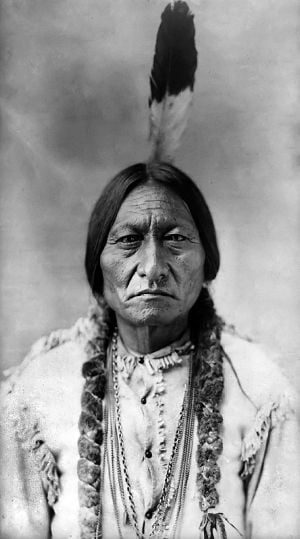

Sitting Bull

Sitting Bull (Sioux: Tatanka Iyotake or Tatanka Iyotanka or Ta-Tanka I-Yotank, first called Slon-he, Slow), (c. 1831 ‚Äď December 15, 1890) was a Hunkpapa Lakota chief and holy man. He is notable in American and Native American history in large part for his major victory at the Battle of Little Bighorn against Custer‚Äôs 7th Cavalry, where his premonition of defeating them became reality. Even today, his name is synonymous with Native American culture, and he is considered one of the most famous Native Americans in history. Towards the end of his life, Sitting Bull accepted that the new society of Europeans in the Americas was there to stay and realized that cooperation was better than confrontation. He was known among the Lakota and even among his adversaries as an inspirational leader and man of principle, whose deep religious faith motivated his life and gave him prophetic insight.

Early life

Sitting Bull was born around 1831 near the Grand River in present-day South Dakota. The Lakota called his birthplace "Many Caches" because it was used for food storage pits to ensure the tribe's survival throughout winter. He was given the birth name Tatanka-Iyotanka (Sioux language: ThathńÖŐĀka √ćyotaka, literally, "buffalo-bull sit-down"), which translates to Sitting Bull. His father's name was Brave Bull because he would always come back with weapons, food, and horses. [1] Early on he was known in his tribe for his excellent singing voice.

Sitting Bull's first encounter with American soldiers occurred in June 1863, when the army mounted a broad campaign in retaliation for the Santee Rebellion in Minnesota, in which the Lakota had played no part. The following year, his tribe clashed with U.S. troops at the Battle of Killdeer Mountain. The battle was a decisive victory for the Army and left the Sioux badly beaten, largely because of the Army artillery's devastating effects.

Tribal Leader

The Battle of Killdeer Mountain struck a significant blow against Native American resistance, and many chiefs gave up the fight and went to reservations. Sitting Bull refused to surrender and rose to be a tribal leader, leading his warriors in a siege against the newly constructed Fort Rice in present day North Dakota. This action won him respect among the tribe, and he became head chief of the Lakota nation around 1868. During this period of westward expansion brought growing numbers of settlers, miners, farmers, missionaries, railroad workers, and military personnel, and Native Americans were increasingly being forced from their tribal lands.

Sitting Bull, who was a medicine man, began to work toward uniting his people against this invasion. Like many tribal leaders, Sitting Bull first attempted to make peace and trade with the whites. However, many of the men the Lakota encountered would trick them into accepting poor deals for their lands and produce, which created resentment among the tribes. After the discovery of gold in 1876 in the Black Hills, his people were driven from their reservation in the area, a place that the Sioux considered holy. Sitting Bull then took up arms against the Americans and refused to be transported to the Indian territory.

Victory at Little Big Horn and the aftermath

Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer, a decorated Union veteran of the Civil War, was an ambitious military officer with presidential hopes. In addition to his Civil War exploits, which included commands in several of the war's most famous battles such as Gettysburg, his presence at Lee's surrender at Appomattox (during which he was awarded the actual table upon which the surrender documents had been signed in recognition of his gallantry) and a notable incident during the Union's Grand Review of the Armies had made Custer a household name by the time he joined the Indian Wars. He earned considerable fame among Native Americans and his fame among whites grew ever larger as the result of a series of controversial battles and early dawn attacks against Indian camps. The battles' results, usually reported to readers on the East Coast as great victories, sometimes included the slaughter of many women and children.

On June 25, 1876, Custer’s 7th Cavalry advance party of General Alfred Howe Terry’s column attacked Indian tribes at their camp on the Little Big Horn River, expecting a similar victory. The U.S. army did not realize that before the battle began, more than 3,000 Native Americans had left their reservations to follow Sitting Bull. The attacking Sioux, inspired by a vision of Sitting Bull’s, in which he saw U.S. soldiers being killed as they entered the tribe’s camp, fought back.

Custer's badly-outnumbered troops lost ground quickly and were forced to retreat as they began to realize the true numbers of the Native American force. Custer also had older and lower quality guns than his enemy, yet he was eager to move into action against the Native Americans, and his hastiness cost him dearly.[2] The tribes then led a counter-attack against the soldiers on a nearby ridge, ultimately annihilating the soldiers.

The victory placed Sitting Bull among the great Native American leaders such as fellow Little Bighorn veteran Crazy Horse and Apache freedom fighter Geronimo. But the Native Americans' celebrations were short lived, as public outrage at the military catastrophe, Custer's death, and heightened wariness of the remaining Native Americans brought thousands more cavalrymen to the area. The country was appalled at the mutilations of soldiers' bodies that occurred after the battle, and soon Congress provided the support to push forward its plans for Indian removal.[3] Over the next year, the new forces relentlessly pursued the Lakota, forcing many of the Indians to surrender. Sitting Bull refused to surrender, and in May 1877 led his band across the border into Canada, where he remained in exile for many years, refusing a pardon and the chance to return.

Surrender

Hunger and cold eventually forced Sitting Bull, his family, and a few remaining warriors to surrender on July 19, 1881. Sitting Bull had his son hand his rifle to the commanding officer of Fort Buford, telling the soldiers they had come to regard them and the white race as friends.

He hoped to return to the Standing Rock Agency reservation but was imprisoned for two years by the army, which was fearful of Sitting Bull's influence and notoriety among his own people and, increasingly, among whites in the East, especially in Boston and New York. He was eventually allowed to return to the reservation and his own people.[4]

Fame

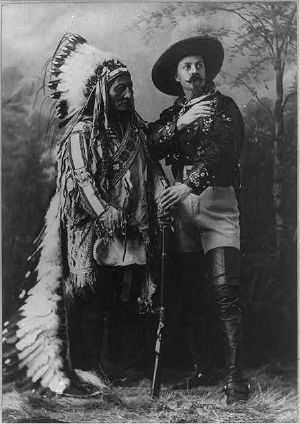

In 1885, Sitting Bull was allowed to leave the reservation to join Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West show. He was rumored to earn about US$50 a week for riding once around the arena, where he was a popular attraction. Often asked to address the audience, he frequently cursed them in his native tongue to the wild applause of his listeners. Sitting Bull only stayed with the show for four months before returning home. During that time, he had become somewhat of a celebrity and a romanticized freedom fighter. He earned a small fortune by charging for his autograph and picture.

In his trips throughout the country, Sitting Bull realized that his former enemies were not limited to the small military and settler communities he had encountered in his homelands, but were in fact a large and highly advanced society. He understood that the Native Americans would be overwhelmed if they continued to fight.

Death

Back at Standing Rock, Sitting Bull became interested in the Ghost Dance movement. Although it has never been proven that he joined, he allowed others in the tribe to do so. The movement's followers believed performing the ghost dance would make them impervious to the bullets fired by white soldiers. The authorities feared Sitting Bull, as a popular spiritual leader, would give more credibility to the movement and decided to arrest him. Pre-empting the army, 43 Indian police attempted to arrest him on December 15, 1890, at the Standing Rock Agency. However, his followers were still loyal and fought to prevent the arrest, fearing that the army meant to kill Sitting Bull. Shots were fired and Sitting Bull, who was hit in the head, and his son Crow Foot were both killed.

Sitting Bull's body was taken by the Indian police to Fort Yates, North Dakota, and buried in the military cemetery. The Lakota claim that his remains were transported in 1953 to Mobridge, South Dakota, where a granite shaft marks his grave. Sitting Bull is still remembered among the Lakota not only as an inspirational leader and fearless warrior, but as a loving father, a gifted singer, and as a man always affable and friendly toward others, whose deep religious faith gave him prophetic insight and lent special power to his prayers.

Following his death, his cabin on the Grand River was taken to Chicago to become part of the 1893 Columbian Exhibition.

Legacy

Sitting Bull, for many, is a symbol of Native American culture. Despite his reputation as a warrior, he was remembered by his friend, Inspector James Morrow Walsh of the North-West Mounted Police, as wanting only justice: "He asked for nothing but justice ‚Ķ he was not a cruel man, he was kind of heart; he was not dishonest, he was truthful.‚ÄĚ [5]

Despite the dispossession of the Indians from their land, Sitting Bull, towards the end of his life, accepted that the new society of Europeans in the Americas was there to stay. He realized that cooperation was better than confrontation and upheld his personal dignity and the dignity of Native Americans in his people's encounter with superior force.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ William Bright, Native American Place Names of the United States (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004, ISBN 9780806135762), 449.

- ‚ÜĎ William M. Osborn, The Wild Frontier: Atrocities During the American-Indian War From Jamestown Colony to Wounded Knee (New York: Random House, 2000, ISBN 9780375503740), 231.

- ‚ÜĎ Osborn, 229.

- ‚ÜĎ Osborn, 263-267.

- ‚ÜĎ J. W. Grant MacEwan, TA-TANKA I-YOTANK (Ta-tanka Yotanka, Sitting Bull Canadian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bright, William. Native American Place Names of the United States. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004. ISBN 9780806135762

- Brown, Dee. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. NY: Henry Holt and Company, 2001. ISBN 0805066691

- DeWall, Robb. The Saga of Sitting Bull's Bones: The Unusual Story Behind Sculptor Korczak Ziolkowski's Memorial to Chief Sitting Bull. Crazy Horse: Korczak's Heritage, 1984. ISBN 978-9995323523

- Newson, T. M. Thrilling scenes among the Indians. With a graphic description of Custer's last fight with Sitting Bull. Forgotten Books, 2017 (original 1884). ISBN 978-1331792376

- Osborn, William M. The Wild Frontier: Atrocities During the American-Indian War From Jamestown Colony to Wounded Knee. New York: Random House, 2000. ISBN 9780375503740

- Reno, Marcus A. Reno Court of Inquiry: Official record, court of inquiry to investigate the conduct of Major Marcus A. Reno, 7th U.S. Cavalry, at the battle of the Little Big Horn River, Montana, June 25-26, 1876. Costa Mesa, CA: R.H. Nichols, 1983.

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who In The Civil War. New York: New York Facts on File Publishing, 1988. ISBN 9780816010554

- Urwin, Gregory J. W. Custer Victorious: The Civil War Battles of General George Armstrong Custer. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0785807483

- Utley, Robert M. The Lance and the Shield: The Life and Times of Sitting Bull. New York: Henry Holt and Company Inc., 1993. ISBN 9780805012743

External links

All links retrieved January 29, 2023.

- Tatanka Iyotaka Biography by Stanley L. Klos

- Ta-tanka Yotanka, Sitting Bull Dictionary of Canadian Biography

- Biography: Sitting Bull PBS American Experience

- Sitting Bull killed by Indian police History.com

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.