mosaics in the other tympana have not survived probably due to the frequent earthquakes, as opposed to any deliberate destruction by the Ottoman conquerors.[57]

Dome mosaic

The dome was decorated with four non-identical figures of the six-winged angels which protect the Throne of God; it is uncertain whether they are seraphim or cherubim. The mosaics survive in the eastern part of the dome, but since the ones on the western side were damaged during the Byzantine period, they have been renewed as frescoes. During the Ottoman period each angel's face was covered with metallic lids in the shape of stars, but these were removed to reveal the faces during renovations in 2009.[44]

Works influenced by the Hagia Sophia

Many buildings have been modeled on the Hagia Sophia's core structure of a large central dome resting on pendentives and buttressed by two semi-domes.

Byzantine churches influenced by the Hagia Sophia include the Hagia Sophia in Thessaloniki, and the Hagia Irene. The latter was remodeled to have a dome similar to the Hagia Sophia's during the reign of Justinian.

Several mosques commissioned by the Ottoman dynasty have plans based on the Hagia Sophia, including the S├╝leymaniye Mosque and the Bayezid II Mosque.[58] Ottoman architects preferred to surround the central dome with four semi-domes rather than two. There are four semi-domes on the Sultan Ahmed Mosque, the Fatih Mosque,[37] and the New Mosque (Istanbul). As with the original plan of the Hagia Sophia, these mosques are entered through colonnaded courtyards. However, the courtyard of the Hagia Sophia no longer exists.

As with Ottoman mosques, several churches based on the Hagia Sophia include four semi-domes rather than two, such as the Church of Saint Sava in Belgrade. The Catedral Metropolitana Ortodoxa in São Paulo and the Église du Saint-Esprit (Paris) both replace the two large tympanums beneath the main dome with two shallow semi-domes. The Église du Saint-Esprit is two thirds the size of the Hagia Sophia.

Several churches combine elements of the Hagia Sophia with a Latin cross plan. For instance, the transept of the Cathedral Basilica of Saint Louis (St. Louis) is formed by two semi-domes surrounding the main dome. The church's column capitals and mosaics also emulate the style of the Hagia Sophia. Other examples include the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, Sofia, St Sophia's Cathedral, London, Saint Clement Catholic Church, Chicago, and the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception.

Synagogues based on the Hagia Sophia include the Congregation Emanu-El (San Francisco),[59] Great Synagogue of Florence, and Hurva Synagogue.

Gallery

Interior of the Hagia Sophia by John Singer Sargent, 1891

Photograph by S├ębah & Joaillier, c.┬á1900ÔÇô1910

Detail of relief on the Marble Door.

Notes

- ÔćĹ John Meyendorff, The Byzantine Legacy in the Orthodox Church (Yonkers: St Vladimir's Seminary Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0913836903).

- ÔćĹ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 Wolfgang M├╝ller-Wiener, Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls (Wasmuth, 1977, ISBN 978-3803010223).

- ÔćĹ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Raymond Janin, Les Eglises Et Les Monasteres: La Geographie Ecclesiastique de L'Empire Byzantin (Peeters, 1969, ISBN 978-9042931206).

- ÔćĹ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 Ken Dark and Jan Kostenec, Hagia Sophia in Context: An Archaeological Re-examination of the Cathedral of Byzantine Constantinople (Oxbow Books, 2023, ISBN 978-1789259872).

- ÔćĹ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 Rowland J. Mainstone, Hagia Sophia: Architecture, Structure and Liturgy of Justinian's Great Church (Thames & Hudson, 1988, ISBN 978-0500340981).

- ÔćĹ Peter Crawford, Roman Emperor Zeno: The Perils of Power Politics in Fifth-Century Constantinople (Pen and Sword History, 2019, ISBN 978-1473859241).

- ÔćĹ Exterior, Walls and Architectural Elements JSTOR. Retrieved July 11, 2024.

- ÔćĹ 8.0 8.1 Procopius, The Buildings of Procopius Retrieved July 11, 2024.

- ÔćĹ 9.0 9.1 Fred S. Kleiner, Gardner's Art Through the Ages: A Global History, Volume I (Cengage Learning, 2019, ISBN 978-1337696593).

- ÔćĹ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Michael Fazio, Marian Moffett, and Lawrence Wodehouse, Buildings Across Time: An Introduction to World Architecture (McGraw Hill, 2022, ISBN 978-1265219499).

- ÔćĹ 11.0 11.1 Florin Curta and Andrew Holt (eds.), Great Events in Religion: An Encyclopedia of Pivotal Events in Religious History (ABC-CLIO, 2016, ISBN 978-1610695657).

- ÔćĹ Natalia B. Teteriatnikov, Mosaics of Hagia Sophia, Istanbul: The Fossati restoration and the work of the Byzantine Institute (Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1998, ISBN 978-0884022640).

- ÔćĹ Richard Krautheimer, Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture (Yale University Press, 1984, ISBN 978-0300052947).

- ÔćĹ Cyril Mango, Byzantine Architecture (Electa / Rizzoli, 1985, ISBN 978-0847806157).

- ÔćĹ Baalbek keeps its secrets Stone World, September 1, 2002. Retrieved July 11, 2024.

- ÔćĹ Natalia Teteriatnikov, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople: Religious images and their functional context after iconoclasm Zograf 30 (2004-2005): 9ÔÇô19. Retrieved July 11, 2024.

- ÔćĹ Witold Rybczynski, The Story of Architecture (Yale University Press, 2022, ISBN 978-0300246063).

- ÔćĹ 18.0 18.1 Ernest Mamboury, The Tourists' Istanbul (Cituri Biraderler Basimevi, 1953).

- ÔćĹ (2016-10-27) Contested Spaces, Common Ground: Space and Power Structures in Contemporary Multireligious Societies (in en). BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-32580-7.┬á

- ÔćĹ Murat Sofuoglu, How the Ottoman architect Sinan helped Hagia Sophia survive for centuries TRT World. Retrieved July 12, 2024.

- ÔćĹ 21.0 21.1 21.2 The Fossati brothers Turkish Cultural Foundation. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ÔćĹ 22.0 22.1 Jonathan M. Bloom and Sheila S. Blair (eds.), The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture (Oxford University Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0195309911).

- ÔćĹ Anthony E. Stivaktakis, The Last Divine Liturgy in Hagia Sophia of 1919 Mystagogy Resource Center, June 9, 2015. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ÔćĹ 500 Drachmai Numista. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ÔćĹ September 1941 (Ayasofya Minaret) NTV. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ÔćĹ Mustafa Sahin (ed.), 11th International Colloquium on Ancient Mosaics, October 16th-20th, 2009, Bursa, Turkey: Mosaics of Turkey and Parallel Developments in the Rest of the Ancient and Medieval World (Ege Yayinlari, 2012, ISBN 978-6055607814).

- ÔćĹ Hagia Sophia World Monuments Fund. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ÔćĹ Michael Trimmer, Turkey: Pressure mounts for Hagia Sophia to be converted into mosque Christianity Today (December 13, 2013). Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ÔćĹ First call to prayer inside Istanbul's Hagia Sophia in 85 years H├╝rriyet Daily News (July 3, 2016). Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ÔćĹ Sertan Sanderson, Hagia Sophia imam: part of Erdogan's Islamization drive? Deutsche Welle (November 7, 2016). Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ÔćĹ Turkish court rules 1934 conversion of Hagia Sophia into museum illegal TRT World. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ÔćĹ Havva Kara Aydin, Turkish spokesman: Hagia Sophia icons to be preserved Anadolu Agency (July 11, 2020). Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ÔćĹ UNESCO statement on Hagia Sophia, Istanbul UNESCO, July 10, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ÔćĹ Hagia Sophia: World Council of Churches appeals to Turkey on mosque decision BBC (July 11, 2020). Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ÔćĹ John F. Haldon, Letter Regarding the Status of Hagia Sophia International Association of Byzantine Studies, June 25, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ÔćĹ Zeynep Rakipoglu, Turkiye's Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque to hold 1st tarawih prayer in 88 years Anadolu Agency, March 31, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ÔćĹ 37.0 37.1 Saqer Sqour, Influence of Hagia Sophia on the Construction of Dome in Mosque Architecture 8th International Conference on Latest Trends in Engineering and Technology (ICLTET'2016), May 5-6 2016 Dubai (UAE). Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ÔćĹ J. Gordon Melton and Martin Baumann (eds.), Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices (ABC-CLIO, 2002, ISBN 978-1576072233).

- ÔćĹ Nadine Schibille, Hagia Sophia and the Byzantine Aesthetic Experience (Routledge, 2020, ISBN 978-0367600358).

- ÔćĹ Jan Plach├Ż, Josef Mus├şlek, Lubo┼í Podolka, and Monika Karkov├í, Disorders of the Building and its Remediation - Hagia Sophia, Turkey the Most the Byzantine Building Procedia Engineering 161 (2016): 2259ÔÇô2264. Retrieved July 15, 2024.

- ÔćĹ 41.0 41.1 Fabio Barry, Walking on Water: Cosmic Floors in Antiquity and the Middle Ages The Art Bulletin 89(4) (2007): 627ÔÇô656. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ÔćĹ Elena A. Mel'nikova, A New Runic Inscription from Hagia Sophia Cathedral in Istanbul Institute of World History, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow Oslo, Uppsala, 2016. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ÔćĹ William Emerson and Robert L. van Nice, Hagia Sophia and the First Minaret Erected after the Conquest of Constantinople American Journal of Archaeology 54(1) (January-March, 1950): 28-40. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ÔćĹ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 The Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque Hagia Sophia Museum. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ÔćĹ Emilie M. van Opstall, Sacred Thresholds: The Door to the Sanctuary in Late Antiquity (Brill, 2018, ISBN 9004368590).

- ÔćĹ Imperial Gate Of Hagia Sophia Hagia Sophia Imperial Gate. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ÔćĹ Hagia Sophia Wishing Column Atlas Obscura. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ÔćĹ Nicholas N. Patricios, The Sacred Architecture of Byzantium: Art, Liturgy and Symbolism in Early Christian Churches (I.B.Tauris, 2013, ISBN 978-1780762913).

- ÔćĹ Imperial Door Mosaic Hagia Sophia. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ÔćĹ Southwestern Vestibule Hagia Sophia. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ÔćĹ 51.0 51.1 51.2 51.3 Zaza Skhirtladze, The Image of the Virgin on the Sinai Hexaptych and the Apse Mosaic of Hagia Sophia, Constantinople Dumbarton Oaks Papers 68 (2014): 369ÔÇô386. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ÔćĹ Emperor Alexander Hagia Sophia. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ÔćĹ Empress Zoe Hagia Sophia. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ÔćĹ Comnenus Hagia Sophia. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ÔćĹ Ken Parry, The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010, ISBN 978-1444333619).

- ÔćĹ Deesis Hagia Sophia. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ÔćĹ North Tympanum Hagia Sophia. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ÔćĹ Elisabeth Piltz, Hagia Sophia and Ottoman architecture Byzantinoslavica - Revue internationale des ├ëtudes Byzantines 1-2 (2014): 293ÔÇô309. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ÔćĹ W. Eugene Kleinbauer, Hagia Sophia, 1850-1950: Holy Wisdom Modern Monument (review) The Catholic Historical Review 93(2) (April 2007): 367ÔÇô370. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bloom, Jonathan M., and Sheila S. Blair (eds.). The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0195309911

- Crawford, Peter. Roman Emperor Zeno: The Perils of Power Politics in Fifth-Century Constantinople. Pen and Sword History, 2019. ISBN 978-1473859241

- Curta, Florin, and Andrew Holt (eds.). Great Events in Religion: An Encyclopedia of Pivotal Events in Religious History. ABC-CLIO, 2016. ISBN 978-1610695657

- Dark, Ken, and Jan Kostenec. Hagia Sophia in Context: An Archaeological Re-examination of the Cathedral of Byzantine Constantinople. Oxbow Books, 2023. ISBN 978-1789259872

- Fazio, Michael, Marian Moffett, and Lawrence Wodehouse. Buildings Across Time: An Introduction to World Architecture. McGraw Hill, 2022. ISBN 978-1265219499

- Janin, Raymond. Les Eglises Et Les Monasteres: La Geographie Ecclesiastique de L'Empire Byzantin. Peeters, 1969. ISBN 978-9042931206

- Kleiner, Fred S. Gardner's Art Through the Ages: A Global History, Volume I. Cengage Learning, 2019. ISBN 978-1337696593

- Krautheimer, Richard. Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture. Yale University Press, 1984. ISBN 978-0300052947

- Mainstone, Rowland J. Hagia Sophia: Architecture, Structure and Liturgy of Justinian's Great Church. Thames & Hudson, 1988. ISBN 978-0500340981

- Mamboury, Ernest. The Tourists' Istanbul. Cituri Biraderler Basimevi, 1953. ASIN B001QADUDM

- Mango, Cyril. Byzantine Architecture. Electa / Rizzoli, 1985. ISBN 978-0847806157

- Melton, J. Gordon, and Martin Baumann (eds.). Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices. ABC-CLIO, 2002. ISBN 978-1576072233

- Meyendorff, John. The Byzantine Legacy in the Orthodox Church. Yonkers: St Vladimir's Seminary Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0913836903

- M├╝ller-Wiener, Wolfgang. Bildlexikon zur Topographie Istanbuls. Wasmuth, 1977. ISBN 978-3803010223

- Opstall, Emilie M. van. Sacred Thresholds: The Door to the Sanctuary in Late Antiquity. Brill, 2018. ISBN 9004368590

- Parry, Ken. The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. Wiley-Blackwell, 2010. ISBN 978-1444333619

- Patricios, Nicholas N. The Sacred Architecture of Byzantium: Art, Liturgy and Symbolism in Early Christian Churches. I.B.Tauris, 2013. ISBN 978-1780762913

- Rybczynski, Witold. The Story of Architecture. Yale University Press, 2022. ISBN 978-0300246063

- Sahin, Mustafa (ed.). 11th International Colloquium on Ancient Mosaics, October 16th-20th, 2009, Bursa, Turkey: Mosaics of Turkey and Parallel Developments in the Rest of the Ancient and Medieval World. Ege Yayinlari, 2012. ISBN 978-6055607814

- Schibille, Nadine. Hagia Sophia and the Byzantine Aesthetic Experience. Routledge, 2020. ISBN 978-0367600358

- Teteriatnikov, Natalia B. Mosaics of Hagia Sophia, Istanbul: The Fossati restoration and the work of the Byzantine Institute . Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1998. ISBN 978-0884022640

External links

All links retrieved June 13, 2024

- 360 Degree Virtual Tour of Hagia Sophia Mosque Museum

- The Most Visited Museums of Turkey: Hagia Sophia Museum Governorship of Istanbul

- The Hagia Sophia Grand Mosque M├╝ze ─░stanbul

- Hagia Sophia Istanbul HagiaSophia.com

- Hagia Sophia, 532ÔÇô37 by Emma Wegner, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004.

- Hagia Sophia History.com.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.