Tlingit

| Tlingit |

|---|

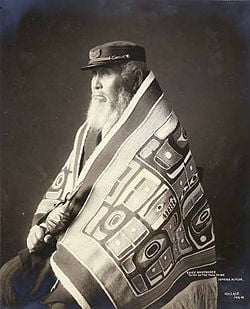

Chief Anotklosh of the Taku Tribe, ca. 1913 |

| Total population |

| 15,000-20,000 |

| Regions with significant populations |

| USA (Alaska), Canada (British Columbia, Yukon) |

| Languages |

| English, Tlingit |

| Religions |

| Christianity, other |

The Tlingit (IPA: /'klɪŋkɪt/, also /-gɪt/ or /'tlɪŋkɪt/ which is often considered inaccurate) are an Indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest. Their name for themselves is Lingít (/ɬɪŋkɪt/), meaning "people." The Russian name Koloshi (from an Aleut term for the labret) or the related German name Koulischen may be encountered in older historical literature.

The Tlingit are a matrilineal society who developed a complex hunter-gatherer culture in the temperate rainforest of the southeast Alaska coast and the Alexander Archipelago. The Tlingit language is well known not only for its complex grammar and sound system but also for using certain phonemes which are not heard in almost any other language. Like other Northwest Coast peoples, the Tlingit carve totem poles and hold potlatches.

Contemporary Tlingit continue to live in areas spread across Alaska and Canada. They are not restricted to reservations, but, together with the Haida, are united in the Central Council of the Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska. After facing struggles to preserve their identity, land, traditional way of life, Tlingit have been able to rebuild their lives and increasingly practice the traditional crafts as well as fishing, which has always been the basis of their economy.

Territory

The maximum territory historically occupied by the Tlingit extended from the Portland Canal along the present border between Alaska and British Columbia north to the coast just southeast of the Copper River delta. The Tlingit occupied almost all of the Alexander Archipelago except the southernmost end of Prince of Wales Island and its surroundings into which the Kaigani Haida moved just before the first encounters with European explorers. Inland, the Tlingit occupied areas along the major rivers which pierce the Coast Mountains and Saint Elias Mountains and flow into the Pacific, including the Alsek, Tatshenshini, Chilkat, Taku, and Stikine rivers. With regular travel up these rivers the Tlingit developed extensive trade networks with Athabascan tribes of the interior, and commonly intermarried with them. From this regular travel and trade, a few relatively large populations of Tlingit settled around the Atlin, Teslin, and Tagish lakes, the headwaters of which flow from areas near the headwaters of the Taku River.

History

The traditional history of the Tlingit involves the creation stories, the Raven Cycle, other tangentially related events during the mythic age when spirits freely transformed from animal to human and back, the migration story of coming to Tlingit lands, the clan histories, and more recent events near the time of first contact with Europeans. At this point the European and American historical records come into play, and although modern Tlingits have access to and review these historical records, they continue to maintain their own historical record by telling stories of ancestors and events which have importance to them against the background of the changing world.

The Tlingit migration

There are several variations of the Tlingit story of how they came to inhabit their lands. They vary mostly in location of the events, with some being very specific about particular rivers and glaciers, others being more vague. There are also variations in the relationship between the Tlingit and their inland neighbors, the Athabaskans.

One version of the Tlingit migration story begins with the Athabaskan (Ghunanaa) people of interior Alaska and western Canada, a land of lakes and rivers, of birch and spruce forests, and the moose and caribou. Life in this continental climate is harsh, with bitterly cold winters and hot summers. One year the people had a particularly poor harvest over a summer, and it was obvious that the winter would bring with it many deaths from starvation. The elders gathered together and decided that people would be sent out to find a land which was rumored to be rich in food, a place where one did not even have to hunt for something to eat. A group of people were selected and sent out to find this new place, and would come back to tell the elders where this land could be found. They were never heard from again. These people were the Navajo and Apache, for they left the Athabaskan lands for a different place far south of their home, and yet retain a close relationship with their Athabaskan ancestors.

Over the winter countless people died. Again, the next summer's harvest was poor, and the life of the people was threatened. So once again, the elders decided to send out people to find this land of abundance. These people traveled a long distance, and climbed up mountain passes to encounter a great glacier. The glacier seemed impassable, and the mountains around it far too steep for the people to cross. They could however see how the meltwater of the glacier traveled down into deep crevasses and disappeared underneath the icy bulk. The people to follow this river to see if it came out on the other side of the mountains, and an elderly couple volunteered to make the trip. They made a simple dugout canoe and took it down the river under the glacier, and came out to see a rocky plain with deep forests and rich beaches all around. The people followed them down under the glacier and came into Lingít Aaní, the rich and bountiful land that became the home of the Tlingit people. These people became the first Tlingits.

Another version suggests the Tlingit people crossed into Alaska by way of the Bering land bridge. Coastal people in general are extremely aggressive; whereas interior Athabascan people are more passive. Tlingit culture, being the fiercest among the coastal nations due to their northernmost occupation, began to dominate the interior culture as they traveled inland to secure trading alliances. Tlingit traders were the "middlemen" bringing Russian goods inland over the Chilkoot Trail to the Yukon, and on into Northern British Columbia. As the Tlingit people began marrying interior people, their culture became the established "norm." Soon the Tlingit clan and political structure, as well as customs and beliefs dominated all other interior culture. To this day, Tlingit regalia, language, clan structure, political structure, and ceremonies including beliefs are evident in all interior culture.

Clan histories

The clans were Yehi, or Raven; Goch, or Wolf; and Nehadi, or Eagle. Each clan in Tlingit society has its own foundation history which describes the Tlingit world from a different perspective, and taken together the clan histories recount much of the history of the Tlingits before the coming of the Dléit Khaa, the white people.

Typically a clan history involves some extraordinary event that happened to some family or group of families which brought them together and at once separated them from other Tlingits. Some clans seem to be older than others, and often this is notable by their clan histories having mostly mythic proportions. Younger clans seem to have histories that tell of breaking apart from other groups due to internal conflict and strife or the desire to find new territory.

First contact

A number of both well-known and undistinguished European explorers investigated Lingít Aaní and encountered the Tlingit in the earliest days of contact. The earliest expedition, led by Juan Josef Pérez Hernández of Spain, had cordial experiences with the Tlingit and drawings made by one of his men today serve as invaluable records of Tlingit life in the precolonial period. Another Spanish expedition, led by Alessandro Malaspina, made contact with the Tlingit at Yakutat Bay in 1791. Spanish scholars made a study of the tribe, recording information on social mores, language, economy, warfare methods, and burial practices. These Spanish expeditions had been instructed by the viceroy of New Spain, Bucareli, to act in a peaceful manner, to study and trade with the native people and treat them with respect, and to chart the waters in preparation for establishing settlements.

Most of these early exchanges were congenial. The Tlingit rather quickly appreciated the trading potential for valuable European goods and resources, and exploited this whenever possible in their early contacts. On the whole the European explorers were impressed with Tlingit wealth, but put off by what they felt was an excessive lack of hygiene. Considering that most of the explorers visited during the busy summer months when Tlingit lived in temporary camps, this impression is unsurprising. In contrast, the few explorers who were forced to spend time with the Tlingit tribe during the inclement winters made mention of the cleanliness of Tlingit winter homes and villages.

However, relations between Tlingit and Russian settlers in the early 1800s became strained and hostilities erupted.

Battle of Sitka

The Battle of Sitka (1804) was a major armed conflict between Europeans and the Tlingit, and was initiated in response to the destruction of a Russian trading post two years prior. Though the Russians' initial assault (in which Alexandr Baranov, head of the Russian expedition, sustained serious injuries) was repelled, their naval escorts bombarded the Tlingit fort Shis'kí Noow mercilessly, driving the natives into the surrounding forest after only a few days. The Russian victory was decisive, and resulted in the Tlingit being permanently displaced from their ancestral lands. The Tlingit fled north and established a new settlement on the neighboring Chichagof Island. Animosity between the two cultures, though greatly diminished, continued in the form of sporadic attacks by the natives against the Russian settlement as late as 1858.

U.S. President Benjamin Harrison set aside the Shis'kí Noow site for public use in 1890. Sitka National Historical Park was established on the battle site on October 18, 1972 "to commemorate the Tlingit and Russian experiences in Alaska." Today, the K'alyaan (Totem) Pole stands guard over the Shis'kí Noow site to honor the Tlingit casualties. Ta Éetl, a memorial to the Russian sailors who died in the battle, is located across the Indian River at site of the Russians' landing. In September, 2004, in observance of the Battle's bicentennial, descendants of the combatants from both sides joined in a traditional Tlingit "Cry Ceremony" to formally grieve their lost ancestors. The next day, the Kiks.ádi hosted a formal reconciliation ceremony to "put away" their two centuries of grief.

Culture

The Tlingit culture is multifaceted and complex, a characteristic of Northwest Pacific Coast peoples with access to easily exploited rich resources. In Tlingit culture a heavy emphasis is placed upon family and kinship, and on a rich tradition of oratory. Wealth and economic power are important indicators of status, but so is generosity and proper behavior, all signs of "good breeding" and ties to aristocracy. Art and spirituality are incorporated in nearly all areas of Tlingit culture, with even everyday objects such as spoons and storage boxes decorated and imbued with spiritual power and historical associations.

Social structure

The Tlingit kinship system, like most Northwest Coast societies, is based on a matrilineal structure, and describes a family roughly according to Lewis Henry Morgan's Crow system of kinship. The society is wholly divided into two distinct moieties, termed Raven (Yéil) and Eagle/Wolf (Ch'aak'/Ghooch). The former identifies with the raven as its primary crest, but the latter is variously identified with the wolf, the eagle, or some other dominant animal crest depending on location; occasionally this moiety is simply called the "not Raven" people. Members of one moiety traditionally may only marry a person of the opposite moiety, however in the last century this system began to break down and today so-called "double-eagle" and "double-raven" marriages are common, as well as marriages with non-Tlingit people.

The moieties provide the primary dividing line across Tlingit society, but identification is rarely made with the moiety. Instead individuals identify with their matrilineal clan (naa), a large group of people related by shared genealogy, history, and possessory rights. Clan sizes vary widely, and some clans are found throughout all the Tlingit lands whereas others are found only in one small cluster of villages. The Tlingit clan functions as the main property owner in the culture, thus almost all formal property amongst the Tlingit belongs to clans, not to individuals.

Because of the heavy emphasis on clan and matrilineality the father played a relatively minor role in the lives of his children. Instead, what Europeans would consider the father's primary role was filled by the mother's brother, the children's maternal uncle, who was of the same clan as the children. This man would be the caretaker and teacher of the children, as well as the disciplinarian. The father had a more peripheral relationship with the children, and as such many Tlingit children have very pleasant memories of their fathers as generous and playful, while they maintain a distinct fear and awe of their maternal uncles who exposed them to hard training and discipline.

Beneath the clans are houses (hít), smaller groups of people closely related by family, and who in earlier times lived together in the same large communal house. The physical house itself would be first and foremost property of the clan, but the householders would be keepers of the house and all the material and non-material goods associated with it. Each house was led by a "chief," in Tlingit hít s'aatí "house master," an elder male (or less often a female) of high stature within the family. Hít s'aatí who were recognized as being of particularly high stature in the community, to the point of being major community leaders, were called aan s'aatí or more often aankháawu, "village master" or "village leader." The term aan s'aatí is now used to refer to an elected city mayor in Tlingit, although the traditional position was not elected and did not imply some coercive authority over the residents.

The existence of a "chief" for every house lineage in a village confused many early European explorers and traders who expected a single autocratic "chief" in a given village or region. This led to numerous confrontations and skirmishes among the Europeans and Tlingit in early history, since a particular "chief" could only hold sway over members of his own household and not over others in the village. A high stature hít s'aatí could convince unrelated villagers to behave a certain way, but if he lost significant status the community would begin to ignore him, much to the dismay of Europeans who were depending on his authority.

Historically, marriages amongst Tlingits and occasionally between Tlingits and other tribes were arranged. The man would move into the woman's house and become a member of that household, where he would contribute towards communal food gathering and would have access to his wife's clan's resources. Because the children would be of the mother's clan, marriages were often arranged such that the man would marry a woman who was of the same clan as his own father, though not a close relation. This constituted an ideal marriage in traditional Tlingit society, where the children were of the same clan as their paternal grandfather and could thus inherit his wealth, prestige, names, occupation, and personal possessions.

The opposition of clans is also a motivator for the reciprocal payments and services provided through potlatches. Indeed, the institution of the potlatch is largely founded on the reciprocal relationship between clans and their support during mortuary rituals. When a respected Tlingit dies the clan of his father is sought out to care for the body and manage the funeral. His own clan is incapable of these tasks due to grief and spiritual pollution. The subsequent potlatches are occasions where the clan honors its ancestors and compensates the opposite clans for their assistance and support during trying times. This reciprocal relationship between two clans is vital for the emotional, economic, and spiritual health of a Tlingit community.

Property and place

Property and place are both very important in Tlingit culture. Place signifies not just a specific geographical location but is also an integral part of the ways in which individuals and social groups define themselves. Place has three dimensions—space, time, and experience—which are culturally and environmentally structured. Geographic references are embedded in personal names, clan names, and house names. Tribe names define regions of dwelling; for example, the Sheet'ka K-waan (Sitka tribe) is the Tlingit community that inhabits Sheet'ka (Sitka).

In Tlingit society many things are considered property which are not in European societies. This includes names, stories, speeches, songs, dances, landscape features (such as mountains), and artistic designs. Some of these notions of property are similar to those considered under modern intellectual property law. More familiar property objects are buildings, rivers, totem poles, berry patches, canoes, and works of art.

A myriad of art forms are considered property in Tlingit culture. In Tlingit culture, the ideas behind artistic designs are themselves property, and their representation in art by someone who cannot prove ownership is an infringement upon the property rights of the proprietor.

Stories, songs, and dances are generally considered property of particular clans. Certain stories are, however, essentially felt to be in the public domain, such as many of the humorous tales in the Raven cycle. A number of children's songs or songs sung to children, commonly called 'lullabies', are considered to be in the public domain. Since people from different clans are often involved in the performance of a dance, it is considered essential that before the dance is performed or the song sung that a disclaimer be made regarding who permission was obtained from, and with whom the original authorship or ownership rests.

Before 1867 the Tlingit were avid practitioners of slavery. The outward wealth of a person or family was roughly calculated by the number of slaves held. Slaves were taken from all peoples that the Tlingit encountered, from the Aleuts in the west, the Athabascan tribes of the interior, and all of the many tribes along the Pacific coast as far south as California. Slaves were bought and sold in a barter economy along the same lines as any other trade goods. They were often ceremonially freed at potlatches, the giving of freedom to the slave being a gift from the potlatch holder. However, they were just as often ceremonially killed at potlatches as well, to demonstrate economic power or to provide slaves for dead relatives in the afterlife.

Since slavery was an important economic activity to the Tlingit, it came as a tremendous blow to the society when emancipation was enforced in Alaska after its purchase by the United States from Russia in 1867. This forced removal of slaves from the culture caused many Tlingit to become incensed when they were not repaid for their loss of property. In a move traditional against those with unpaid debts, a totem pole was erected that would shame the Americans for not having paid back the Tlingits for their loss, and at its top for all to see was a very carefully executed carving of Abraham Lincoln, whom the Tlingits were told was the person responsible for freeing the slaves.

Potlatch

Potlatches were held for deaths, births, naming, marriages, sharing of wealth, raising totem poles, special events, and honoring the leaders or the departed.

The memorial potlatch is a major feature of Tlingit culture. A year or two following a person's death this potlatch was held to restore the balance of the community. Members of the deceased family were allowed to stop mourning. If the deceased was an important member of the community, like a chief or a shaman for example, at the memorial potlatch his successor would be chosen. Clan members from the opposite moiety took part in the ritual by receiving gifts and hearing and performing songs and stories. The function of the memorial potlatch was to remove the fear from death and the uncertainty of the afterlife.

Art

The Tlingit are famous for their carved totem poles made of cedar trees. Their culture is largely based on reverence towards the Native American totem animals, and the finely detailed craftsmanship of woodworking depicts their spirituality through art. Traditional colors for the decorative art of the Tlingit are generally greens, blues, and reds, which can make their works easily recognizable to the lay person. Spirits and creatures from the natural world were often believed to be one and the same, and were uniquely depicted with varying degrees of realism. The Tlingit use stone axes, drills, adzes, and different carving knives to craft their works, which wae generally made out wood, although precious metals such as silver and copper are not uncommon mediums for Tlingit art, as well as the horns of animals.

Posts in the house which divide the rooms are often ornately carved with family crests, as well as gargoyle-like figures to ward off evil spirits. Great mythology and legend is associated with each individual totem pole, often telling a story about the ancestry of the household, or a spiritual account of a famous hunt.

Food

Food is a central part of Tlingit culture, and the land is an abundant provider. A saying amongst the Tlingit is that "when the tide goes out the table is set." This refers to the richness of intertidal life found on the beaches of Southeast Alaska, most of which can be harvested for food. Another saying is that "in Lingít Aaní you have to be an idiot to starve." However, though eating off the beach would provide a fairly healthy and varied diet, eating nothing but "beach food" is considered contemptible among the Tlingit, and a sign of poverty. Indeed, shamans and their families were required to abstain from all food gathered from the beach, and men might avoid eating beach food before battles or strenuous activities in the belief that it would weaken them spiritually and perhaps physically as well.

The primary staple of the Tlingit diet, salmon was traditionally caught using a variety of methods. The most common being the fishing weir or trap to restrict movement upstream. These traps allowed hunters to easily spear a good amount of fish with little effort. It did, however, required extensive cooperation between the men fishing and the women on the shore doing the cleaning.

Fish traps were constructed in a few ways, depending on the type of river or stream being worked. At the mouth of a smaller stream wooden stakes were driven in rows into the mud in the tidal zone, to support a weir constructed from flexible branches. After the harvest the weir would be removed but the stakes left behind; archaeological evidence has uncovered a number of sites where long rows of sharpened stakes were hammered into the gravel and mud. Traps for smaller streams were made using rocks piled to form long, low walls. These walls would be submerged at high tide and the salmon would swim over them. The remnants of these walls are still visible at the mouths of many streams; although none are in use today elders recall them being used in the early twentieth century. Fishwheels, though not traditional, came into use in the late nineteenth century.

None of the traditional means of trapping salmon had a severe impact on the salmon population, and once enough fish were harvested in a certain area the people would move on to other locations, leaving the remaining run to spawn and guarantee future harvests.

Salmon are roasted fresh over a fire, frozen, or dried and smoked for preservation. All species of salmon are harvested, and the Tlingit language clearly differentiates them. Smoking is done over alder wood either in small modern smoke houses near the family's dwelling or in larger ones at the harvesting sites maintained by particular families. Once fully cured the fish are cut into strips and are ready to eat or store. Traditionally they were stored in bentwood boxes filled with seal oil, which protected the fish from mold and bacteria.

During the summer harvesting season most people would live within their smokehouses, transporting the walls and floors from their winter houses to their summer locations where the frame for the house stood. Besides living in smokehouses, other summer residences were little more than hovels built from blankets and bark set up near the smokehouse. In the years following the introduction of European trade, canvas tents with woodstoves came into fashion. Since this was merely a temporary location, and since the primary purpose of the residence was not for living but for smoking fish, the Tlingit cared little for the summer house's habitability, as noted by early European explorers, and in stark contrast to the remarkable cleanliness maintained in winter houses.

Herring (Clupea pallasii) and hooligan (Thaleichthys pacificus) both provide important foods in the Tlingit diet. Herring are traditionally harvested with herring rakes, long poles with spikes which are swirled around in the schooling fish. Herring eggs are also harvested, and are considered a delicacy, sometimes called "Tlingit caviar." Either ribbon kelp or (preferably) hemlock branches are submerged in an area where herring are known to spawn, and are marked with a buoy. Once enough eggs are deposited the herring are released from the pen to spawn further, thus ensuring future harvests.

Hooligan are harvested by similar means as herring, however they are valued more for their oil than for their flesh. Instead of smoking, they are usually tried for their oil by boiling and mashing in large cauldrons or drums (traditionally old canoes and hot rocks were used), the oil skimmed off the surface with spoons and then strained and stored in bentwood boxes. Hooligan oil was a valuable trade commodity which enriched khwáan such as the Chilkat who saw regular hooligan runs every year in their territory.

Unlike almost all other north Pacific coast peoples, the Tlingit do not hunt whale. Various explanations have been offered, but the most common reason given is that since a significant portion of the society relates itself with either the killer whale or other whale species via clan crest and hence as a spiritual member of the family, eating whale would be tantamount to cannibalism. A more practical explanation follows from the tendency of the Tlingit to harvest and eat in moderation despite the surrounding abundance of foodstuffs.

Game forms a sizable component of the traditional Tlingit diet, and the majority of food that is not derived from the sea. Major game animals hunted for food are Sitka deer, rabbit, mountain goat in mountainous regions, black bear and brown bear, beaver, and, on the mainland, moose.

Religion

Tlingit thought and belief, although never formally codified, was historically a fairly well organized philosophical and religious system whose basic axioms shaped the way all Tlingit people viewed and interacted with the world around them. Between 1886-1895, in the face of their shamans' inability to treat Old World diseases including smallpox, most of the Tlingit people converted to Orthodox Christianity. After the introduction of Christianity, the Tlingit belief system began to erode.

Today, some young Tlingits look back towards what their ancestors believed, for inspiration, security, and a sense of identity. This causes some friction in Tlingit society, because most modern Tlingit elders are fervent believers in Christianity, and have transferred or equated many Tlingit concepts with Christian ones.

Dualism

The Tlingit see the world as a system of dichotomies. The most obvious is the division between the light water and the dark forest which surrounds their daily lives in the Tlingit homeland.

Water serves as a primary means of transportation, and as a source of most Tlingit foods. Its surface is flat and broad, and most dangers on the water are readily perceived by the naked eye. Light reflects brightly off the sea, and it is one of the first things that a person in Southeast Alaska sees when they look outside. Like all things, danger lurks beneath its surface, but these dangers are for the most part easily avoided with some caution and planning. For such reasons it is considered a relatively safe and reliable place, and thus represents the apparent forces of the Tlingit world.

In contrast, the dense and forbidding rainforest of Southeast Alaska is dark and misty even in the brightest summer weather. Untold dangers from bears, falling trees, and the risk of being lost all make the forest a constantly dangerous place. Vision in the forest is poor, reliable landmarks are few, and food is scarce in comparison to the seashore. Entering the forest always means traveling uphill, often up the sides of steep mountains, and clear trails are rare to nonexistent. Thus the forest represents the hidden forces in the Tlingit world.

Another series of dichotomies in Tlingit thought are wet versus dry, heat versus cold, and hard versus soft. A wet, cold climate causes people to seek warm, dry shelter. The traditional Tlingit house, with its solid redcedar construction and blazing central fireplace, represented an ideal Tlingit conception of warmth, hardness, and dryness. Contrast the soggy forest floor that is covered with soft rotten trees and moist, squishy moss, both of which make for uncomfortable habitation. Three attributes that Tlingits value in a person are hardness, dryness, and heat. These can be perceived in many different ways, such as the hardness of strong bones or the hardness of a firm will; the heat given off by a healthy living man, or the heat of a passionate feeling; the dryness of clean skin and hair, or the sharp dry scent of cedar.

Spirituality

The Tlingit divide the living being into several components:

- khaa daa—body, physical being, person's outside (cf. aas daayí "tree's bark or outside")

- khaa daadleeyí—the flesh of the body (< daa + dleey "meat, flesh")

- khaa ch'áatwu—skin

- khaa s'aaghí—bones

- xh'aséikw—vital force, breath (< disaa "to breathe")

- khaa toowú—mind, thought and feelings

- khaa yahaayí—soul, shadow

- khaa yakghwahéiyagu—ghost, revenant

- s'igheekháawu—ghost in a cemetery

The physical components are those that have no proper life after death. The skin is viewed as the covering around the insides of the body, which are divided roughly into bones and flesh. The flesh decays quickly, and in most cases has little spiritual value, but the bones form an essential part of the Tlingit spiritual belief system. Bones are the hard and dry remains of something which has died, and thus are the physical reminder of that being after its death. In the case of animals, it is essential that the bones be properly handled and disposed, since mishandling may displease the spirit of the animal and may prevent it from being reincarnated. The reason for the spirit's displeasure is rather obvious, since a salmon who was resurrected without a jaw or tail would certainly refuse to run again in the stream where it had died.

The significant bones in a human body are the backbone and the eight "long bones" of the limbs. The eight long bones are emphasized because that number has spiritual significance in Tlingit culture. The bones of a cremated body must be collected and placed with those of the person's clan ancestors, or else the person's spirit might be disadvantaged or displeased in the afterlife, which could cause repercussions if the ghost decided to haunt people or if the person was reincarnated.

The source of living can be found in xh'aséikw, the essence of life. This bears some resemblance to the Chinese concept of qi as a metaphysical energy without which a thing is not alive; however in Tlingit thought this can be equated to the breath as well.

The feelings and thoughts of a person are encompassed by the khaa toowú. This is a very basic idea in Tlingit culture. When a Tlingit references their mind or feelings, he always discusses this in terms of axh toowú, "my mind." Thus "Axh toowú yanéekw," "I am sad," literally "My mind is pained."

Both xh'aséikw and khaa toowú are mortal, and cease to exist upon the death of a being. However, the khaa yahaayí and khaa yakghwahéiyagu are immortal and persist in various forms after death. The idea of khaa yahaayí is that it is the person's essence, shadow, or reflection. It can even refer to the appearance of a person in a photograph or painting, and is metaphorically used to refer to the behavior or appearance of a person as other than what he is or should be.

Heat, dryness, and hardness are all represented as parts of the Tlingit practice of cremation. The body is burned, removing all water under great heat, and leaving behind only the hard bones. The soul goes on to be near the heat of the great bonfire in the house in the spirit world, unless it is not cremated in which case it is relegated to a place near the door with the cold winds. The hardest part of the spirit, the most physical part, is reincarnated into a clan descendant.

Creation story and the Raven Cycle

There are two different Raven characters which can be identified in the Raven Cycle stories, although they are not always clearly differentiated by most storytellers. One is the creator Raven who is responsible for bringing the world into being and who in sometimes considered to be the same individual as the Owner of Daylight. The other is the childish Raven, always selfish, sly, conniving, and hungry.

The theft of daylight

The most well recognized story of is that of the Theft of Daylight, in which Raven steals the stars, the moon, and the sun from the Old Man. The Old Man is very rich and is the owner of three legendary boxes which contain the stars, the moon, and the sun; Raven wants these for himself (various reasons are given, such as wanting to admire himself in the light, wanting light to find food easily). Raven transforms himself into a hemlock needle and drops into the water cup of the Old Man's daughter while she is out picking berries. She becomes pregnant with him and gives birth to him as a baby boy. The Old Man dotes over his grandson, as is the wont of most Tlingit grandparents. Raven cries incessantly until the Old Man gives him the Box of Stars to pacify him. Raven plays with it for a while, then opens the lid and lets the stars escape through the chimney into the sky. Later Raven begins to cry for the Box of the Moon, and after much fuss the Old Man gives it to him but not before stopping up the chimney. Raven plays with it for a while and then rolls it out the door, where it escapes into the sky. Finally Raven begins crying for the Box of the Sun, and after much fuss finally the Old Man breaks down and gives it to him. Raven knows well that he cannot roll it out the door or toss it up the chimney because he is carefully watched. So he finally waits until everyone is asleep and then changes into his bird form, grasps the sun in his beak and flies up and out the chimney. He takes it to show others who do not believe that he has the sun, so he opens the box to show them and then it flies up into the sky where it has been ever since.

Shamanism

The shaman is called ixht'. He was the healer, and the one who foretold the future. He was called upon to heal the sick, drive out those who practiced witchcraft, and tell the future.

The name of the ixt' and his songs and stories of his visions are the property of the clan he belongs to. He would seek spirit helpers from various animals and after fasting for four days when the animal would 'stand up in front of him' before entering him he would obtain the spirit. The tongue of the animal would be cut out and added to his collection of spirit helpers. This is why he was referred to by some as "the spirit man."

A nephew of a shaman could inherit his position. He would be told how to approach the grave and how to handle the objects. Touching shaman objects was strictly forbidden except to a shaman and his helpers.

All shamans are gone from the Tlingit today and their practices will likely never be revived, although shaman spirit songs are still done in their ceremonies, and their stories re-told at those times.

Contemporary Tlingit

The Central Council of the Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska was established in 1935 to pursue a land suit on behalf of the Tlingit and Haida people. This Central Council evolved out of the struggle to retain a subsistence way of life that required the right to their historical lands. On June 19, 1935, an act of Congress was passed to recognize the Tlingit and Haida people as a single federally recognized tribe.

Delineating the modern territory of the Tlingit is complicated by the fact that they are spread across the border between the United States and Canada, by the lack of designated reservations, other complex legal and political concerns, and a relatively high level of mobility among the population. Despite the legal and political complexities, the territory historically occupied by the Tlingit can be reasonably designated as their modern homeland, and Tlingit people today envision the land from around Yakutat south through the Alaskan Panhandle and including the lakes in the Canadian interior as being Lingít Aaní, the Land of the Tlingit.

The territory occupied by the modern Tlingit people in Alaska is not restricted to particular reservations, unlike most tribes in the contiguous 48 states. This is the result of the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) which established regional corporations throughout Alaska with complex portfolios of land ownership rather than bounded reservations administered by tribal governments. The corporation in the Tlingit region is Sealaska, Inc. which serves the Tlingit as well as the Haida in Alaska. Tlingit people as a whole participate in the commercial economy of Alaska, and as a consequence live in typically American nuclear family households with private ownership of housing and land.

Many Tlingit are involved in the Alaskan commercial salmon fisheries. Alaskan law provides for commercial fishermen to set aside a portion of their commercial salmon catch for subsistence or personal use, and today many families no longer fish extensively but depend on a few relatives in the commercial fishery to provide the bulk of their salmon store. Despite this, subsistence fishing is still widely practiced, particularly during weekend family outings.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ames, Kenneth M., and Herbert D.G Maschner. 1999. Peoples of the Northwest Coast: Their archaeology and prehistory. London: Thames and Hudson, Ltd. ISBN 0500281106

- Benson, Diane E. Tlingit Countries and Their Cultures, 2011. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- Emmons, George Thornton. 1991. The Tlingit Indians. Volume 70 In Anthropological Papers of the American Museum of Natural History, Edited with additions by Frederica De Laguna. New York, NY: American Museum of Natural History. ISBN 0295970081

- Dauenhauer, Nora Marks, and Richard Dauenhauer, ed. 1987. Haa Shuká, Our Ancestors: Tlingit oral narratives. Volume 1 in Classics of Tlingit Oral Literature. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295964952

- Dauenhauer, Nora Marks, and Richard Dauenhauer, ed. 1990. Haa Tuwunáagu Yís, for Healing our Spirit: Tlingit oratory. Volume 2 In Classics of Tlingit Oral Literature. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295968508

- Dauenhauer, Nora Marks. 1994. Haa Kusteeyí, Our Culture: Tlingit life stories. Volume 3 In Classics of Tlingit Oral Literature. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. ISBN 029597401X

- De Laguna, Frederica. 1990. "Tlingit." In W. Suttles, Northwest Coast. 203-228. Handbook of North American Indians, (Vol. 7) (W. C. Sturtevant, General Ed.). Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 978-0160203909

- Dombrowski, Kirk. 2001. Against Culture: Development, Politics and Religion in Indian Alaska. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803266322

- Eliade, Mircea. 1964. Shamanism: Archaic techniques of ecstasy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691017794

- Garfield, Viola E., and Linna A. Forrest. 1961. The Wolf and the Raven: Totem poles of Southeast Alaska. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295739983

- Goldschmidt, Walter R., and Theodore H. Haas. 1998. Haa Aaní, Our Land. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. ISBN 029597639X

- Holm, Bill. 1965. Northwest Coast Indian Art: An analysis of form. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295951028

- Hope, III, Andrew. 1982. Raven's Bones. Sitka, AK: Sitka Community Association. ISBN 0911417001

- Hope, Andrew, and Thomas Thorton. 2000. Will the Time Ever Come? A Tlingit sourcebook. Fairbanks, AK: Alaska Native Knowledge Network. ISBN 1877962341

- Huteson, Pamela Rae. 2000. Legends in Wood, Stories of the Totems. Portland, OR: Greatland Classic Sales. ISBN 1886462518

- Kaiper, Nan. 1978. Tlingit: Their art, culture, and legends. Vancouver, British Columbia: Hancock House Publishers, Ltd. ISBN 0888390106

- Kamenskii, Fr. Anatolii. 1985. Tlingit Indians of Alaska, Translated with additions by Sergei Kan. Volume II in Marvin W. Falk (Ed.), The Rasmuson Library Historical Translations Series. Fairbanks, AK: University of Alaska Press. (Originally published as Indiane Aliaski, Odessa: 1906.) ISBN 0912006188

- Kan, Sergei. 1989. Symbolic Immortality: The Tlingit potlatch of the nineteenth century. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 1560983094

- Krause, Arel. [1885] 1956. The Tlingit Indians, Translated by Erna Gunther. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. (Originally published as Die Tlinkit-Indianer. Jena.) ISBN 0295950757

- McClellan, Catharine. 1953. "The inland Tlingit." In Marian W. Smith. Asia and North America: Transpacific contacts. 47-51. Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology (No. 9). Salt Lake City, UT: Society for American Archaeology. ASIN B000CP4JPA

- Olson, Wallace M. 2002. Through Spanish eyes: The Spanish voyages to Alaska, 1774-1792. Heritage Research. ISBN 978-0965900911

- Salisbury, O.M. 1962. The Customs and Legends of the Thlinget Indians of Alaska. New York, NY: Bonanza Books. ISBN 0517135507

- Swanton, John R. 1909. Tlingit myths and texts. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology: bulletin 39. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Reprinted by Nabu Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1177316040

- Thornton, Thomas F. 2007. Being and Place Among the Tlingit. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0295987491

- Waldman, Carl. 2006. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. New York, NY: Checkmark Books. ISBN 978-0816062744

- Woodford, Riley. 2002. How the Tlingits discovered the Spanish, The Juneau Empire. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

External links

All links retrieved April 30, 2023.

- Sealaska Heritage Institute.

- The Tlingit of the Northwest Coast Carnegie Museum of Natural History

- Alaskan Tlingit and Tsimshian - Essay by Jay Miller

- The Tlingit Nation - Snow Owl

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Tlingit history

- History_of_the_Tlingit history

- Culture_of_the_Tlingit history

- Food_of_the_Tlingit history

- Philosophy_and_religion_of_the_Tlingit history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.